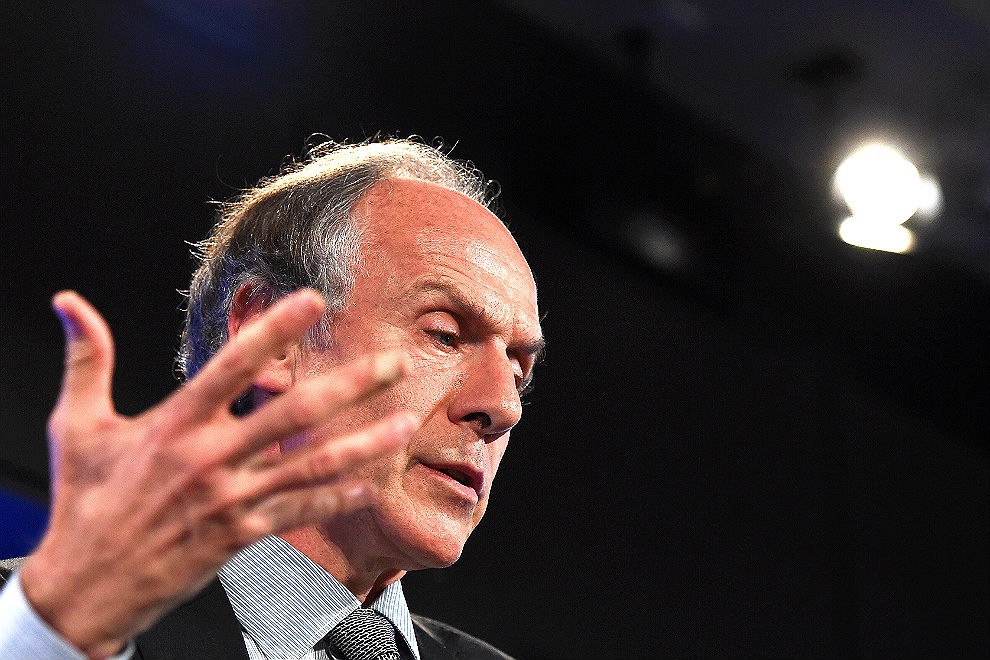

Chief scientist Alan Finkel got a lot of people very excited when he released his draft report into Australia energy security last December, less than three months after the September blackout put conservatives into a flap over wind and solar.

We were in the midst of an unstoppable energy transition, he said, one based on cheap renewables, storage and smart software. And the technologies to address the reliability and security issues were at hand, though they were not being encouraged by the design of the market.

The energy system, Finkel went on, would need to shift dramatically from a centralised model (aka coal plants) to a decentralised model (aka rooftop solar and storage). The power, quite literally would return to the people. It was all rather exciting.

Fast forward to 9 June, and Finkel’s delivery of his final report to Council of Australian Governments leaders in Hobart, and many people are wondering what happened in between. Blame the full moon or Dark MOFO happening in the same city, but Finkel’s view of the energy future didn’t look much different to the one we’ve got now.

What’s going on? Put simply, the chief scientist chose to deliver a political document rather than a scientific one. Sure, there is a lot of sound analysis, and Finkel has properly identified the regulatory holes, lack of planning, distorted market rules, the need for storage and the lazy and lax policy making that has made the Australian energy market the basket case it is.

But the big picture was missing. For reasons that can probably be guessed, Finkel chose to frame his energy future, and the security and reliability and cost issues, in the image of the current government’s less than ambitious climate policies.

He does, at least, show a path to get to a 28 per cent cut by 2030 using a clean emissions target, or CET, which he says is preferable to an emissions intensity scheme (though only because an EIS looks to the Coalition too much like a carbon price). Apparently he modelled no other scenarios, such as a higher renewable energy target.

Don’t tell the Coalition backbench, but the CET is effectively a carbon price too, though it includes carrots without any sticks. Low emissions technologies get credits, depending on how far below they are from a nominated benchmark, but there is no penalty to high emitters. Effectively, we are told, it should work like a renewable energy target with no technology barred, although its bite will depend on how ambitious the climate policies are.

The anticipated outcome caused dismay among environmental groups. Based on the Coalition’s current policies, it showed that large scale renewables would grow only moderately from 2020 to 2030, and account for just one third of all generation, or 42 per cent if you add in rooftop solar.

In 2050, the modelling suggested, brown coal-fired generators would still be operating, even some brown coal plants in the Latrobe Valley – in fact, more than in the business as usual scenario. Finkel reasoned that having coal plants last longer was more effective – cheaper and with less emissions – than building new plant, such as gas-fired plants designed to fire up during peak periods.

Effectively, though, he was writing off the idea of gas-fired generation as a transition fuel, agreeing with the likes of AGL and the renewables industry that solar and wind combined with storage beats baseload gas by a handy margin and peaking gas by a country mile.

But what about the science? Since when did the chief scientist become the policy fixer in chief for a Coalition split by a leader who everyone hopes would like to act on climate change, and a conservative rump that refuses to do anything at all.

Most (including me) saw the report as a disaster. “Finkel fail,” sniffed Solar Citizens. “Big coal and gas are licking their lips,” said Greens’ climate spokesman Adam Bandt. But Bloomberg New Energy Finance chief analyst Kobad Bhavnagri has another take.

Bhavnagri describes the plan as a “canny job of plugging holes in the country’s manifestly inadequate climate and energy policy framework.” The CET, he says, could solidify long-term investment in renewable energy, and help renew Australia’s decaying fleet.

But the weakness is the failure to assess its own plan against the 2ºC climate scenario, because that is the one that most businesses will want to work on. You can draw a line from One National senator Malcolm Roberts to former prime minister Tony Abbott, but no one this side of reality believes that the current government policy is in any way adequate.

“A 2 degree, net zero by 2050, emissions reduction pathway… is the core sensitivity that smart businesses around the world are assessing their resilience against,” Bhavnagri says. “Developing a ‘blueprint for the future’ means the plan has to be resilient against how the world could change. There is little in the Finkel review to indicate that his plan is future proof – it tackles today’s challenges, not tomorrow’s.”

But it may be that Finkel – normally the smartest person in the room – has deliberately withheld the modelling. We don’t know that he has done a 2C stress test, but based on his assumption about the cost of wind and solar, and the fact that storage is “arriving like a freight train,” it is difficult to imagine that this could allow any room for coal, or any other fossil fuels, by 2050. The Coalition doesn’t want to be told this, so Finkel hasn’t told them.

There are other concerns. Finkel’s solution to the problem of storage is to ascribe responsibility to individual wind and solar plants, rather than think of system-wide solutions. The renewables industry accepts the need for storage, but says there must be smart ways than this, and wonders why no such rules are applied to coal- and gas-fired generators that have shown a worrying tendency to fail just when they are needed most – in the middle of a heatwave.

But his other conclusions are broadly right. More planning is needed, the regulator needs to be kicked up the backside and instructed to keep up with technology, and more emphasis is needed on “demand side” initiatives that mean we don’t need to build new peaking-gas plants, the fuel guzzlers that are about as generous to consumers as credit card interest rates.

The final vote, however, will go to the consumer. Finkel promises that a CET will keep prices below business as usual, but not by much. Which surely makes one wonder. If SA Power Networks, the grid owner in South Australia, is predicting that solar and storage will cost just 15c/kWh by 2020, less than half of the cost of grid power, then how many consumers are going to remain connected in thirty years’ time, when solar and storage have fallen even further and the grid is still ridiculously costly?

Ultimately, it will be this that brings sense to the policy-makers. The possibility of climate catastrophe doesn’t seem to do it. •