If life had turned out the way Sydney University honours student Mike Pezzullo intended, then he would be a renowned historian rather than the public servant in charge of Australia’s hotly contested border protection regime. “From very early on I was fascinated by history,” says Pezzullo. “So I absolutely wanted to be a history professor.”

History doesn’t run in straight lines, but nor is it totally disjointed. Pezzullo imagined a future writing books about the history of warfare and strategy, but instead built a career in the portfolios of defence, foreign affairs, customs and immigration helping to craft national security strategy. If his star keeps rising, he will play an even broader role in creating history of the sort he once hoped to write about, as head of the powerful new home affairs ministry, which will oversee Australia’s intelligence agencies.

Pezzullo, who currently heads the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, is far too discreet a public officer to comment on possible assignments. “It’s not in keeping with etiquette to canvass, discuss or speculate about the appointment of secretaries,” he says. The prime minister’s announcement of a new home affairs ministry is still a few days away when we meet; if Pezzullo knows about it, he gives me no hint.

We talk over lunch at an Italian restaurant in Belconnen. “Thanks for coming all the way out to Canberra’s far north,” he jokes when he arrives. The venue is close to his office, and he describes it almost apologetically as “modest and suburban” but offering “very flavoursome food.” He is right on both counts. A neighbouring barn-like pub dwarfs the low-slung Bella Vista, and from the barren carpark the prospect of a beautiful outlook seems remote. Inside, however, floor-to-ceiling windows provide a panoramic view of the wintery landscape of Lake Ginninderra.

Pezzullo’s choice of restaurant matches the heritage of this Australian-born son of migrants from rural Campania, outside Naples. In 1960, his father was determined to leave a country still waiting for a postwar recovery to take hold. He chose Australia over rival destinations Canada and Argentina because his sister had already settled here. But Pezzullo’s mother was reluctant to move so far away from her parents, and went to live with siblings in Manchester. After two years of long-distance courtship, she was convinced to join her teenage sweetheart in Sydney. Once married, they settled close to his relatives in the St George area in Sydney’s south, where Michael, the eldest of three sons, was born in 1964.

“It is a typical migrant story,” says Pezzullo. His parents had little education and no formal qualifications, he tells me. His mother was pulled out of primary school at the age of six to care for a newborn sibling; she returned to school after about six months, but when she was nine she had to leave permanently to help out at home. His father never completed high school. They did unskilled and semi-skilled work, labouring on building sites and in factories and gardens, often holding down two or three jobs at a time. At home, the family spoke a mixture of Italian dialect and English. “We were spoken to in Italian but we were encouraged always to respond in English,” says Pezzullo. “It was the same with all my cousins. And our parents were very strong on that. This is our home. We speak English here.”

Pezzullo was urged to maintain his cultural heritage but regard himself as Australian. “Mum and Dad would say, ‘This country has given us everything. We owe this country everything.’” At school, he learnt to ignore insults of “wog” and “dago,” which, he says, were like “water off a duck’s back.” There was no malice in the jibes, he says, though he adds that it “wasn’t funny at times and it certainly wasn’t done in a nice way.”

Pezzullo was raised as a Catholic and went to Catholic schools, but now attends an Anglican church with his wife Lynne, who grew up in a Protestant family. Lynne Pezzullo is another influential Canberra player, providing extensive advice to government as the lead health economics and social policy partner at Deloitte Access Economics. The couple has four children.

Last year the Canberra Times ranked them at number four on a list of Canberra’s top ten power couples, but some of the other media coverage that Pezzullo has received has been less flattering. Former Australian Financial Review columnist Tony Walker recently described him as “a ruthless political operative,” while milder-mannered colleague Michelle Grattan labels him “an aggressive bureaucratic player.” ABC political correspondent Andrew Probyn says Pezzullo is seen in Canberra as “an extraordinarily hard-working, driven and intelligent fellow” who is “admired and loathed in unequal proportions.” He sums him up as “brilliant but divisive.”

If Pezzullo has an abrasive side then it is not on show as we break bread in Belconnen. He is friendly, engaged and solicitous, topping up my mineral water, inquiring about my food. (Our grilled barramundi is perfectly cooked and very reasonably priced.) He doesn’t deliver pronouncements while staring into the middle distance in the manner of some top bureaucrats I’ve met, instead leaning in to listen, making eye contact and responding thoughtfully.

His comments also reveal that he is a keen reader, especially in the area of military history and strategy. A recent speech to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute was peppered with references to such works: the first volume of Niall Ferguson’s biography of Henry Kissinger (Kissinger, 1923–1968: The Idealist), Paul Dibb’s study of the Soviet Union (The Incomplete Superpower) and the writings of early twentieth-century strategists Alfred Mahan, Halford Mackinder and Nicholas Spykman.

Pezzullo tells me this interest began early. Around the age of ten, he would play with massed groups of toy soldiers “always configuring them for battle.” He avidly watched the 1973 British documentary series The World at War and by his early teens was reading anything he could get his hands on about the great battles of the second world war — the attack on Pearl Harbor, D-Day, Operation Barbarossa. His preoccupation was not encouraged at home. “Mum remembered the war and said you never want to go through a war,” he says. “She hated the war.” The family’s only connection with the armed forces was his father’s compulsory military service in Italy, a box that had to be ticked.

Nor was it a bookish family. Pezzullo says his parents could only read and write “to a limited extent.” They encouraged scholarship but primarily as a means of getting ahead. Their view was that reading books was a necessary precursor to a professional career. They didn’t want their son to labour for a living like they had. While his parents assumed that their diligent teenager was poring over books that would help him become a doctor or an engineer, he was instead devouring information about strategy, and trying to understand how the second world war started, what Churchill’s plan of action was, and how America’s approach to the conflict evolved. “Then I branched out a bit with the first world war,” he recalls, “and similarly tried to deconstruct how nations found themselves stumbling into wars, how they can be prevented, what the strategies are for getting out of wars.”

In the early 1980s, Pezzullo felt he had found his calling studying European history and historiography at the University of Sydney. But Richard Bosworth, renowned historian of Italy, steered his bright honours student away from the academy, telling him it offered few jobs and poor career prospects. Instead, he encouraged Pezzullo to consider a more secure future in government service.

It is hardly surprising that the firstborn son of working-class migrants would feel pressure to seek a stable job with good prospects for advancement. In Pezzullo’s case, an extra consideration was in play. His mother was now a widow, bringing up her sons alone. In 1983, at the age of forty-six, Pezzullo’s father had taken his own life. “Mum had done it pretty hard,” he says, “so getting a job was important.”

Pezzullo was just eighteen years old at the time. He reveals enough for me to glimpse the distress associated with his father’s rapid and unexpected mid-life descent into illness. “I always remember he was very muscular, very strong, because he laboured all day,” says Pezzullo. Over two years, as he went in and out of psychiatric institutions in the antiquated support systems of the day, his father lost both his physical health and his self-esteem. “This was a very proud, hard-working man, physically very fit, and to see him hit a wall so he couldn’t work, couldn’t hold down a job… it was very difficult.”

In 1987 Pezzullo joined Defence as a graduate. But his career in government has not been a standard climb through civil service ranks; he has achieved a rare trifecta, working not only at the highest level of the public service but also as a top adviser to a senior government minister and a lead staffer to an opposition leader.

In 1992, after five years in Defence and a stint in Prime Minister and Cabinet, Pezzullo left his public service position to join the office of foreign minister Gareth Evans. This was not a “political appointment” in the way that term is understood today. “In those days, it was standard, especially in the foreign minister’s office, to have public servants fill the role of what were traditionally called private secretaries,” he says. “So you didn’t come up out of the party.” Most ministers in the Hawke and Keating government had a strong complement of public servants in similar roles, he says, “moving the papers, making sure that the minister has everything he needs contextually to come to a decision.” Other people in the electorate office dealt with party business and it was “very unusual” to have political officers on ministerial staff.

Pezzullo’s work for Evans was guided by some golden rules: “Never shape the advice, never filter the advice and never withhold it from the minister.” I ask him if these rules are observed today. “No comment,” he responds with a grin. But it is unfortunate, he has told politicians on both sides of the house, that the demarcation of duties has blurred. “You are never going to have a completely hard separation, because in the minister’s mind the policy, the politics, the ideology, the platform, the program, the activities, they all ultimately have to come together,” he says. But he thinks the traditional Westminster separation of private secretaries from party concerns should be maintained to the extent possible, so that they can focus on administration and policy.

“In today’s environment, where the media cycle is just revving at such a rate, the time for administration is quite rapidly being sucked out,” he says. “So you have to create time and space around the minister. The good ministers — and I’ve been blessed to work for a number of them on both sides of politics — fight hard to create that time and space for proper administration, considering certain issues, meeting with their senior public servants to go through options, commissioning new options, getting intelligence briefings, and the like.”

After John Howard led the Coalition to victory in the 1996 election, Pezzullo continued working for Gareth Evans in opposition. Then he became deputy chief of staff to Labor leader Kim Beazley, running his office and advising him on national security. It was a meeting of like minds: “Colleagues pretty quickly worked out this is not going to be helpful because these two are just going to be constantly talking about either the [American] civil war or military technology or the second world war or whatever,” he laughs.

Pezzullo rejoined Defence after Labor lost the 2001 election. He had formed a personal and professional bond with both Evans and Beazley, he says, but he didn’t see himself as “a political animal.” If Beazley had won the 2001 election, though, things might have been different. “If Kim had become the prime minister and had asked me to stay on in some capacity as a national security adviser, I would have very favourably considered that,” he says.

In “policy and intellectual terms,” the most fulfilling experience of Pezzullo’s public service career so far was writing the 2009 defence white paper under Kevin Rudd. He was excited to have the space “to deconstruct defence strategy and policy” and to conjecture in a rigorous way about the strategic circumstances Australia would face in the future. His warning about the possibility of a conventional war at sea was not widely accepted at the time. “Regrettably, it’s proved to be prophetic,” he says.

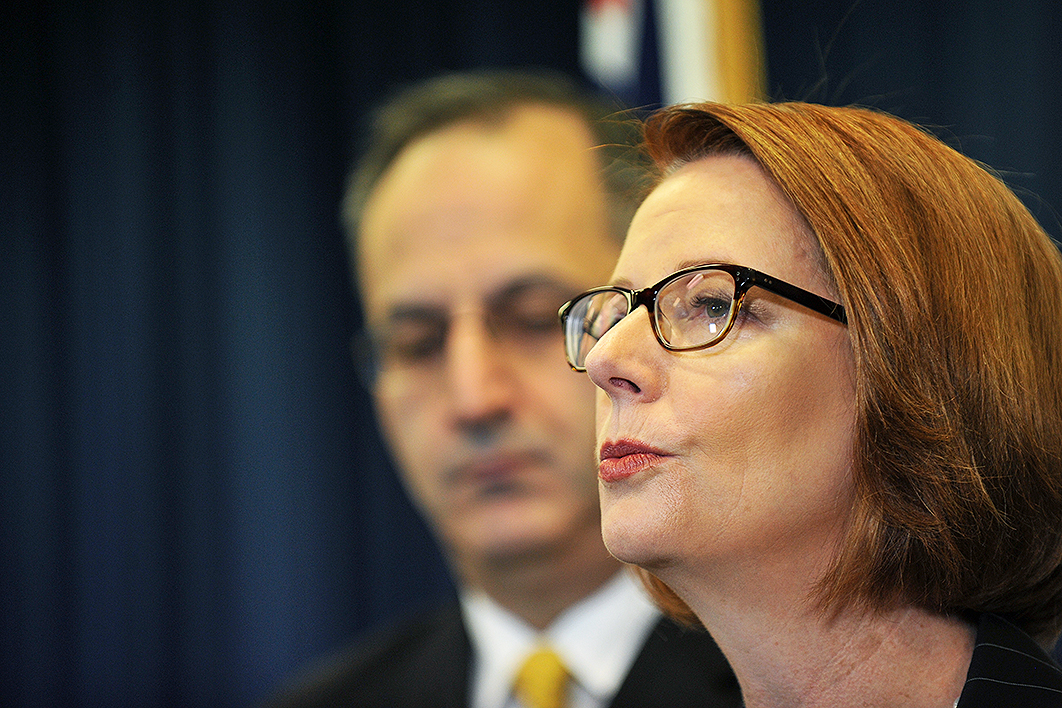

Prime minister Julia Gillard answers questions during a press conference in March 2013 with Mike Pezzullo, who was then the CEO of Australian Customs. Paul Miller/AAP Image

While assembling the white paper connected with Pezzullo’s lifelong interest in the history and strategy of warfare, the “more emotionally and personally fulfilling” part of his job as departmental secretary is leading teams, something he would never have done as an academic historian. So the high point of his career aligns with his controversial and contested role in “stopping the boats”: oversight of Operation Sovereign Borders, with its offshore detention centres, turnbacks and temporary protection visas.

At this point in our discussion, Pezzullo is at pains to ensure that he is not misunderstood. “I don’t want any suggestion that Pezzullo was thrilled by supporting Abbott or something,” he says. “I’m not talking about the political dimension, that’s between the politicians to argue about. And I’m not even speaking to the discourse around managing refugee policy.”

Satisfaction came from rising to the demands of the assignment he was set. “It was a challenging strategic and operational problem to deal with because the flow of boats was just unrelenting,” he says. “The fulfilment factor… was really about how you harness a dozen or more agencies to execute the plan.”

The role of “a responsive public servant,” says Pezzullo, is to think “conceptually and intellectually” about how to implement the policies of an incoming government. Discussing the “work in progress” that is the merger of immigration and customs, he says that public servants at his level should be able to manage changes almost irrespective of the content. He draws an analogy with industrial relations in the Howard era: “As one of my colleagues says, as a good professional public servant, you have to be able to both create WorkChoices and then, when the government changes, dismantle WorkChoices.”

Yet Pezzullo has been accused of stepping beyond his role as an independent public official to become “a muscular protagonist” in the hotly contested debate about refugee policy. In early 2016, for example, he famously told Senate estimates that “no amount of moral lecturing” by advocates would bring forth solutions to the plight of refugees detained for years in Manus and Nauru.

A strong policy thread certainly runs through Pezzullo’s career. In 2001, during a federal election campaign dominated by the September 11 attacks and the Tampa affair, opposition leader Kim Beazley promised to set up an armed Coast Guard “fully integrated into our nation’s intelligence and surveillance network” within a new “powerful, cabinet-level Ministry of Home Affairs.” Mike Pezzullo was Kim Beazley’s national security adviser at the time.

Veteran Canberra-watcher Malcolm Farr credits Pezzullo with providing “the aggressive energy” behind the armed and uniformed Australian Border Force created in the merger of Customs and Immigration (or, as critics would have it, the “hostile takeover” of the larger entity by the smaller). Dennis Atkins, another experienced press gallery journalist, says Pezzullo has long urged his political masters “to reorganise the border force, domestic intelligence and policing functions into a United States style Homeland Security set-up.”

In a follow-up telephone call, I ask Pezzullo whether he takes any credit for the intellectual and strategic impetus to create a new ministry of home affairs. “None at all,” he replies. “It was the prime minister’s decision.” The same is true of the policy Labor took to the 2001 election, he says: it was Beazley’s policy, not Pezzullo’s. He insists that he is not ducking my question. The job of public servants is to provide advice in a robust and contestable fashion, but elected officials own their decisions.

What if a public servant has serious ethical or moral concerns about a policy? I ask. Having worked closely with five prime ministers at secretary or deputy secretary level since 2005, Pezzullo says senior public servants have every opportunity to raise whatever concerns they may have, without any fear of repercussions. If, after having been heard, the final decision is one the public servant still cannot accept, because it contravenes a deep personal conviction, the public servant has no choice but to resign. “I have not had to contemplate resigning,” he adds.

As we tuck into our fish, I ask Pezzullo how he regards the deeply held views of the 30 per cent or so of Australians who find the government’s border protection policies morally unacceptable.

“I respect their right to not only oppose the policy, but to express their dissent as they see fit within the law,” he says. “I mean, the whole point of preserving your sovereignty is to allow the diversity of expression and opinion.”

But does he regard them as misguided or naive?

“No, I would never use pejorative terms like that.” He insists, though, that opponents of the bipartisan policy of offshore detention and boat turnarounds must face up to two problems: “the death rate problem” and “the rationing problem.”

To illustrate, he begins with an interpretation of the Refugee Convention that obliges signatory countries to assess the claims of all asylum seekers who reach their territory and to allow them to stay if they need protection. That’s “a perfectly valid view to at least put into the argument,” he says, but it becomes problematic when you “operationalise” it. Why? Because it builds “a supply chain of movement,” he argues, in which “non-state actors” become the intermediaries between the place of persecution, the final destination and all points along the way. While some intermediaries have honourable motives, he says, many are criminals focused only on profit.

“I can’t think of any other policy areas where you would design in the space and the scope for criminals to say, okay, I can move people,” he says. Cutting the people smugglers in, says Pezzullo, inevitably means some people will die. A conservative estimate of 1200 deaths at sea during the arrival of around 50,000 asylum seekers by boat under the last Labor government produces a death rate of about 2.5 per cent. That is not the intent of policy settings, says Pezzullo, but it is the outcome, and that can never be acceptable to any government.

He recognises that there is an alternative response to the problem: set up a government-based solution that cuts out the people-smuggling intermediaries. In other words, organise “planes, cruise ships, whatever” to go and pick people up. But this raises his second concern, “the rationing problem”: how many people do you rescue?

“What is the limit?” he asks. “If you ration it at fifty thousand, when the fifty thousand and first person arrives, what do you do then?” He is convinced that if Australia were to organise airlifts of refugees from, say, Indonesia, then countless more asylum seekers would seek to travel the same path. With sixty-five million people displaced from their homes around the world, including twenty-one million refugees outside their national borders, there is no obvious upper limit to the number of people who would seek Australia’s help.

The way forward, he believes, has three stages. First, deal with the reasons why people flee their homes in the first place. “Now Syria, that’s difficult,” he says. “In East Africa, the South Sudan, people pouring into Kenya, I get all that, but we can’t disconnect this from the Security Council, what Gareth Evans famously in his book called ‘peace building.’ That whole agenda just has to be constantly attended to.”

Second, protect people in place — either in their homelands or in neighbouring countries. Again, Pezzullo acknowledges the difficulties: safe-haven strategies in response to the war in Yugoslavia and the genocide in Rwanda foundered on rules of engagement that prevented peacekeepers from using their weapons to protect unarmed civilians. Pezzullo knows that the real burden of global displacement is borne by countries of first asylum like Turkey, Lebanon, Pakistan and Kenya. He says the international community needs to find ways to support people who flee into neighbouring countries until it is safe for them to return, and this means enabling them to work, raise a family, educate their children and get access to healthcare for a decade or even longer.

Finally, says Pezzullo, governments around the world need to offer more places to those in urgent need of permanent resettlement in a third country. There are around one million people on UHNCR’s books ready to be resettled, but only about 100,000 places available annually.

Australia is pursuing these objectives, he says, as part of the global compact initiated by the September 2016 special UN General Assembly session on refugees and migrants. He is cautiously hopeful that the process may eventually produce positive results. But as the world currently stands, critics who want to dispense with the bipartisan policy of offshore processing and boat turnbacks must address the twin problems of the death rate and rationing. “I think that there should be a respectful, clinical discussion, and if people can solve that conundrum, we should adopt the view of the 30 per cent or so that you describe in your question.”

Our allotted hour is up, but I squeeze in one last question. If changes currently before parliament were in place in his youth, I point out, then his parents, with their limited literacy, might never have met the English-language requirements necessary for citizenship. (Pezzullo has spoken elsewhere about memories of his parents’ earnest discussion about the significance of making a full commitment to Australia.) He won’t discuss the substance of the bill, but he reassures me that the government will make appropriate exemptions and create supports for refugees or people with learning difficulties.

He also believes that the context has changed. In the 1950s and 1960s, Australia was seeking unskilled and semi-skilled workers to build its population. “Did you want to see signs then of, not their assimilation, but their integration?” he asks. “Yes, absolutely. Was it happening organically? I can tell you it absolutely was.” In those circumstances, there was no need for government to concern itself with English-language testing. Today, in a service-based, high-skills economy, when migrant communities remain intimately connected to their homelands by modern communications, “it’s a different world.” •

The assistance of the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund in providing funding for this article is gratefully acknowledged.