The Oxford English Dictionary defines satire as “the employment, in speaking or writing, of sarcasm, irony, ridicule, etc. in denouncing, exposing or deriding vice, folly, abuses, or evils of any kind.” That’s fine if a little flavourless, but then most dictionary definitions are. Most but not all. John Clarke, the New Zealand–born satirist who arrived in Australia in the 1970s and acquired a nasal local accent that he then deployed deadpan to devastating effect, once tried his hand at a definition of satire: “Noun: a reaction to the process whereby politicians and public figures hold the community up to ridicule and contempt.” This is much better, not least because the definition itself makes a satirical point.

It also offers a key to the power of Clarke’s satire: his brilliance in adapting forms, especially media forms, for satirical purposes. This can be seen in his remoulding of staple journalistic forms, ranging from standard news reports to sports commentary and the interview.

If all Clarke did, though, was parody journalistic forms, his work would not have risen above the level of a television sketch show. Instead, he inverted these journalistic forms to ask questions and critique those in positions of power and authority. According to conventional understandings of the news media’s fourth estate role, scrutinising power and authority is exactly what journalists do. Clarke was not a journalist; indeed, the failings of journalism were a common target of his satire. Yet his adapting of journalistic forms carried the bite both of satire and of revelation.

His work was genuinely subversive, though he was careful never to advertise it as such. It took the trained eye of Barry Humphries to point this out. In a foreword to a selection of Clarke’s work, the creator of Dame Edna Everage writes:

John Clarke sees the skeletons in our closets, and I am amazed he has not grown very rich on offshore hush money. In Australia the Powers that Be are very powerful indeed and are protected by draconian laws of libel that would make an Australian Private Eye unthinkable. The press bullies, hoods and monomaniacs who hold, or have recently held, high office demand critical immunity. Fortunately for John Clarke he can always be dismissed as a harmless wag, an amusing ratbag and an anodyne parodist. If he told us what he sees and what he knows about Australian society in any other way but his Jester’s guise he would, long ago, have met with a very nasty accident.

From gumbooted clodpoll to national treasure

Born in 1948, Clarke grew up in Palmerston North, a small town in country New Zealand for which he had fond memories but which, as he used to say, was “not exactly Vienna at the turn of the century.” At university he took to writing and performing in revues, where he slowly developed the character of Fred Dagg, originally a gumbooted, singlet-wearing clodpoll who spoke plain truths about those in power. He described the conservative NZ prime minister in the 1970s, Robert Muldoon, simply as a “well-known gross national product.”

Dagg became extraordinarily popular in New Zealand, but Clarke found the experience suffocating and migrated to Australia in 1977. Here, he spent time learning about the country before offering his work anywhere. “As a satirist I wanted to have a grip on things before I opened my mouth,” he said. When he did, Dagg had been transformed from a physical presence on television to a voice on radio. In the process, the contrast between the gumbooted yokel and the pithy truths he spoke became a contrast between a broad Australian-accented voice and a collection of truths expressed far from pithily. Instead, the language was by turns indirect, ornate, blunt and inventive, as this 1981 Fred Dagg commentary on home buying makes clear:

Like so many jobs in this wonderful society of ours, the basic function of the real estate agent is to increase the price of the article without actually producing anything, and as a result it has a lot to do with communication, terminology and calling a spade a delightfully bucolic colonial winner facing north and offering a unique opportunity to the handyman.

Operating out of the mythical Dagg Advisory Bureau, Clarke’s ninety-second monologues were soon syndicated across the ABC’s many local stations. They ranged from topical comments on, say, progress or lack thereof at the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, to dissections of particular industries, such as advertising (“We kicked off with a light lunch that lasted about five hours.”). At the height of its popularity, however, the segment was taken off air by ABC management for reasons that were not at all clear but clearly infuriated its creator.

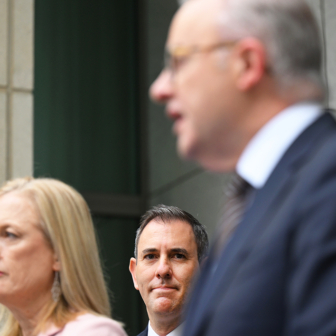

Clarke nevertheless became one of Australia’s most successful satirists, much loved by audiences and revered by peers. His work appeared in newspapers including the Age (his mock newspaper quizzes) and the National Times (in a column entitled “A Month of Sundays”), the Bulletin (early versions of his question-and-answer interviews) and Brian Toohey’s Eye, where he adopted Damon Runyon’s style and argot to portray politicians as gangsters. Much of his work has been reprinted in books and on his website. He was part of the pioneering satirical television series The Gillies Report, which broadcast in 1984 and 1985. In recent decades, he was most often identified with the mock question-and-answer interviews he produced with Bryan Dawe, which first appeared in print and on ABC radio in the late 1980s and were then aired on television, on Channel Nine’s A Current Affair between 1989 and 1996 and on ABC television, mostly on 7.30, since 2000.

Apart from writing and performing his own material, Clarke worked with many other artists: as an actor (with Sam Neill in Death in Brunswick in 1990), as a collaborator (with Paul Cox on the Australian Film Institute award-winning feature film Lonely Hearts, in 1981), as co-author (with Ross Stevenson of the stage production A Royal Commission into the Australian Economy, in 1991), as an adaptor (of Aristophanes’ The Frogs for Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney, in 1992), as dramaturg (for Casey Bennetto’s Keating: The Musical, in 2006) and as the creator of documentaries (such as Sporting Nation, in 2012). Sometimes, he worked on the writing, producing and performing of a program, as in the mockumentary The Games, which examined bureaucratic ineptitude and political chicanery during the two years of planning for the Sydney Olympics. He and Andrew Knight also co-wrote a satire, Blockbuster, about how films are funded in Australia; not altogether surprisingly, it found little favour with film-funding bodies and has never been made.

The Clarke technique

The breadth of Clarke’s career is clear; what is less evident from this brief summary is the nature of his humour and how it sits in the broader Australian tradition. Though he rarely discussed his ideas about satire, he did open up in Wanted for Questioning, a 1992 collection of interviews with thirty Australian comedians by Murray Bramwell and David Matthews, perhaps because the authors were academics and he judged the book would be read by few. In any case, what he said is worth quoting at length:

You could argue, as I have done, that Australians are very pungent, disrespectful of authority… and that they give the people in power a constant caning… But you could argue that the government in this country, by and large, is not that powerful and that there have been a series of recent prime ministers who have been failures and tragedies of almost Shakespearean dimensions. That the real power in Australia is held more obviously by a small group of billionaire bullies than is the case in Britain – and they are not the people that get the caning. So it could be said that satirists, about whom it is often said that they are such great snipers, are constantly shooting the messenger.

Clarke is referring partly to the entrepreneurs who made a killing after the Hawke Labor government deregulated the financial system in Australia in 1983, but primarily he is talking about the concentration of media ownership in Australia, which in many ways has become worse, not better, since that interview. What is also clear in the quotation is his high ambition for satire. In a review of The Oxford Book of Humorous Prose, Clarke criticised the editor, Frank Muir, for describing Jonathan Swift as a bitter character who “could hardly be called a humorous writer.” For Clarke, Swift was among the greatest satirists because “he attacked greed and corruption wherever he saw them and he smote the authorities hip and thigh” while Muir “does everything he can to defuse any effect humour might have other than to amuse the clergy.”

In Clarke’s view, satire needed to have a social purpose. It should go beyond a prime minister slipping on a banana skin, and shouldn’t simply blow raspberries at those in power. “I think satire is helpless if it doesn’t have a positive aspect,” he told Bramwell and Matthews. The book’s title was Clarke’s but readers didn’t know that, which illustrates not only his subversive wit but his generosity and tendency to small-note himself. (That’s a grateful homage to Mr Clarke, by the way, who taught me the bite of inverting a common phrase.)

Clarke thought that a satirist should think about solutions as well as problems. He never kicked somebody because they were down, but he also thought there was little point kicking somebody simply because they were up. “I do think there are issues and paradoxes and I think it is hard to express an idea without conceiving its opposite.”

One-time collaborator and long-time Clarke friend Andrew Knight once told me, “I think the yardstick of any satirist is how much they are disliked [by their targets] but he is the most generous and encouraging person in an industry that is cancer-ridden with people who want to jump on you.” The wonderful humanity attested to by Knight and many others this week does not mean Clarke viewed the world’s woes with bland equanimity. Andrew Denton, himself a well-known satirist, has said, “At the heart of all great Australian comedy is a red hot kernel of anger.” He could have been speaking about Clarke who, to meet – and I met him and wrote about his work on several occasions – could seem like a roiling well of outrage.

Clarke shied away from direct confrontation, however, which to him “is very often an affair where people repeat their positons and become polarised, which makes it difficult for either party to back down.” Instead, he expressed his “red hot kernel of anger” about the world indirectly through satire and, within that, indirectly through elaborate metaphors. Unlike, say, John Oliver or The Chaser team, who attack their subjects front-on and at full throttle, Clarke compressed and recalibrated the intense emotions he felt into satirical conceits that appeared to have no animus, as Barry Humphries has written, but still knocked the target akimbo.

Paradoxically, despite the range of roles Clarke played and projects he participated in, he almost always presented a version of himself. He was not a character actor. Whether he was playing Alan, a stage hand for a decidedly amateur theatre company in Lonely Hearts, or Dave, Sam Neill’s offsider in Death in Brunswick, he was pretty much the same: deadpan of face, laconic of voice, alternately world-weary and stroppy (Alan) or world-weary and stoically wry (Dave). For The Games, he dispensed with all pretence. His character, head of the Logistics and Liaison team, is called John Clarke and was, by turns, world-weary, stroppy, stoically wry and knowing. The other characters in The Games retained their own names, too, which added to the frisson of national anxiety that Australians felt about staging a global event such as an Olympic Games.

But while for The Games’s Gina Riley playing a version of herself was an exception – she is best known for playing Kim in the satirical comedy Kath & Kim – for Clarke playing himself was part of a continuation. You might deduce from this that Clarke was not a good actor, but he has said that in his childhood, when his mother used to take him along to an amateur theatre company she belonged to, he developed a suspicion of actors being actorly; he much preferred his mother when she was being herself. He was actually a very good performer but he insisted, consciously or otherwise, on doing it on his own terms.

Upending the question-and-answer interview

Just what were Clarke’s own terms? Well, you can see them most clearly in the mock interviews he did with Bryan Dawe. The Q&A interview is a journalistic staple in which politicians, celebrities and sportspeople have been trained – usually by former journalists – to avoid journalists’ questions or to verbalise at length. It has been pretty much spun dry. Where Clarke’s former colleague Max Gillies made his reputation for the uncanny precision of his impersonation of former Australian prime minister Bob Hawke and other politicians, Clarke never made any effort to impersonate the politicians and celebrities he satirised. Instead, he fielded questions from Dawe, as himself, while maintaining he was someone else. In the 1980s, the initial surprise at seeing a middle-aged, balding man wearing no make-up or wig speaking as if he is British prime minister Margaret Thatcher or actor Meryl Streep was funny enough in itself, especially when the latter engaged the interviewer in chit-chat about the “natural” colour of her/his hair and whether “Meryl” would wear a wig for her role as Lindy Chamberlain in the upcoming film Evil Angels.

More importantly, though, the decision not to impersonate the subjects allows us to focus on what they are actually saying. For example, in an interview in 1990, Clarke, as Bob Hawke, is asked about the science and technology minister, Barry Jones, who had just lost his place in the ministry because he did not have the backing of Labor Party’s factions.

Dawe: The Hobart conference seems to have gone very well.

Hawke: Fabulous success, standing ovation I got; they all got on their feet and ovated, right at me…

Dawe: How did the Barry Jones decision this week help with that healing process?

Hawke: I’d like to say something about Barry Jones if I may. He’s a very remarkable fellow. He it was who warned ten years ago that we had no manufacturing basis in this country and that the sunrise new technology industries gave us an excellent opportunity to get one. He it was who also warned of the greenhouse effect.

Dawe: Did we get any of those new technology industries?

Hawke: No, but the countries who listened to Barry Jones did…

Dawe: So how did Mr Jones help with this healing of the wounds within the party?

Hawke: By standing aside for a dumber man.

The first thing to notice is Clarke’s attack on Hawke’s vanity, underlined in the use of the arcane word “ovated.” The second is that good policy is no match for factional alignment (crystallised in the acid line: “By standing aside for a dumber man”) and the third, at the distance of twenty-five years now, is just how prescient Jones – and Clarke – were in identifying the importance of new technologies and the need for Australia to take action on climate change. Nor is this prescience an isolated event. Clarke’s commitment to examining issues in detail before satirising them means he consistently shot up warning flares.

Running to about two-and-a-half minutes each, the mock interviews usually contained one main satirical point that is prosecuted throughout. There is no space for digressions and no interest in providing a rounded or balanced view of the subject or issue.

Some of the most successful mock interviews turned on a comic conceit, such as one with Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, a National Party figure who owed his longevity as premier of Queensland to an electoral gerrymander and a garrulously folksy manner that cloaked a ruthless political warrior who had courted property developers and sent police on to the streets to crush any political dissent. In 1987 Sir Joh finally and fatally overreached, launching an ill-conceived tilt at transferring to federal politics that succeeded only in derailing the election campaign of his federal National colleagues and their coalition partners, the Liberal Party, as they sought to win office. Bjelke-Petersen had long been regarded (and underestimated) as something of a buffoon but, instead of making that obvious joke, Clarke’s satirical conceit was to write a script for “Sir Joh” as if he had always aspired to a career in the front rank of comedy.

Dawe: Are you the sad clown? The commedia dell’arte clown?’

Sir Joh: Well, I think I’m a very Australian clown. I think I’m a very Australian clown. I’m not immune to life’s bleaker side, obviously, but I don’t think I’m consumed by it either. I frequently find, for instance, the things which worry people a lot… I find very funny. personally, I find them very, very funny, and I wouldn’t want that to sound as if I don’t care.

The interviewer then presses “Sir Joh” to nominate a favourite joke he has played on the Australian public. For sheer laughter and audience response, “Sir Joh” can’t go past his “Joh for PM” campaign.

Dawe: Why do you think it actually worked as well as it did?

Sir Joh: Various factors. First of all, let me say that it had been done before. It wasn’t an original idea, people had been…

Dawe: But you brought something to it didn’t you?

Sir Joh: Well I like to think so. I had a lot of luck with the timing. For instance, for a start I announced I was running for prime minister when there wasn’t an election on.

Dawe: Yes.

Sir Joh: Pretty funny. Pretty funny.

Dawe: Yes it was.

Sir Joh: Right from the kick-off, I mean that is pretty funny. Then, an election was called, and where was I?

Dawe: Disneyland.

Sir Joh: Pretty funny. Pretty funny. Pretty funny. You’ve got to say that’s pretty funny. I had a lot of luck with the timing. It couldn’t have been better for me. There I am running for prime minister when there’s no election and then there is an election and I’m at Disneyland, being photographed with big-nosed people in the background and speaking of my personal… I mean it was pretty funny.

Dawe: Couldn’t believe your luck.

Sir Joh: Couldn’t believe my luck. On a plate. Literally on a plate.

Dawe: Sir Joh, thank you very much for your time.

Sir Joh: Thank you, you’ve been a wonderful audience.

Pretty funny indeed. You notice how Clarke mimics a conventional chat-show style so that the interview gradually becomes a conversation which leads us to notice the contrast between the smoothness of the chat and the stumbling circumlocutions we were used to with Sir Joh. And, finally, we see that the mock interview does not aim to capture Sir Joh’s character but draws our attention to the impact of his behaviour on ordinary citizens.

Just as it is commonly said that newspaper cartoonists can achieve with a few brush strokes what it takes journalists hundreds of words to say, so the same has been said of the mock interviews. For the everyday person who alternates between feeling powerless to influence governments and anger at being told lies about what they have done, there is something particularly satisfying in satire such as Clarke’s. Either the politicians’ dissembling is pierced by his laser-like scrutiny or they become puppets controlled by the satirist and made to reveal their behaviour.

So, when Australia’s federal treasurer in the 1980s, Paul Keating, a man who had long been on very good terms with himself, led Australia into what he described as “the recession we had to have,” he was made to say in a mock interview the very words he would never have uttered: that the state of the economy was his fault and “Tell the people I’m sorry.” This is a distinct advantage satirists enjoy over journalists. As Peter Meakin, former head of news and current affairs at Channel Nine, once commented, “When Ray Martin [then the host of A Current Affair] is interviewing Paul Keating, he is dependent on what Keating says.”

The unionisation of childhood or the childishness of unions

If Clarke’s inversion of the question-and-answer interview is his best-known satire, and his invention of the mythical sport of “farnarkeling” one of his most loved creations, I’d like to finish by reminding readers of his reworking of the standard news report to portray the particular pleasures and perils of raising children. The impersonal style and formal tone of the news report have long been the subject of parody and satire; Clarke’s contribution was to use it to report the activities of the Federated Under Tens and the Massed Five Year Olds. Writer Shane Maloney has said these pieces of Clarke’s are a commentary on the childish behaviour of many trade unions, which is certainly plausible, but for me the tone is of an exasperated but loving parent rather than an aggrieved citizen. As you will see, I trust.

Australia ground to a virtual halt on Tuesday when the Federated Under Tens’ Association withdrew services, stating that in their view it was an unreasonable demand that they wear a sun hat in the sun. They further suggested that the placement of sunscreen lotion on or about their persons was an infringement of basic human rights and was “simply not on.” Wednesday saw the dispute widen when an affiliated body, the Massed Five Year Olds, showed their hand by waiting until management had about a hundredweight of essential foodstuffs in transit from supermarket to transport and then sitting down on the footpath over a log of claims relating to ice cream. The Federated Under Tens, sensing blood in the water, immediately lodged a similar demand and supported the Massed Five Year Olds by pretending to have a breakdown as a result of cruelty and appalling conditions.

The problem had been further exacerbated by a breakage to one of the food-carrying receptacles and some consequent structural damage to several glass bottles and a quantity of eggs, the contents of which were beginning to impinge on the wellbeing of the public thoroughfare.

As far as I know, only three of these short monologues have been reprinted in Clarke’s anthologies, but what is striking about them is the precise use of jargon (industrial in this case), the satirical conceit (of parenting as a never-ending negotiation) and the deliciously chosen words (“beginning to impinge on the well-being of the public thoroughfare”). With a topic like parenthood, which taps many people’s deepest feelings of love as well as frustration, Clarke doesn’t express his feelings directly but deflects and reshapes them into monologues that convey, albeit indirectly, something essential and well-nigh universal about how it feels to raise children.

This appraisal has covered only a portion of Clarke’s work and does little more than begin mapping his satirical brilliance and influence. If it is undeniably tragic that he died at such a relatively young age, it is equally true that his forensic intelligence is needed now more than ever. The bullshit-detection business has lost one of its finest exponents. •