A few years ago I travelled to Woodford, on the outer edge of northeast London, for an event to commemorate the life and work, and in particular the local connections, of Sylvia Pankhurst, the campaigner for the rights of women and many other good causes. Sylvia had come to Woodford in 1924 after her strenuous efforts to win votes for women, agitate for poor women in London’s East End (“that great abyss of poverty”), oppose the war, and inspire an international workers’ revolution. (The latter passion brought her into conflict with Lenin as she took her stand with the ultra-left of the communist movement.)

Woodford was a prosperous, conservative parish on the edge of the ancient Epping Forest. The arrival of the railways, and more recently the underground, had unified London and, here as elsewhere, made possible the new kind of development the conservationist and poet John Betjeman would call “metroland.” Woodford’s air suited the higher class of civil servant, City gentleman and politician. Clement Attlee, another patrician radical who had done a stint in the East End, lived here; Winston Churchill was elected local MP months after Sylvia moved in, and would remain so for twenty years.

Both men were to attain the summit of power in the 1940s. In the span of Sylvia’s own extraordinary life, her years in Woodford might appear a retreat from activism rather than a springboard. But after two epic decades, her energies were refocusing rather than drawing in. While living there she wrote huge books, corresponded and campaigned indefatigably, and scandalised neighbours by cohabiting with her second great love (after the founder of the Labour Party, Keir Hardie), the Italian revolutionary Silvio Corso. The couple lived in a house they renamed Red Cottage, and opened a teashop catering to day-trippers on their way to the forest.

Ethiopia’s invasion by fascist Italy in 1935 gave Silvia a new cause. Indeed, she was “one of Churchill’s most vociferous constituents” on this and other subjects, taking him to task for his complaisant stance towards Mussolini. On the invitation of the emperor, Haile Selassie, she left Woodford in 1956 to make her home in Addis Ababa with her son Richard, who was already becoming (as he remains, in his late eighties) a respected scholar of the country.

She had also taken a close interest in her London environs. Indeed, among the speakers that day in Woodford – who also included Germaine Greer and the cultural historian Patrick Wright – was a local historian who described the relationship between conservative Woodford and the radical Sylvia in terms of wariness gradually leavened by amusement. One of his recollections was particularly memorable. Sylvia’s range of acquaintances included local farmers, several of whom had lived all their lives around Woodford and yet had never been to the city, whose skyline, nine miles away, was visible from the fields they were working.

This detail raised an echo of Melanie McGrath’s family memoir Silvertown, published in 2002. Its tale is rooted in that neck of east London’s docklands whose menfolk once unloaded sugar and other booty of empire from huge wharves while women in nearby factories processed it into gooey sweets. The book’s valuable social history is concentrated in the figure of Melanie’s grandmother, Jenny Fulcher, who was born in 1903 (the year the twenty-one-year-old Sylvia helped her then more prominent mother Emmeline and sister Christabel to found the Women’s Social and Political Union). Jenny worked in a clothing factory, where her hands were scarred by the crude tools, survived poverty and pulverising wartime air raids, opened a cafe, endured an unhappy marriage, and found endless comfort in Silvertown’s confectionery range.

Her granddaughter honours Jenny at the end of her life:

So there she was, at ninety-one, a tiny woman with no teeth who had borne two children but had never seen a naked man; a woman who had been born in London but had never visited the Tower or St Paul’s; a woman who would not talk to her local shopkeeper in case she had to pronounce her name. But a woman whose strong sense of place it is hard for me to imagine. Jenny Fulcher was someone who belonged.

In turn, the mental relocation from Woodford to Silvertown reminded me of a vignette in Roger Mills’s book Everything Happens in Cable Street, published in 2011. This is a lovingly researched collection of memories of that ribbon-like thoroughfare just north of the docklands, most famous for the “battle” of October 1936 in which Oswald Mosley’s fascists were prevented from marching through a substantially Jewish area. (In a familiar pattern, scholars struggle in vain to demythologise that incident.) Like McGrath’s, and all good “local” books, this one conveys the sense that the neighbourhood it documents was the centre of the world for its inhabitants.

Alongside the tale of the Japanese merchant sailor who lodged near Cable Street in the early 1900s, left a parrot in lieu of rent and then failed to return – thus “The parrot that spoke only Japanese” – is one of a girl about to start work in the 1920s in a job that involved travelling the short distance west to Aldgate, the busy junction where the East End ends (or, from the west, begins). Her mother was alarmed. Aldgate! What might happen to you there?

The area of Bethnal Green, a few streets north of Cable Street, was the site of a three-year research project by Michael Young and Peter Willmott, in the 1950s, seeking to understand “the effect of one of the newest upon one of the oldest of our social institutions” – respectively, the housing estate and the family. The co-authors’ household survey and interviews, filtered with calm confidence and lucidity, made the resulting book – Family and Kinship in East London, published in 1957 – a landmark of social history as well as of modern sociology.

The controversy over the work that began with its publication (was it overly sentimental, selective, middle-class in its lens?) continued for decades. Yet the inestimable value of the book was widely acknowledged: its recording of a way of life at a moment when forces that would spell its end are gathering pace. In the next decades, many of the “old” East Enders would continue to be rehoused in high-rise flats and relocated to new towns such as Dagenham, then just beyond London’s eastern boundary, as a fresh immigrant cohort – mainly Bangladeshis – began to arrive.

Michael Young’s parents were Australian and Irish, and his first eight years were spent in Melbourne. His energies moved between politics (he drafted the Labour Party manifesto in 1945), research, writing and social innovation (the Consumers’ Association, the Open University and the Institute of Community Studies, or ICS, are three of many organisations he founded or conceived). Along with his substantial achievements, this transgressiveness makes him seem the kind of figure all too rare in Britain: perennially modern and democratising.

In 2000, I had the good fortune to meet him in his ICS eyrie on Bethnal Green’s idyllic Victoria Park Square. (With a spark of genius, the institute was renamed the Young Foundation after his death in 2002 at the age of eighty-six.) As he scooped his regulation lunch, a tin of Heinz tomato soup, we talked about a successful recent project he had initiated, a phone-based translation service allowing Bangladeshi women (for example) to obtain health advice.

He spoke of the intense localism of the old East End. People didn’t just belong to “Bethnal Green” but to particular streets within it. Some could recall the sole occasion on which they had left the borough, usually on a day-trip to Southend on the Essex coast. (At this point I mumbled a Scottish comparison. He paused, gleamed, said “You’re Scottish – I thought you were German!” and then, offering his hand across the table, “Friends again!”) One man referred to the old people’s home where his elderly mother lived as “over the water,” meaning the south bank of the Thames, a mile or two distant. It sounded like another world, “as far as the moon.”

These are snapshots of a vanished past. But they have echoes in the modern city, even if these tend to be muffled by demographic transitions, shiny surfaces and aural kaleidoscopes. The entire lives of many in London – including in today’s Bethnal Green – continue to be circumscribed by a few streets, the area beyond unknown or alien. “London is whatever can be reached in a one-hour walk,” wrote the lodestar of now ultra-cool psychogeography, Iain Sinclair.

A Somali friend who runs a small technology shop recently told me he had left his north London niche twice in the last two years, both times to visit relatives near Mogadishu. Many studies of kids in trouble, such as Harriet Sergeant’s fine account of how she got to know a south London teenage gang, Among the Hoods, note how confined is their world. True, more education, money and freedom mean greater mobility, imaginative as well as physical, including the route to work; but even higher up the scale, Londoners’ ability to bind themselves to a small area of the huge city and make it theirs, to choose local attachment and feel its tug, is striking.

By some mix of necessity and choice, almost every old Londoner is born, and every new one becomes, a localist (if also a “cosmopolitan localist,” in Luis Moreno’s useful term). London’s outward-facing reputation is as a “world city,” shaped over centuries by forces – power, trade, empire, migration, globalisation – that have absorbed people, offered them opportunity, impinged hard upon them, and obliged them to cope. But from the inside London is very much a “local city” too, a reality underpinned by its social geography and governance (Lewis Mumford described London as a “federation of historic communities”).The infinite is ever balanced by a pull towards the intimate. It’s part of London’s accidental genius that these elements have continued to interweave, each containing and entering the other. A mix of global, historical, civic and organic elements gives London what is most enduring and familiar in its character.

This is symbolised above all in the transport network, especially as conveyed in two masterpieces of modern design where the individual can visualise both the city entire and her or his own place within it: the classic underground, or “tube,” map designed in 1931 by Harry Beck, and the London A-Z, the indexed street map created by Phyllis Pearsall in 1936. A line and route on the map signifies that place. Around it is a further constellation – a borough, a neighbourhood, a street, a cluster of shops, a familiar building or landmark, a corner, all the way to Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own.” Along the route, something changes. It may not go as deep as Jenny Fulcher’s, or demand so much or last as long. But that something is also how, if you weren’t born one, you become a Londoner.

London’s very mix, its all-human-life-is-here aspect, makes it a place where anything said about it can be qualified by the opposite. It’s crowded, yes, but retreats are everywhere. It’s a concrete wilderness with a green oasis across the road. The fetish of height that grips its skyline is undercut by the longing for a human scale. It’s cold and friendly, abrupt and gentle, frenetic and calm, dirty and fresh, monochrome and colourful – all in the space of an hour.

That variability extends to the intense arguments now under way about London’s economic and social direction, and about the city’s impact on the rest of the United Kingdom. Is London, which produces around a fifth both of national GDP and of its tax revenues, a success story that benefits Britain, or a fantasy island that strangles it? Celebrants and doomsayers find evidence to make diametrically opposing cases with equal certitude.

The former point to the way that since the financial hammering of 2008–09, London has been in the vanguard of Britain’s economic recovery (which in turn compares well with the flatlining eurozone). London’s lead over other regions on most major indices – output growth, employment, investment, start-ups, incomes, tax revenues – owes much to structural factors that give the city its exceptional resilience. These include size, strategic location (in relation to both Europe and global time zones), institutional stability, diversity and concentration of skills. The city has expanded to 8.5 million people – as many as in Scotland and Wales combined – with 37 per cent of them born outside the United Kingdom. London’s undiminished ability to absorb immigrants, most of whom are young, tens of thousands arriving after Poland and the other east-central European states joined the European Union in 2004, is testimony to its ingrained optimism.

London has other prime assets. It is a global financial centre, transport hub, seat of government, tourist destination, site of unmatched networks of expertise, and home to leading businesses, universities, media and cultural institutions. The very synergy of all these factors adds further rocket-fuel. Success feeds on itself (and indeed, the buzzing culinary culture should be added to the list). Other British cities are doing well in the rebranding business, often with culture in the vanguard – Newcastle, Dundee, Hull, Bristol – but it is no criticism of them to say that London’s range and cachet give it permanent premier-league status.

In response to these “boosters,” the “begrudgers” offer a much less flattering vista of modern London (the coupling is Roy Foster’s, in Luck and the Irish, his forensic analysis of Ireland’s three decades from 1970). London may be galloping, but towards increasing inequality and inequity, underpinned by an economic model tilted towards plutocrats (often of dubious vintage) and the very highly paid, and away from almost everyone else: hard-pressed workers (often part-time and low-wage), young people, recent immigrants, and those dependent on fixed incomes and welfare.

London, in this view, is characterised by “growing inequality and drift towards being a tax haven for the world’s super-rich” (Danny Dorling, professor of geography at Oxford University, writing in the New Statesman), or is perhaps a “wonderful city whose grip on national life is now endangering the country’s survival” (the Financial Times’s Matthew Engel). These trends, facilitated by the Conservative-led government’s indulgence of the already privileged, undermine national cohesion and social fairness. Britain is in effect being run for the benefit of a rich minority in London; the city’s dividends, including lavish infrastructural spending, make it a “giant suction machine draining the life out of the rest of the country” (Vince Cable, the avuncular Liberal Democrat business secretary in the increasingly pantomime-horse coalition government).

There is a lot more in either vein, both jubilant and gloomy. But there is also a view, common across a wide spectrum, that London needs rebalancing, both internally and in relation to the country beyond. Among the live issues is London’s governance, in particular how the model introduced by Tony Blair’s government after 1997 – an elected mayor and assembly with responsibility for city-wide services, including transport, and some planning functions – could be extended. As the next elections in 2016 approach, with the jockeying to be Boris Johnson’s successor especially keen on the Labour side, a prominent theme will be redrawing London’s powers so that they better serve the great majority of Londoners.

The argument that London needs greater self-government has been sharpened by the Scottish referendum process, and the substantial levers over taxation that Scotland will soon secure (if the recommendations of the all-party Smith Commission are legislated). In the argument over the United Kingdom’s future, London felt constrained in promoting its own interest as long as Scotland’s breakaway seemed possible. Now, though, it has no reason to hold back.

Why, ask columnists in the Evening Standard – the city’s free, and very successful, daily paper – should London not have the same autonomy, and ability to shape its economic future, as Scotland? The reform of stamp duty on house purchases by the Conservative chancellor, George Osborne – announced on 3 December in his “autumn statement” on Britain’s finances – will have a disproportionate effect in London, with its concentrations of wealthy property. Surely, then, Londoners should benefit from the proceeds? This is just one policy area that accentuates the belief – unlikely though it can seem to those raised on a diet of hegemonic London – that the argument for greater democratic accountability can also be applied to the metropolis. Tony Travers of the LSE, foremost specialist in London’s governance, has spoken of the rise of a “near London nationality,” accentuated by perceived tax unfairness.

True, London’s interest within the ever-evolving British constitutional settlement has to be measured against the claims of other regions, including the north of England, where the proposed Scottish package is also concentrating minds. (Edinburgh’s control of aviation fuel tax, for example, will give it a competitive advantage over airports across the border.) The government-backed City Growth Commission has led the case for an integrated approach to planning, transport and investment that would link Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield and other cities, thus creating a so-called “northern powerhouse.” A consensus on the political and constitutional aspects of this regional project, or even on its boundaries, has, however, yet to be reached.

In this respect London, like Scotland, has the advantage of an existing institutional architecture and a coherent sense of self-identity. Several think tanks and their specialist units have been or are weighing the reform possibilities. The London Finance Commission’s report of May 2013 – set up by the mayor, with Tony Travers as chair – pressed for the city to control its business rates and property taxes, noting that 74 per cent of London’s funding comes in the form of a grant from central government, three times that of Berlin and nine times of Tokyo.

The Centre for London’s manifesto for the city, written by Ben Rogers and published in October, echoes this view. “London’s star shines almost too brightly,” it says. “Its very success is putting huge pressure on housing, infrastructure and living standards – at a time when public money is in short supply.” It recommends that London should have more powers over the taxes generated there, and over regulations and social services (such as planning and welfare), as well as make its governance more accountable and improve links with – even expand into – its hinterland.

All this emphasises the fact that the “London” of boroughs, voters, workers and neighbourhoods, and the “London” that symbolises the site of the United Kingdom’s central – and still over-centralised – government, are not the same. (There is also a third dimension: the City of London, both medieval city-state with its own mayor, corporation, land, privileges and residents, and host to the financial district which helps sustain Britain’s global niche.) Outside the capital, the first London tends to disappear under the other two; but it exists, and most of its inhabitants can’t afford the luxury of being either boosters or begrudgers. This London is busy refitting itself for the trade-offs that may usher in a more federal and democratic – though also messy and uneven – United Kingdom.

When people in Britain see London as exceptional, it is above all housing that they have in mind. Since the 1980s, the city has concentrated and amplified the dominant trends of Britain’s housing economy: a turn towards home ownership (accelerated by the transfer of many council houses to the private sector), successive price bubbles, ultra-sensitivity to interest rates in the context of enormous mortgage debt, a tightening rental market, and a deficiency of supply as population has risen and house-building has not kept pace with demand. Through all this, house prices acquired the status of a national obsession, though always questionable as a measure of real wealth.

In recent years, London’s housing market has become even more a world of its own. Prices have soared far beyond the capacity of people on modest salaries. The average price in central London has grown by 44 per cent since 2009, and is now around £500,000, more than double the national figure. The number of affordable properties is way short of demand, while rents have also increased exponentially. Those in search of a place to live, without the security of an existing family home – 180,000 households are on waiting lists across the city – are squeezed every way they turn. Moreover, the purchase of properties by wealthy buyers (including from Russia and east Asia, often for investment as much as residence purposes) further skews the market and accentuates the vast and growing disparity between the high-end incomer and the would-be mortgagee and renter.

Wealth and poverty, extremes of comfort and hardship, have always coexisted here; today, the more precipitous divides (over income and life-chances as well as housing) are putting modern Londoners’ social compact, and the city’s competitiveness, under particular strain. The frenzy of overheating is captured in the Guardian’s “Let’s move to…” weekend profile, aimed at a young, urban demographic. The 21 November feature on Poplar in east London, which Cable Street runs through, has an exhortatory headline (“Be quick, the gentrifiers are coming”) but Tom Dyckhoff can’t even fill the “bargain of the week” slot. He concludes sadly: “When even Poplar is out of your league, you know something’s wrong.”

Indeed, people in their twenties and thirties struggling to get onto (or climb) the elongated “property ladder” are hardest hit. The rate of those moving out of London to provincial cities is increasing markedly, according to a new report by the Office for National Statistics. Everywhere, the less secure are finding innovative ways to share, lodge, cram, house-sit, squat or – no longer the last resort – go back to mum. The vagaries of “regeneration” can also oblige even settled residents with growing families to look elsewhere. Tim Sowula, a former colleague, writes in the Kentish Towner of his regret at having to leave his home area for distant Leytonstone:

The sad thing about moving out of Kentish Town isn’t necessarily leaving the area, but the sense that it may be impossible to live there again… Of all places, has it joined the ranks of London’s privileged communities? And has that gate quietly shut to most over the last decade?…

My personal situation is typical in that it raises a question of what will Kentish Town be like in the future if, for the first time, the traditional pool of people who could previously settle and have families – small business owners, creatives, public sector workers and middle-class professionals – can no longer afford the type of property that would allow them to do that…

A sad paradox of Kentish Town – and many other once earthy London neighbourhoods – now gracing homes and property pages is that getting “on the map” of cool areas means sliding off the map of where most folk can actually live. NW5 used to be a refuge for foreign people; now it’s becoming a refuge for foreign money.

The last point is well taken; over two centuries, a swathe of political exiles (Karl Marx included, as well as Joe Slovo and Ruth First of the African National Congress) found a haven in the ribbon of London stretching up through Camden and Kentish Town to Hampstead. Some of the artistic émigrés of 1950s–60s Australia also made a berth in “not yet trendy Kentish Town,” which along with Camden was then part of “the working-class and increasingly alternative inner north,” says Stephen Alomes in When London Calls: The Expatriation of Australian Creative Artists to Britain.

For Tim, whose article provoked a lively debate, there are consolations. Leytonstone is “still less than a half hour from the Heath (via the handy Gospel Oak line) with a vibe that reminds me of Camden in the eighties.” Thanks to that transport system, wherever you are, the whole city is always, well, your Oyster.

On a policy level, there are some positive signs: local councils such as Newham in east London, site of the Olympic Games in 2012, are working hard in tough conditions to provide affordable homes; architects have designed imaginative low-cost and self-build schemes; and pressure to develop derelict sites and make some of London’s many discarded buildings habitable is increasing. But where housing above all is concerned, a big yet targeted effort – and there is no shortage of proposals – is urgently needed. Something in London has to give.

The critics of London from inside tend to be frustrated patriots, writing in the spirit of George Orwell: London is a family with the wrong members in control. The real begrudgers are outside. Here is the deepest gulf between London and the rest: a psychological one, and as important as any material. The commuters who flock in each day from its wide orbit share the city’s rewards and stresses, but distance from the metropolis seems increasingly to lend disenchantment. The capital has often been seen (from Scotland, England’s regions, or Wales) as remote, privileged and unfeeling. In the context of people’s often straitened circumstances since the financial crash, of well-founded perceptions that government policy disproportionately favours London, and of gathering national or regional sentiments, this image too has gorged on itself.

The Londonphobic dish has been garnished with additional flavours – most with a long pedigree, but capable of taking new forms. They include a nativist and anti-immigrant sprinkling (often more coded than explicit), loathing of the financial sector and its scandals (which, justified in itself, can carry a whiff of moral superiorism towards the city as a whole), and all-purpose anathema of “Westminster” and its politicians (conveniently interchangeable with “London,” and vice-versa, depending on the target of the moment).

The London government’s control of spending and strategic planning entrenches regional dependency and encourages suspicion rather than collegiality – a tendency reinforced by Britain’s political map, with its inert blobs of Tory blue and Labour red (though other colours are leaking in from the margins). Even projects designed to connect England’s north and south – such as the high-speed rail link, or HS2, between Leeds and London, to be completed by the early 2030s – are viewed by many in the north as extensions of Vince Cable’s “giant suction machine.” (Vince himself, who represents Twickenham in southwest London, has come round to supporting HS2.)

Scotland’s referendum confirmed how attenuated the bonds have become between the various parts of the United Kingdom, how strong aspirations to quasi-independence from London now are, how vital are spending and fiscal powers in making those aspirations real, and how a slow dynamic of mutual disengagement, once released, is very hard to reverse. The intense and absorbing debate about whether and to what extent London benefits or damages the rest of the United Kingdom in terms of traditional measures of inward investment, taxation, and transferred revenue is unresolved. But its very terms suggest that London, at least in economic terms, might no longer “need” non-London. In its present form, London’s success is helping to disintegrate the United Kingdom.

The responsibility for the fate of the kingdom, however, is not London’s alone. The resentment towards the city has long taken on a life of its own, detached from its main source in the central government’s control of most financial levers and thus the ability to shape public policy. Much of the antagonism towards London has become misdirected, indiscriminate and self-flattering (reliant, for example, on near exhausted tropes of rootedness and authenticity). At the same time, it has its own “existential” logic. A place so big, rich and powerful tends to skew outsiders’ perceptions (vide the United States). In a sense, the extremes of affection and hostility London attracts derive from the same source: that the city is beyond compare.

London also has no domestic rivals, which enables it to capture cosmopolitanism and, without having to try, render everywhere else provincial (contrast Barcelona, Milan, Istanbul, Mumbai, Osaka, São Paulo, or Shanghai). In non-London, the city exerts the irritating trick of being unmatchable yet unignorable; like the fabled upas tree, nothing can grow in its shade. It’s all too tempting, then, to define yourself against it, using whatever is at hand to further your cause.

Anti-Londonism, admittedly, takes many forms. Scotland’s blend during the independence debate merits a study of its own. But it is striking how the once varied repertoire of attitudes to the capital has withered to a monotonously negative register.

The theme of an overbearing metropolis whose influence – carried ever further afield by its cash-rich settlers and their asphyxiating tastes – corrodes what it touches and reduces what it neglects, is drawn by the perceptive Matthew Engel in his new book, Engel’s England: Thirty-nine Counties, One Capital, and One Man. The book is an affectionate search for the surviving quirks of England’s historic counties, shadowed as ever in this genre by a lament for a land of lost integrity. (The many earlier excursions down the rolling English road include William Cobbett’s Rural Rides and J.B. Priestley’s English Journey, published respectively in 1830 and 1934. “The Thing,” Cobbett’s inspired term for the hated establishment, is a precursor to today’s “Westminster elite.”)

In an accompanying article on 21 November, Engel is scathing about London. The city’s “remorseless expansion, dominance and control,” he writes, means that today, “every part of the body has become defined by its relationship with this heart.” Across England he observes ubiquitous Londonisation: “a process usually bringing financial enrichment while impoverishing local distinctiveness.” But looking ahead to May 2015, he predicts that “it is unLondon, in its infinite variety, that will decide the election.”

London’s response to such criticisms has often been a wounding indifference. Its flavour is reminiscent of the encounter in 1866 between the visiting Scots professor John Stuart Blackie and the renowned Balliol college head, Benjamin Jowett. “I hope you in Oxford don’t think we hate you,” said Blackie, to be told, “We don’t think of you.” An article published on 12 December suggests that this might be changing. In it, the Financial Times’s senior political commentator Philip Stephens draws a different moral from the national misalignment, namely that “London should break free from Little England”:

London does not need a mayor; it needs a prime minister. Britain is fracturing. Scotland may yet quit the union and England turn its back on Europe. The Conservatives are throwing up barricades against the immigrants who are the capital’s lifeblood… This is a moment to imagine a different future: independence.

The vision comes complete with border controls (“the M25 orbital motorway is the readymade frontier”), a federal constitution, membership of the European Union, and openness to skilled immigrants. For Stephens, who on the day of Scotland’s referendum described the “heart of the nationalist case” as “the politics of grievance and identity, of a nation done down by foreigners,” London’s adversaries are domestic.

Doubtless, the pinched English nationalists of [UKIP, the United Kingdom Independence Party] and anti-immigration pressure groups would cry foul. Tant pis. Their vision of statehood, fixated on the proportion of the population that is “white,” is confounded by London’s success. Saloon bar bores in the home counties can be left to their anguished debates about identity. Londoners should break free.

No prospectus of the United Kingdom’s future, whatever its starting point or sympathies, seems able to accommodate its capital. Londoners’ own instincts, as much as their interests, revolt at the thought of a country governed by the embittered nativists of UKIP. For their part, leading pro-independence Scots such as Lesley Riddoch strain every intellectual sinew to associate these two groups. Anti-Londoners such as Danny Dorling can barely contain their rage against the city, as if its very existence is an offence. Fashionably lurid dystopias of the city abound, from the macho ultra-leftist China Miéville (in the New York Times) to the Russia expert Ben Judah (in Standpoint).

London can take it all. But it is hardly surprising that a good number of Londonists are being provoked into writing their own script, in some versions of which the city turns from dumpee to dumper with Nixonian relish: “you won’t have London to kick around anymore!”

Across the great divide, there is ever more distrust and caricature than empathy and curiosity. London and much of the nation are increasingly strangers to each other. A compelling example of how the gulf can operate arrived on 19 November, the eve of a by-election in Rochester & Strood, an estuary constituency in north Kent, thirty miles east of London (thus well within commuting distance, and with a mixed social profile). The sitting Conservative member, Mark Reckless, had defected to the meteoric UKIP, pledging to regain the seat under his new colours and thus emulate the example of Douglas Carswell, who had become UKIP’s first MP by the same route in September. In the event, and despite strenuous Tory efforts, he did so, albeit with a diminished majority that could be vulnerable in the general election.

But UKIP’s qualified triumph was overshadowed by an incident on the last afternoon of campaigning, sparked by a tweet posted by the Labour MP and shadow attorney-general Emily Thornberry, who had joined the party’s desultory canvassing. (Labour held the seat 1997–2005, and in Nashaubah Khan it had the most impressive candidate by far, yet third place was the height of the party leadership’s ambition.) The tweet showed the a plain residence with a white van parked outside, bedecked with two large and one smaller English flags – the red “St George’s cross” against a white background. It was coyly captioned “image from #Rochester.”

Robert Doisneau it was not. Not even Martin Parr, documentarist of prosaic English life. In other hands, in other circumstances, in other times, it might have seemed innocuous. But in this instance, the who, what, when and how of the image-tweet ensured that by tea time its author was at the centre of a media–political firestorm. And by then, there was no room for doubt about its why. Snobbery, it seemed, was the only possible motive: an instinctive disdain for the kind of patriotic working-class household that had once been the backbone of Labour’s support but which the party had now abandoned. A Labour MP during an election would once have knocked on Dan’s door – his name, the world soon learned, along with the colour of his toothbrush, was Dan – and sought his vote; now she regarded his domain with, at best, an anthropologist’s curiosity. Click, tweet, pass on. Goodbye, Dan. Farewell, Labour.

What clinched the outrage was that Emily is a prosperous, middle-class London lawyer, who – with peerless congruity – represents part of Islington (more exactly, the constituency of South Islington & Finsbury). This is the area of London that came to signify New Labour’s modernisation of the party in the mid 1990s, and the network of progressive, confident and super-salaried professionals most associated with the process. Moreover, the Englishman’s castle she snapped was not in historic Rochester but in Strood, the more workaday (and, as if it mattered, once Labour-voting) part of the constituency. Emily hadn’t even clocked precisely where she was.

Britain loves nothing better than a row about class, especially when it comes with a twist of toxic prejudice. This one was almost too perfect. By now – and it was still only mid evening – a single synapse on its way to Emily Thornberry’s dendrite seemed to encapsulate Britain’s entire post-1945 history in a way that David Kynaston’s thousands of pages couldn’t hope to emulate.

There was more to come. The late evening news shows were reviewing the epic events of the day when they found themselves reporting it. Labour’s leader, Ed Miliband – his aides spinning that they had “never seen him so angry” – had sacked Thornberry from the shadow cabinet. The act, both purgative and self-protective, amplified rather than defused the sense of crisis around Labour. Ed dug deeper the next day when he was asked what went through his mind when he saw a combination of house, white van and England flag. The correct political answer, which Groucho Marx’s four year-old child would know, is: “A hard-working guy who supports the England football team.” A tiny pause as Ed rifled his files. Then: “Respect… the first rule of politics is that you respect the voters.” It sounded like another line from the anthropologist’s playbook.

By next morning, Thornberry, on her way to parliament, was delivering a spare apology in the accepted modern style (for “any offence caused”) to reporters besieging her Islington townhouse, where Dan – signed up by the Sun – was soon pictured draping an English flag across the railings. The Sun’s involvement seemed further to confirm the precision of the story’s entire script. Rupert Murdoch’s flagship tabloid – still Britain’s largest seller, even if circulation has dipped under two million – had made “white van man” a shorthand for the kind of independent, straight-talking and proudly English-British figure that was close to its ideal reader. The phrase, as so often with the British media and advertising industry’s dragnet sociology, was both widely adopted (as badge of pride or convenient daub) and soon supplemented (in this case with associations of racism, sexism and illiberalism).

In the media lifecycle of the tweet that launched a thousand columns, the contrast between “white van Dan” and snooty Emily was a gift. Every other outlet played its part, with the Daily Mail providing a helpful guide to the lucrative north London lairs of Labour’s upper crust, and all the papers measuring the chasm between it and the party’s traditional base. More discomforting thoughts were kept in check. For one, that Dan might not at all symbolise the “natural Labour voter” (Lauren Fruen, the smart Sun reporter who bonded with him and his partner over football and their overlapping roots in east London, found he didn’t know a by-election was happening); for another, that Emily Thornberry’s own world might be more than a cultural stereotype.

Thornberry often refers to her own upbringing in a council estate near Guildford, southwest of London, by her mother following her parents’ divorce. Her brother Ben, himself an enterprising all-rounder who drives a (red) van, was unearthed, confirmed the picture and defended big sis against the charge of snobbery. More interesting was that he also referred, as had Emily in her first response to criticism before the storm fully broke, to the “weird” stereotyping of Islington. It’s not a cause likely to win followers outside the pages of the Islington Tribune, yet that itself is reason to dwell on it. After all, “Islington” is as much a media construct as “white van man,” the pair forming – as Kenan Malik writes in a well-judged New York Times piece – polar opposites in Britain’s political iconography. And cases like Thornberry’s, though rarer now that the sun has set on the New Labour era, show that the easy engulfing of Islington by “Islington” still has potency.

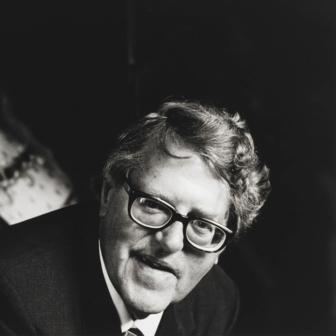

It used to be that leafy Hampstead, next to the eponymous heath in northwest London, was the catch-all signifier for Labour dottiness or left-wing excess (as in “Hampstead liberal” or – fetch the crucifix and garlic! – “intellectual”). The high, or low, point of the formula was probably the press pursuit of Michael Foot during the chaotic election campaign in 1983, when the sixty-nine-year-old Labour leader – with his stick, thick glasses, disobedient white locks, and dog Dizzy (named after the nineteenth-century Tory prime minister Benjamin Disraeli) – took his morning constitutional on the heath.

Foot was, admittedly, a Hampstead socialist-liberal-intellectual brought to life – though even here, scruple requires mention that he was a resident of Highgate village, to Hampstead’s northeast, beside the eponymous cemetery where Karl Marx and other luminaries are buried, and a place with quite its own character. A reminder is in the title of the local paper, the Hampstead & Highgate Express, the much loved “Ham & High.” That’s the trouble with – or the beauty of – London. It’s granular, ever-reducible, with cultural borders (as well as other types) on almost every turn.

The “Hampstead” twitch made a rare appearance days before the Thornberry affair, when Jason Cowley, editor of the venerable New Statesman – founded in 1913 by the Hampstead-dwelling Fabians, Sidney and Beatrice Webb – broke from his and the weekly magazine’s benign view of Ed Miliband by branding the current Labour leader “very much an old-style Hampstead socialist.” The article echoed the case made over several years by specialists in Milibandology – notably the pungent Dan Hodges of the Telegraph – but the resulting furore suggests that this jibe too still carries a sting (and worse, argues David Cesarani in the Jewish Chronicle, a stigma).

The shift from Hampstead to Islington in the media “imaginary” of Labour and the left derives from an over-egged account of a restaurant meeting in 1994 between the rising Labour stars Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, days after the sudden death of John Smith, the Scots lawyer who had become Labour leader only two years earlier. Their agreement that Blair, the junior partner, would stand for the succession, is regarded as the semi-formal birth of New Labour, which would sweep to power in 1997. Again as so often, a more or less arbitrary designation flashed into life and then withered into a hand-me-down, the connection to what happened at Upper Street’s Granita restaurant vanishingly remote.

Islington, long before then, had been used to slights, if the poem that prefaces John Nelson’s 350-page history, published in 1811, is a guide. (“Old Iseldon, tho’ scarce in modern song, / Nam’d but in scorn…” – though it goes on to praise the then village’s health-giving waters). The media’s modern identification of Islington with a privileged Labour elite may equally amount to less than a hill of beans in Britain’s crazy political world. It would be hard to identify any material harm the “scorn” has inflicted. Except perhaps to occlude the fact that Islington is a real place where actual people live, which happens to be as interesting and diverse as most in London or beyond. It is also, like all the London boroughs around it – Camden, Hackney and Lambeth, among thirty-two in total – a focus of belonging for its residents, who on the whole exist along the same spectrum as those of any other city in Britain. (In 2011, they numbered 206,000, 45 per cent of them "white British," including 4000 Scots and 1200 Irish). Nor is it inordinately rich, even if the wealthy there are in the top bracket: in fact, across a range of social indices, Islington is the thirteenth-poorest borough in England and Wales.

This difference between Islington and “Islington” struck me forcibly a decade ago during another brief media-political uproar. Boris Johnson, then editor of the conservative Spectator magazine, had published a crass and inaccurate column – drafted by Simon Heffer in polemical mode – criticising, inter alia, the “flawed psychological state” of “many Liverpudlians” in relation to the Hillsborough tragedy of 1989, when ninety-six football fans died in a pre-match terracing crush. The BBC’s flagship morning radio program interviewed the Liverpool Echo’s editor, who lambasted the apologetic Johnson, justly condemned stereotyping of the northwest city – and along the way, took various swipes at those who traduce Liverpool’s good name at “Islington dinner parties” and “posh Islington restaurants.” The interviewee’s unawareness of his own inverted snobbery (or snobbery tout court) was matched by the BBC interviewer’s indulgence of a puffed-up non-metropolitan voice.

Trivial in itself, the episode was a reminder that social prejudice feeds off laziness of thought and language, and that the warping potential of class in Britain requires an ever vigilant eye. Being anti-“Islington,” or Londonphobic, or any variety thereof, I remember thinking, is the socialism of fools. Many external depictions of London today – more concerned with “othering” than understanding, with flattening than discriminating – have the same bad smell. No political good can come of them.

My own Islington (and London) patriotism evolved over a decade, and was forged by a passionate attachment in particular to two points at either end of Islington’s winding trajectory: Clerkenwell in the south, where I worked, and Archway in the north, where I lived – the former for its richness of history and associations, the latter for its all-inclusive humanity. Clerkenwell, hiding in plain sight on the edge of the City – where Chaucer delved, Samuel Johnson scribbled, Chartists orated, Dickens observed, Fenians bombed, Lenin plotted, Lubetkin designed, Italians settled, watchmakers and jewellers crafted, and dissidents of every hue gathered – is inexhaustible. Archway, huddling beneath its infamous early 1960s tower at the tip of that “river of metal,” the Holloway Road, is elusive in a different way. Not even its mother would call Archway beautiful. But stay, mingle, tune in – not least to the voices, from Ireland, Turkey, Poland, Zimbabwe and all points beyond – and its pulse of life is generous.

Islington’s local history museum and centre, now based in Clerkenwell, are the best resource for learning about this fascinating area across centuries of change. But Archway is a good place to see that change struggling to renew itself: in the housing schemes planned around Junction Road, the efforts of the Better Archway Forum, the campaigns to protect Whittington hospital, the innovative art projects, the burgeoning street markets, the local library’s outreach (and the story of libraries in Archway was itself a project by the artist Lucy Harrison), the Archway with Words literary festival, and plans to develop the tower (or just to make it disappear). Life in Archway, as across London, is tough for very many. But again like the rest of London, it’s a neighbourhood where tolerance and familiarity are everywhere. You can’t be a stranger long in Archway – partly because so many before you started out as just that.

Archway’s experience of “regeneration,” convulsive and modest by turn, has several cycles to go. (It is, after all, the place where the immortal Charles Pooter, in the Grossmith brothers’ Diary of a Nobody, published in 1892, “struggled to live a life of middle-class propriety.”) Here as everywhere the much abused process is a complex interplay in which people’s confidence and agency can be enhanced as well as eclipsed. The very pace of recent change in London, to people’s neighbourhoods and working lives, on and beneath the surface, produces many-sided reactions, of which one is an even stronger affinity with primary social units. Everywhere in London people are researching and writing histories of their street, their locality, their borough, collating information and oral testimonies, laying on exhibitions, as well as creating autonomous arts colleges and educational projects (such as Hackney’s Open School East) that self-consciously belong to a particular area and seek to tap into its currents.

Several books published in recent months alone – The Gentle Author’s Spitalfields Life, Martin Plaut and Andrew Whitehead’s Curious Kentish Town, Rose Rouse’s A London Safari: Walking Adventures in NW10, and Julian Mash’s Portobello Road: Lives of a Neighbourhood – are examples of this broad trend. They draw on the same energies that are fuelling Londoners’ desire for more self-government. In principle, these energies underline London’s affinity with developments elsewhere in Britain. But without an appreciation of this fact, and in the absence of any process that can connect disparate regional–national ambitions, mutual distance grows.

Many Londoners want devolution both to their city from the UK state, and to more local levels from city-wide government. Such aspirations are becoming a factor in the debate over Britain’s constitutional future. It would greatly elevate public debate were they, and London's distinct political realities, accorded equal respect with their equivalents in non-London. Today, reductive views of London are a weapon of stupidity against democracy. They are also self-defeating, since there is so much for everyone to learn in the experience of this infinite yet intimate city. •