David Gonski is a famously cool customer, but surely even his sangfroid was tested as he rose to speak on Wednesday evening at Melbourne University’s Wilson Hall. This was his first substantial public statement since the release of the eponymous report on schools funding more than two years ago, years of incessant headlines, of hopes raised and dashed, and of bitter political brawling. He was entering dangerous territory.

The “Gonski” review was launched by the Rudd/Gillard governments at the point of intersection of three of the most enduring conflicts of Australian political life: between federal and state governments, between left and right, and between the free, secular government school sector and religion-based, fee-charging non-government schools. All ride on the tectonic plates of class and class relations, slow-moving but fundamental.

“Gonski” argued that these divisions have allowed the school system to drift steadily towards greater social segmentation, and have prevented it from tackling persistent problems of inequality. Overcoming these problems, the review suggested, demanded overcoming these divisions. All public funding for schooling, federal and state alike, should go into a single national bucket from which each school would be funded according to the difficulty of its educational task, irrespective of its location or sector.

The divisions declined to be overcome, however. “Gonski” was first hung out to dry by its sponsor, the Gillard government, then passionately embraced; watered down before being accepted by some states and rejected by others; rejected then embraced then tolerated for the moment by the federal Coalition in the person of Christopher Pyne; and, most recently, confronted by a counter-proposal.

The National Commission of Audit, after finding arrangements left in the wake of Gonski to be “complex, inconsistent and lack(ing) transparency,” has recently urged the new government to abandon the national bucket in favour of a devolved approach – give the money to the states, that is, for their use and distribution within a broad national framework.

What, in the light of all that, would this courteous, quietly spoken master of the backrooms of power, this chairman of everything, choose to say? He had promised to define “the essence of the findings of the review,” to consider whether and how these findings had been understood and implemented, and to close with some remarks on what he learned from being involved in the review. Plenty of scope there.

Would he play the statesman, perhaps? Accept that the end of greater fairness in schooling might be served by means other than those that he and his panel devised? Some version of the Audit Commission’s model, for example? That would alienate Labor as well as making it seem that he had reverted to corporate type, not a man of principle at all, just another player in the cynical game.

Or fight fire with fire? The temptation was certainly there, in Pyne’s brazen opportunism, and in the Commission of Audit’s arch interpretation of “Gonski” as just another funding mechanism. A payback killing might keep faith with Gonski’s many supporters and his Labor’s sponsors, but it would also enrage a federal government with a long memory. It would obliterate any hope of influencing the Abbott government’s eventual solution.

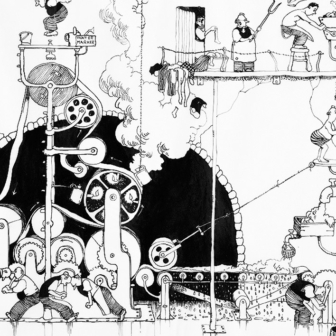

Or might he, just might he say what he really had “learned from being involved in the review”? That Australian schooling is squandering its patrimony, becoming more socially divided and less able to deliver on the promise of “equal opportunity” by the minute? An ungovernable mess, buzzing with activity but making scarcely any headway? That its world’s-worst-practice three-sector system is a divisive relic of the nineteenth century? That the blame-shifting involvement of two levels of government in every school in the country is counterproductive? That having governments on three-year electoral cycles run a business that needs big strategies pursued over decades is a recipe for muddle, frustration and waste?

No, he didn’t say those things. But nor did he say anything to the contrary. He is a subtle man, used to saying things with silence.

What he did say, out loud, was that he apologises for nothing and regrets nothing – well, one small thing perhaps. It might have been better, in the light of experience, not to have mentioned the price tag. “Major media outlets,” he observed, naming no names, “talked of further billions for education and no doubt those who had to find the amount were very bluntly reminded of what was involved.”

The shame of that was that it distracted from the real point and purpose of the report, the breadth and complexity of problems it took on: big differences in funding amounts and methods between states and sectors; the fact that those least in need had most, and vice versa; the opaque, complex and various ways of measuring and allowing for disadvantage; the lack of clear statements of “aspirations” for schooling. “Two years on… our analysis has stood up to scrutiny,” said Gonski. “Some may disagree with aspects and conclusions but I’m not aware of any major holes that have been found.”

Gonski was warmly welcomed by a big crowd and even more warmly farewelled – he made it clear that this was his “postscript” – but was only once interrupted by applause, and that was when he insisted that the purpose of a funding system was to “ensure that differences in educational outcomes are not the result of differences in wealth, income, power or possession.”

At that and many other points Gonski took tacit issue with Margaret Thatcher’s famous dictum that there is no such thing as society. He reported his own family’s debt to schooling. He talked about the “enormous” difference between “well-endowed schools and those in the lower socioeconomic areas.” He insisted that many of his peers in the world of big business shared his “feeling for society.” He encouraged people to work outside their home territory. “It is good for the individual [and] good for the society” because it builds “trust and cooperation” between sectors.

He attacked as well as endorsed and defended. His chief target was the Commission of Audit. Its alternative scheme might be clear and simple, but “like a lot that is simple it is not adequate.” States could not be both custodians of their own schools and responsible for funding competitors. In any event, leaving things to the states could lead to different systems and different aspirations in different parts of the nation. The Commission’s argument for winding back spending increases planned for 2017 and beyond was to be regretted. If money had to be saved, why hadn’t the Commission revisited the previous government’s decision that “no school will be worse off”?

Gonski told his audience that the review presented him with an “opportunity to make a stand.” His speech was another, and he took it.

Is that entirely a good thing? Gonski’s speech, like his report, reflects rising concern around the Western world that the surge of wealth to the already-wealthy over the long postwar boom has become a threat to social cohesion and to the legitimating claim that “opportunity” is “equal.” Social cohesion and legitimacy are core business for schooling. We should certainly be grateful that Gonski called for a national approach to schooling in the social as well as the geographic and political sense.

It is an approach that should have national appeal, especially coming as it did from the big end of town. There is nothing inherently sectional or party-political about it. A conservative government could find as many reasons to go along with it as a Labor administration, and as Gonski himself pointed out, the most enthusiastic “Gonski” supporter has been the Coalition government in New South Wales.

Its federal counterpart, however, is of a very different mind, and not merely in the service of Christopher Pyne’s ever-changing political needs. The underlying dynamic is that members of privileged groups often use privilege to pursue immediate individual interests at the expense of the long-term stability of the social order on which their privilege depends.

That is exactly what the high-fee independent schools have been encouraging their clients to do in the golden decades since Gough Whitlam launched an education spending bonanza in response to Peter Karmel’s Schools in Australia report. Burgeoning wealth has allowed them to just about guarantee the transmission of cultural capital from one generation to the next, partly through success in academic competition, partly via what would in other circumstances be called social engineering – using fees and academic selection to cherry-pick students and families, and to constitute networks, outlooks and codes. In the process, these schools and their selective companions in the government sector have performed something like the inverse of that service for excluded social groups and their schools.

In this perspective, Gonski (Shore old scholar) and fellow panellist Kathryn Greiner (chair of high-end Loreto Kirribilli) can be seen as reminding their peers that schooling has tasks and responsibilities that go beyond privileging their own offspring. And Pyne can be understood as saying: you gotta be kidding – enjoy!

Pyne has prevailed, thus far at least, because problems of social cohesion and legitimacy are not (yet) as marked in Australia as in some other societies, notably Britain and the United States, and because he and his Coalition colleagues are blinkered to Gonski-like concerns by their own experience of privilege and by an ideology that reflects it. They find it easier to see individuals as masters of their fate, and markets as the arena of their fair and bracing competition, than to see that both depend on a coherent social order accepted by its citizens as fair and legitimate.

In these circumstances it is not hard to see why David Gonski’s expression of a fundamentally different way of thinking about society and schooling would receive such a warm reception from his Wilson Hall audience. But there is a big distance between the impulse and its full articulation as policy and translation into practice.

“Gonski” was only ever one part of the jigsaw of a fully national approach to schooling. It was never even allowed to be a full review of funding. Its terms of reference took as given Australia’s unique and uniquely dysfunctional three-sector system – some pay, some don’t, and so on ad infinitum. “Gonski” recommended funding floors, but no ceiling, leaving those who can to pay whatever it takes to thwart equal opportunity. “Gonski” had much more to say about the distribution of funding than its effective use. It is now, after two years as a political football, weaker in all these respects.

One of the central obstacles to a fully national approach is the so-called “residualisation” process, alluded to above. As the Gonski review and one of its commissioned reports show in close detail, well-positioned schools – in all three sectors – do whatever they can to attract the “best” students and their families, thereby both excluding the rest and undermining the schools that they do have access to. Levelling-up the funding field is a part of the answer, but so is doing something about the rules and conventions of the game. On these, Gonski’s terms of reference were silent.

Problems of design are compounded by problems of political engineering. The hard fact is that “Gonski” did not get up. The Gillard and Rudd governments tried to get nine governments to pull in the same direction, and Gonski’s proposals depended on their being able to do so. They couldn’t. That failure follows the failure of Whitlam’s Schools Commission, established in 1973 to prosecute a national approach but dead within a decade, victim of states and non-government systems jealous of their prerogatives.

The apparently paradoxical lesson may well be that the Commission of Audit’s devolution scheme, muscled-up to include targets for and monitoring of schools’ social composition, income and expenditure, value-add, and quality of learning experience as well as the “outcomes” nominated by the Commission, is more likely to achieve Gonski’s objectives than the mechanisms proposed by the review.

The great danger now, particularly for the Labor Party, is that it will venture once more unto the Gonski breach. Unfortunately, Gonski’s remarks did little to encourage Labor to think twice, and Bill Shorten probably wouldn’t be listening anyway. His budget-in-reply speech suggests that he can scarcely believe his political luck. He can go to the next election as the man who will deliver Gonski.

For those with long enough memories there is an awful feeling of déjà vu all over again. Gonski’s oration was in honour of Jean Blackburn, the philosopher queen of Australian schooling for two decades or more. Blackburn was a highly influential member of Whitlam’s Karmel Committee. It, too, wanted a “national” approach in the social as well as the geographic and political sense, a schooling system that honoured the social contract. It, too, was the hope of the side.

As some of Jean’s intimates know, she was worried sick, right from the start, that the alignment of political forces was such that “Karmel,” despite having the right impulse, was constructing the wrong machinery. Far from settling the “state aid” question, as Whitlam boasted, she feared that it was being put on a new, complicated, inherently unstable and heavily defended basis. As a prominent figure in Australian education with important work to do as the Schools Commission’s guiding intellectual light, she was hardly in a position to say so. Later, she was.

“There were no rules about student selection and exclusion, no fee limitations, no shared governance, no public education accountability, no common curriculum requirements below the upper secondary level,” Blackburn wrote in 1991. “We have now become a kind of wonder at which people [in other countries] gape. The reaction is always, ‘What an extraordinary situation.’”

The resulting mess is what, forty years later, Gonski was asked to deal with. Unless we are very lucky, and in particular unless Labor is prepared to do some difficult and rapid thinking, someone will be saying something very like that about Gonski in another forty years’ time. •