“Humans – through our ingenuity, our commitment to fact and reason, and ultimately our faith in each other – can science the heck out of just about any problem.” Barack Obama’s recent words are refreshingly optimistic, and they don’t just apply to Americans. Earlier this year, Australian researchers made a crucial breakthrough in the fight against cancer; this month saw the unveiling of Australia’s first self-driving car, a technological feat that could transform lives for the elderly and prevent deaths on the roads. Standards of living continue to improve too, with Australia’s economy doubling in size, per capita, over the last forty years.

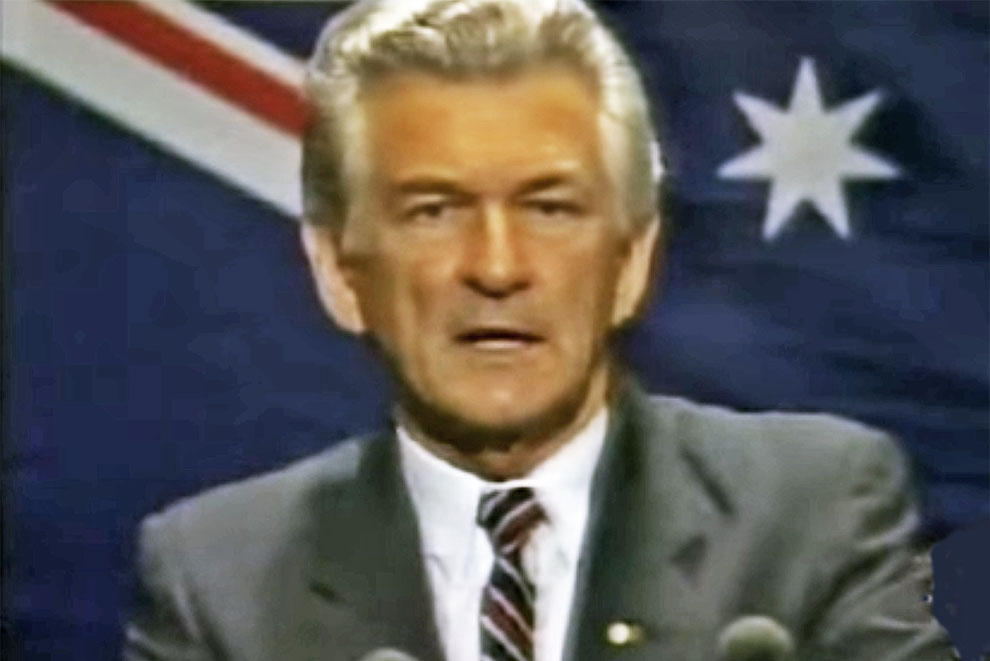

Yet this era of unprecedented progress has not extended to Australia’s social service sector. Almost thirty years after Bob Hawke pledged that no Australian child would live in poverty, over 730,000 children do just that. Learning outcomes in our schools are stagnant, particularly among disadvantaged students. Indigenous Australians continue to experience dire life outcomes, including an incarceration rate 14.8 times that of non-Indigenous Australians. Waves of progress have left some of our most important challenges largely untouched.

Much of the problem lies in a lack of focus on outcomes, with few incentives to use the most effective means when spending billions each year procuring social services. While companies are quick to use big data to sell us breakfast cereal, governments have been less adept at using similar tools to support vulnerable Australians. Data on the effectiveness of social programs is often limited and, unlike the information that informs investments on the stock exchange, there is no consolidated and transparent reporting of outcomes achieved by service providers to guide public investments. With tight budgets and great need, the same old approaches are not feasible options to address disadvantage.

Imagine a world where governments could purchase outcomes. They would identify high-need populations, fund tailored programs and measure the results: stable housing for people who have been homeless, for instance, or reductions in reoffending for people leaving prison, or improved learning outcomes from interventions in schools. Once those results were achieved, providers would be paid a price that reflected budget savings as well as social benefits. Funding would be linked tightly to sustainable improvements in people’s lives.

This future isn’t as far-fetched as it might sound. Pay-for-success contracting, or PFS, ties funding to the delivery of outcomes, rather than to inputs alone.

PFS is not new. For instance, nearly two decades ago, the Australian government created the first iteration of a PFS system to help unemployed people into work, currently known as Jobactive. This program has a $6.8 billion budget over five years, making it one of the largest PFS contracts in the world. Participating organisations, like Mission Australia, are paid only after their clients have found and kept a job. The system is far from perfect and hasn’t been rigorously evaluated; but compare it with the alternative where providers are paid for delivering training and career guidance (inputs and activities) instead of the desired outcome – employment. Which approach is most likely to get the results that taxpayers and government want?

Compared to traditional contracting based on inputs and activities, PFS has two strengths: it improves incentives and gives service providers greater autonomy. With the improved incentives under PFS, service providers are discouraged from activity for activity’s sake: training that doesn’t lead to a job, or out-of-home care for vulnerable youth without planning for a stable transition to longer-term options. Even the simple act of tracking the results of a program under PFS provides focus: what gets measured gets done.

Likewise, funding based on achieving measurable targets improves accountability. The goalposts are clear and governments are better equipped to assess success when contracts expire: the wheat can be separated from the chaff. Over the long term, more money will flow to higher-performing programs and organisations.

The autonomy that service providers enjoy under PFS also enables them to focus on the results they exist to achieve. By reducing or eliminating reporting requirements on inputs and activities, PFS gives providers the discretion to determine the best way to reach agreed targets. The relationship between government and providers evolves from compliance to collaboration. Rather than operating in a contracted straitjacket, people on the frontlines are free to respond to the specific context they face, using all the evidence and creativity they can muster.

PFS will not be appropriate for all sectors or solve all problems. It requires outcomes measurement that is not always possible. And PFS has its limits: funding reform is not a quick fix for all social problems, nor for the development challenges faced in parts of Australia. There are no silver bullets here. Like any system, poorly designed PFS can create perverse incentives, such as short-termism. But when it’s designed and used effectively, PFS can drive higher social returns from government spending.

Why, then, is PFS not the dominant paradigm of social service provision across Australia? Because doing PFS contracting is hard. Specifically, we see four main challenges:

1. Service provider funding needs: PFS creates a timing gap between costs incurred during program delivery and funding received, creating a cash flow challenge for service providers.

2. Obtaining sufficient political will: Risk-averse governments may be reluctant to apply PFS, particularly when it is difficult for voters to grapple with the effectiveness of social sector expenditure, and to build support for change.

3. Technically challenging procurement: Transitioning to PFS contracting involves determining outcome measures, setting targets, establishing outcome prices, selecting appropriate providers and evaluating whether outcomes have been delivered.

4. Data limitations: Often the outcomes of programs are not tracked, with a greater focus on easier-to-measure metrics, such as cost to serve and activity completion.

Social impact bonds and the transition to PFS

The good news is that governments and service providers are experimenting with new tools – including the much-hyped social impact bond, or SIB – to pay service providers for achieving desirable outcomes. SIBs are a type of PFS contract that uses private or philanthropic finance to bridge the funding gap that arises because services providers (typically non-profits) aren’t paid until results have been measured. As Mike Steketee described recently in Inside Story, financiers take on the risk of failure and are repaid by the government if and when targets are met. Two SIBs that prevent children entering out of home care by supporting families have been launched in New South Wales. Another fourteen are in development by state governments from both sides of politics to address social issues including homelessness, chronic health conditions, prison recidivism and substance abuse.

The bad news is that the buzz around SIBs often incorrectly centres on the role of the private sector, thus potentially setting SIBs up to fail. For instance, NSW premier Mike Baird has said that “rising demand for social services amid fiscal constraints has prompted governments to look at alternative sources of funding.” However, SIBs typically don’t expand the funding available for social services. Because private financiers won’t accept sustained losses, they will not add to total spending on social services in the long run. While governments benefit from paying only if the desired outcomes are achieved, this benefit is offset by risk premiums paid to financiers. Ultimately, governments still foot the bill and, in most cases, need to put money aside upfront.

Neither are SIBs primarily about using savings to repay investors. While theoretically plausible, these savings are typically too distant, diffuse and difficult to measure. Few social programs would receive funding if a positive financial return for government was the only metric. Governments sold on the idea of SIBs as “paying for themselves” are realising this is only a half-truth.

All of this noise obscures what will likely be SIBs’ primary benefit: accelerating the transition to greater use of PFS. Specifically, SIBs show promising signs of addressing several of the challenges for PFS expansion. Most directly, they address service provider funding needs (challenge 1) by providing a bridging cash flow.

SIBs have also demonstrated their usefulness as a political circuit-breaker (challenge 2). Tight budgets often leave insufficient funds for existing remedial services, making it difficult to reallocate spending from treatment to prevention. Any shift to prevention may be perceived as a budget cut, and the effectiveness of the new program may be questioned. Complicating the picture is the fact that preventative expenditure (rehabilitation for parolees, for instance) is often accounted for in different budgets from those recording the savings resulting from prevention (unemployment benefits; costs of crime). By linking funding to outcomes, SIBs can break down budget silos and appease sceptics.

SIBs have also been an effective tool for rallying a coalition of people and organisations across the public, private and philanthropic sectors to focus on impact. This increased attention has the potential to cut through the stasis in many of Australia’s social sectors. Would premiers, ministers and the media be so enthused by social sector procurement reform if SIBs, the private sector and “impact investing” weren’t part of the equation? This momentum is allowing SIBs to establish the preconditions for PFS, including a vital increase in data collection and measurement of results.

For PFS to expand, though, government will need more than SIBs. SIBs are small, expensive and hard to scale up. The world’s largest SIB, measured by success payments, is Uniting Care’s Newpin program, which reunites and improves relationships within at-risk families in New South Wales. But the program’s funding – $50 million over seven years – is dwarfed by the total annual Australian social sector expenditure of $395 billion, excluding income support.

SIBs also involve substantial transaction costs. Each of the sixty-plus SIBs around the world is underpinned by a tailored agreement between government, providers, financiers and evaluators. The two SIBs launched in New South Wales each involved almost 12,000 hours of preparatory work, an average of approximately six hours for each child in the program.

In short, as they are now, SIBs alone will never dramatically change the way Australian governments deliver social services.

Building on SIBs to expand PFS

Notwithstanding worthwhile efforts to standardise SIBs and decrease their cost, a much broader PFS system is needed for a dramatic improvement in Australia’s social expenditure. Specifically, government will need to build data collection and management systems, procurement capacity and political will. Fortunately, governments of all stripes are taking steps in the right direction.

There is growing recognition of the need for a more sophisticated procurement capacity (challenge 3). Initiatives such as Tasmania’s Funded Community Sector Outcomes Purchasing Framework and Queensland’s Outcomes Co-Design Framework are a good start. More work is needed, though, to turn the aspirations of these frameworks into practice.

Governments can make progress here by experimenting with hybrid contracting options. For instance, linking a small portion (5 or 10 per cent) of a program’s funding to positive outcomes can drive significant behavioural changes. Mindsets and technical skills also need to be developed; such a process has been supported elsewhere with pro bono support by organisations like the Harvard Government Performance Lab and Oxford’s GO Lab.

Australian governments are also investing in data collection and application (challenge 4). For instance, through its new “investment approach” to welfare, the Australian government has gained insights about those on welfare using fifteen years of data – an approach that could be used to price and track outcomes following interventions by social programs. At the state level, efforts to support better data sharing between governments and providers include the NSW Data Hubs and the Victorian government’s data sharing in response to the royal commission into family violence.

These efforts should continue, with an emphasis on creating incentives for providers to share data, including financial rewards and comparative performance data. In Seattle, for instance, a portion of government funding is tied to the timely collection of data, which is then used to compare performance across programs. Understanding the services delivered and the results achieved will help to fix the right price for outcomes, set appropriate targets and ultimately fund the highest-performing programs.

Zooming out, progress in expanding PFS is constrained by the relatively small group of people and organisations advocating for a more effective social services sector in Australia (challenge 2). In the United States, strong national leadership has come from the Obama administration through the Social Innovation Fund, which has funded PFS technical assistance and investments in data, and has experimented with alternative funding mechanisms. Philanthropy, too, has played a catalytic role. Results for America and Bloomberg’s What Works Cities initiative, for instance, have partnered with governments to enhance their use of data and evidence to improve services. They have also played an important role in supporting the development and successful passage of PFS-specific legislation through Congress. Similar leadership in Australia is sorely needed.

Innovations in the private sector and elsewhere are driven by clear objectives: the thirst for profit, customer satisfaction or even finding a cure for cancer. Likewise, PFS provides government with the opportunity to provide a North Star in the social sector, defining desired outcomes and rewarding achievement. SIBs alone will not get us there; they will form one part of a broader PFS ecosystem. Unless they are seen that way, they risk being treated as little more than a passing fad.

Obama is right; humans are capable of tackling any problem. With the right ingredients – fit-for-purpose funding models, procurement capacity, data and political will – Australian social services should be no exception. PFS provides the means for Australians who are most in need to benefit from this age of extraordinary progress. •