For that old-style Jaffa-rolling movie experience, you can’t go past the State Theatre in Sydney’s Market Street. Built in 1929, it seats over 2000 patrons in the faux classical opulence favoured by early designers of picture palaces.

Today, this glorious temple to cinema hosts music, ballet, stand-up comedians and the annual Sydney Film Festival. But on a wet winter’s night back in 1966, a film that would help reactivate Australia’s moribund motion picture industry had its premiere there. Amid flashing bulbs, a procession of local celebrities and dignitaries tramped up a sodden red carpet. Foreign glamour arrived in the shape of the movie’s star, the Italian actor and comedian Walter Chiari. In spite of the weather, They’re a Weird Mob was being launched onto the world stage in some style.

Based on the bestselling novel by a former pharmacist called John O’Grady (writing under the pseudonym Nino Culotta), They’re a Weird Mob tells the – ever so slightly satirical – story of an Italian journalist’s encounter with the strange manners, language and rituals of postwar Australia. It’s a benign portrait of the migrant experience in Australia, and gently mocks the nation’s dominant Anglo-Saxon suburbanite culture. Published in 1957, it sold in its millions.

Besides its humour, the book probably found favour with Australian readers because it portrayed them in such a flattering light. Nino never encounters prejudice; he is accepted easily into Australian society because he accepts so easily its habits of speech and thought. Reading the book today, you have to remind yourself that it, and the film, were released at a time when Italian migrants would have been referred to in polite circles as “New Australians” but in the nation’s public bars as “wogs,” “dagoes” and “eyeties.”

Standing nervously backstage that night, “freshly made up with big hair and lots of eye make-up” and wearing a pair of fashionable culottes bought specially for the occasion, was a teenaged Jeanie Drynan. Fresh out of NIDA, she played Betty, the newlywed wife of Nino’s friend, Jimmy. Today, after a long and illustrious acting career, she is best remembered for her roles in classic Australian films like Don’s Party and Muriel’s Wedding.

“It was a big deal, a very big deal. There was lots of excitement about this film,” she told me recently by phone from her home in Los Angeles. After the film was shown that night fifty years ago, Drynan joined her older, more experienced cast mates up on stage: Chiari, Chips Rafferty, Ed Devereaux and Slim de Grey. A little bit of Hollywood hoopla had come to Market Street.

Also in the audience that night was a budding film-maker in his twenties called Anthony Buckley. He was working for the newsreel company Cinesound, helping to capture for posterity the damp celebrities on the red carpet. Buckley doesn’t rate the film highly, but he remembers it fondly. “We were starved for seeing something of ourselves,” he tells me, “even if it was a bit ocker.” Now retired from film-making, he went on to become the award-winning producer of films like Caddie and Bliss.

Though it wasn’t the best film ever to grace the screen at the State, They’re a Weird Mob contributed significantly to the idea that an Australian film industry revival was neither a fanciful idea nor a national folly. What we would call today a “co-pro” – partly funded with money from overseas – it was one of the very few Australian feature films that actually got made in the 1960s. It showed that Australia had actors and technicians talented enough to make films. Just as importantly, its financial success revealed that Australian audiences would pay to watch local films – if given the chance.

They’re a Weird Mob played to sellout audiences at the State for six months, and made over $2 million at the Australian box office nationally. (Perhaps not surprisingly, it bombed overseas. Maybe you had to live here to get the jokes.)

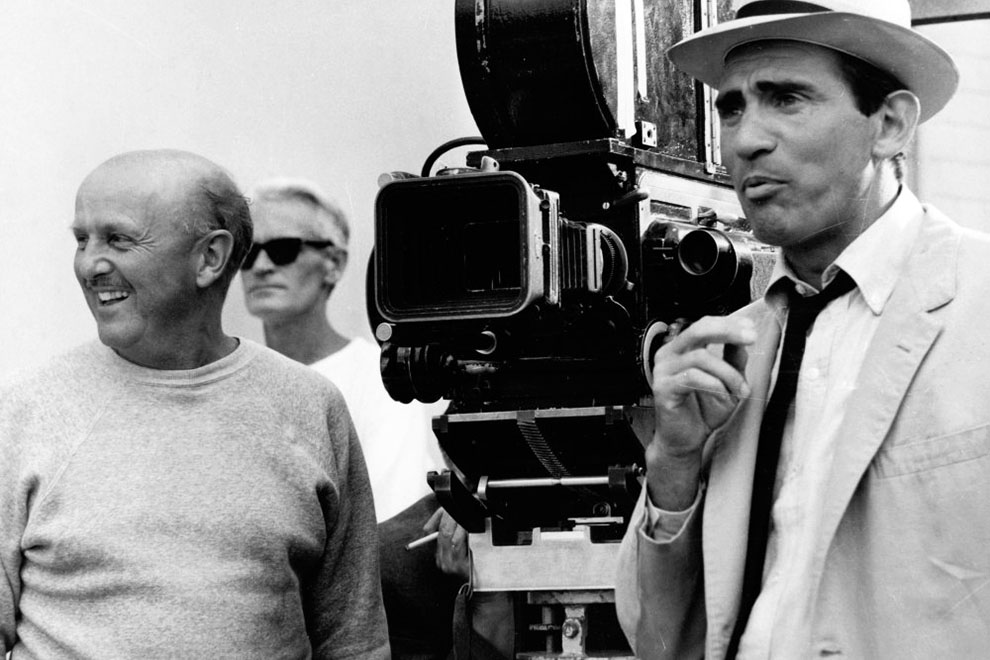

Skills and ideas: Michael Powell (left) and Walter Chiari on the set. British Film Institute

“They’re a Weird Mob woke the politicians up,” says Buckley, particularly the Liberals’ John Gorton and Labor’s Gough Whitlam. “Gorton led the push for film schools and film funds to be established, which was later followed up by Gough. And you can thank films like it for setting up Australia’s film renaissance in the 1970s.”

Like that other pioneering work that helped reawaken Australia’s slumbering film industry – Wake in Fright, directed by the Canadian Ted Kotcheff – They’re a Weird Mob was also the work of an outsider. In fact, the man who made it was a very English Englishman.

In 1960 the veteran British film-maker Michael Powell released a masterpiece that pretty much destroyed his career.

Peeping Tom is a Hitchcockian thriller featuring a serial killer who likes to film his victims in their death throes. It’s as much about the voyeurism of cinema as it is about the act of murder. Contemporary critics hated the film with a rare vehemence. It was widely dismissed as evil pornography. Maybe the critics objected to seeing their profession explained away as a brigade of psychopaths sitting in the dark. The film was even banned in Finland.

Today Peeping Tom is widely considered to be one of the most important films of the twentieth century, but at the time it seemed as if Powell had sabotaged his ability to get films financed – which had been considerable.

With his partner, the screenwriter Emeric Pressburger, Powell had established a production company they called The Archers, which became a byword in British film-making achievement. The Archers produced many of its best films for the Rank Organisation, including the Oscar-winning films The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus. Martin Scorsese has called this body of work “the longest period of subversive film-making in a major studio, ever.”

But that was in the past. By his own estimation, Powell spent the two years after Peeping Tom “floundering about.” The only project he had on the boil was a musical about an island paradise transformed into a nuclear power station, called E=mc2. It sounds like box office radiation poison – and probably would have been.

Around this time, a friend gave Powell a copy of They’re a Weird Mob. He read it on a flight from London to the south of France, where he owned a famously unprofitable hotel called La Voile d’Or. He later recounted that he laughed all the way to the French Riviera and fell in love with O’Grady’s steatopygous hero. (Nino Culotta, loosely translated, means “Johnny Big-Bum.”) He was particularly taken by the language of O’Grady’s “Sinnyites,” which he described affectionately as “a highly spiced mixture of cockney and Liverpool Irish.”

By the time his plane touched down in Nice, Powell had decided that a film of the book had to be made. But when he rang the author’s agent in London, Powell was bemused to discover that the film option had already been taken by an unlikely party: the Oscar-winning actor Gregory Peck.

“This was too easy,” Powell writes in his (digressive and somewhat unreliable) memoir, Million Dollar Movie. “Greg was staying in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat with his family, about a hundred and fifty yards up the road from the hotel. I caught him at home.”

When Peck had been in Australia filming On the Beach for Stanley Kramer, his co-star Fred Astaire had lent him a copy of O’Grady’s novel. Peck thought the book was a hoot. “It was so wonderful reading it in Australia, and having all the people around us just like they are in the book,” Powell reports Peck telling him. His plans had stalled, though, and so Powell eventually acquired the rights and took up the long battle to put They’re a Weird Mob on the screen.

As any honest auteur will tell you, the greatest of all film-making arts is the art of finding the cash. The energetic Michael Powell had the soul of an artist but the spirit of a carnival spruiker; and like the proverbial shark he was always on the move, sniffing out deals.

“What showman wants to be financially independent?” he once pronounced. “Half the fun is coaxing money out of other people’s pockets into your own.”

Within weeks of reading the book, he was winging his way to a country he had never visited and knew little about. But he had the whiff of a movie in his nostrils, and nothing else mattered. Years later, after the film was finished, a critic asked Powell what possessed him to make it. “Oh, because I had never been to Australia before, and I liked the book,” he replied airily.

In November 1962 Australia was still in the grip of the tyranny of distance. On his first marathon trip to Sydney, Powell flew from Rome via Teheran, New Delhi, Bangkok, Singapore and Perth. At the end of this slog through the skies, Powell arrived at Mascot Airport stupefied by jet lag, but optimistic and ready for action. Australians were flattered by the interest shown in their culture by this world-renowned director. For his part, Powell found his hosts to be pleasingly similar to O’Grady’s portrait of them.

During his stay, Powell took a crash course in the mores of Australia. One evening, O’Grady escorted Powell to Sydney’s famous Marble Bar.

The unlamented six o’clock swill was approaching its apogee when Powell was accosted by a local:

A very drunk man said to me, “Excuse me, sir, but you are impeccably dressed.”

I said, “Thank you.”

He said, “You are the most impeccably dressed man that I have ever seen.”

I began to feel self-conscious, and drank some beer.

He said, “That tweed, I’ll bet it’s made from the best tweed in Scotland.”

I said, “From Donegal.”

“That’s what I said.”

Following up on a tip from Peter Finch, Powell had already found his Nino – Chiari, a man of great charm who also spoke perfect English. Powell renewed an old acquaintance with the actor John McCallum, who fortuitously was now working for J.C. Williamson, Australia’s foremost showbiz empire. The two men were kindred spirits: McCallum wanted to kickstart a broken-down Australian film industry; Powell wanted to make a film – anywhere, even in Australia.

But now he needed a script. So he wrote one. It was no good. O’Grady wrote another. It would have run four hours, according to Powell.

Powell then approached his old partner in crime, Emeric Pressburger. According to Powell’s account, Pressburger quickly identified the problem.

“There is no story, Michael.”

“Isn’t there?”

“Oh, Michael, Michael… How many times have I told you that a film is not words. It is thoughts, and feelings, surprises, suspense, accident.”

“When could you start?”

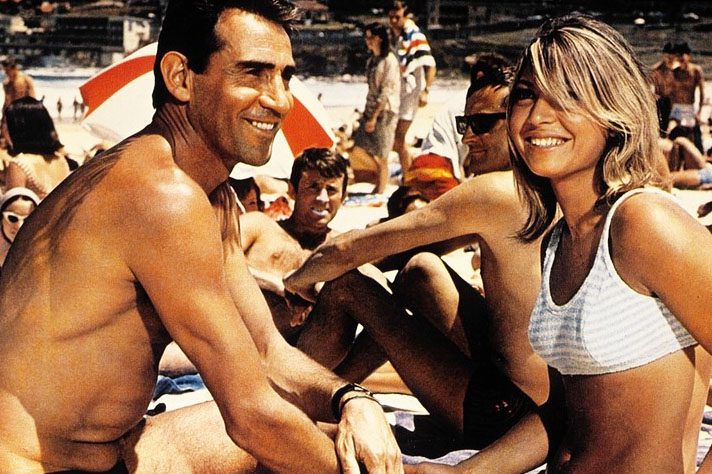

Ten days later, Powell got a new script – 114 handwritten quarto pages – and there was now a story. Right at the very start, in Pressburger’s version, Nino meets an Australian beauty called Kay (played by Claire Dunne), whom he courts throughout the film. In the novel, Kay doesn’t arrive until the last quarter of the book.

So an Australian comic classic was now being directed for the screen by a Pom from a script by a Hungarian-born Jew (mysteriously credited as “Richard Imrie”) who had never been in the Southern Hemisphere, let alone to Australia.

It took three more years – and three more marathon plane trips by Powell – but in November 1965 the indefatigable director was back at the Marble Bar, surrounded by real-life extras drinking real-life schooners, filming Chiari (as Nino) being introduced to the rituals of beer drinking in 1960s Australia.

The critics have never really warmed to They’re a Weird Mob. Writing in Nation, Sylvia Lawson offered a typical contemporary view, calling the film “tenth-rate,” “slap-dash” and “very scrappy-looking.”

But the acerbic Lawson also pointed out that Powell’s movie is “a frustrating glimpse of what it would be like to have our own film industry, of how it might be to have your city given back to you on the screen.”

In this glimpse a lot of dreams were born. A critical mass was developing in Australian film culture. Within a decade of the premiere of They’re a Weird Mob, the Australian film industry had produced Sunday Too Far Away, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and The Devil’s Playground.

It could also be argued that the commercially successful Barry McKenzie films made by Bruce Beresford in the early 1970s owe a debt to Powell’s early stab at the “ocker comedy.” Later comedies like Muriel’s Wedding and Strictly Ballroom are also in a direct lineage.

Powell’s sojourn in Australia is usually ignored when his life story is written up in the media. The traditional narrative assumes his film-making career disappeared into a deep hiatus in the wake of Peeping Tom until he popped up again as a mentor and friend to Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola in the 1970s.

In fact, Powell worked again in Australia. He directed the feature Age of Consent, based on a Norman Lindsay book, starring James Mason as an ageing artist and a very young – and occasionally naked – Helen Mirren as the muse who gets him back to the paintbrushes. A still young Anthony Buckley worked as the film’s editor on Dunk Island in Queensland, where it was shot.

The film marked the beginning of Buckley’s long friendship with Powell. Buckley visited him many times at his home in England, and received numerous postcards from Powell in the remaining years of the director’s life. Powell even visited the set of Caddie, which Buckley made with the director Donald Crombie in 1975.

Buckley remembers him as a highly skilled and disciplined director. “If he didn’t need it, he wouldn’t shoot it,” he told me. “There are not many directors who are that sure of themselves, but he was so economical. He was a true artisan.”

It’s an aspect of Powell’s legacy in Australia that is rarely commented on: his mentoring of young Australian film-makers. He brought skills and ideas to our local industry at a time when it needed them.

Like most film-makers, Powell abandoned more films than he managed to make. In the years after They’re a Weird Mob, he had wanted to make another film in Australia called The Coastwatchers, set during the second world war. He wanted to make a film called Taj Mahal with Rudolf Nureyev. He wanted to make a film in Russia about the ballerina Anna Pavlova. But he made none of them. Many more projects were cast aside for want of finance or studio interest.

Powell made his last movie in 1972. The Boy Who Turned Yellow, a short film for children, was his final collaboration with Emeric Pressburger, who wrote the script. Michael Powell died in 1990 at the age of eighty-five. That’s nearly twenty years without making a movie. It must have driven him crazy.

As Buckley says, “He was all the time going somewhere to do a deal to get a picture up and he died doing that. He didn’t stop dreaming.” •