Peter Capaldi’s Doctor Who re-enters the universe groping and spluttering. He has trouble recognising his companions from the Tardis, confuses genders and species, doesn’t understand the purpose of a bed or a bedroom. “What’s gone wrong?” he cries.

A spot of memory trouble, it seems. Understandable at the start of a reincarnation — though now that the Doctor Who series has passed its fiftieth anniversary, memory might also be an issue for the audience and the program’s creators. Viewers of different generations will remember the Doctor’s previous incarnations in different ways, and fans who have formed a deep attachment to a particular actor will have to be won over by the newest incumbent. Some will remain nostalgic for Patrick Troughton or Tom Baker. Others, not even born during those eras, may still be engaged in a virtual romance with the spunky Christopher Eccleston, the funky but dashing David Tennant or the quirky Matt Smith, each of whom has been a seriously hard act to follow.

Does there come a point when the fans, like the Doctor himself, start to suffer from memory overload? The so-called “Rings of Akhaten” speech from series seven is something of a theme statement and has become a set-piece in its own right. It is widely distributed on the internet, and was delivered live by Matt Smith at the 2013 Doctor Who Prom concert. Akhaten is a planetary dictator who feeds off the experiences of his people by consuming their memories – until the Doctor issues a challenge that scares him clean into the next galaxy:

Come on then! Take mine. Take my memories. I hope you’ve got a big appetite, because I’ve lived a long life and I’ve seen a few things.

I saw the birth of the universe and I watched as time ran out.

I have seen things you wouldn’t believe. And I know things – secrets that must never be told. Come on then – take it – take it all baby! Have it. You have it all.

I don’t remember in what circumstances I heard the news of President Kennedy’s assassination, but I have a perfectly clear recollection of where I was the following day, 23 November 1963, when I saw the inaugural episode of Doctor Who. As a twelve-year-old, I’d recently moved with my family from a sprawling Adelaide suburb to a cramped house in Oxford, where a damp and gloomy autumn was about to turn into one of the severest winters on record. With the nights drawing in early, my parents finally gave in to a long-running campaign for the acquisition of a television, which was delivered that afternoon. Doctor Who was the first thing we watched.

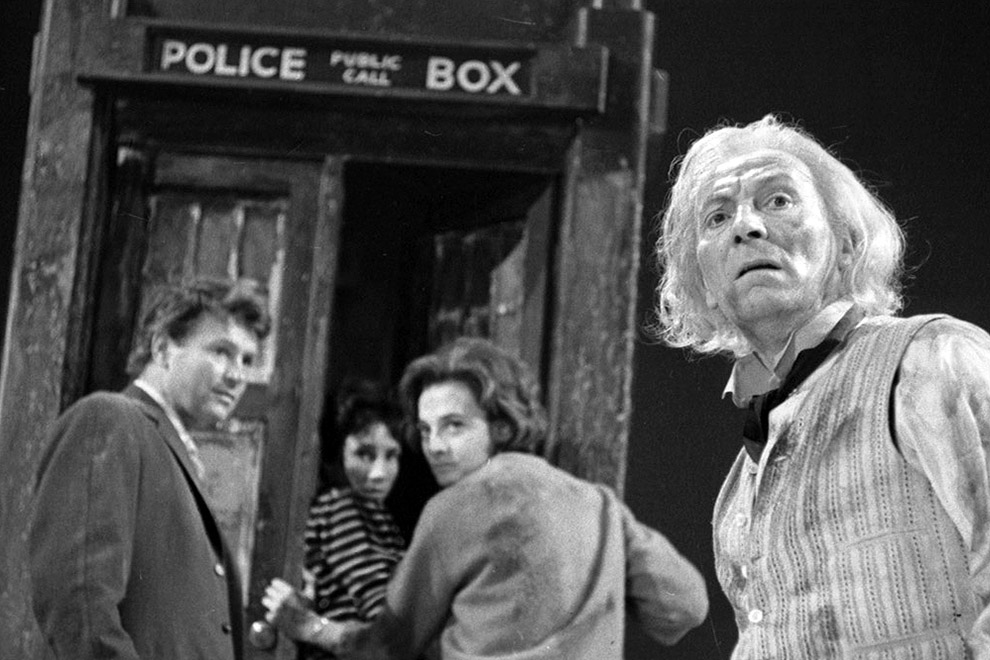

“An Unearthly Child” is the title of that story, which can now be seen on YouTube. It begins with a policeman doing his rounds on a misty night, checking out a junk yard by torchlight and bemused at the presence of a police phone box amid the jumble. It’s somewhat out of place, though curiously rather than freakishly so, and a touch sinister, especially as the camera pans across the silhouettes of abandoned department store dummies.

Phone boxes were installed for public safety, we should remember, and were part of the streetscape in English towns of the 1960s. The public ones were painted red and had glass-paned walls so that you could see in (a measure that did not always serve to discourage what was known as “hanky panky”). But the blue police boxes with their high set frosted windows were impenetrable to the gaze of passers-by. It was a stroke of genius to exploit their mystery, especially by suggesting that what was inside them was very much more than the apparent sum of their external parts.

When two prying school teachers – one a science master at the local grammar school – manage to gain entry to the Tardis, they are outraged by the logical impossibility. The Doctor, played as a testy Victorian patriarch by the white-haired William Hartnell, has no patience with their questions. Surely they are familiar with television – a small box that contains all manner of scenes and landscapes? A half century ago, when old technologies were new, this was an arresting observation. Now the televisions of that time, like the telephone boxes on the street, are dinosaurs.

In one of its many flashes of sly wit, the launch episode for the latest series, “Deep Breath,” opens with a dinosaur quite literally vomiting up the Tardis, sending it spinning in an arc across central London. The dinosaur is an anachronism rather tortuously worked into an overstretched plot set in the Victorian era, but anachronism is a deliberate and subtle game compared with the spectacle of full-on cosmic time warping. Wisely, Stephen Moffat, the writer of the episode, seeks to draw us back into the over-familiar world of the Doctor through carefully paced story-telling rather than an electronic blitzkrieg from the special effects department.

Scripting has been one of the strong points of the Doctor Who enterprise from the outset. Australian writer Anthony Coburn wrote the script for “An Unearthly Child,” balancing the sci-fi ingenuity of the production with some carefully spun narrative tension between the characters, and a nice instinct for the uncanny. It’s not an easy balance to sustain, though many of the most successful storylines over the years – most notably those involving the sinister “weeping angels” – have been those in which traditional elements from the ghost story come to the fore.

One of the hallmarks of the uncanny in literature, as Freud observed, is the attribution of life and purpose to an inanimate object. The stone angels that move when you are not looking are a classic example. It’s an effect that works best when you’re not expecting it, and as we now expect pretty much anything in Doctor Who, it’s subject to the law of diminishing returns. Very few of the ideas generated in the script room have produced anything genuinely scary on screen, and the malevolent angels are less scary with every reappearance. I’m sure we’ll see them again in the new series, but it will be a challenge to get any chill out of them. “Deep Breath” does achieve a moment of genuine frisson, though, when the very human-looking diners in a sedate restaurant reveal themselves as automata, making a noise like the whirring of finely engineered clockwork as they converge on the Doctor and Clara to prevent them leaving.

To add to the dramatic tension, these pseudo-beings have sniffed out the Doctor as a certain kind of fellow traveller. In the preceding scene, Capaldi has been scrambling around in a Victorian nightshirt, turning over the rubbish in an alleyway, evidently looking for something. Himself. He finds a mirror and inspects the face he is wearing but doesn’t understand it. There are frown lines, yet he didn’t do the frowning. The cold reminds him that he needs something to wear. Unlike his predecessors, who were birthed in a fully conceived image with expert assistance from the wardrobe department, this one is a lost soul in search of both image and identity. He tries to enlist the help of a passing tramp, and swaps his watch for the old man’s coat and gloves.

In the restaurant, the Doctor tears the prosthetic face off one of the automatons, and invites Clara to try it on. The automatons are traders in body parts, working to rebuild identities they have lost or never had. But they will kill for theirs. They belong to the succession of enemy species the Doctor must work to defeat. Who or what is he, then, in this conflict? Clara, too, is having a crisis. She doesn’t know who he is any more either.

It’s a good premise for the new series, which promises to be more narrative driven and less flashy than the last. Capaldi and his sidekick Jenna Coleman are already looking like an adroit double act, exchanging repartee at a cracking pace, with a behavioural dialogue that adds to the volatile dynamic.

The show’s producers have been challenged repeatedly about the continuing pattern of using a female character as a support role for the Doctor, and however hard they push the girl-power buttons in the storylines there is still some real ambiguity about their commitment to shifting the gender stereotypes. The edgy verbal delivery at which Coleman excels is counterpointed by a lot of cutesy facial expressions, along with a visual image reminiscent of a sixties dolly bird. Capaldi is a brilliant choice for the new Doctor, but isn’t it time they tried someone other than a white Anglo-Saxon male in the role?

At least he is allowed to give free reign to his Scots accent. David Tennant had to suppress his. In the 1960s and 70s, the occupants of the Tardis always spoke the King’s English, and watching the vintage episodes is a reminder that the original story belongs in a science fiction tradition that sets the British against a lot of weird looking aliens who really shouldn’t be trusted to inhabit any the planet, even if it’s their own home ground. For all its ingenious narrative and thematic evolution, I’m not convinced that old Dr Who story isn’t still lurking in the background. •