Sandy and Beryl Stone had “a really lovely night’s entertainment” one Tuesday in Melbourne in the late 1950s — according to Barry Humphries’s brilliant “Sandy Stone” satire of Australian suburban life — when they attended a picture night at the tennis club. “The newsreel,” Sandy reported, “had a few shots of some of the poorer type of Italian housing conditions on the Continent and it made Beryl and I realise just how fortunate we were to have the comfort of our own home and all the little amenities round the home that make life easier for the womenfolk, and the menfolk generally, in the home.”

Sandy’s remarks echo those of “Nino Culotta,” the pseudonymous author of John O’Grady’s novel They’re a Weird Mob, which was published at around the time Humphries first performed this sketch. It tells the story of Italian journalist Nino Culotta’s arrival in Sydney and initiation into the Australian way of life. Until a couple of months after the book’s release, Nino was taken by some to be a real migrant. “Italy was a terrible place,” he comments at one point in the story. “Who would want to go back there?’

Sandy and Nino — one very much an “Old” Australian, the other “New” — could agree, as Nino put it, that “there is no better way of life in the world than that of the Australian.” They’re a Weird Mob and its sequels are crude, if sometimes funny, examples of migrant stereotyping and assimilationist propaganda. O’Grady also stacks the cards in favour of Nino’s successful assimilation: apart from making him educated and bourgeois, he has him come from way up north, in Piedmont. Of all Italian regions, Piedmont was the one most readily associated with both political and economic modernity.

By making Nino Piedmontese, O’Grady deliberately confounded his (mainly Anglo-Celtic) readers’ stereotypes of Italians as short, dark and swarthy. “Perhaps it is a matter of opinion,” Nino explains, “and an Australian would lump us all together and call us ‘bloody dagoes,’ but we didn’t like Meridionali [southerners], and they didn’t like us. Up in my country there were a few of them, and mostly they found themselves being officious in the police force. Perhaps subconsciously that is why we did not like them. Nobody likes police forces.”

Published in 1958, the year after O’Grady’s novel, Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend claimed that hostility to the “officiousness and authority” embodied in the police was a distinguishing trait of the typical Australian. Nino was evidently made for us. But O’Grady’s argument works only by creating an “other” against which Nino’s suitability for full acceptance as an Australian can be set: They’re a Weird Mob is unrelenting in its negative portrayal of “Meridionali.”

When Nino finds himself sharing a train carriage with an abusive, racist and drunken “Old” Australian (who naturally assumes that Nino is also an Australian until our hero opens his mouth) and a group of Meridionali, Nino assures the southerners, in Italian, that he will throw the man off the train if he tries to harm them. Interestingly, one of the drunk’s abusive comments towards the southerners is “Knives all bloody over ’em.” How does O’Grady deal with this racist stereotype? By having one of the Meridionali produce a knife. Nino demands the knife and throws it out the window of the train after having “bumped him on the top of his head.”

My family are Meridionali. Although my parents were born in Australia, my four grandparents were from the Aeolian Islands, a group of seven volcanic islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Lipari, my maternal grandparents’ homeland, is the largest; Salina, the original home of my paternal grandparents, is the second largest, and the setting for the film Il Postino (1994), which depicts a stay on the island by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. Stromboli is famous for its lively volcano, while Vulcano, which also has a smouldering crater, is admired for its hot springs and mud baths, if not for its overwhelming smell of sulphur.

The Aeolian Islands have for thousands of years been exploited for their volcanic products, including shiny, black obsidian in ancient times and less striking pumice more recently. They also contain orchards, vineyards, market gardens and farms. At the time of my grandparents’ births, around the turn of the twentieth century, other local men fished or worked in the merchant marine. The grape industry was devastated by phylloxera, the marine by the coming of the railway. A history of rapid outward migration — I also have many relatives in the United States — led to drastic depopulation.

Lipari Island, with Vulcano in the background, c. 1900–10. Alamy

For a time, Mussolini’s fascists used these islands as a conveniently out-of-the-way place to exile political prisoners, but today tourism seems to overwhelm all. The local cult is that of the martyr Bartholomew the Apostle, who was flayed alive. Many in my family have his name; in Australia it has often become Bob, but sometimes Bart.

Odysseus was an early visitor. In his travels he once found himself on “the Aiolian island,” “a floating island, the whole enclosed by a rampart of bronze, not to be broken, and the sheer of the cliff [that] runs upward to it.” There, King Aiolos, a favourite of the gods, lived with his wife and twelve children. Conveniently, these were six sons and six daughters, “so he bestowed his daughters on his sons, to be their consorts.”

Aiolos treated Odysseus and his men with hospitality for a month. When they wanted to leave, the king gave Odysseus a bag containing all the winds, and helpfully set it up so that the west wind would take them home. Ten days after they sailed, they came into sight of home, but a “sweet sleep” came across Odysseus. The men, assuming the bag contained gold and silver, opened it to get their share. The ship was blown back to the island, and an angry Aiolos, assuming those on board were hated by the gods, sent them packing.

The Aeolians have been coming to Australia since the nineteenth century. My father’s family were pre–first world war migrants who settled in the Wimmera town of Nhill. I recently found in the National Library of Australia’s Trove database a Nhill Free Press account of my then-teenage great-aunt Katie — I recall her as an elderly woman in Melbourne in the 1970s — singing at public functions during the first world war. Welcoming two local heroes home from Gallipoli, her “Gondola Dreams” was a nice Italian touch; on another occasion, she was raising funds for the French Red Cross.

The impression left by these fragments of reportage from more than a century ago is of a migrant family doing its best to fit in. But this didn’t mean they left their old associations behind. My father used to joke about a relative who would describe himself as “a dinky-di Aussie, proud to be Italian.”

The Melbourne Aeolian Club (Società Mutuo Soccorso Isole Eolie) was established in 1925, inspired by a migrant who had been a member of a Strombolian club in New York, and the name Bongiorno appears in the minutes of its first meeting, as does Santamaria, the most famous Australian name associated with the island group. The staunchly anti-communist Catholic Bob Santamaria’s family migrated in the same wave as my father’s family, and from the same island, Salina.

As Celeste Russo suggests in her 1986 University of Melbourne thesis on the Aeolian Club, although it brought together “Aeolians,” more local identifications probably mattered most to these people. They identified with their family and village, then with their own island and, at a stretch, with the island group. Sicilians and Calabrians were, by comparison, outsiders. “Bloody Calabrese” were words I sometimes recall hearing in my childhood, a neat combination of Australian vernacular and old enmity.

I gave little thought to my Aeolian ancestry until 1996, when the last of my grandparents died. But that year also provided other reasons to reflect on ethnicity, immigration and identity. This was the time of the Pauline Hanson outbreak, and I was living and working in the southeastern Brisbane suburbs, with their large and prosperous Asian population. Even there, the tensions came to the surface. On one occasion, I was standing in a queue at the Griffith University newsagency while a male customer subjected the young Asian-Australian woman behind the counter to a barrage of verbal abuse. She had made a mildly disparaging remark about Pauline Hanson, who was pictured on the cover of the magazine she was selling him.

Hanson’s arguments against Asian immigration and multiculturalism had been heard loudly and often on the political right, especially since the controversy generated by the historian Geoffrey Blainey in 1984 over the pace of Asian immigration to Australia. Australia, Hanson said, was in danger of being “swamped” by Asians. They did not mix with the existing population; they formed ghettos. Europeans did not feature in this argument. Indeed, Hanson’s key adviser and the author of much of her early material was a larger-than-life figure named John Pasquarelli — obviously not an Anglo-Celtic name, though Pasquarelli said he’d been “dewogged.”

I may have been inclined to accept that I, too, had been “dewogged” — but another experience intervened. With my Australian studies students in Brisbane, I was surveying the debates over “suburbia.” We looked at numerous critiques, as well as Hugh Stretton’s famous claim in Ideas for Australian Cities that Australians had adapted the suburb to their own needs, desires and imaginations. I began thinking about the northern Melbourne suburb in which I had grown up, Thornbury, and realised that my own experience of suburbia was different from that described in most social criticism.

I lived in a house with my mother, father and younger sister. To one side of our home lived my mother’s maternal uncle, with his wife. Next door to them lived their own son, with his wife. An opening allowed you to walk between the backyards of those two houses. On the other side of our own home lived my mother’s paternal uncle, with his wife. Behind them lived their daughter and son-in-law, with their young children. Again, a gateway led from the backyard of one home into the other. These arrangements allowed younger people to keep an eye on the ageing Italian-born generation while easily enlisting grandmothers and grandfathers as childminders.

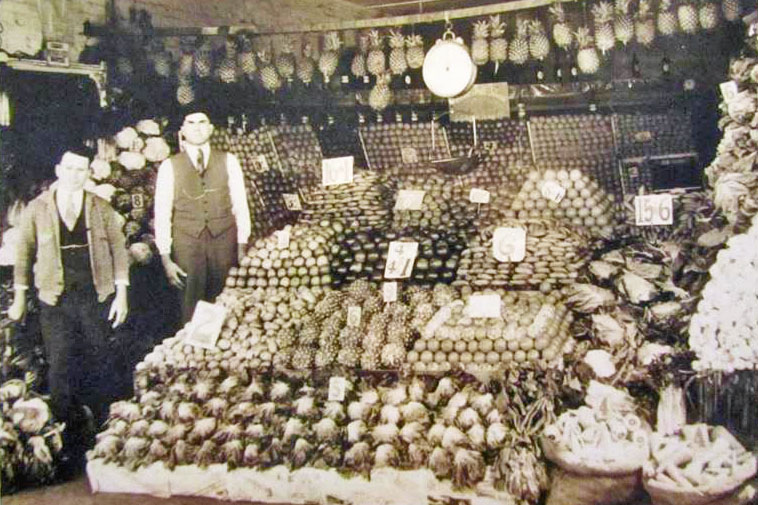

Frank Matisi (left) with an employee outside his shop in High Street, Croxton, c. 1929.

To Hanson, this might have seemed like a ghetto, but those living in it also participated in the wider community. My grandfather’s brother, one of our next-door neighbours, was elected to the Northcote City Council with Labor Party endorsement in 1962, served for more than twenty years and was mayor for three terms. He was active in CO.AS.IT., the Italian welfare organisation, and in Rotary. My mother’s cousin, two doors up from us, was a member of the Aeolian Club, but also active in the Lions Club, as were my parents. The relationship of these Italian Australians to one another and their community could not be captured in the easy clichés of right-wing politicians and conservative professors.

I never imagined that my mother’s family had been able to replicate in Melbourne the “Italy” they had left behind. Yet I also found it implausible that their ethnicity was irrelevant to the world they had made in the Melbourne suburbs, or that — like Nino Culotta and his son — they had slipped quietly into grey suburbia. There had to be an in-between place.

I visited Italy for the first time in 1997; I was in my late twenties. I saw this as a holiday, not a pilgrimage, but I did ensure that the Aeolian Islands were on my itinerary. The day before I left Lipari, I decided to try to find the house where my grandfather had lived. I knew it was in a village above the main port, and I hailed a cab.

At first the driver was incredulous that I wanted to go to this place on a Sunday morning. The village, at the top of a steep hill, seemed deserted, but we eventually spotted a man working in an orange grove. He hadn’t heard of my grandfather but suggested I ask someone over at the church, where mass was being held. I waited outside and when the service was over, the villagers started to emerge. I had little luck finding anyone who could speak English until one man pointed me towards a young woman about my age. “Do you speak English?” I asked. “Yes,” she replied. “I’m from Sydney.”

Once my mission was explained, and with the young woman acting as interpreter, the man to whom I had originally addressed my question quickly took me to the house in which my grandfather had grown up. I recognised it from photos. Very soon, the locals I encountered were able to connect me in their minds with those of my family they knew, either from the islands or in Australia. They knew my great-uncle because, in their eyes, he had become a big man, and because he and his wife had visited from time to time. They gave me coffee, fed me chocolates and presented me with homemade biscuits for the journey to Palermo. But they also insisted on taking me to visit my “family” on the islands.

The mental maps of many of these islanders included bits and pieces of an obscure country on the other side of the world, the Australian suburbs in which they had brothers and sisters, nephews and nieces, aunts and uncles and cousins. The great Australian historian of modern Italy, Richard Bosworth, has called this the “Empire of the Italies,” arguing that “for many Italians, the more obvious and decisive frontiers were not located in a printed atlas but wherever their minds or custom advised.”

Nino Culotta’s outsider status when he first arrives in Sydney is based on his inability to comprehend the Australian idiom. His epiphany — which occurs at the blokeyest occasion imaginable, a buck’s party — concerns his ability to think in Australian English. Nino is happy that his own son will be unable to speak Italian, and that he himself will forget how to speak it, and so have trouble conversing with his own parents back in Italy. He brands as “disgraceful” parents he sees in shops “talking to kids in their homeland language, and the kids translating into English.”

I was raised in an English-speaking home by parents who spoke Italian — including the Aeolian dialect — but only used it when dealing with Italians. Yet I do not speak Italian, and neither do the other Italian Australians of my generation in my extended family. This meant we only had outsider status in the Italo-Australian community, and I was always conscious of the cultural differences between myself and the “really” Italian kids (who usually had Italian-born parents) at school.

Other differences came down to whether one’s family was among the relatively small numbers of migrants who had entered Australia before the second world war, or from the mass emigration from the 1950s to the 1970s. Hairstyle, dress, taste in music, whether one liked soccer more than Australian Rules football, accent, whether one spoke Italian: these were all critical markers of identity.

The choices you made, or that your family had made on your behalf, determined the nature of the cultural capital you acquired. Could you plausibly claim the privileges of full membership of the still Anglo-Celtic-dominated community with the cultural power that entailed? Or did you belong to an accepted minority of the kind that had “enriched” Australian life through its spaghetti and soccer? Ghassan Hage has described this process well: it is all about who gets to control the terms on which national space is imagined, entered and experienced.

Assimilationism did influence the life choices of immigrants and their children. Ironically, it may have had a greater impact on the earlier generations than on those who entered under the postwar program and were officially subject to it. Many of the prewar arrivals, a small minority, had suffered persecution in Australia during the second world war, and had every reason to want to blend in after it. Some, including my Uncle Tony, who later became the mayor, were interned as enemy aliens. “Getting on” meant playing by the rules of British Australia. The Aeolian Club in Melbourne had enjoyed a membership of 200 before this war, but only forty-one renewed after it. The club became very dependent on the new postwar waves of immigrants.

The children of migrants had little incentive to ensure that their own children learnt Italian. It was more important to acquire skills that would help you to get on in life. Some likely believed that speaking too much Italian at home would harm their children’s English. My parents avoided giving their children Italian names. I was named after my maternal grandfather, Francesco, but became Francis. My parents would not have seen this as in any way anti-Italian or anti-Aeolian. It was simply about fitting in, adapting to the new.

Many of my own generation of Australian-born Aeolian Australians became quite detached from the cultures of their parents and grandparents, even as they also experienced fragments of these cultures in their daily lives — through food, snatches of the Aeolian dialect and barely articulated habits of mind. And there was the instinctive turn to extended family when you needed or wanted something, and the desire to touch government only with a very long pair of tongs.

Some, like me, entering their twenties, donned backpacks and used the financial rewards from professional jobs of which their grandparents would not have dared dream to visit their ancestral homelands. Now, as we get older, we travel there in more comfort. Relatives on my father’s side of the family assemble on Salina every few years for a family reunion.

Their Australian story has been the familiar one of migrant success, as celebrated in From Volcanoes We Sailed: Connecting Aeolian Generations, an exhibition at Melbourne’s Immigration Museum in 2016. Curated by my cousin, Cristina Neri, the exhibition shows how Aeolian-Australian experience was embodied in business and professional success, cultural continuity and a thriving family life. There was a great deal of nostalgia about food and families, and a sense that modernity and the passing of the migrant generation threaten both. When Russo wrote about the Melbourne Aeolian Club in 1986, she thought its future “precarious,” since the migrant generations were getting old, the community was well integrated and the young seemed little interested in maintaining these connections.

But the club — which sponsored the 2016 exhibition — now seems to be flourishing, and Aeolian identity is being reimagined by migrant descendants, who can happily pick and choose which bits and pieces of culture they embrace. We are free to ignore the patriarchy that consigned many women to inferior educational opportunity and to the home — that belongs to the past, as another country — while celebrating spicchitedda and other delicious treats of the kind made in the well-stocked kitchens ruled by those very same women.

The unrelenting gentrification of Melbourne’s inner suburbs has seen the demolition of the home in which I grew up, replaced in recent years by stylish townhouses. Years ago, newer immigrants — Greeks and Lebanese — moved into other homes on the block that had once been occupied by my family. Soon, most signs of the little world made by this group of Melbourne Aeolians in our street will be gone. But the traces of these islanders have not been so easily obliterated. In an era of globalised identities and easy mobilities, their descendants are reimagining their own “Empire of the Italies” as a reflection of their affluent, progressive and cosmopolitan selves. •

This essay appears in GriffithReview69: The European Exchange, edited by Ashley Hay and Natasha Cica, published in partnership with the Australian National University. Reference can be found there.