Oppositions have won nine of the last thirteen state elections in Australia. In Victoria, a government has not been re-elected since 2006. But barring some life-changing revelation in coming days, the state election on 24 November looks set to break the pattern.

Opinion polls, bookies and commentators all expect the Andrews Labor government to be comfortably re-elected. The Coalition’s victory under Ted Baillieu in 2010 looks like an aberration: Victoria is a Labor state these days, and it is reverting to type.

It’s a long time since Dick Hamer led the Liberals to their ninth consecutive Victorian victory back in 1979 — in each case winning enough votes to govern alone. Since then, the Liberal–National coalition has won just three out of ten state elections, and has won a majority of Victorian seats at just three of the last thirteen federal elections. Combining them, the Coalition’s election record in Victoria since 1980 is stark: won six, lost seventeen.

This could be its eighteenth loss. Statewide opinion polls taken in late October by the firm formerly known as Galaxy — one as a YouGov Galaxy poll for the Herald Sun, one as a Newspoll for the Australian — both showed a swing to the government, with Labor polling 53 to 54 per cent.

This week YouGov Galaxy has polled four marginal Labor seats for the Herald Sun, and for what it’s worth — as marginal seat polling, even by Galaxy, has proved unreliable — all of them found Labor holding its ground: against the Coalition, against the Greens, and against a maverick independent.

A week out from the election, the online bookies on average are offering $1.20 on a Labor victory, $4.25 on a Coalition one. That implies a 78 per cent probability that Labor will win, and less than a one-in-four chance for the Coalition. And they’re offering the same odds on Labor to win next year’s federal election.

It’s a dramatic shift from a year ago. In the first half of 2017, both Galaxy and ReachTEL published polls showing the Coalition poised to win back Victoria in landslide swings of 5 to 6 per cent. Even last December, Galaxy reported that it was a 50–50 contest. But every poll this year has pointed to a Labor win, and as the year has gone on, the gap has widened.

An opinion poll, of course, is not an election. And the one issue the polls have found to be working in the Coalition’s favour is crime. Victorians prefer the Coalition’s “tough on crime” stance to Labor’s watered-down version of the same.

The dominating event of the campaign has been last Friday’s tragedy in Bourke Street, committed by a deranged Somali Muslim refugee. And it’s no surprise that opposition leader Matthew Guy is making the most of it as a vindication of the Coalition’s “tough on crime” policies.

Guy has seized on an unguarded remark Andrews made after the Lindt Café siege in Sydney in 2015, when he warned that “all of us, as Victorians and indeed Australians, have to accept that violent extremism is part of a contemporary Australia.” Every time Guy has faced the cameras in recent days, he has declared over and over: “I do not, have not and never will accept that violent extremism is part of contemporary Australia… There can be no complacency and no equivocation when it comes to protecting the community.”

The Coalition keeps rolling out new plans to toughen penalties for crime, this week proposing to require suspected terrorists to keep away from the CBD, wear electronic monitoring devices and lose access to communications. The issue has been fanned over the years by the incessant focus of the TV evening news on crimes, and the incendiary reporting by Melbourne’s Herald Sun of crimes committed by African gangs, as if these matter more than the 95 per cent of crimes that are committed by others.

Most of the issues the Liberals and their media ally have focused on have failed to bite: the Skyrail project, which has elevated the Cranbourne–Pakenham railway line through some suburbs; the “red shirts” scandal, in which Labor in 2014 broke the rules by allocating electoral staff to campaigning (it has since repaid their salaries); and so on. But the crime issue has a solid base in reality, even if, as Age columnist John Silvester has argued, the solutions are far more complex than the simple retribution the voters are looking for.

Andrews, by contrast, has stayed in the background since the tragedy, mourning cafe owner Sisto Malaspina, while adopting a kind of dignified silence on the causes. He has got to where he is by focusing on building a lot of much-needed transport infrastructure, and by the good fortune of Victoria’s economic boom. He is sticking with those stories.

Indeed, Labor’s priority now seems to be to say as little as possible. Andrews has refused to meet Guy in a debate on ABC television, where many people would be watching, choosing instead the safety of a debate on Sky, where few will see it. Treasurer Tim Pallas has even refused the traditional debate with his counterpart, Michael O’Brien, on ABC radio. Labor is feeling comfortable, and doesn’t want to rock the boat.

But this election might not be as clear-cut as it seems. In seat after seat that is traditionally safe for one major party or the other, this is the year of the independent uprising.

Encouraged by Victoria’s ridiculously low deposit fee of only $350, independent candidates have put themselves forward for seats all over the state, arguing that their area has been neglected because it’s not a marginal seat. Vote for me, they say, and you will start to get new infrastructure, better-resourced schools and hospitals, and all those other services that go to marginal seats.

For many, it will be a persuasive argument. Fewer voters these days are rusted onto either side. What can we lose, they ask, by voting for an independent, to make the big parties take notice of us?

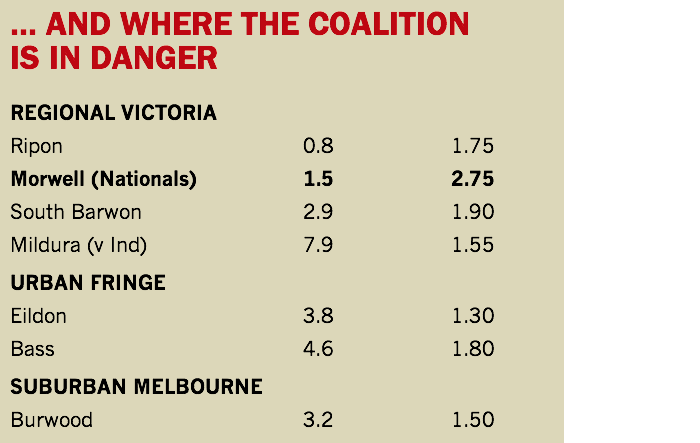

It worked for Suzanna Sheed in 2014, when she took the previously safe seat of Shepparton from the Nationals, after the high dollar almost bankrupted the town’s biggest employer, SPC-Ardmona, and the party’s federal ministers did nothing to help rescue it.

This time, independents are everywhere — and who knows what effect they will have? Every state seat within Cathy McGowan’s federal electorate of Indi has one or two independents standing, most of them running open tickets. In Mildura, where local cop Russell Savage dethroned the sitting National in 1995 in a revolt over the Kennett government’s broken promises, two independents are campaigning hard to unseat the current National MP, Peter Crisp.

In South-West Coast, upper house independent James Purcell is trying to change houses by winning his local seat from the Liberals. A potentially dangerous one for the Nats is Ovens Valley, where Nationals MP Tim McCurdy has been committed to face trial on fraud charges from his earlier life as a real estate agent.

Then there is Morwell, in the heart of the Latrobe Valley, which has been in a generation-long depression since Kennett privatised the previously overstaffed power stations. Local footy legend Russell Northe took the seat from Labor in 2006 for the Nationals, but last year quit the party over claims of financial irregularities due to his gambling addiction. Northe is standing again as an independent. The Liberals and Nationals are both standing. And so is former senator Ricky Muir, this time for the Shooters Party, while Labor too has a strong chance.

But it’s not just a rural phenomenon. While most of the independents standing in Melbourne seats look like ethnic vote harvesters for the Liberals, Pascoe Vale has three independents exchanging preferences to try to unseat Labor MP Lizzie Blandthorn. For now, the bookies think Suzanna Sheed will be the only independent to win, but Northe and a few others are given a decent chance.

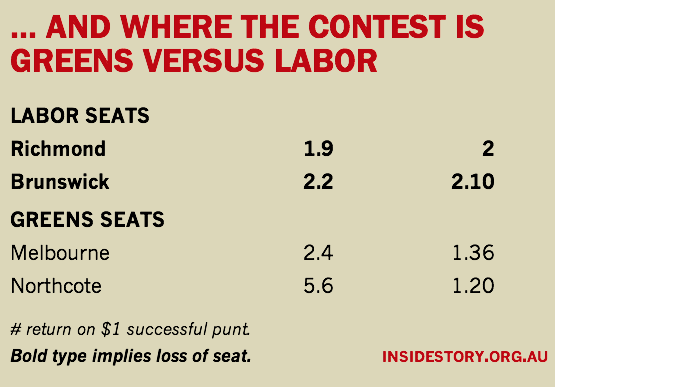

The independents are mostly threats to the Coalition. The threat to Labor is from the Greens.

In 2002, 2006 and 2010, the Greens kept creeping closer to Labor in four inner-city seats — Brunswick, Melbourne, Northcote and Richmond — without breaking through. In 2014, they focused their resources on winning Melbourne from Labor and Prahran from the Liberals, and succeeded in both. Northcote followed at last year’s by-election. This time they hope to hold all three seats, and take Brunswick and Richmond.

That could potentially give them the balance of power in the new eighty-eight-member Assembly. It’s a prospect the Liberals are simultaneously facilitating and warning against. Victoria has not had minority government since 1952, and while Labor and the Greens cohabit amiably in the ACT, it would require a dramatic cultural change in the Victorian Labor branch for it to work successfully there. Expect a barrage of TV ads from the Liberals in the final days about this scary prospect.

But the Liberals are also helping to make it a reality. In 2014 their preferences gave Labor victory in Brunswick, Northcote and Richmond. This time they are not standing in Richmond — the first election since 1952 at which they have left a Labor seat uncontested — to try to ensure that the Greens win it and unseat planning minister Richard Wynne. As of Friday morning, they have still not lodged their final how-to-vote cards for the other seats, but they are expected to be open tickets.

The Greens are tipped to take Brunswick, which former minister Jane Garrett has abandoned to take a seat in the upper house. The bookies have them as narrow favourites in Richmond; but earlier this year Labor retained the federal seat of Batman without Liberal preferences, and it would be no surprise if Wynne hangs on. Richmond, once solidly working-class, now comprises mostly professional/business couples in which both work full-time, giving it the third-highest median household income in Victoria. In the long term, it is a potential Liberal seat.

One Nation has always been weak in Victoria and is not standing this time; nor are Cory Bernardi’s Australian Conservatives. In the lower house, the threat to the major parties is from the independents and the Greens. In the upper house, it is from “preference whisperer” Glenn Druery, who has produced his most complex and wide-ranging set of deals yet, which could send a tsunami of micro-party candidates into the new chamber.

Victoria has eight regions for the Legislative Council, each electing five members — similar to Senate elections, but with four-year terms and the old group voting tickets, in which you just tick the box and the parties decide your preferences in these backroom deals. They’ve been abolished in most other places, with Victoria and Western Australia the last holdouts. And Druery has excelled himself this time.

In 2014 his team won five of the forty seats. Of them, Fiona Patten (Northern Metro) of the Sex Party (now the Reason Party) has made the biggest impact, spearheading Victoria’s controversial dying-with-dignity bill. But Druery’s tickets also elected two MPs from the Shooters Party, a Western District independent who called his party “Vote 1 Local Jobs,” and Rachel Carling-Jenkins, who was elected in Western Metro for the Democratic Labour Party, then joined the Australian Conservatives, then quit them, and is now running as an independent for the Assembly seat of Werribee.

This time Team Druery looks set to win at least one seat in all eight regions, possibly more. We now have eighteen parties standing in every seat, and only the Socialists have refused to take part in these labyrinthine preference swaps. A right-wing “life coach,” Stuart O’Neill, who wants new migrants to be put on a ten-year good behaviour bond and named his team the Aussie Battler Party, looks likely to win a seat in Western Metro on preferences from the Greens, Labor and ten other parties.

Druery now works as chief of staff to senator Derryn Hinch, and he’s set up Hinch’s party nicely in a number of seats, mostly in unobtrusive positions, and it would be no surprise if it wins several seats next Saturday. The Shooters, the Liberal Democrats, a new party called Transport Matters, and possibly even the Dick Smith–backed Sustainable Australia party could win seats under his deals. Fiona Patten, who has fallen out spectacularly with Druery, concedes she now has only a 50–50 chance of holding her seat.

Most of these seats will be taken from Labor, the Coalition and the Greens — who don’t seem to mind, since they made no effort in the last parliament to reform the electoral laws. The Coalition–Greens reform of the Senate voting system provides a model if they ever want to. But in Victoria, Labor was able to work quite well with the crossbenchers in the last parliament and seems to prefer that to putting them out of business.

If the Coalition were to pull off an upset, how could it do it?

First, it could win with less than 50 per cent of the vote. Victoria has seen massive population growth, but mostly in Labor or Greens seats. The average Coalition seat now has 5 per cent fewer voters than the average Labor seat. The differences that have evolved in the six years since the last redistribution — leading to 61,814 voters in Cranbourne versus 38,937 in Mount Waverley — suggest that states growing this fast need a redistribution after every election.

Second, the new socioeconomic geography of Melbourne — higher-income households in the inner and inner-middle suburbs, lower-income households further out — creates electoral opportunities for the Liberals. Census data shows that while the old Liberal heartland (Brighton, Malvern, Kew and Hawthorn) has the greatest concentration of high-income households, Labor and the Greens hold nine of the eighteen seats in the second tier of wealth. And five of them are marginal.

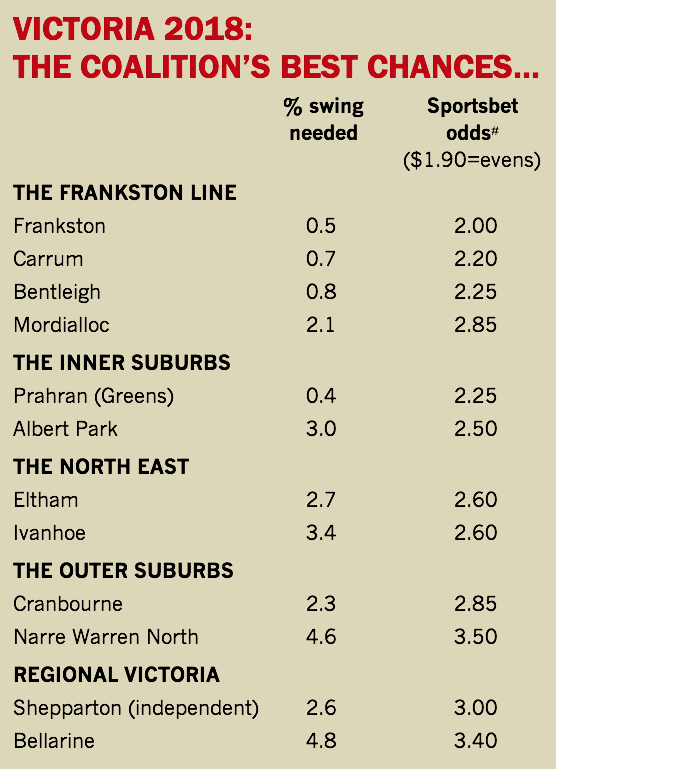

In the inner south, Prahran (Greens, 0.4) became in 2014 the first lower house seat the Greens have ever taken from the Liberals, after narrowly pushing Labor into third place. It’s a three-way contest again this time, and for what it’s worth, the bookies give the Liberals the best chance of the three.

Next-door Albert Park (Labor, 3.0), by contrast, has never been won by the Liberals. But its median household income is now the highest of any Victorian electorate, and when the Liberals eventually get sick of losing and dump the hard right for the political centre, seats like Albert Park and Prahran will form part of the next Liberal majority.

In the northeast, Ivanhoe (Labor, 3.4) has wealthy pockets and poor ones, and is usually held by whoever is in government. Much further out, the same is true of the gumtree-and-mudbrick suburb of Eltham (Labor, 2.7), which has Melbourne’s second-highest concentration of households speaking English only. Chinese buyers don’t go for Eltham style.

The Liberals have hopes in all these four seats. And they will need to win three or four of them to have any hope of forming government.

Third, they need to win back the four seats along the Frankston railway line: in order of distance from Melbourne, Bentleigh (0.8), Mordialloc (2.1), Carrum (0.7), and Frankston (0.5). When they won power in 2010 under Ted Baillieu, the key was that they picked up all four seats, largely on discontent about the poor rail services and road links. But they failed to fix those problems, and in 2014 Labor won back all four seats, and hence government.

The four seats are constantly grouped together, but they are very different. Bentleigh these days is in the second tier of high-wealth electorates by income, and in the top tier for mortgages and rents. It’s full of two-income professional/business families, attracting an ethnic mix of Jewish, Chinese, Greek and Italian voters.

By contrast, Frankston is far more downtrodden. One-in-four households there told the census they lived on less than $650 a week. Its average income is the fourth-lowest of any Melbourne electorate, behind only the three where refugees are concentrated: Broadmeadows, St Albans and Dandenong.

But Frankston has few of them. It’s an old Anglo-Australian mix, the only part of Melbourne with fewer foreign-language speakers than Eltham. But it does have Victoria’s highest divorce rate.

Labor has worked hard to look after these four seats. Level crossings have been removed, a new station has gone up at busy Southland, work is about to start on the Mordialloc Freeway, and it continually announces new services of all kinds. The Liberals have promised their own new freeway, by removing intersections along the Dingley bypass, and thumped the drum about rising crime. For what it’s worth, this week’s YouGov seat polls showed Labor holding Mordialloc and Frankston, with slight swings its way.

The Liberals are hoping that’s wrong. The bookies rate Frankston, Carrum and Bentleigh, along with Prahran and Albert Park, as their best chances of picking up seats anywhere in the state. They need to win most of these to win the election.

On paper, the outer suburbs should provide plenty of prospective gains. In 2014 Labor won the marginal seats of southeastern Cranbourne (2.3 per cent), Narre Warren North (4.6) and Narre Warren South (5.5), as well as the northern fringe seats of Yan Yean (3.7), Macedon (3.8) and Sunbury (4.3), and the Dandenongs electorate of Monbulk (5.0). But only Cranbourne is seen as a frontline seat, and it has many more voters now than in 2014.

It’s a similar story in Geelong, Ballarat and Bendigo. Labor holds seven of their eight seats, mostly by narrow margins. But while the Coalition still hopes to win Bellarine (4.8), the bookies think there is more risk of it losing the one seat it still holds in Victoria’s three main regional centres: the southern Geelong seat of South Barwon (Liberal, 2.9), where the rapidly growing new housing estates are not core Liberal territory.

And in the rest of Victoria, Labor lost its last seat in 2014. It’s the Coalition that is on the defensive against independents (and, in some seats, against Labor).

Overall, a re-elected Labor government is the most likely possibility. But a Labor-led minority government is the next most likely, and one that would require Andrews and his party to climb a steep learning curve. A Coalition-led minority government relying on the independents is an outside chance, a Coalition majority government a very slim one.

And if this election gives Labor an 18–6 winning record in the last twenty-four elections in Victoria, will it lead the Liberals and Nationals to rethink their decision to abandon the political centre for the hard right? Or do its right-wing powerbrokers just want to control their branch, rather than win elections? •