First published 4 Sept; updated 9 Sept

WHILE the final composition of the Senate won’t be known for at least a fortnight, it seems likely that some micro-party candidates who attracted very little primary support will be sitting as senators after 1 July next year. In Western Australia, for example, the Australian Sports Party could gain a place with just 0.22 per cent of first preferences – as could the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party in Victoria, with 0.52 per cent. The Senate is too important to become a playground for recreational groups masquerading as political parties. System reform, including change to electoral procedures, is urgently needed.

Part of the problem is that the Senate voting system is complex and opaque. Senators are elected by way of a multi-member, quota-preferential, single-transferable-vote, proportional system. This mouthful, which is almost as complex as it sounds, is generally abbreviated to STV, despite the vision those three letters conjure up of a nasty social disease.

Under STV, each state is allocated twelve senators, six of whom usually face election at three-yearly intervals. The territories each have two senators, both of whom face the people at each ordinary election. In the House, a successful candidate needs an absolute majority of 50 per cent + one vote; in the Senate, each candidates must achieve a “quota” of votes – 14.4 per cent at the usual half-Senate elections, like the one on Saturday, or 7.7 per cent at the full-Senate elections that follow a double dissolution of both chambers (which last occurred in 1987).

The system allows the preferences of parties and independents eliminated from the count to be distributed in the same manner as in the counting of votes for the House. The major difference, and a key feature of STV, is that the “preferences” of the big parties are also distributed, even after they have won some Senate positions.

This works in two ways. The lead Senate candidates for Labor and the Coalition attract votes far in excess of what they need to win a place. Those surplus votes are transferred down the ticket and help elect other candidates from the same party. Since major parties rarely win exact quotas, their “surpluses” can also transfer on and help elect other parties’ candidates.

Take the example of New South Wales in 2010. After all the first votes were tallied, the Coalition had 2.3 quotas, which it built to three by harvesting preferences from a clutch of small right-wing parties such as the DLP and the Shooters and Fishers. Labor started with 2.2 quotas and was not so fortunate in reaping small-party support; rather than contributing to a third senator, its 0.2 surplus helped to elect a Greens candidate.

Most small and micro parties get elected by receiving the sugar hit of a partial quota from a big party. (The current exception is Nick Xenophon in South Australia, who again won his own quota.) It is this churning of preferences that can permit candidates who poll just a few votes to remain in the count for long enough to get elected.

A claimed virtue of proportional representation voting systems is that they allocate seats in direct proportion to votes won, so if a party wins 15 per cent of the vote it should receive 15 per cent of seats. The Senate isn’t quite like that because the existence of eight electorates (the states and territories) dilutes national proportionality. The system is best termed quasi-proportional.

Why did the parliament adopt this Senate voting system in 1948? Mainly because, under the old system, a party that achieved even the narrowest majority in a state won all three Senate places. Nevertheless, the opposition leader at the time, Robert Menzies, called the change to the present system a “racket” designed to maintain a Labor majority until 1953. In fact, the Labor majority was swept away at the 1951 double dissolution election.

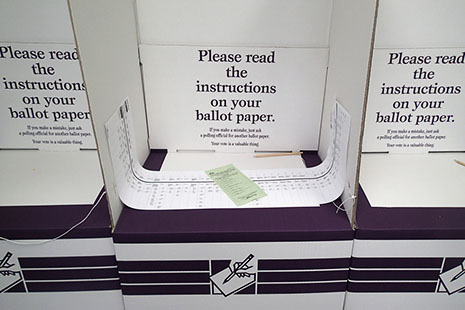

A controversial feature of the current system is the above- and below-the-line voting option. Above the line, voters cast a valid vote simply by entering the number 1 for the party of their choice; below the line, they must indicate a full set of preferences, which can mean numbering dozens of boxes. Above-the-line is a gift to party managers making preference deals of sometimes bizarre ideological inconsistency. It also means that the donkey vote can be crucial, as the Liberal Democratic Party discovered when it polled 9 per cent in NSW largely because it drew first position on the ballot paper. The below-the-line option raises the risk of pushing up the number of accidentally informal votes.

The above-the-line method was introduced by the Hawke government in 1983 to reduce the traditionally high Senate informal vote. But Labor was also keen to prevent a repeat of the 1974 election, when anti-Labor interests packed the NSW Senate ballot paper with dummy candidates and caused a spike in informal votes. The ruse cost Labor a quota, with devastating consequences for the party in 1975.

ON SATURDAY, voters were confronted with a record fifty-four political parties, 529 Senate candidates and 1188 House hopefuls across the states and territories. An unprecedented number of recently created micro-parties also participated. Some may view this as a sign of a healthy democracy, but they would be wrong. At least in New South Wales, the huge number of tiny right-wing parties running for the Senate was the result of the efforts of a political deal-maker, Glenn Druery, who specialises in constructing mutual preference arrangements in order to increase the chance of a victory by someone who enjoys minimal direct support.

The increased number of parties and candidates contesting House seats inflated the informal vote to a record 5.9 per cent. But it got into double figures in some Divisions, especially where there are large concentrations of people whose first language is not English. Traditionally these are Labor seats.

Reform is needed. First, the test for party registration should be much stricter. At the moment, all a “party” needs is $500, a brief constitution, and a list of 500 supporters entitled to be on the electoral roll. This should be increased to 2000 voters and a $20,000 nomination fee (or $10 per member – just over half the cost of a packet of cigarettes).

Second, the Senate ballot paper should be redesigned to abolish above- and below-the-line voting. Instead, voting should be optional preferential. At a normal Senate election, a voter would need to number at least six squares, and at a double dissolution election at least twelve. This would keep informal voting low and put a stop to secret wheeling and dealing over preferences and unexpected successes for candidates with extremely modest direct support.

Third, unless the lead candidate of a senate group or an ungrouped independent secures in excess of 4 per cent of the first vote, they should be eliminated from the count and their preferences distributed. This might seem harsh, but 4 per cent is the threshold candidates need to receive public funding and have their nomination deposit refunded, and seems a reasonable test of whether they have any real support in the electorate. •