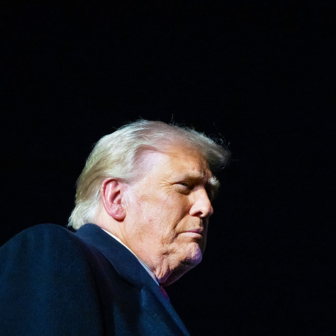

In American political jargon, an “October surprise” is a news event during the last days of a presidential campaign designed to influence the outcome of the election. The nastiness of the 2016 campaign means that October surprises were more or less guaranteed, and so we have seen the release of a 2005 video tape in which Donald Trump makes obscene remarks about women, a dozen first-hand accusations of groping or sexual assault, again by Trump, and then, late last week, the announcement of a renewed FBI inquiry into Hillary Clinton’s emails.

This latest hit to the Clinton campaign comes at a critical time. Polls showed Clinton surging ahead in national and swing states and Trump faltering, if not spiralling out of control. Small wonder that Clinton insiders have described FBI director James Comey’s letter to Congress about the renewed email investigation as “like an eighteen-wheeler smacking into us.” And no surprise that the floundering Trump campaign (“Think of the bunker right before Hitler killed himself,” said one anonymous campaign staffer last week) has seized on the news with a glee that has revitalised its rallies.

The media coverage has been out of all proportion to the cryptic official statements about what may or may not be involved in the renewed inquiry. For the Hillary haters, though, anything that links Clinton, emails and the FBI is enough, and the addition of Huma Abedin, Anthony Weiner and sexual peccadillos adds kerosene to the fire. But the actual impact on voters appears to be much less than the impact on avid supporters in both camps.

Such late surprises – some happen in September, or in early November – are not new to the 2016 campaign, so it’s possible to look back and see how, or even if, they affect the trajectory and the outcome of the presidential race. What history shows is that the largest last-minute impacts are more likely to come from consequential world and natural events than from political strategies to sabotage campaigns.

In September 2012, a secretly recorded video showed Republican nominee Mitt Romney claiming that 47 per cent of Americans pay no taxes and see themselves as victims entitled to government services. These comments fed into an existing narrative about Romney as an elitist candidate who didn’t understand the needs of ordinary people. But many pollsters see Obama’s last-minute boost in that election as coming from the way he handled Hurricane Sandy, which hit the eastern seaboard on 29 October and caused major damage, particularly in New York and New Jersey. The disaster gave him the chance to look presidential and dominate the media coverage; from 29 October to 5 November, positive stories about Obama (29 per cent of stories) outnumbered negative ones (19 per cent). It boosted an advantage Obama already had over Romney on the issue of “who do you trust to do a better job handling an unsuspected major crisis?”

Four years earlier, in 2008, the campaign kicker came on 15 September when the Lehman Brothers investment bank filed for bankruptcy, setting off a stockmarket crash and the global financial panic that voters largely blamed on the Republicans in power. Republican nominee John McCain didn’t help his cause by declaring that “the fundamentals of the economy are strong,” a statement that Obama used to good effect in his winning campaign.

In the 2004 election, Democrat John Kerry’s campaign fought hard to keep the contest from simply being about the 9/11 attacks, but all this was undone when, in the final weekend of the campaign, Al Jazeera released a video from Osama bin Laden lauding the attacks and criticising President George W. Bush. This brought the issue of the management of terrorism, on which Bush had a big lead over Kerry, to the front of voters’ minds, and Kerry’s poll figures fell dramatically.

A politically motivated November surprise was sprung in 2000, when, five days before the election, a supporter of Democratic candidate Al Gore revealed to the media that George W. Bush had been arrested on a drink-driving charge in 1976. Although Bush won (just), many of his advisers thought the news depressed turnout among social conservatives, and Bush strategist Karl Rove claimed the election result might have been different if the story hadn’t surfaced so late in the campaign.

And so it has gone in almost every presidential campaign, with foreign political powers sometimes also playing a role. When Iran announced just days before the 1980 election that it wouldn’t release the Americans being held hostage in Tehran until after the result, conspiracy theories quickly appeared. President Jimmy Carter had been trying, unsuccessfully, to secure the release of the hostages for over a year, and there were claims that Reagan’s campaign manager and others negotiated privately with the Iranians to ensure that the hostages wouldn’t be released before the election, to avoid a boost to Carter’s chances of Carter’s re-election. The fifty-two hostages were released as Reagan’s inauguration was under way, but two congressional investigations found no proof of a conspiracy.

Small wonder then that after WikiLeaks released a trove of emails from the Democratic National Committee in August, Democrats began to worry that more leaks were yet to come and to speculate about the role of Russian hackers. Are more emails still to come? Will someone release information about Trump’s tax returns? The possibility exists, but the fact is that any further revelations will come too late for the many Americans who have already voted.

In fact, early voting has become increasingly popular in the United States, perhaps driven by the fact that election day is a working day for many. In thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia, any qualified voter may cast a ballot in person during a specified period before election day; several states automatically mail or email ballots to all voters. In 2012, some 31 per cent of Americans cast their ballot ahead of time. This year, the earliest ballots were cast before any of the three presidential debates or the vice-presidential debate, and 40 per cent of voters are expected to have voted, some by mail, some in person, before 8 November.

But back to the impact of the FBI’s October surprise. Pollster Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball finds the “Comey effect” to be real and impossible to ignore, but detects no immediate signs that the overall race – which may have been tightening anyway as some Republican partisans reluctantly return to their party’s ticket – has changed dramatically as a result. At FiveThirtyEight, Nate Silver comes to a similar conclusion: the margin is closing, he says, because Trump is gaining ground from undecided voters and third-party candidates rather than because Clinton is losing support.

The RealClearPolitics average of the national polls has Clinton three points up, with only the outlier Los Angeles Times/USC Tracking poll giving the race to Trump. The New York Times’s analysis has Clinton at 45.8 per cent and Trump at 41.3 per cent, and gives Clinton an 89 per cent chance of winning. The Huffington Post’s tracking of 357 polls from forty-four pollsters finds that Clinton is ahead by six points (48.5 per cent to Trump’s 42.1 per cent). All of the forecasts of electoral college votes at 270toWin currently have Clinton already on 270-plus, despite the varying numbers of swing states.

It does seem that Comey’s October surprise has made key states like Arizona, Florida and Ohio more competitive. Larry Sabato has moved these from “Leans Democratic” to “Toss Up.” Ohio has long been considered a bellwether state – since John Kennedy in 1960, no candidate from either party has won the White House without winning Ohio. But with changing demographics shifting the focus to Hispanic voting patterns in Florida, Arizona and North Carolina, this year might be different. There’s been a dearth of polling in Ohio, but the RealClearPolitics average has Trump just ahead by 1.3 points.

Predicting the final outcomes of the Senate and House races is more difficult. The race for Congress appears to be very tight. In a new Politico/Morning Consult poll conducted after the release of the Comey letter, 44 per cent of people said they would vote for a Democratic candidate and 43 per cent said they would vote for a Republican candidate. The real urgency for Clinton is to get out the vote. She has the organisation, resources and high-profile surrogates to ensure this happens, and her campaign strategists know that every vote counts.

The pattern of early voting reflects both the Clinton campaign’s big advantage in get-out-the-vote infrastructure and the Democratic Party’s strategy of “banking” reliable votes early so that election-day resources can focus on persuadable or marginal voters. The Reuters/Ipsos States of the Nation project shows that Clinton leads Trump by fifteen percentage points among early voters and has an edge in swing states such as Ohio and Arizona, and in Republican Party strongholds such as Georgia and Texas. Voter registrations and requests for early ballots show Democrats surging in Florida, and there have been more Democrat requests and fewer Republican requests for absentee ballots in North Carolina than this time in 2012.

Trump, on the other hand, has little organisation, far fewer resources, and little interest in the details of the on-the-ground game. He has never really moved beyond the campaign rally. To the extent that he has a strategy, it is focused around driving efforts to discourage or prevent minority groups from voting, sometmes by intimidation. I have written previously about the difficulties that many voters, especially those from minority groups, face in casting their votes in Republican states. Trump has urged his supporters to monitor polling locations in cities like Philadelphia and St Louis, which have high minority populations, citing concerns about voter fraud and election rigging.

This week, Democratic Party officials have taken action to sue Trump in the four battleground states of Pennsylvania, Nevada, Arizona and Ohio in an effort to shut down what they call a “campaign of vigilante voter intimidation” that violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act and an 1871 law aimed at the Ku Klux Klan. Ironically, the first person charged in 2016 with the rare crime of voter fraud is a Trump supporter who voted twice in Iowa because she feared that the election was rigged.

As the 2016 presidential contest between the two least popular nominees in American history enters its final week, the focus remains where it has always been – on Trump’s sexual mores and Clinton’s trustworthiness. A recent analysis by the Tyndall Report shows how little time the flagship television news programs have devoted to policy topics as important as terrorism, climate change, health, gun control, immigration and foreign policy. No attention has been paid to the fact that Trump’s campaign has posted just seven policy proposals on his website, totalling just over 9000 words, while Clinton’s website features thirty-eight detailed proposals, ranging from efforts to cure Alzheimer’s disease to reforms of Wall Street and criminal justice. Combined, the three major network newscasts have spent one hundred minutes so far this year reporting on Clinton’s emails but just thirty-two minutes covering all policy issues.

Voters view Clinton’s emails and Trump’s sexually aggressive comments about women as equally bad, and 45 per cent of voters say they agree with Trump’s claim that Clinton’s email scandal is worse than Watergate. Their minds were made up months ago and recent events have reinforced opinions rather than changed them. So it’s no surprise that the majority of Americans viewed Clinton as untrustworthy and secretive long before last Friday’s letter from the FBI director but still deem her more fit to serve as president than Trump.

On just one issue, the majority of Americans can agree: nearly everyone wants this election to be over. With a week to go, four out of every five Americans say they wish the election was behind them, and just 12 per cent say they’re enjoying watching things play out. •