Labor and the Coalition are united on border control. Both are committed to turning boats back to Indonesia, Sri Lanka or any other country they may have set sail from. If boats evade naval patrols, make it to Australian territory and can’t be returned, then Bill Shorten and Malcolm Turnbull are equally adamant that the asylum seekers on board must be packed off to detention in Manus or Nauru. Both sides insist that people already being held offshore, who have been there almost three years, will never come to Australia, even though close to 1500 of them have been recognised as refugees. Both major parties have ruled out using the only other viable resettlement option, New Zealand.

The Manus detention centre has been found to be unconstitutional and must close; the PNG government says refugees can settle in the country if they choose, though few want to. Nauru has made it clear that refugees can’t remain permanently on its territory. Bill Shorten might have promised to redouble efforts to find alternative resettlement places, but the reality of the Labor–Coalition unity ticket is that neither side has the faintest idea of where these refugees might go.

To justify the policy of offshore processing and turnbacks, both parties resort to the realist language of necessity. When recycled prime minister Kevin Rudd announced shortly before the last election that no one arriving by boat after 19 July 2013 would settle in Australia as a refugee, he described the measure as “hard public policy… which must now be implemented.” It was a “practical step forward,” he said, and would be taken “calmly, rationally and with resolve.” Australians might have “kind and compassionate” hearts, but we would accept the policy because we also have “hard heads.” In other words, we must focus entirely on the result we are seeking and ignore (or suppress) any niggling emotions that might prompt us to discuss the ethics of the process we use to get there.

Turnbull used remarkably similar arguments during the 2016 election campaign. On Q&A, responding to a contractor’s description of the situation on Manus – “It is terrible the way they treat the people there. They are treated worse than animals” – he acknowledged that the policy was “harsh” but insisted that it was necessary because “the alternative is far worse.”

“None of us have hearts of stone,” the prime minister added, while insisting that the situation requires us to behave as if we do. To resettle refugees from Manus and Nauru in Australia would be, he says, “the biggest marketing opportunity for the people smugglers you have ever seen.” They would exploit our “weakness” and the “boats would be setting off again.” The consequence would be “women, children and families drowning at sea.”

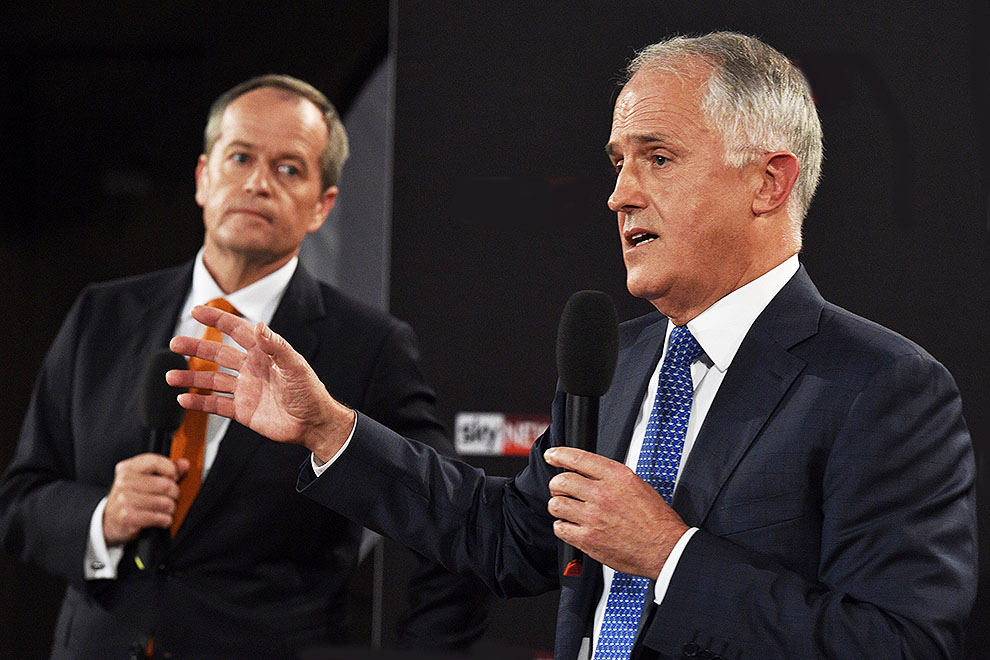

Labor’s policy differs slightly from the Coalition’s. It would abolish temporary protection visas and open up Manus and Nauru to journalists. But in the first leaders’ debate during the campaign, Shorten was eager to show that he and Turnbull were essentially one. “We would defeat the people smugglers,” he said. “We accept the role of boat turnbacks, as we should, because we don’t want to see the people smugglers back in business.”

While the emphasis shifts, both leaders give essentially the same reasons for why we must be tough: to defend the integrity of our borders, save lives at sea and defeat the smugglers. On Q&A, Turnbull added keeping children out of detention to the list. In his time as immigration minister, Philip Ruddock claimed that harsh policies were needed to shore up public support for an orderly migration program that might otherwise be overwhelmed by a xenophobic Hansonite backlash.

Regulating movement across borders, combatting people smuggling, saving lives at sea, keeping kids out of detention and countering racism – all these are legitimate aims of public policy. Indeed we might say that policy-makers are obliged to act to realise such aims. Problems arise, though, when we are told that there is only one realistic, hard-headed way to do this, and when leaders insist that moral questions are an unwelcome and unhelpful distraction from the necessary task of achieving a practical solution.

“No amount of moral lecturing from those who seem unable to comprehend the negative consequences of an open borders policy will bring forth those solutions,” immigration department head Mike Pezzullo told Senate estimates in February 2016. “All that can be done is being done,” he insisted, with reference to the search for resettlement places beyond Australia and New Zealand. Pezzullo suggested that to deal in the real world of necessity, we must be wary of giving expression to feelings like empathy. “Yielding to emotional gestures in this area of public administration simply reduces the margin for discretionary action which is able to be employed by those people who are actually charged with dealing with the problem.”

The famously hard-headed Scottish Enlightenment thinker Adam Smith, best known for his description of the invisible and indifferent hand of market economics, might argue otherwise. He regarded empathy (or sympathy, as he called it) as the fundamental human emotion, crucial to our capacity to establish norms of behaviour that enable us to live together cooperatively. For Smith, emotion (“immediate sense and feeling”) rather than reason is the source of our “first perceptions of right and wrong.”

Defenders of Australia’s system of border control would say that this is an area of public administration that must be quarantined from such troublesome moral sentiments. A hard head can’t be combined with Smith’s soft heart. We must do what is necessary.

In his discussion of just and unjust wars, political philosopher Michael Walzer argues that the word “necessary” enfolds two meanings – inevitable and indispensable. To say that something is inevitable is to accept that it could not be otherwise; it is the outcome of forces beyond our control, like a natural disaster, or an event that we could not possibly have anticipated because of our ignorance of essential facts. We can only decide if something was inevitable with the benefit of hindsight. To describe an action as indispensable, though, is to make it contingent on some particular outcome; it is to assert that A is necessary (indispensable) in order to achieve B. And this kind of argument is always open to challenge.

Walzer discusses this issue with reference to the Melian Dialogue in Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War (a text Turnbull also likes to reference). The Athenian representatives argue that it is necessary (indispensable) to invade the island of Melos in order to maintain and expand their empire. To allow Melos to remain neutral would show weakness and so invite other subjugated territories to rebel. With thirty-eight ships and 3000 soldiers waiting offshore, the Athenian “negotiators” tell the Melian leaders that they have no choice but to surrender. The Melians refuse to submit, and defend their stance with talk of what is right, rather than what is necessary. The Athenians respond by arguing that if the Melians had the upper hand, they “would be acting in precisely the same way.” The Melians are duly crushed.

The Melian Dialogue is the classic example of realism in international relations and a staple text in defence studies and foreign policy training. The thrust of the realist reading is that while we might clothe our actions in the language of justice, dignity and honour, when push comes to shove, it is interests and power that hold sway in international relations. Noble talk is just gloss. In the end, as the Athenians say, “the strong do what they have the power to do and the weak accept what they have to accept.” The dictates of realism and necessity draw a line under, or through, moral arguments.

The applicability of this doctrine to the policy of offshore detention and turnbacks is apparent. We are told repeatedly that there is no other way. Policy is instrumental in achieving one particular aim – stopping the boats – and the only valid measure of assessment is whether that aim is achieved. “You could say we have a harsh border protection policy, but it has worked,” a newly installed Turnbull told RN Drive in September 2015. “’I know it is tough, but the fact is that we cannot take a backward step on this issue.” There is no place for moral qualms or ethical discussion.

But, as Walzer points out, if “necessary” really means “indispensable,” then it should mark the start of a moral argument, not its end. He asks us to step back from the final, fateful dialogue between the Athenians and the Melians and consider what kind of debates may have taken place in the assembly in Athens some months earlier. Away from the front line, he contends, crucial questions of morality and strategy must have been in play. Will the destruction of Melos really reduce the risk to Athens from its client states? Might massacring the Melians in fact weaken the empire, since Athens will be seen as ruthless and tyrannical? Is it right to make an example of Melos to expand Athens’s imperial ambitions? Are there alternative policies that might achieve the same outcome without the same loss of life? Perhaps the questioning might have gone even further: is maintaining and expanding Athenian imperial power really a desirable aim in the first place?

With no known record of these discussions, Walzer admits that he can only speculate as to what was actually said. He does note, though, that Thucydides recorded an earlier debate about the fate of the Mytilene, who had broken ranks with Athens to ally with Sparta. The assembly first determined a collective punishment: all the men of Mytilene would be put to death and all the women and children enslaved. The next day, the assembly softened the decree. (“Only” a thousand ringleaders are condemned to die.) The amendment could be seen as “realist” in the sense that the assembly determines that massacring or enslaving the entire population might undermine the stability of the empire, but Walzer’s point is that (at least in Thucydides’s account) the citizens’ repentance and concerns about excessive cruelty cause them to revisit their original decision. “Moral anxiety, not political calculation, leads them to worry about the effectiveness of their decree.”

In other words, Walzer concludes, the destruction of Melos was not inevitable. It was a deliberate choice, and a different process of deliberation and a different choice were possible. The same can be said of our border protection policies; they too invite and require debate that draws on ethical principles as much as practical outcomes.

Some people might claim that what we do in Manus and Nauru can’t be described as punishment. People are safe from the persecution they faced in their homelands; they are fed and clothed and given shelter. This argument is unsustainable, and amounts to wilful ignorance, especially after the publication of Madeline Gleeson’s carefully documented book Offshore. To punish some asylum seekers in order to deter others is to treat people as means not ends, and so breach the Kantian categorical imperative that sits beneath contemporary conceptions of human rights.

We can ditch Kant and argue instead on the moral ground of utilitarianism – the greatest good for the greatest number or, to express it as Peter Singer does, doing all we can to minimise “avoidable pain and suffering.” We might argue, as many of our politicians appear to do, that the reduction of suffering achieved by preventing drowning at sea justifies any increased suffering caused by detention on Manus and Nauru. But such a crude calculus invites its own crude utilitarian rejoinder: might not the reduced suffering of displaced people who make it to safety counterbalance the increased suffering of those who die in the attempt? Hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers around the world appear to have drawn exactly this conclusion.

Any serious attempt to discuss the issue in utilitarian terms would require a more nuanced debate and a broader perspective. If our yardstick is the biggest possible reduction of avoidable pain and suffering, then we can’t focus solely on those displaced people who happen to come into Australia’s orbit; we must also consider what we can do to help the record numbers of people forced from their homes around the world.

I am not trying to suggest that there is an easy or obvious solution. To say that we should simply deal compassionately with those who manage to get here is to risk lives at sea and let the smuggling networks determine who gets protection and who does not.

My argument is that the real world and the moral world can’t be separated and that tough moral debate is a necessary part of the process of practical policy. If we incorporate moral considerations into our thinking, then we will have to work harder and think differently about our approach. This does not mean being impractical and indifferent to outcomes. Over the past four years, Labor and Coalition governments have spent billions of dollars vigorously pursuing deterrence through offshore detention; might the situation look different if similar energy and resources had been devoted to working with neighbouring governments to build a comprehensive regional protection framework?

If necessity rules our actions and realism is transcendent, then all discussion of justice is pointless and all talk of morals irrelevant. But this is not the case. Moral arguments have purchase; they are every bit as “real” as instrumentalist approaches and practical outcomes. Inconvenient as it can be to those in power, morality exists in the world (alongside strategic and other interests) and, as Walzer writes, “notions about right conduct are remarkably persistent.” That is why passionate concern about what happens on Manus and Nauru keeps returning to the surface: morality matters to us as human beings.

It is the capacity to make moral choices that allows us to describe ourselves as free beings. “Stand in imagination in the Athenian assembly, and one can still feel a sense of freedom,” writes Walzer, referring to the decision about the invasion of Melos.

Athens destroyed Melos when it was at the height of its imperial power. Thucydides’s history goes on to describe the subsequent naval expedition to Sicily, which ended disastrously for the Athenians. This turning point in the Peloponnesian war led to Athens’s ultimate defeat by Sparta.

So the real realist lesson may be this: when political leaders invoke the language of necessity, it is time to be on our guard. •