Health policy wonks around the world are nervously watching the attempts of the yet-to-be-installed Trump administration and the new Republican-dominated Congress to make good on their commitment to dismantle Barack Obama’s signature healthcare reform legislation, the Affordable Care Act. So keen are congressional Republicans to see “Obamacare” repealed that they’re pushing ahead even before Donald Trump’s inauguration.

On this issue, they’ve had plenty of practice. The House of Representatives voted some sixty times during the last Congress to abolish Obamacare in whole or part. Republicans were saved from the consequences of these votes by the difficulty of getting the legislation through the Senate and, ultimately, by Obama’s veto power. Now we’re about to see the full impact of this desire to destroy Obama’s legacy as they proceed with the “first order of business” of the new administration.

But is it possible to uproot wide-ranging reforms embedded in the nation’s healthcare system without irrevocably damaging the system as a whole, and the iconic Medicare and Medicaid programs? Can it be done without disenfranchising the estimated twenty-three million people who have gained health insurance and the millions more who have benefited from its provisions? And can congressional Republicans implement this dogma when it doesn’t necessarily match the views of the new president or the people who voted for him (and for them)?

The situation is further complicated by the fact that, despite the rhetoric of “repeal and replace,” there is no consensus about what any substitute healthcare reforms would look like, and how and when they would be implemented.

Health policy experts of all persuasions agree that any delay in introducing a coherent and comprehensive replacement (which assumes agreements from all stakeholders, including Democrats) will cause havoc in insurance markets and among hospitals and healthcare providers, and incite anger in the population, with Trump supporters among those most likely to be adversely affected. Obama, outlining his concerns about repealing but not replacing Obamacare in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, has called the Republican plans “reckless.”

Leadership will be key, but Trump and his senior staff have presented a multitude of conflicting positions, many of which don’t sit well alongside those of Republican speaker Paul Ryan and Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, or of Trump’s own nominee for the position of health and human services secretary, Tom Price.

By one count, Trump has changed his position on Obamacare eight times since announcing his bid for the presidency, and this is probably an underestimate. His official campaign policy, released in March 2016, is just four pages of the usual Republican boilerplate, with no accompanying detail. The plan includes proposals for individual health savings accounts (a form of self-insurance), sales of health insurance across state lines (states regulate insurance; this is a poor substitute for the insurance marketplaces or exchanges established by Obamacare), high-risk pools to provide insurance for people with pre-existing conditions, and the conversion of federal funds for Medicaid into block grants to the states, enabling them to spend funds as they wish. According to the non-partisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, this plan would see twenty-three million people lose their health insurance and cost at least US$350 billion over the next decade.

Trump himself has made statements across the gamut of conceivable positions, including some that are directly opposed to Republican orthodoxy and his own official policy. He has praised single-payer systems like those of Canada and Scotland. He has said “I like the mandate” and “I don’t want people dying in the streets.” And he has indicated he would be open to amending Obamacare instead of a full repeal.

He has promised many things, including “Everybody’s going to be taken care of much better than they’re taken care of now” and “You’ll have competition, you’ll have so many different plans.” He has pledged to keep protections for those with pre-existing conditions and to retain the measure that allows parents to keep their children insured until they are twenty-six. And he committed to no gap between repeal and replace, boasting to CBS’s 60 Minutes: “We’re going to do it simultaneously. It’ll be just fine. That’s what I do. I do a good job. You know, I mean, I know how to do this stuff. We’re going to repeal it and replace it. And we’re not going to have, like, a two-day period and we’re not going to have a two-year period where there’s nothing. It will be repealed and replaced. I mean, we’ll know. And it’ll be great healthcare for much less money.”

Given his campaign rhetoric, Trump must be seen to do something about Obamacare on day one. His vice-president, Mike Pence, has said, “We are working on a series of executive orders… to ensure there is an orderly transition… to a market-based healthcare economy,” but has given no indication as to what these might encompass. They will likely be more symbolic than real.

Meanwhile, Republicans in Congress aren’t paying much attention to what the president-elect wants. Despite a warning tweet from Trump, they are already taking action to repeal, with a replacement delay that could be years. Their strategy relies on the use of the budget reconciliation process to fast-track the legislation. (It would require only a simple majority to pass in the Senate, where it must originate, protecting it from filibustering.) But there are serious constraints: the process can only involve measures that have a direct and measurable impact on spending and revenue, and it allows for unlimited amendments.

The Senate and the House of Representatives both hope to pass a budget resolution before the inauguration. This will require the four committees that control health policy (Energy and Commerce, and Ways and Means, both in the House; Finance and Health, and Education, Labor and Pensions, both in the Senate) to draft legislation that would cut at least a relatively small $1 billion from the budget over ten years. The committees will have until 27 January to produce a legislative package repealing the major provisions of Obamacare.

These provisions are likely to include eliminating tax penalties for individuals without healthcare insurance and larger employers who don’t provide cover for their employees (thus undermining the mandate for universal coverage), repealing subsidies for purchasing insurance through the exchanges (which will reduce affordability), and withdrawing federal funds to the states to cover Medicaid expansion (which will deprive many low-income people of insurance). The committees could also repeal some of the taxes and fees (on health insurers, manufacturers of pharmaceuticals and medical devices, and some very high-income individuals) that help pay for Obamacare, but they may need this money to apply to deficit reduction and/or any replacement legislation.

One example of the smoke and mirrors games that will be played is a small provision in the House rules package passed last week that specifically exempts the repeal of the Affordable Care Act from the usual ten-year cost analysis in an attempt to conceal the cost to taxpayers.

Budget reconciliation legislation is always a vehicle for a raft of extraneous amendments, and Paul Ryan has already given notice that this time around Republicans will seek to defund Planned Parenthood, an organisation that provides essential women’s health services, including birth control, screening for breast and cervical cancers, and testing and treatments for sexually transmitted diseases. Planned Parenthood is demonised by conservatives because it provides abortion services, although strict guidelines (restated in the Affordable Care Act) prohibit the use of federal funds for this aspect of its work.

Many aspects of Obamacare can’t be dealt with in the budget reconciliation package because they don’t have a direct and measurable budgetary impact. These include protections for individuals with pre-existing conditions, the prohibition on lifetime and annual reimbursement caps, risk insurance pools, various changes to Medicare, and provisions that relate to prevention, public health, the workforce, healthcare disparities, and quality and safety.

The Republicans are saying they will delay the effective date of repeal (periods of up to four years have been mentioned) to avoid disruption and – because they have no viable option ready to go – to allow time for the development of alternatives. A lot of damage could be done in that time and, as Trump has warned, Republicans will wear the blame. Democrats can run interference and make their own case to the American people; public rallies can protest loss of benefits; hospitals will face increasing costs for uncompensated care; and the marketplace will be disrupted by uncertainty.

Republicans will need to act to prevent a healthcare meltdown that will damage the federal budget (the Congressional Budget Office estimates that full repeal would increase the deficit by US$137 billion over 2016–25), cost jobs (the Milken Institute estimates three million jobs, one-third in healthcare, will be lost in 2019), seriously affect state budgets (Milken estimates a cumulative US$1.5 trillion loss in gross state products if replacement policies are not in place, and a US$2.6 trillion reduction in business output in 2019–23), and will result in more people, mostly those who are already sicker than average, going without care (one estimate is that an additional 8400 people will die every year).

It is ironic, given the nature of the recent election campaign, that the debates in Washington about the repeal and replacement of Obamacare are very disconnected from what voters who supported Trump want – although what they want is often unclear or contradictory. The blue-collar Americans who supported Trump have been the main non-minority beneficiaries of Obamacare, which they say they oppose. Americans only understand (and like) Obamacare through the prism of their own experience and many among the increasing number of beneficiaries are nervous about seeing these benefits vanish.

Recent focus groups conducted with Trump voters in the rust-belt states of Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania revealed that the main concern is cost – rising premiums, deductibles and co-payments, and unanticipated medical and pharmaceutical expenses. Many of these non-college-educated white voters have found purchasing insurance through the new exchanges “hopelessly complex” and see people on Medicaid as getting a better deal. They don’t see Obamacare as a universal program that provides an earned benefit like Medicare or Social Security; they see it as analogous to food stamps or welfare, and fear that less-deserving people are getting more benefits.

These voters are unmoved by the principle of risk-sharing inherent in mandatory insurance, which they view as “un-American,” but they see the proposals like health savings accounts and tax credits, championed by Republicans, as “not insurance at all.” They trust Trump to look after their interests, but they don’t know what he will do and are worried about what happens next. They may well find GOP alternatives even less attractive, and much more expensive, than Obamacare.

The real problem may lie with the Republicans themselves. They all bought into the rhetoric that Obamacare is socialism, a job killer, a government takeover – an endless drain on the federal budget that “just doesn’t work.” They fell for the idea that healthcare will be better and less expensive as soon as Obamacare is repealed. But they have never looked beyond the slogans to the facts and the dollars. And they didn’t use their time in opposition to develop an alternative.

Members of the House Freedom Caucus (essentially the Tea Party) are suddenly jittery, threatening to block passage of the budget resolution over fears it might keep Obamacare taxes in place. And on the other side of the Capitol, at least six Republican senators are not on board the repeal-and-delay train. Moderate Maine senator Susan Collins is making the case that law-makers should, at the very least, release a detailed framework of their plan to replace Obamacare before repealing the law. Only then can Americans, especially those who depend on the law for their coverage, and the insurance industry know where they are headed. The situation will only get more fraught when substantive policies (with costs attached) are up for debate and enactment under procedures that require sixty votes for passage in the Senate.

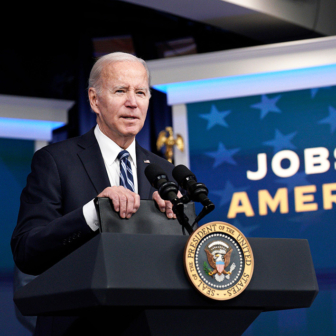

In an interview last week, Obama succinctly summed it up: “And now is the time when Republicans have to go ahead and show their cards… There’s going to be a massive undoing of what’s one-sixth of our economy [and] the Republicans need to put forward very specific ideas of how they are going to do it.” He said that he had advised Trump to “make your team and the Republican members of Congress come up with things that they can show will actually make things better for people.”

In that interview and in his New England Journal of Medicine paper, Obama outlined two key things that need to be borne in mind by those planning changes to the reforms he is proud to call Obamacare: “These are real lives at stake” and “First do no harm.” Will these drive the Republicans’ reforms? •