Older generations might panic about the perceived ignorance of history among the young, but the historical activities found in every corner of our culture provide a striking counterpoint. Family history never stops booming. Anzac history is driven both by feelings of national pride and by family pride among those whose relatives fought in Australia’s wars. The penal past, once a point of embarrassment, has become a source of satisfaction, especially if you can find a convict in your family tree.

But what happens when we ask Australians not about a distant past but about events in their own lifetimes? What do they see as the occurrences, at home and abroad, that have most shaped their country?

The Social Research Centre’s Historic Events Survey provides a snapshot of Australian historical consciousness. It asked its Life in Australia panel members — aged eighteen to ninety-three — what they saw as the “ten most important historic events” in their lifetime. It then asked them to choose a single event among their ten that had “the greatest impact on the country.” Subsequent questions invited respondents to reflect on which event made them proudest of, and which most disappointed in, Australia.

When the Pew Research Center in the United States asked Americans for their top ten in mid 2016, more than three-quarters included the September 11 terrorist attacks. Far fewer Australians, just 27 per cent, nominated 9/11, but this still placed the event second, just behind the same-sex marriage vote with 30 per cent. And when Australian respondents were asked to nominate the single most significant nation-shaping event of their lifetime, the most common choice was 9/11 (11 per cent).

Still, the lower rating of 9/11 in the Australian survey reminds us that national differences matter. Not only does 9/11 have much greater recognition as historically significant in the US, but so do the Vietnam, Gulf, Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Australia is wired in to US perspectives on world events, but we are not quite “Austerica,” as some intellectuals worried we were becoming in the 1960s. It is notable, however, that the two youngest Australian generations each included the election of Donald Trump at the tail of their top tens.

Evidently, then, responses to such matters reflect generational differences. Of the five generations considered, only gen X (aged thirty-eight to fifty-two in 2017) had 9/11 first, with 35 per cent of the vote. This group also ranked highly the Bali bombings of 2002 (eighth, with 11 per cent, a higher proportion than any other generation). Many of the eighty-eight Australians killed in Bali, being in their twenties and thirties at the time, belonged to gen X. And the response to 9/11 reflects the fact that Australians see that event as part of a wider pattern of terrorist threat rather than as a specific US experience.

Australian respondents younger than gen X had 9/11 second, behind same-sex marriage. For these millennials (aged twenty-three to thirty-seven) and members of gen Z (twenty-two or younger), other terror events, such as the Bali bombings and the Lindt Cafe siege, were also prominent in their ten. In sum, for anyone younger than about fifty, terrorism provides a powerful defining historical experience, despite the small scale and relative paucity of attacks on Australian soil.

Baby boomers (aged fifty-three to seventy-one), by way of contrast, rated 9/11 as low as fifth (20 per cent), while for the silent generation (aged seventy-two to ninety-three), with their longer perspective on twentieth-century international conflict, it was not in the top ten at all (it came in at eleventh). Those born in 1945 or before nominated the second world war first, with a hefty 44 per cent placing it in their top ten, the largest figure for any event in any generation.

The Historic Events Survey was carried out online and via telephone between 13 November and 3 December 2017, when same-sex marriage was prominent in public debate. The survey results contradict claims advanced, mainly by opponents of same-sex marriage, that ordinary Australians regard the issue as unimportant. Indeed, 45 per cent of respondents nominated issues that could broadly be categorised as “human rights” or “civil liberties,” belying the frequent claim that Australians are concerned overwhelmingly with material or economic issues. So much for “jobs and growth.”

When respondents were asked about the most significant single event in their lifetime, same-sex marriage came in second at 7 per cent, behind 9/11. When they were asked what made them most proud of Australia, 13 per cent mentioned same-sex marriage, while 6 per cent were most disappointed at the cost and delay involved in bringing the reform about, and another 6 per cent nominated its achievement as their most disappointing event. When the top ten is considered, same-sex marriage was first for both gen Z and millennials. But for gen X it appeared less frequently than 9/11, while the baby boomers only had it at three (24 per cent), and the silent generation at six (13 per cent). For the two youngest cohorts, alongside their consciousness of the changes wrought by terrorism is a sense of profound transformation around gender and sexuality.

By way of contrast, baby boomers don’t appear to have been much preoccupied with the “identity politics” of race, gender and sexuality. The events that are usually seen as critical in their formation and experience are there: the Vietnam war at one (28 per cent), the Whitlam government dismissal at two (27 per cent) and the Apollo 11 Moon landing at four (21 per cent). This is seemingly a generation with a distinctive historical consciousness, shaped by a sense of the transformational events of the late 1960s and early 1970s, events associated with their coming to maturity in a world changing rapidly in political and technological terms. We should also perhaps not overlook the impact of a rich nostalgia industry, drawing on the televised imagery of the era, which frequently reminds boomers of the happenings that have supposedly defined them.

The boomers are distinguishable from the silent generation in that the second world war is outside their living memory, but the legacy of that war was often profound for them — a phenomenon impossible to capture in a survey on “events.” The Moon landing, the Vietnam war and the Dismissal also figured prominently for the silent generation (ranked two, three and four, after the second world war); but this generation also ranked a panoply of events concerned with the monarchy (Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation and subsequent visits), nation-building and infrastructure (the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme, the Sydney Opera House), and technological change such as air travel and medical advances.

The boomers shared with gen X Australia’s America’s Cup victory of 1983 (ranked six by both, 15 per cent for gen X and 12 per cent for the boomers). The 2000 Olympics might have performed some of the same work for the millennials and gen Z (both 14 per cent), but it was nominated by even greater numbers of gen X, who seem to be particularly preoccupied with sporting spectacle and national esteem. Gen X appears to have been most affected by the period’s strains of cocky sporting and corporate nationalism — a winged keel generation, perhaps.

Gen X has some other distinctive features, too. It is the only generation that ranked the development of the internet — at seven (12 per cent). Unlike the two youngest groups, who are “digital natives,” gen Xers are old enough to recall a world before the web. They are also mainly old enough to recall the mass shootings of the 1980s, and rated the Port Arthur massacre at three, with 21 per cent nominating it in their top ten, and gun law reform at equal tenth (9 per cent). In the national top ten, Port Arthur was fourth, with 13 per cent. But when respondents were asked to nominate the single most significant event, the Port Arthur massacre came in third (5 per cent), with gun law reform seventh (3 per cent).

Economic vulnerability registered most strongly among millennials. The global financial crisis, which appeared in their top ten (12 per cent), possibly serves as an event conveying their concerns about issues such as student debt, job security and the price of housing. But the relative success of Australia in weathering the economic storms of recent years is reflected by the finding that just 8 per cent of respondents overall mentioned the GFC.

Social researchers have remarked on white Australians’ reluctance to discuss wrongs against Indigenous people. But the survey suggests that many Australians do see Indigenous experience as important in their history. When the responses to the top-ten question are grouped in themes, Indigenous issues are ranked sixth, with 24 per cent nominating events such as the Apology to the Stolen Generations of Indigenous children, the Mabo High Court decision on native title in 1992, and the 1967 referendum. In particular, the Apology has some purchase as a symbolic national event. It came in third overall, with 13 per cent, but the generational breakdown indicates that it was rated highly only among those younger than their early fifties. For members of gen Z — many of them at school when it was delivered — the Apology appeared defining, with more than a quarter mentioning it (27 per cent).

It is possible to agree that an event had a significant impact while disagreeing about the nature of that impact — whether it was good, bad or in between. The dismissal of the Whitlam government appeared in the top ten of Labor, Coalition and Greens supporters, but we can be sure that they do not see it in the same way. There were, more generally, significant areas of difference between supporters of the parties, even allowing for common ground. Labor supporters rated same-sex marriage slightly higher, and Greens supporters significantly higher, than 9/11. Coalition supporters had 9/11 first, and the Bali bombings, absent from the Labor list, was also in their top ten.

Labor supporters put the Apology to the Stolen Generations at number three, while Coalition supporters did not rate the Apology in their top ten at all. One Nation voters also omitted the Apology, as well as the Port Arthur massacre, and they rated same-sex marriage only at number seven: as many as 17 per cent nominated it as the event that had most disappointed them. This group seemed especially enamoured of Anzac Day commemoration, with 14 per cent nominating it as the event that made them proudest, and they had the Queensland floods at number six, expressing the strength of the party in that state and perhaps a sentiment about battling natural as well as social hardship.

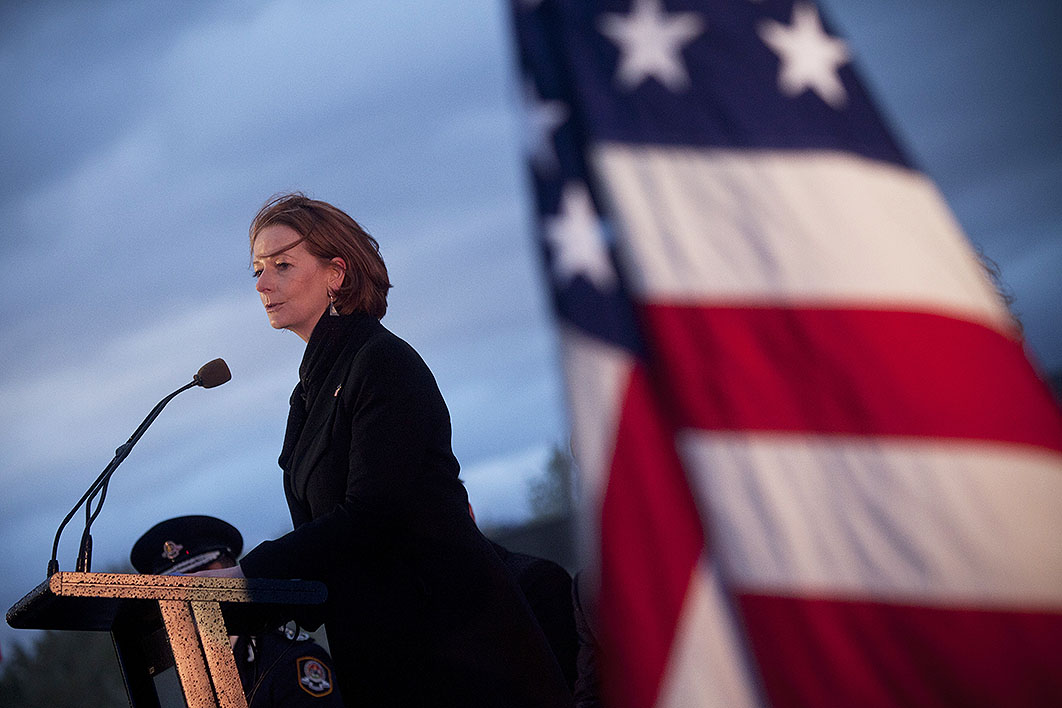

There are also some notable gender differences. Men mentioned the September 11 attacks (27 per cent) more than same-sex marriage (25 per cent); women mentioned same-sex marriage (35 per cent) more than 9/11 (27 per cent). Intuitively, this result seems to mirror participation rates in the 2017 same-sex marriage survey, which were higher for women than men. Women also ranked the Apology significantly more than men did — 17 per cent compared with just 9 per cent — while Julia Gillard’s election as prime minister came in at six for women (11 per cent) but did not figure in the top ten for men (4 per cent). In general, her election was not Australia’s “Obama moment”: 40 per cent of respondents in the Pew survey ranked Barack Obama’s election in their top ten compared with a mere 8 per cent of Australians mentioning Gillard.

Sometimes an event, because it is local or regional, has imprinted itself much more firmly in a particular state or city than elsewhere in the nation. The most spectacular example of this pattern is the Port Arthur massacre, which was mentioned by 32 per cent of the admittedly small Tasmanian sample, outranking both same-sex marriage (31 per cent) and 9/11 (29 per cent). Similarly, 19 per cent of the small Northern Territory sample mentioned Cyclone Tracy. The Lindt Cafe siege, which occurred in Martin Place, Sydney, was mentioned by 13 per cent of Sydneysiders, compared with the much lower national figure of 7 per cent.

And the same is true for some happier occasions. The Sydney Olympics were much more likely to be mentioned in that city (21 per cent) and in New South Wales generally (18 per cent) than by people living elsewhere (the national figure is 12 per cent). Western Australian residents were twice as likely as Australians overall to recall the significance of the America’s Cup’s (the successful syndicate was from that state). They were also more likely to nominate the mining boom than their fellow Australians further east.

The sample size for Indigenous-identified respondents was very small (forty), but there were some variations from the national norms in Indigenous selections. The most significant is unsurprising: 37 per cent mentioned the Apology, compared with a 12 per cent non-Indigenous figure. On the other hand, rural and regional respondents rated both the Apology and same-sex marriage lower than their metropolitan counterparts did.

One might have expected the issue of asylum seekers to have figured, perhaps in the form of a recognition of the Tampa crisis of 2001 as an influential historical event. In fact, it emerged only when people were asked about a time or event that has most disappointed them, topping this list with 8 per cent. The postwar immigration scheme was not mentioned in any top ten, perhaps not being recognised by respondents as an “event.” The end of the cold war is apparently regarded by Australians as none of their business.

Australians perhaps like to think of themselves as less insular than Americans, but 13 per cent in the US survey identified the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the cold war as consequential, ranking these momentous events eighth. In Australia, neither the end of the long postwar economic boom in the 1970s nor the rise of China registered as a landmark. Indeed, economic “events” barely figured in Australian top-ten responses. The 1983 dollar float, for instance, a favourite among politicians and journalists, had little resonance. Nor were there any signs of environmental issues, such as the saving of the Franklin River, in the top ten — not even among Greens supporters!

Women’s lives have been transformed in recent decades, but there are few gestures towards this social revolution in the data. The arrival of the contraceptive pill (1961) appeared in no one’s top ten, not even the baby boomers’, whose lives are usually seen to have been so shaped by it. Those under about forty did, however, nominate a moment that encapsulates the shift in gender politics: the election of Julia Gillard was ranked five by gen Z (15 per cent) and eight by millennials (10 per cent). Overall, 8 per cent of respondents included Gillard’s election as the first female prime minister, placing it equal tenth.

Historians might be puzzled by some of the results. Many events to which they commonly turn to explain the making of modern Australia figure barely or not at all. And contrary to the image of Australia as a utilitarian society whose people are concerned overwhelmingly with material issues and practical outcomes, respondents appeared to have a taste for the symbol, the spectacle and the landmark.

The survey reminds us that we live in a globalised world where big international events — such as the Moon landing and 9/11 — are recognised across oceans and borders as turning points in a shared history. All the same, Australians continue to find a place for the national and even the local, still recognising their own backyard as a place where history happens. •

The results of the survey can be found here.