Australia has got superannuation policy wrong. The bipartisan plan to increase compulsory super contributions to 12 per cent will reduce wages today, do little to boost the retirement incomes of many low-income workers, and cost the federal budget billions now and well into the future. If politicians really want to help low-income earners, the planned increases should be scrapped.

The Super Guarantee works by forcing people to save while they are working so they’ll have more to spend when they retire. But it’s no magic pudding. As the Henry Tax Review and others have noted, higher compulsory super contributions are ultimately funded by lower wages, which means lower living standards for workers today.

This is more than just economic theory. When the Super Guarantee rose from 9 to 9.25 per cent in 2013, the Fair Work Commission’s minimum wage decision stated that the proposed increase was “lower than it otherwise would have been in the absence of the Super Guarantee increase.”

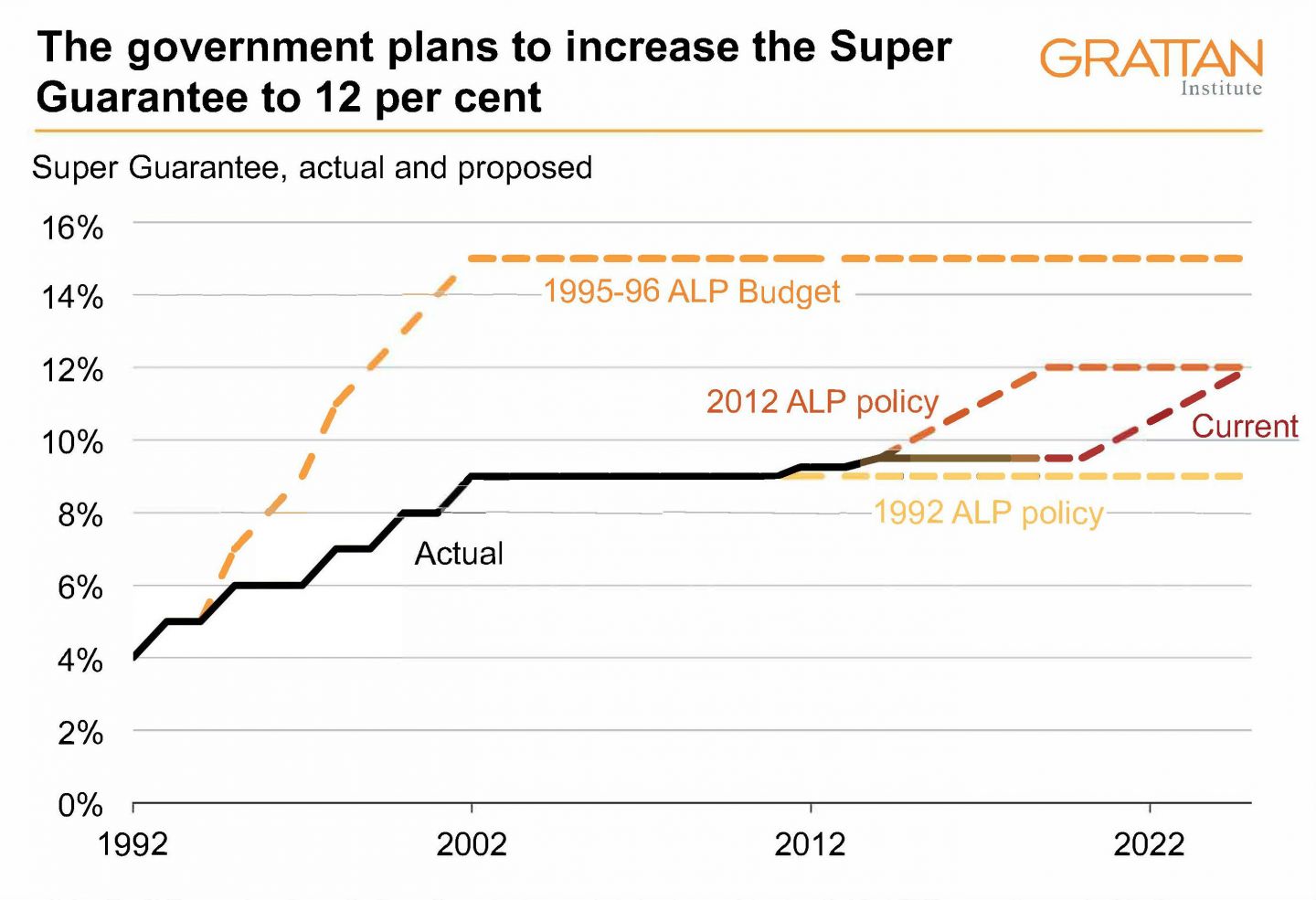

Sources: Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 as amended; 1995–96 Budget Speech; Labor’s Fairer Super Plan, April 2015

Yet the policy set in train by the Rudd and Gillard Labor governments means that the Super Guarantee will rise incrementally from 9.5 per cent of wages today to 12 per cent by July 2025. Tony Abbott’s government delayed the increases but stuck to the same goal.

The superannuation lobby argues that working Australians need more super to fund a reasonable retirement. But the truth is that current levels of compulsory super contributions, along with non-super savings (such as shares, bank deposits and interests in businesses or investment properties) and the age pension, are likely to provide a reasonable retirement for most Australians.

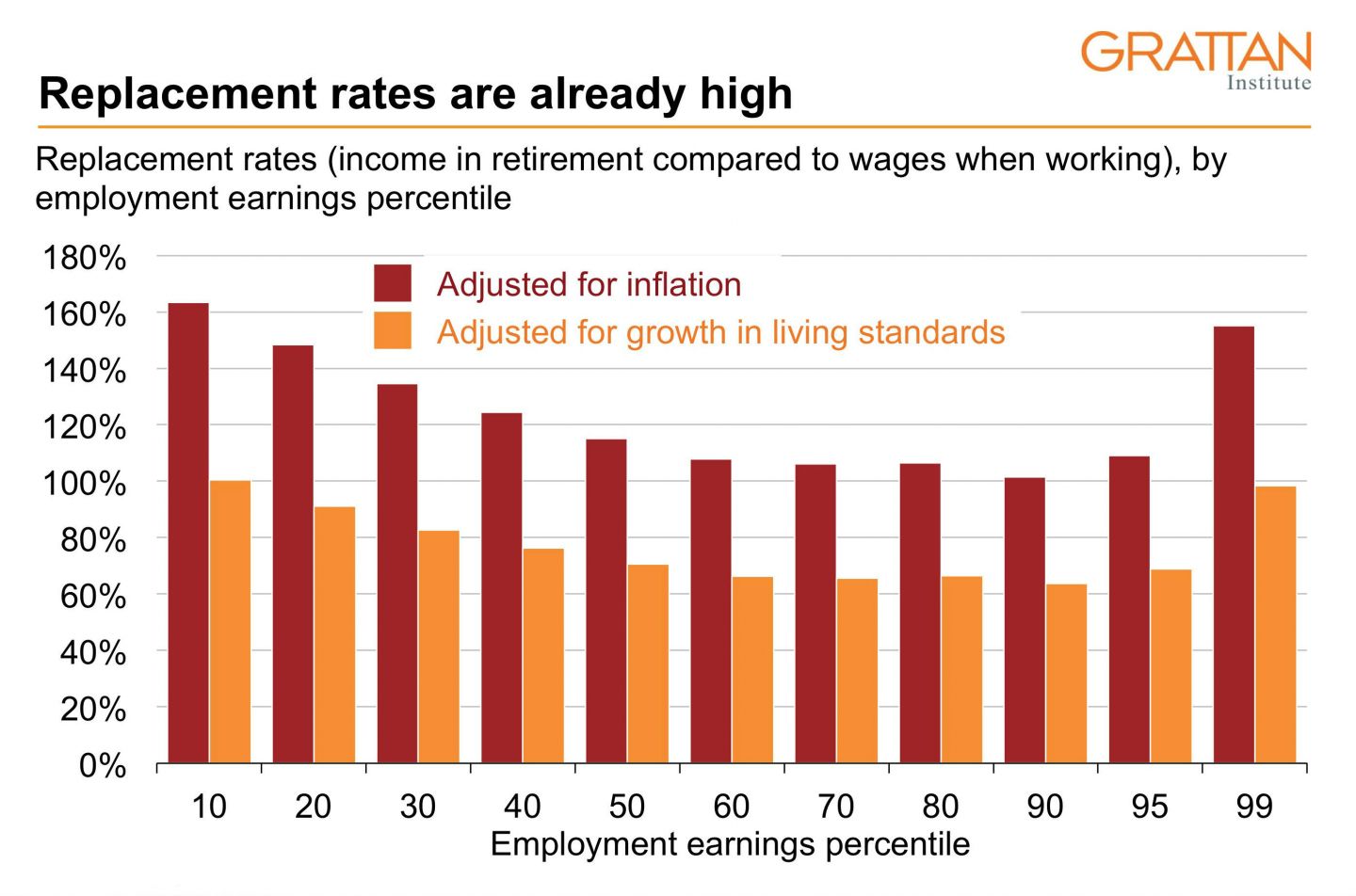

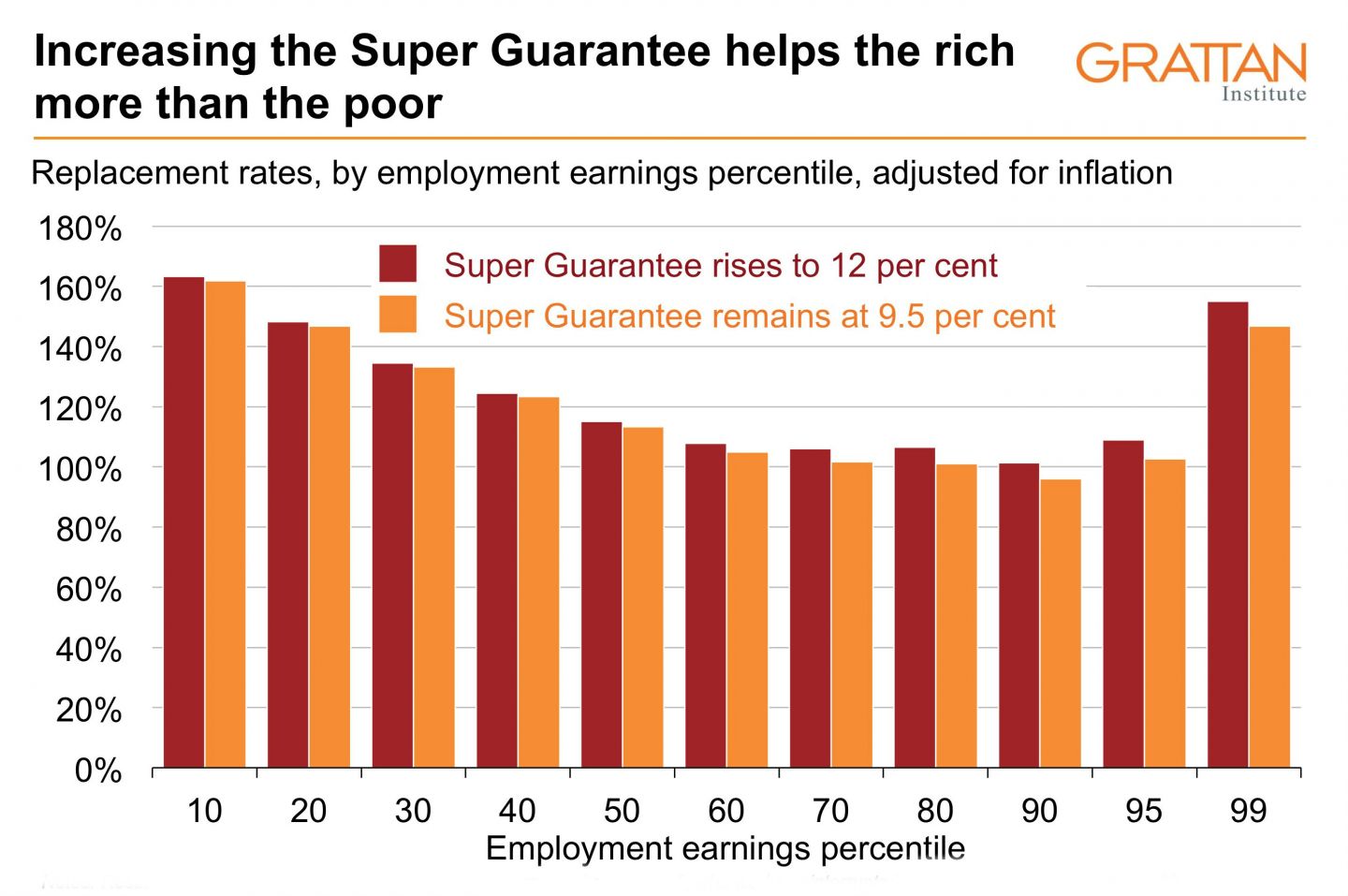

Our research predicts that low-income Australians who make compulsory super contributions for forty years will, after accounting for inflation, retire on an income of well over 100 per cent of their working-life wage. (This is also known as a “replacement rate” of more than 100 per cent.) In other words, many low-income Australians will get a rise in pay when they retire, because the age pension and the income they get from compulsory retirement savings will be higher than the wage they received during their working life.

Notes: Results from modelling the retirement income of a person born in 1985, who works uninterrupted from thirty to seventy, and dies at age ninety-two. Superannuation and pension policy is as legislated (Super Guarantee to rise to 12 per cent by 2025–26). Includes savings outside super. Employment earnings adjusted to account for movements up and down the earnings distribution. Retirement savings drawn down so that a small bequest is left in addition to the home. Source: Grattan Retirement Incomes Model

In calculating replacement rates, the super industry assumes that incomes should grow through retirement in line with future living standards, and not just keep pace with inflation. But it’s expensive — people must save through their working life for a higher standard of living after retirement than they had when they were working.

Even under this higher standard, though, Australians’ retirement incomes are still adequate according to international benchmarks. Most retirees can expect a wage-adjusted retirement income of at least 70 per cent of their pre-retirement income. Seventy per cent happens to be the replacement rate for median earners used by the Mercer Global Pension Index and endorsed by the OECD. Australian retirement incomes are even further above the World Bank’s target replacement rate for the average worker, which is 50 to 60 per cent of pre-retirement earnings. Most people have much lower spending needs in retirement, particularly in the later stages of life when government covers most of the significant costs of health and aged care.

Retirees of today — many of whom didn’t benefit from compulsory super contributions for their whole working lives — already feel more comfortable financially than younger Australians. The non-housing expenditure of retirement-age households is typically more than 70 per cent of that of working-age households. And pensioners who own their home are less likely to suffer financial stress — based on measures such as skipping meals or not being able to heat their home — than working-age Australians. The retirees of tomorrow might be more worried, but they can expect to be even better off than the retirees of today.

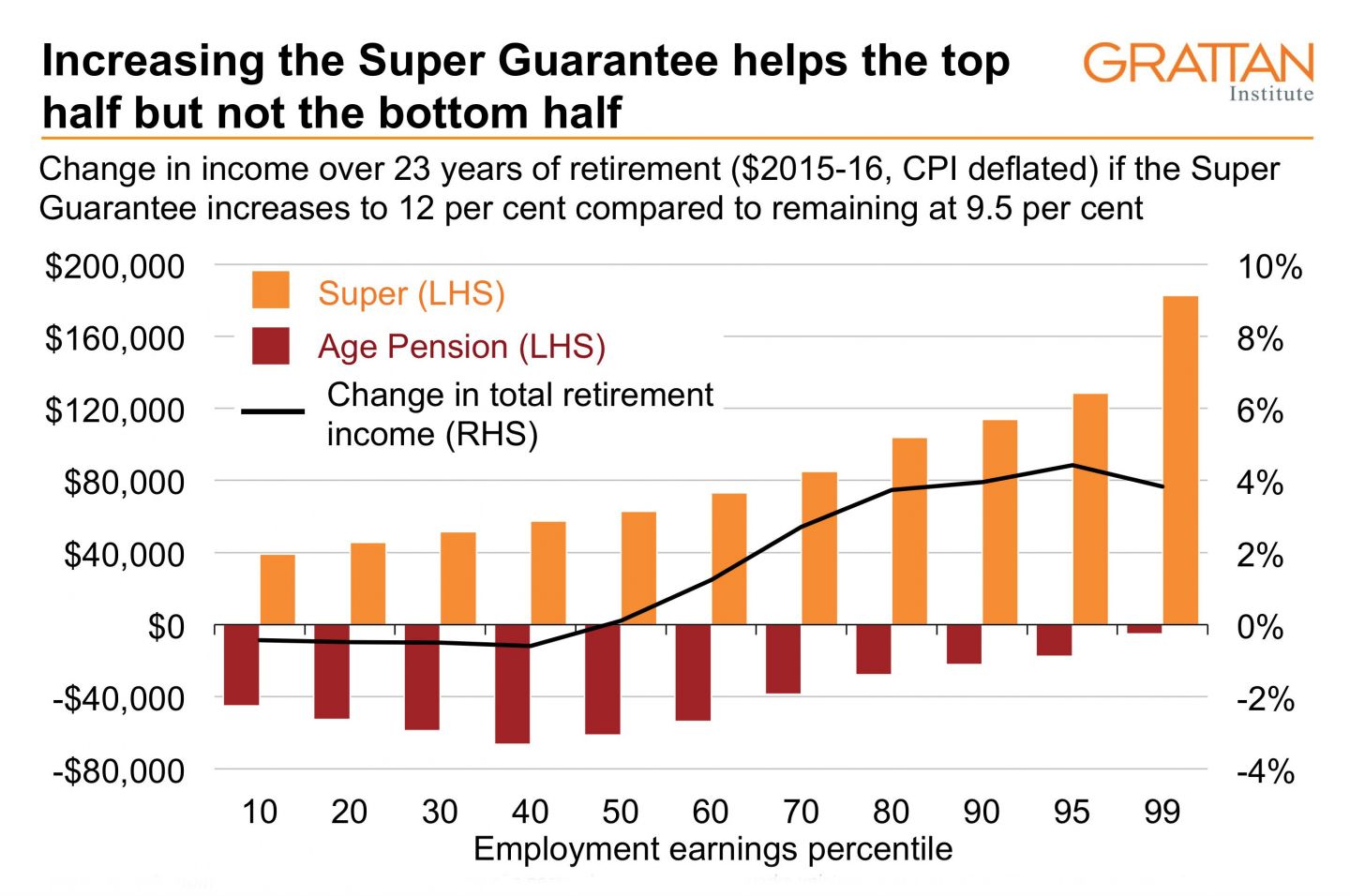

Notes: Results from modelling the retirement income of a person born in 1985, who works uninterrupted from thirty to seventy, and dies at age ninety-two. Includes savings outside super. Employment earnings adjusted to account for movements up and down the earnings distribution. Retirement savings drawn down so that a small bequest is left in addition to the home. Voluntary superannuation contributions partially offset the fall in compulsory contributions if the Super Guarantee remains at 9.5 per cent. Draw-down behaviour does not change. Assumes employees absorb any Super Guarantee increase in the form of lower wages. Source: Grattan Retirement Incomes Model

Of course, the super lobby wants you to believe another story. The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia, or ASFA, has prepared its own measure of what is needed to live a “comfortable” retirement, and argues that most workers won’t achieve it. Many have argued that, as a result, the average Australian isn’t saving enough.

But ASFA’s measure of a “comfortable” retirement supports an affluent lifestyle more luxurious than most Australians enjoy during their working lives. It was originally designed to quantify a “comfortably affluent” lifestyle for those in the top 20 per cent of retirees. Then it was relabelled as “comfortable,” which misleadingly implies that anyone with less income will be “uncomfortable.” The average household can only reach ASFA’s “comfortable” benchmark in retirement by being “uncomfortable” while working.

All of this means that increasing the Super Guarantee to 12 per cent will further increase replacement rates for low- and middle-income earners — but only at the cost of lower earnings during their working lives. In fact, increasing the rate may even reduce retirement incomes for low-income earners, for two reasons.

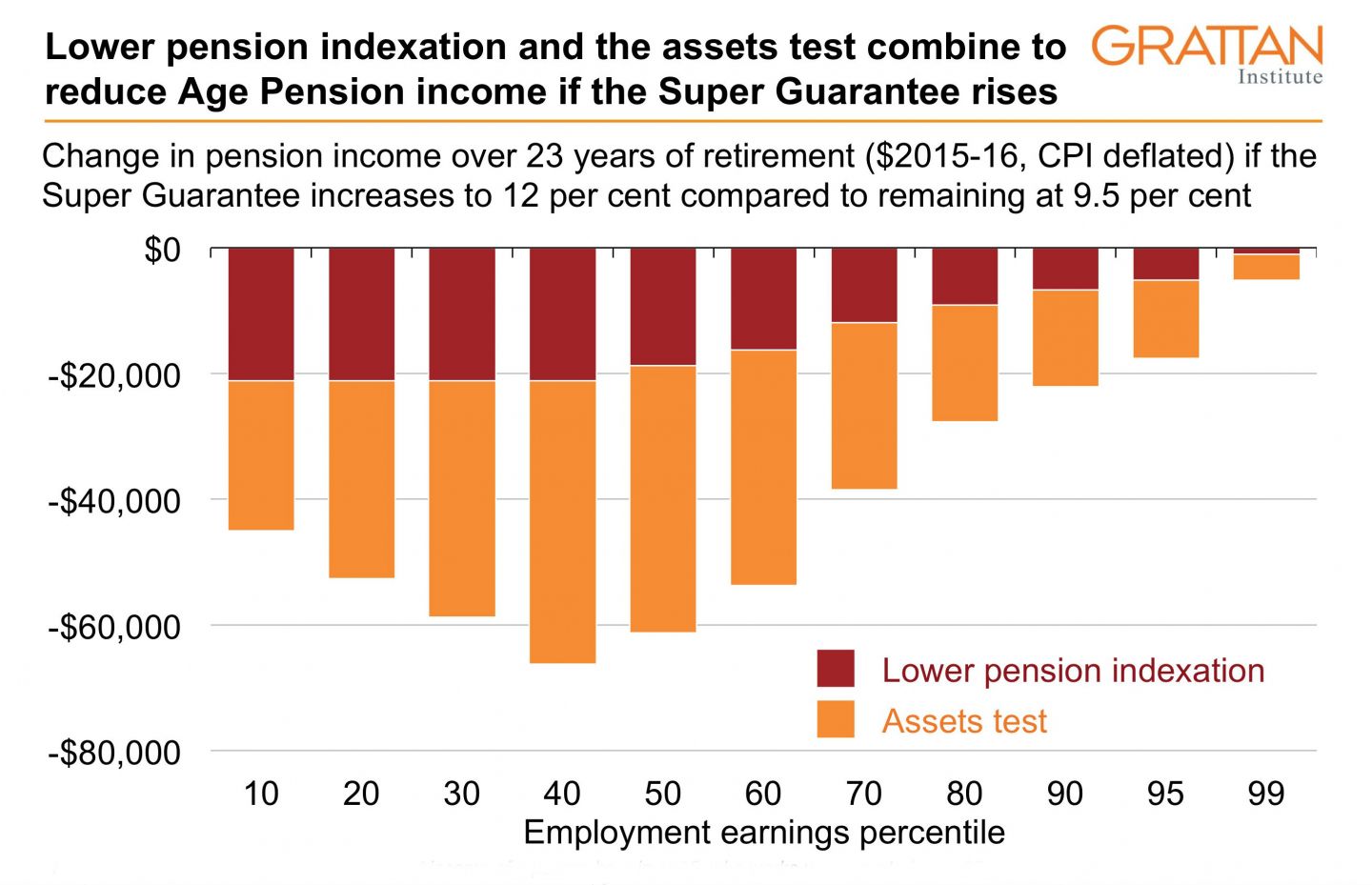

Notes: Results from modelling the retirement income of a person born in 1985, who works uninterrupted from thirty to seventy, and dies at age ninety-two. Superannuation and pension policy is as legislated (Super Guarantee to rise to 12 per cent by 2025–26). Includes savings outside super. Employment earnings adjusted to account for movements up and down the earnings distribution. Retirement savings drawn down so that a small bequest is left in addition to the home. Voluntary superannuation contributions partially offset the fall in compulsory contributions if the Super Guarantee remains at 9.5 per cent. Draw-down behaviour does not change. Assumes employees absorb any Super Guarantee increase in the form of lower wages. Source: Grattan Retirement Incomes Model

First, the more superannuation someone has, the less age pension they will receive in retirement. For each $1000 of assets above the pension asset test threshold — currently $253,750 for a single homeowner and $456,750 for a single renter — a pensioner now loses $78 a year in pension payments.

Second, the age pension is indexed to wages (which exclude compulsory super contributions), which means that increasing the Super Guarantee reduces pension growth. Our research shows that increasing the rate to 12 per cent would make future pension payments 2 per cent lower than otherwise. By suppressing the value of their pension payments, it could make existing pensioners worse off by up to $460 a year for singles and $640 a year for couples.

Notes: Results from modelling the retirement income of a person born in 1985, who works uninterrupted from thirty to seventy, and dies at age ninety-two. Includes savings outside super. Employment earnings adjusted to account for movements up and down the earnings distribution. Retirement savings drawn down so that small bequest is left in addition to home. Voluntary superannuation contributions partially offset the fall in compulsory contributions if the Super Guarantee remains at 9. 5 per cent. Draw down behaviour does not change. Assumes employees absorb any Super Guarantee increase in the form of lower wages. Source: Grattan Retirement Incomes Model

Nor will lifting the Super Guarantee do much to help women with broken work histories. Superannuation is a contributory system: since women tend to earn less than men over their working lives, they accumulate fewer retirement savings and receive lower incomes in retirement.

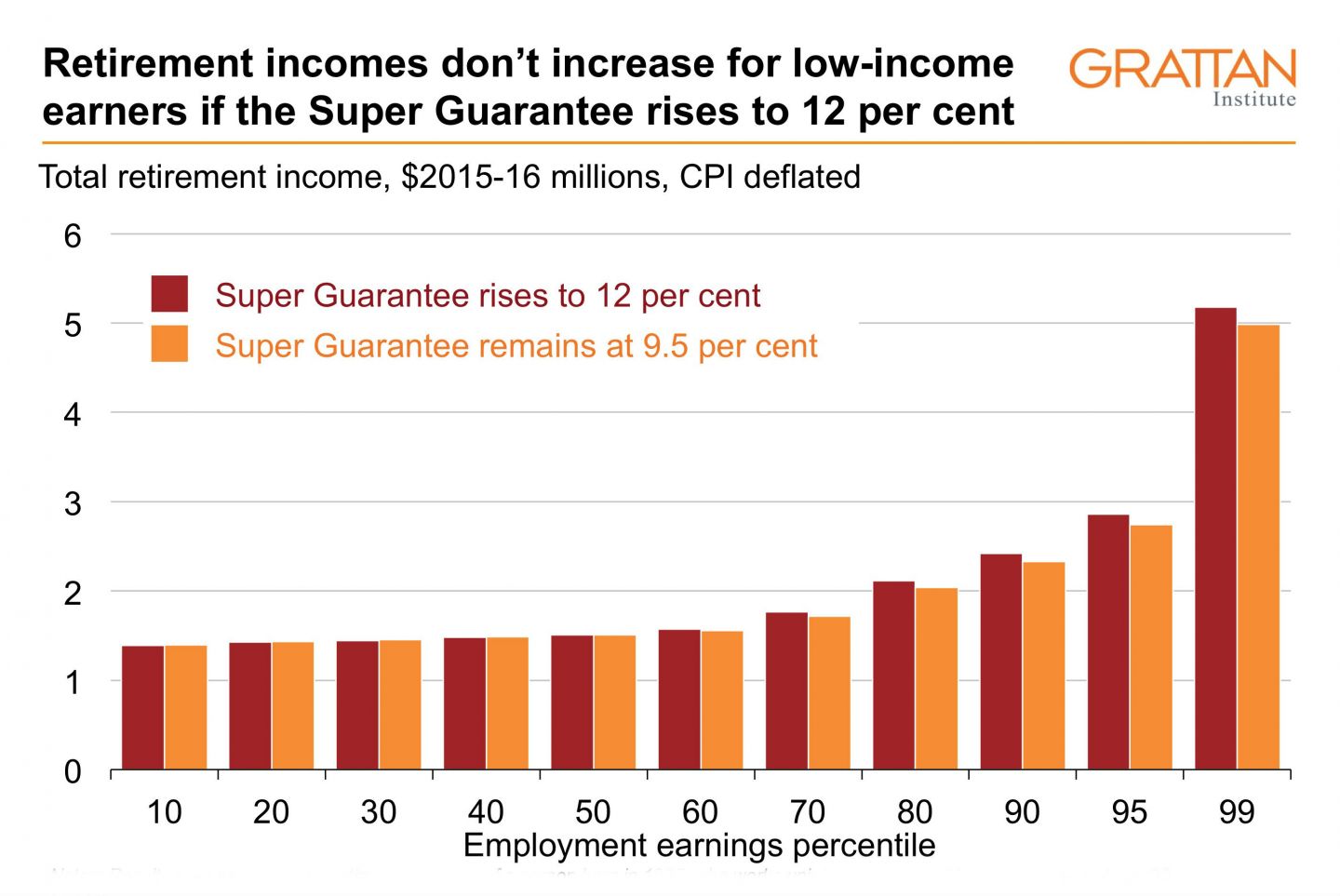

The main beneficiaries from a higher Super Guarantee will be high-income earners, who already reap most of the benefits from generous superannuation tax breaks. By being forced to put even more into super, they’ll no longer pay income tax on that income; it will instead be taxed at a flat 15 per cent rate as extra contributions to their super fund.

Notes: Results from modelling the retirement income of a person born in 1985, who works uninterrupted from thirty to seventy, and dies at age ninety-two. Includes savings outside super. Employment earnings adjusted to account for movements up and down the earnings distribution. Retirement savings drawn down so that a small bequest is left in addition to the home. Voluntary superannuation contributions partially offset the fall in compulsory contributions if the Super Guarantee remains at 9.5 per cent. Draw-down behaviour does not change. Assumes employees absorb any Super Guarantee increase in the form of lower wages. Source: Grattan Retirement Incomes Model

Raising the Super Guarantee doesn’t just reduce workers’ take-home pay, it also hits the federal budget. Instead of workers receiving wages that are then taxed at full marginal tax rates, the extra compulsory contributions to their super fund will be taxed at a flat 15 per cent. The 2014–15 budget calculated that delaying an increase to the Super Guarantee of 0.5 percentage points saved $440 million in 2017–18. Raising the Super Guarantee to 12 per cent could therefore cost the budget around $2 billion a year in additional tax breaks.

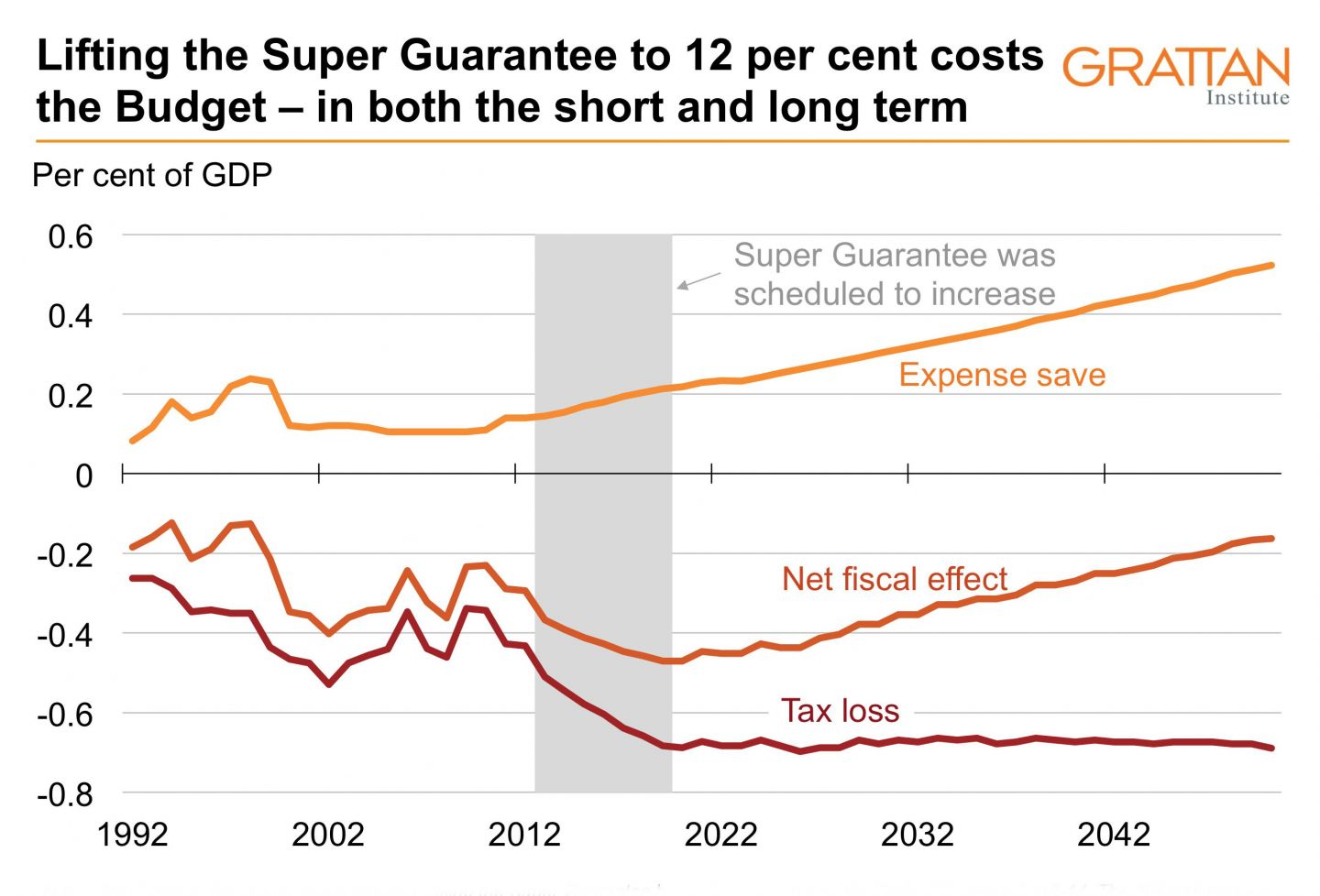

The purpose of superannuation is to save for the future and reduce future age-pension payments. In both the short and long term, though, superannuation costs the budget more than it saves, because the tax breaks cost the government more than the pension savings.

A Treasury analysis in 2013 estimated that the tax revenue foregone as a result of moving to a 12 per cent Super Guarantee, added to past increases in the Super Guarantee, would exceed the budgetary savings from lower age-pension spending by 0.4 per cent of gross domestic product a year. Eventually — by 2050 — the net budgetary cost of superannuation tax breaks will be “only” 0.2 per cent of GDP a year. On these trends, superannuation won’t start saving the budget money until about 2060 — and then there will be eighty years of budget costs to pay back before government is in front.

Based on these figures, the Super Guarantee, including the planned increase to 12 per cent, will increase Commonwealth net debt by 10 per cent of GDP by 2050. These numbers may have improved since the federal government changed the age-pension assets test and modestly tightened superannuation tax breaks. But even then, it’s unlikely that the Guarantee will “help” the budget any time soon.

Notes: The 2010–11 federal budget predicted that increasing the Super Guarantee by 0.25 percentage points would cost the budget $240 million in 2013–14. The 2014–15 budget predicted that not increasing the Super Guarantee by the previous government’s policy of 0.5 percentage points would save $440 million in 2017–18. These cost estimates were done before recent policy changes: a higher pension assets test taper rate and tightening of superannuation tax breaks. These changes will add up to a fiscal saving of 0.1 per cent of GDP in 2018–19 (higher taper rate saves $1 billion, super tax changes save $0.1 billion). Shaded area indicates 2010–11 budget policy. Sources: The Treasury Charter Group 2013; Budget papers; Grattan analysis

Despite what the super lobby claims, the current 9.5 per cent Super Guarantee — taken together with the age pension and non-super savings — is sufficient to deliver an adequate retirement income for low- and middle-income Australians. Increasing the rate will not help these earners in retirement: most of the benefits will flow to high-income earners, while low-income Australians could cop both lower incomes in retirement and lower wages today. And it will cost the budget money.

If our politicians really want to help low-income workers and are serious about fixing the federal budget, they should abandon plans to raise the Super Guarantee. They will need to act soon if they want to cancel the incremental increase in the Super Guarantee scheduled for July 2021, because new enterprise agreements currently in negotiation will take into account the increase in the Guarantee when setting wage rates. ●