The authors of Labor’s Defence Strategic Review have done their job and dispersed to where they’ll find receptive audiences — former foreign affairs minister Stephen Smith to London to present his credentials as high commissioner to the Court of St James’s, former defence force chief Angus Houston to speak at Washington’s Center for Strategic and international Studies.

Along with Honolulu, those were the only places the two visited outside Australia to seek views on the strategic picture. Not Tokyo, nor New Delhi, Singapore, Jakarta or Port Moresby.

In their wake, many observers are mystified by the relationship between the Defence Strategic Review and Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, a decision sprung on voters in September 2021 by Scott Morrison and endorsed with less than a day’s study by then opposition leader Anthony Albanese.

The parts of the Smith–Houston review curated and released by defence minister Richard Marles confirm that it didn’t question the Australia–United Kingdom–United States agreement, known as AUKUS. If Smith and Houston discussed what role the extraordinarily expensive submarines will actually perform, they did so in the still-classified parts of their review.

Press gallery defence reporters have already started the game of trying to winkle out of anonymous sources the scenarios that might have been canvassed by the review, including the defence of Taiwan and the lodging of Chinese forces in the Solomon Islands. Presumably Smith and Houston looked at the possibility that China would strike at Australia in the event of a Taiwan conflict in order to disable Pine Gap, North West Cape and other US war-fighting installations.

Sydney University historian James Curran, newly appointed international editor of the Australian Financial Review, raises a scenario that probably wasn’t mooted: the cutting of Australian shipments of iron ore and other commodities to China. “Such a devastating blow to Australia’s economy is never mentioned in these strategic reviews — economics and national security remain in uncooperating silos,” Curran writes.

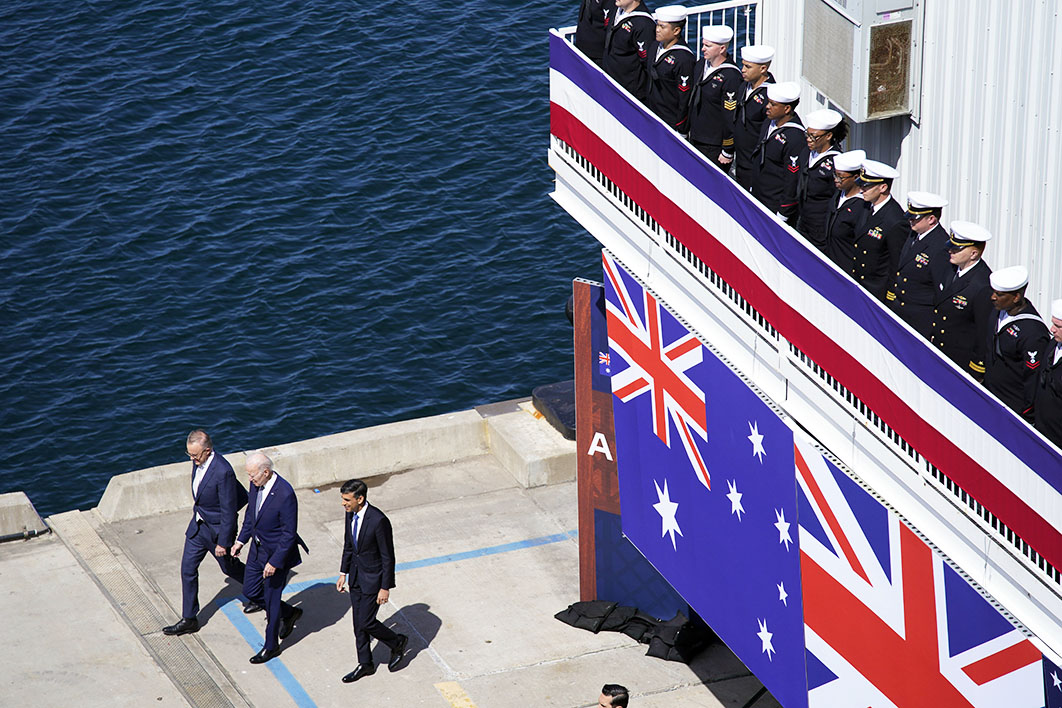

As for the text that was released, many commentators have detected unsupported assertions and logical leaps. Most glaring perhaps was the reference to an “AUKUS Treaty” when the tripartite agreement was simply a joint statement by the three leaders at the US navy’s San Diego base in March.

Neither Morrison nor Albanese has presented the agreement to parliament for explanation and debate, let alone set in motion the ratification required of a treaty. Nor have the other two governments to their legislatures. Both Joe Biden and Rishi Sunak face elections next year and could be gone — in America’s case, possibly replaced by Donald Trump.

Those elections aren’t the only stumbling blocks. Washington’s agreement to sell between three and five Virginia-class submarines to the Australian navy from the early 2030s could be contingent on its own navy managing to step up production of these hunter-killer vessels, known as SSNs.

The Americans currently have about fifty SSNs, well below their force level goal of sixty-six. They hope to increase production of new Virginia-class boats to two a year, but the current rate works out at about 1.3 boats per year. At the AUKUS ceremony, it was disclosed that Australia would be investing perhaps $3 billion in helping the two US submarine yards speed up work, but the impact is likely to be quite marginal.

As it is, the US navy’s thirty-year shipbuilding plan shows the SSN force reaching the sixty-six-boat target in 2049 at the earliest. So the sale to the RAN will subtract from the American fleet — unless, of course, the vessels effectively operate as part of the US navy’s Indo-Pacific fleet. Marles has denied any such agreement or condition; veteran defence-intelligence analyst Brian Toohey scoffs at such assurances.

The three to five Virginia-class subs provided to Australia will already be about halfway through their thirty-year reactor life, and are seen as a holding capability until a jointly designed successor to Britain’s current Astute-class SSNs can be built. The first of those future submarines will be laid down in the early 2030s and delivered — from Barrow-in-Furness in England for the British navy, and from Adelaide for the Australian navy — in the 2040s.

But not from the American yards, despite the promised US contribution to the design. The US navy doesn’t want them, and is instead persisting in developing its own successor to the Virginia-class, known as the SSN(X). This raises an obvious question: having inducted an American boat into its fleet, why wouldn’t the Australian navy stick with the Americans for its successor?

It also brings us to perhaps the most perplexing thing about AUKUS: the involvement of the United Kingdom. Why did Morrison need to get his British counterpart Boris Johnson involved in approaching the Americans? Even if the Australian navy was inclined to Britain’s Astute-class, an American sign-off was required for the transfer of its reactor technology, a closely held US secret.

The proposed joint AUKUS submarine thus hangs on Britain, a declining power in great economic disarray. The Tories must be quietly chortling at having roped in the Australians to subsidise their naval plans. Adding to the puzzle is the post-politics job Morrison is said to be negotiating with a British defence group.

Australia’s close strategic alliance with the United States is generally accepted in our region. Japan and South Korea have similar alliances, Singapore and Thailand more tacit ones, and India and Vietnam a growing closeness. To revive close strategic ties with Britain undercuts decades of diplomacy designed to project Australia as an authentic regional partner. Surely the Australian navy has moved on from pink gins?

Meanwhile, the Smith–Houston review has rearranged our defence capacity around the nuclear submarines and their projected $368 billion cost. From a “balanced” force with a bit of everything, it is to become “focused” on projecting power further from Australia.

Ships and aircraft are to be equipped with longer-range missiles, their stockpiles built up by local production rather than imports. The army will also be more of a missile force, with the US artillery–missile hybrid known as the HIMARS extending its strike range to 500 kilometres and a greater amphibious capacity to move forward against threats.

To pay for this, the army loses a second battery of heavy guns, and its planned new fleet of South Korean– or German- designed, locally built armoured personnel carriers will be cut from 450 to 139, enough for a single brigade. At a mooted cost of $27 billion — averaging $60 million per vehicle — the project did seem absurdly inflated, but Smith and Houston mentioned no other means for protecting soldiers.

Nor do they discuss the fate of the army’s heavy tanks — its fifty-nine M1 Abrams and the updated replacements ordered by Morrison’s government. Perhaps a contribution to Ukraine, to be announced by Albanese when he is a guest at the NATO summit in July?

Accompanying the partial publication of the defence review has been some spin-doctoring designed to create the impression that the longstanding “Defence of Australia” doctrine, which has prevailed since senior defence official Paul Dibb’s 1987 white paper, was designed to deal only with low-level threats and is consequently obsolete. Actually, under the earlier doctrine Australia possessed quite an extended punch using air-refuelled F-18 strike aircraft and the six Collins-class conventional submarines.

Former army chief Peter Leahy is one who believes that Smith and Houston’s “all new” doctrine is really Defence of Australia Extended. “Its authors boldly state that it is not ‘just another defence review,’ but that is exactly what it is,” writes former defence official Hugh White, who wrote a defence white paper in the Dibb tradition in 2000.

Members of the hawkish commentariat, meanwhile, are apoplectic at the government’s failure to back with big money the review’s dire warnings of rising threats and a defence force “not fit for purpose.” They point out that many of the proposed new capabilities had been announced over the past three years. Some of them point to the government’s post-review backpedalling on capabilities already in the works. A committee headed by a retired US admiral will see whether the navy’s surface fleet needs all of the nine Hunter-class large frigates to be built in Adelaide, or a larger number of smaller corvettes.

“The Defence Strategic Review is worthless unless Defence stops deliberately dragging the chain,” declared the Australian’s foreign editor, Greg Sheridan. “Strategy without dollars is just noise.” For Peter Jennings, former director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the review was “a collection of unfunded compromises and shocking policy gaps.”

The funding gaps are not just directly in the military domain of the “national defence” strategy propounded in the review. Referring to increasing calls on the defence forces to help out in natural disasters caused by climate change, Smith and Houston suggest a separate emergency agency. They point to Australia’s small reserves of fuel and dwindling refining capacity, declaring that the energy industry should be directed to come up with remedies.

A different criticism of the review comes from White. “The choice we face today is whether to build armed forces designed to help the US defend its strategic position in Asia against China’s challenge and preserve the old US-led order,” he writes, “or build forces that can keep us secure as American power in Asia fades and a new order dominated by China and India takes its place.”

We can’t do both, White adds, “because that pulls our force priorities in very different directions.” On the one hand, AUKUS was all about supporting the United States against China in Northeast Asia. On the other hand, the defence review — despite its emphasis on the US alliance — focuses on the defence of the Australian continent and its approaches.

At points, the review doesn’t seem sure which way to jump. As White observes, it argues that Australia’s forces must be able to deter “unilaterally” but then, in the same paragraph, it says this can only be achieved by working with the United States. “Australia’s nonchalance about this,” says White, “is typified by the reckless gamble of entrusting our future submarine capability to the impossibly protracted, complex and risky AUKUS nuclear program, when much faster and more cost-effective conventional options are available.”

The Lowy Institute’s Sam Roggeveen sees “tension and ambiguity” between the review and the AUKUS plans. “If the navy should be ‘optimised for operating in our immediate region,’ why do we need submarines optimised for operating thousands of kilometres north of it?” he writes. “Why is the RAAF Tindal air base being modernised so the United States can operate long-range bombers from there?”

A deeper contradiction looms for Peter Varghese, the former secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and director of ONA, Australia’s top intelligence assessment agency. Talking to James Curran for the AFR, Varghese agreed that Australia should stick with the United States as the most important player crafting a new balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region.

“Whether we can sustain this position without handcuffing ourselves to the maintenance of US strategic primacy is the big challenge for our strategic policy,” Varghese said. “A balance of power which favours our interests and adopting US strategic primacy as a vital Australian interest are not the same thing, and it would be a mistake to conflate them.” •