Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. In post-industrial society the range and quantity of skills and knowledge needed in the workforce are growing as rapidly as their half-life is shrinking. Education is the main means of acquiring and benefiting from skills and knowledge. More education brings better income and job prospects, better health, lower crime rates and more civic engagement. Education is an investment in the next generation and in the nation’s future. Building education is building the nation’s stock of human capital. If we don’t invest, we will fall behind those countries that do.

That version of the story comes from Deloitte Access Economics via Universities Australia, which commissioned Deloitte to “analyse the contribution that universities make to Australia’s economic and social prosperity.” But we’ve all heard other versions, and some of us have been hearing various combinations of lobby group spin, political guff and complaisant economic theory ever since 1964. It was then that the federal government’s Martin committee, advised by the OECD, which was itself advised by a small group of American economists, abruptly abandoned previous educational rationales and declared that “economic growth… is dependent upon a high and advancing level of education” and that education should therefore be regarded as “an investment which yields direct and significant economic benefits through increasing the skill of the population and through accelerating technological progress.”

This explanation of growth – the “human capital” argument – is not altogether wrong, as either explanation or prescription, but it is radically incomplete. What it overlooks is the incessant struggle of occupational and social groups, families and individuals to acquire government-backed credentials and the many social and economic advantages they bring. That struggle has had significant consequences for the size, shape, culture and outcomes of the education system, most of which have been concealed rather than understood by human capital theory. In other words, the relationship between education and economic growth is as much social, political and ideological as it is economic.

If we put the social and the political and the ideological back in, the whole picture changes. We can see why education has not just grown to meet the expanding needs of the post-industrial economy, but has exploded like an airbag.

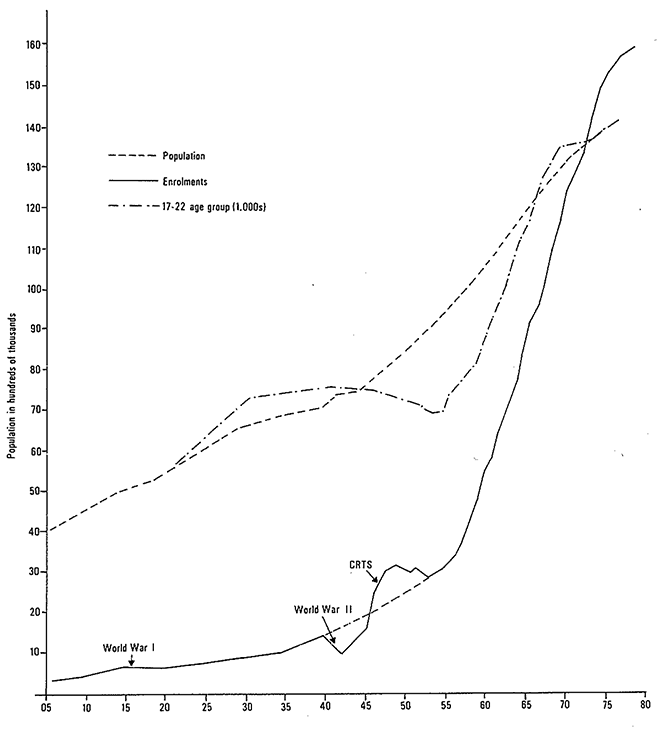

Growth in student numbers at Australian universities, 1906–80, compared with growth in national population

Note: The solid line shows the number of additional enrolments over time (with a dotted section 1940–55 to smooth wartime and postwar effects); the dotted lines show the number of additional members of the national population, total and in the age group 17–22, over the same period. CRTS refers to the postwar scheme that enabled returned soldiers to enter higher education.

Source: D.S. Anderson and A.E. Vervoorn, Access to Privilege, ANU Press, 1983.

In the thirty years from 1952 – in less than the working lifetime of a teacher, that is – the number of students in schools more than doubled, in technical education tripled, and in higher education multiplied by no less than twelve. As well as growing much more rapidly than the population, education outpaced both the workforce as a whole and the highly skilled workforce. Between 1980 and 1990, the proportion of the workforce with post-school qualifications rose from 38 to 48 per cent, while the proportion in skilled occupations changed not at all. Then, over the twenty-five years from 1989 to 2014, the proportion of the working age population with a bachelor’s degree or higher tripled, while the proportion of professionals in the workforce rose sedately, from 15 per cent to 22 per cent.

With social, political and ideological realities back in the picture we can also understand why a vastly expanded system, which has brought many benefits to many people, has nonetheless been a disappointment. We can see why governments have been on a policy treadmill, lubricated by an overweening and inadequate theory, tackling the same old problems over and again in the belief that more and yet more education will make them go away. The result is an increasingly bloated and self-serving university sector; a demoralised and marginalised VET (vocational education and training) system; stubborn inequalities in educational opportunities and outcomes; persistently high proportions of school leavers and adults who, as the euphemism goes, “lack the skills for full participation in contemporary society”; chronic grumbling by employers about the “job readiness” of new employees; and, for many of those on the receiving end of it all, an ever-lengthening educational experience of variable quality, ever-increasing competitiveness and ever-increasing costs.

ORIGINS

In August 1984, federal and state governments agreed that nurses should be trained not in hospitals but in colleges of advanced education. At a stroke, the higher education system was committed to grow by 18,000 places over a decade. Like the nurses who had agitated for change, the governments justified the new rule by pointing to the growing complexity of nurses’ work arising from advances in medical science and technological change in the health industry. These new conditions of labour, they argued, required a more extended and demanding preparation of nurses, and it could not be provided in hospitals.

In fact, the governments had bowed to pressure rather than reason, and acted against the advice of the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission. Under a new generation of militant leaders, nurses’ unions had turned to bitter industrial action and confrontation. But their discontent grew not out of any increase in the sophistication of nurses’ work but out of something like the obverse, a lack of change in its social and financial conditions. Nurses were tired of authoritarian hospital managers and matrons and of being treated as domestic help by doctors. Their salaries had fallen far behind those of comparable occupational groups. Huge wastage rates testified to the failure of the nurses’ representatives to defend legitimate workplace interests. The new leadership saw very clearly that the only way to solve the problem was to get credentialled.

The nurses didn’t invent this strategy. Indeed the first of many precedents was established in their own industry, by the doctors, in a complicated process that extended over almost a century from the 1850s, when the infant University of Melbourne established Australia’s first medical course. The campaign involved governments, occupational registration authorities, hospitals, employers and practitioners in both England and Australia. By its end, the medical practitioners had managed to bring together three elements to form a new molecule: the medieval institution of the guild, through which occupational groups staked out an exclusive claim to the exercise of a special skill; the newer mechanism of an educational credential, attesting to the consumption of an arcane body of knowledge; and the bureaucratic state, increasingly concerned to regulate, particularly on matters of public health and safety.

The doctors’ efforts overlapped with similar campaigns by architects, accountants, lawyers and engineers. Of these, the engineers’ was the most important and significant. Unlike architects, accountants and lawyers, but like many other occupational groups, most engineers were employed by big public and private corporations wedded to the existing “pupillage” and “workshop” system of training and the relatively modest salaries that went with it. In a campaign extending over decades, the engineers struggled to organise themselves around “the fundamental principle of definition by qualification”(emphasis in the original), as Brian Lloyd, a past president of the Institute of Engineers Australia, put it.

The engineers hounded their employers all the way to the High Court. In June 1961, a signal day in their history (and that of Australian credentialism), the court determined that “the functions undertaken in employment as a professional engineer were described unambiguously in terms of the qualifications needed to carry them out.” As Lloyd reports with satisfaction, the decision “placed the Profession of Engineering on a new and much higher plane of status and reward.”

As the engineers were slugging it out with their employers an even larger group was attempting to follow their example. The teachers’ genteel “associations” were being transformed into militant unions demanding higher education qualifications and the status and remuneration that came with them. The teachers, in turn, set an example for the nurses, and for dozens of others, including, most recently, early childhood teachers.

Apprenticeships had long provided “definition by qualification” for some working-class men; from the 1960s on, one mid- or lower-tier occupation after another joined the push for credentials, from childcare workers and private detectives to dental prostheticians and jockeys. In the late 1980s and early 1990s these and many other claims were advanced on behalf of myriad less powerful occupational groups by the indefatigable John Dawkins and his close adviser, former union heavyweight Laurie Carmichael. Dawkins’s “skills agenda” included an Australian Qualifications Framework that defined a hierarchy of occupations and matching qualifications all the way from certificates 1, 2, 3 and 4 to diplomas and degrees, and then up to the highest of ten rungs, the research doctorate.

As ever more occupations and employees got a foot on the ladder, those who were already there took care to maintain relativities. Many sought higher and/or longer and/or more specialised courses of study and qualification. Thus, the teachers claimed successively three-, four- and now five-year minimum courses of study, on top of which they became big consumers of postgraduate study. For accountants, membership of either of the two professional bodies demands a four-year degree followed by a program combining supervised employment with further study and examinations.

Many occupations have metastasised into a series of specialisations, most requiring a “post-initial” qualification. In 1957, postgraduate coursework students comprised just 3.5 per cent of enrolments; by the mid 1990s, in the wake of the Dawkins reforms, the figure had multiplied more than three times, and is now around 26 per cent. Increasingly, a second or third undergraduate degree is another route to the same destination – an existing higher education qualification has become the fastest-growing basis for admission into undergraduate courses.

The number of years of study required to acquire full professional status has increased correspondingly. To take the case of medicine again, the first graduates of Melbourne’s medical course were practising in their early twenties. Medical specialists are now often well into their thirties before they gain the coveted “membership,” and general practice has itself become a specialisation. While an identifiable and often complex group of skills and knowledge provides the grain of sand for a specialisation, it is the interests of those who control access to and use of that skill and knowledge that make the pearl grow.

Maintaining relativities also requires constant patrolling of boundaries and protection of nomenclature. Thus, the engineers have struggled against “alternative” entry routes and terminological hijackers such as “sound engineers” or even “automotive engineers.” In a moment of hubris the nurses talked about achieving parity of esteem with the doctors, a bid the doctors extinguished just as firmly as they have kept “complementary medicine” on the margins and other “health professionals” in a subordinate position. The teachers have had to fight on two fronts: against low standards of entry to mainstream courses, and against the recent arrival of an alternative to the mainstream, the Teach for Australia program. Some of the many groups engaged in this ceaseless struggle (nurses and electricians, for example) achieved the holy grail of closely regulated occupational closure. Others, such as the teachers, got close, while still others managed only nominal regulation or, as in the case of carpenters, gradually lost what closure they had.

The scramble among occupations for “definition by qualification” triggered a similar kind of scrambling among the institutions from which these credentials could be obtained, and within their constantly expanding customer base.

As in the case of occupations, the competition and elbowing among education providers and education consumers started at the top and worked its inexorable way downwards. When the second world war ended, Australia had just six universities, one in each of the capital cities. Only two decades later, there were fourteen, and these were joined by the “colleges of advanced education,” or CAEs, which swallowed up the old teachers’ colleges and technical institutes. In another blink of an eye the CAEs became universities too, which set off a scramble among the real universities.

First, the long-established universities formed the nucleus of the “Group of Eight,” with a view to staying at the top of several pecking orders: research; the professional and time-honoured disciplines; postgraduate and double degrees (rather than mere bachelor programs); and high cut-off courses for high-scoring students. Then the universities that were real but nonetheless excluded from that group formed an alliance of “innovative” universities, while the old institutes of technology became the Australian Technology Network, and the rump, mostly based on teachers’ colleges in the suburban and regional fringes, became “equity” institutions. Now they, in their turn, are pressed from below by TAFE colleges and private VET providers that have won from government the right to offer bachelor’s degrees, once the exclusive prerogative of universities.

In this lengthening, closely defined and tightly regulated pecking order, research output has become the key determinant of position. In 1938 there were just eighty-one research students in Australia. Now there are more than 60,000 of them, heavily concentrated in institutions that had a head start and which routinely siphon resources from teaching to maintain it.

There is (contested) evidence to suggest that the biggest beneficiaries of this research are not (as the universities like to say) “the economy” or “the nation” but rather the researchers themselves and the universities that whip them on in the race for a place in international league tables.

Overlaying the development of a hierarchy of institutions are more complicated patterns of positioning among courses and credentials. Here, three considerations interact: the level of the course, the status of the occupations to which the course and its credential apply, and the status of the academic disciplines concerned (“pure,” “rigorous” and old, rather than “applied,” discursive and new). Australia has developed a kind of currency that registers the net effect of these many variables at any one time. A glance at ATARs (the Australian Tertiary Admissions Ranks) – adjusted for fudging and fibbing – reveals how Murdoch stands in relation to James Cook, how law at Melbourne stands in relation to law at Flinders, how law in general stands against engineering, how physics or economics compares with sociology or business studies, and how any of these are faring now compared with a year or a decade ago.

As the number of groups using educational credentials to defend or advance their position increased, and as the numbers of providers and courses grew to accommodate them, the credential system spread its net over an increasing proportion of the population. In research conducted in the late 1970s, my colleagues and I had a privileged view of this constantly advancing frontier. Our fieldwork included long conversations with two groups of fifteen-year-olds and their parents and teachers, one group in mainstream government high schools in working-class districts, the other in high-fee private schools. In the latter we were struck by the number of girls determined to “go to uni” and by the encouragement they were getting from their schools and families, even though only a few of their mothers were themselves graduates, and most of their schools had long concerned themselves mainly with preparing girls for the marriage market. In the former, parents and students alike were acutely aware that “you need to stay longer at school these days,” but more as a form of defence against a deteriorating youth labour market than in order to “get on.” In all minds, including the teachers’, going to university was exceptional.

Now, three decades later, going to uni has a cult-like force. Ever-increasing numbers have been drawn into a single millrace via the elimination of the technical high school system and the marginalisation of the “school-based vocational programs” that were supposed to replace them, and by the articulation of VET and higher education credentials.

Upper secondary students by pathway type, mid 1990s

Created by Richard Sweet from data in From Initial Education to Working Life: Making the Transition Work (Table 2.2, page 170), OECD, 2000.

Being “first in the family” to go to uni, once rare, is now so common that in a generation or so it will be rare again. Females outnumber males in higher education, and working-class schools compete on the number of their Year 12s who achieve the dream. The ATAR is, for most young people, a brand on the forehead. For those suited to the particular form of learning in which this race is conducted, the question is no longer one of getting into uni, but one of which course in which uni. The rest must settle for second or third best, or try again later. Much the same can be said of occupational groups.

As an increasing proportion of occupations and a growing share of the population have been drawn into the competition for credentials, a vast industry has been constituted. Around seven million of Australia’s twenty-four million people are now engaged in one form or another of education and training – approximately 6.5 million school, VET and uni students, plus half a million or so teaching and administrative staff. In sheer numbers participating, education and training has a larger headcount than the four biggest industries (health, retail, construction and manufacturing) combined. It is, by that measure, more than half the size of the entire workforce.

This industry is now so large and so labour-intensive that a substantial fraction of its efforts is devoted to feeding itself. A recent projection suggests a growth by one-third in numbers of university qualifications in the ten years from 2015, concentrated in five industries. At the top is education and training, which accounts for nearly twice as many additional university qualifications as its nearest rival (healthcare and social assistance), and more than professional, scientific and technical services, public administration and safety, and financial and insurance services combined.

CHARACTER

To note that credentialism is at work in and through formal education and training is not to suggest that they provide nothing but credentials, or that they are simply the means by which individuals and groups clamber over each other in the struggle for the best seats on the gravy train, or to avoid missing out on a seat altogether. (Nor is it to suggest that education and/or credentialism are the only arenas in which such struggles are conducted.) Formal education and training does provide, among other things, economically useful skills and knowledge. It does this, of course, to widely varying extents and widely varying degrees of efficiency, as can be seen by comparing a first degree in dentistry, for instance, or a plumbing apprenticeship with a PhD in education or an MBA.

Nor is it to suggest that credentialism is simply the sum of the actions of individuals – a teacher enrolling in a PhD, for instance, or a manager studying for an MBA in pursuit of career advancement – or the sum of the activities of occupational groups in search of “definition by qualification.” As the pioneering example of medicine illustrates, occupational ambition is a crucial element in the compound, but so too are the state’s need and willingness to regulate, and the power of educational institutions to grant or withhold credentials according to the quantity of product consumed.

Just as capitalism is much more than what happens on Wall Street, so credentialism includes institutions and interests, ideas and culture. Increasingly, credentialism’s motive force has come from governments, which have not just responded to demands for “definition by qualification” but also effectively created them. They have done this by using these definitions as the key component in their regulation of many areas of work, and even intervening in the organisation of work (as the Hawke government did when it became involved in “award restructuring” and introduced the Australian Qualifications Framework).

While credentialism does contain its own ratchet-like logic of expansion, it is not independent of circumstances. Credentialism is triggered by economic and technological change, and is in constant interaction with them as well as with general levels of economic prosperity, security and expectation, and with the policies of government. Hence, the merely incremental advances in education and credentialling between the first and second world wars, and their exponential growth in the postwar years. Hence, also, very different rates of growth in education in the Fraser years and during the Dawkins boom. Credentialism is at work in most areas of economic life, but is more influential in some industries (health, for instance) than others (such as retail), in the public sector than the private, at higher-level occupations than lower, and in mid-sized and large organisations than small.

The education industry, like any other, comprises interests – sectors and levels, employers and employees, clients and providers. They often compete and sometimes clash, but are united in the claim that education is good, and more education is better. By extension, the more people engaged in acquiring more credentials, the better.

To that end, almost all of these interest groups have followed the lead provided by the Martin committee in 1964, taking economics and its human capital theory as the authoritative endorsement and vehicle of their claims. That is why Universities Australia hired Deloitte to make its case, and why that case is as it is: “universities embody social, economic and intellectual resources which combine to generate benefits on a local, national and global scale…” University graduates achieve “higher labour force outcomes” and, as is “well established,” a large part of that “is due to formal education.” Indeed, says Deloitte, Australia’s GDP is 8.5 per cent higher “because of the impact that a university education has had on the productivity of the 28 per cent of the workforce with a university education.” And while a university education “has been empirically demonstrated to be positively associated with improved health outcomes, quality of life and a range of other social indicators,” it is nonetheless “the broader society that is by far the greatest beneficiary.”

Governments are always the target of that argument, and are often – need and circumstances depending – its exponents as well. The case put by the Rudd government’s Bradley review (2008) to justify a “demand-driven” higher education system might have come from Martin fifty years before, or from any number of ministerial speeches in between. “Developed and developing countries alike accept there are strong links between their productivity and the proportion of the population with high-level skills,” it says. Australia is falling behind. If we are to “compete effectively in the new globalised economy” we must commit to “both structural reform and significant additional investment” as a matter of urgency. “We must increase the proportion of the population which has attained a higher education qualification,” it insists, well into a period (1989–2014) in which, as we have seen, the proportion of the working-age population with a bachelor’s degree or higher tripled. Credentialism has managed to make itself part of the taken-for-granted common sense of the age.

CONSEQUENCES

Credentialism is a source of many of the problems in the education and training system, and many of its limitations, but it is by no means an altogether bad thing.

Perhaps its most far-reaching benefit has been in supporting the massive expansion in numbers of groups and individuals given access to an extended education. Many of those involved in the struggle for “definition by qualification” saw their campaigns as a struggle for equality, and they were right to do so. The successful demand by teachers, nurses, engineers and many other occupational groups for higher qualifications has provided millions of young people from modest circumstances with a substantial expansion not just of opportunity but also of experience and knowledge. Not all get the best, of course, but getting an extended education is usually better than getting a short one.

This has helped to make a less mystified and mystifying society, and a less excluding one. It has helped to draw most migrant groups into the social and economic mainstream, and contributed to the entry of women into a wider world (particularly important given their virtual exclusion from trade apprenticeships). In 1950 there were just over 30,000 students in Australian universities, of whom only one in five were women (and even that was good compared with the proportion of female academics). In the course of a single lifetime, numbers have multiplied more than thirty times while the proportion of women among all higher education enrolments has almost tripled.

Credentialism also secured the link between social practice (medicine, engineering, teaching, the law and so on) and science, reason and humanism. In particular, the involvement of Australia’s infant universities in occupational training and certification ensured that they would follow the example of the English dissenting academies (notably the University of London) and Scottish universities rather than of Oxbridge. That gave the occupations concerned access to forms of knowledge that could not be generated within the occupations themselves. Again, medicine and medical training are particularly illustrative and important; as late as 1952, no less than a quarter of all university graduates were graduates in medicine.

And, finally, “definition by qualification” has provided many members of the workforce, employees and self-employed people alike, with the means by which they could exercise a measure of control over the content, and the terms and conditions of their work, and with an acknowledgement of its value. And even if that has involved a certain amount of conspiring against the public, as Adam Smith alleged, it has also provided the public with unprecedented levels of defence against incompetence, malpractice and snake oil.

Then there is the other side of the ledger.

Credentialism might be very good at expansion, but more education, and more opportunity for advancement through education, does not necessarily bring more equality. Credentialism is a zero-sum game, a striving by occupations, by educational providers and consumers, and by social groups for “positional advantage.” Those with the greatest social and cultural power are of course best placed in this struggle for positional goods. The opportunity is there for all, but it is heavily contested. In effect, those higher up the ladder tread on the fingers of those below. The position gained by one cannot be gained by another; indeed, if one individual or group or occupation or institution moves up, another moves down. Educationists and politicians like to talk about education’s ladder of opportunity, but have less to say about its snakes.

Most Australian eyes focus on the social-distributional aspects of these struggles – the extent to which where you start out determines where you end up. Thus Bradley, following a long tradition extending back through the Karmel Report (1973) and beyond, proposed special measures for “those disadvantaged by the circumstances of their birth: Indigenous people, people with low socio-economic status, and those from regional and remote areas.”

On this score the news is mixed. To the extent that the culture of a group drawn into the expanded education system is of a kind that makes its members willing and able to do what formal education institutions want them to do, they will fare relatively well. That is why women and many immigrant groups have been able to climb the educational ladder and enter the economic and social mainstream. Hence, also, the relative failure of many local-born working-class men, and some migrant groups.

Fairness of access to rungs on the social ladder via education does matter, but the length of the educational ladder, the proportion of the population to be found on its various rungs, and the learning that does or doesn’t come with each level – all these matter more. That those with at least one tertiary-educated parent are more than four times as likely to get a tertiary education as those without is bad. But that some get twenty years of the best that the system has to offer while others get ten of the worst, and that the latter are those who really need the extra help, is worse. At the top, the double-degree holders inhabit the dreams of “innovation strategies”; at the bottom, scarcely a trickle of learning arrives. As noted earlier, a recent international study of adult literacy and numeracy found that around half of Australians aged between fifteen and seventy-four struggle to use and comprehend basic writing and numbers.

What is true of educational experience and outcomes is also true of education’s other consequences. Calculating the “income and employment premium” of qualifications is a dark art, but it is clear that the relative premium attached to a university degree is much higher than to a diploma, and that in turn to a certificate. Astonishingly, in some lower-level occupations, trainees who complete their courses actually earn less than those who do not. And down there at the bottom you don’t just get a lower rung on the salary and status ladder. You fall off. It is true, as politicians like to tell unemployed or “disengaged” young people, that the way to get a job is to get a qualification, but only if you get a better one than your peers.

Credentialism both exaggerates and mystifies the competitive element in education. It compounds the tendency to give more to those who are good at formal learning than to those who aren’t. Credentialism works on the trickle-down principle, in educational opportunity, provision and outcomes, and in their consequences in the labour market and life. Its rhetoric of opportunity and individual responsibility obscures the fact that anyone can learn if they get the right help. It also obscures the fact that the “post-industrial economy” wants more skills and knowledge at the top, yet at the bottom, left to its own devices, it doesn’t even offer a job.

A second entry on the negative side of credentialism’s ledger is its impact on costs.

Increasing numbers consuming increasing amounts of education create an increasing need for someone to pay. In 1960 prime minister Robert Menzies wrote to Leslie Martin, the man he had recently appointed to chair a tertiary education review, to point out that the government was “by no means sure that this state of things – more and more students requiring proportionately more and more outlay – can proceed indefinitely.” What Menzies saw as a problem for government, subsequent governments have turned into a problem for consumers as well, first by cutting back on what the consumers get, and then by making them pay.

Between the late 1970s and the turn of the century, the annual government spend on each higher education student, in real terms, just about halved. Over much the same period, the proportion of higher education revenues coming out of (domestic) student pockets soared from nil to 11 per cent (1989) to 19 per cent (1999). HECS and its “income-contingent loans” were an inspired alternative to the reimposition of fees, but the solution is increasingly looking like a problem. Governments have steadily jacked up the proportion of course costs borne by students and reduced repayment thresholds even as the amounts of education needed to compete in the labour market have increased.

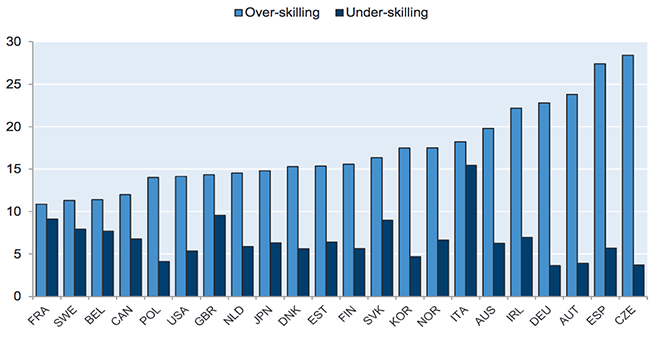

Compounding the problem is the fact that the credentialled are not getting jobs or earning as they used to. Credentialism creates a secular tendency for the numbers of credentials and credentialled to grow more rapidly than the rewards available for distribution, a reality that causes the expectations of the credentialled to fall and those of employers to rise. To take only the case of the best-positioned, the university graduates: in 1977 average graduate starting salaries equalled average (full-time male) earnings. In zigs and zags, that 100 per cent has fallen to three-quarters of average earnings. Over much the same period, the proportion of graduates finding it hard to get a full-time job rose, also in zigs and zags, from one in ten (1979) to almost one in three (2013). Calculating “over-education” is another dark art, but on any calculation it is now so marked and widespread that even that arch-apostle of educational expansion, the OECD, is getting worried.

Components of skill mismatch, selected OECD countries, 2011–12

Notes: Under- (over-) skilled workers refer to the percentage of workers whose scores are higher than that of the min (max) skills required to do the job, defined as the 10th (90th) percentile of the scores of the well-matched workers in each occupation and country. In order to abstract from differences in industrial structures across countries, the one-digit industry level mismatch indicators are aggregated using a common set of weights based on industry employment shares for the United States.

Source: OECD (2015), The Future of Productivity, OECD Publishing, Paris.

One outcome of the pincer movement of rising costs and falling returns is rising student debt. By 2012, total HECS debt had reached $30 billion, of which around $7 billon is unlikely to be repaid. Recent projections suggest that growth in debt may be closer to exponential than to linear. Such problems may be compounded by the relatively recent extension of the HECS approach to VET students.

So far as individuals are concerned, it can be argued that if the return on investment falls too far they can take their investment elsewhere. This ignores the fact that getting a credential is less an “investment” than a life imperative for most young people. It also fails to recognise that while many of those competing in and through educational credentials are “aspirationals” putting in the effort to “better themselves,” many are simply trying to defend whatever relative position they have or avoid unemployment. It’s a matter of sticks as well as carrots, fear as well as hope.

The third and most far-reaching of the drawbacks of credentialism is its role in the near destruction of a work-based learning system. Massive systems of formal education were not constructed on an empty plain. At the opening of the twentieth century most new entrants to most occupations learned on the job. Teachers began their careers as “monitors,” lawyers as articled clerks, accountants as clerks, nurses as juniors, and many engineers in articled pupillage or apprenticeships. Sometimes, work-based learning was linked to further part-time study (as in the case of occupations organised as “trades,” for example), sometimes not. The formal education system was essentially a platform under this larger system of learning, providing the literacy and numeracy necessary to work-based learning.

By the end of the twentieth century most of this system had been subordinated or demolished. The process can be traced in “intergenerational upgrading” (a term that contains an inadvertent value judgement, by the way). As recently as the early 1980s, only a quarter of young accountants had degrees, but that was two-and-a-half times the proportion of their middle-aged colleagues and eight times the proportion of the senior members of the profession. A similar pattern could also be found in pharmacy, architecture, engineering, teaching, physiotherapy, and welfare and social work. Very few, if any, non-graduates are still to be found in any of these groups.

This is not to deny that the established system of learning was in bad shape. It was not delivering the necessary skills and knowledge, and was often both oppressive and exploitative. But as credentialism gathered momentum and formal education interposed itself between the labour market and the labour process, it was conveniently assumed that the work-based system was incapable of reform and must be swept aside, despite evidence to the contrary provided by those few occupations that forced the new system to accommodate the old. As a rough rule of thumb, the more established and secure the occupational group, the more technical and arcane its expertise, and the more closely connected it is to matters of health and safety, the more that group was able to dictate terms to the new credential providers, maintain a respect for craft knowledge, and retain a viable relationship between “practice” and “theory.” Medical practitioners are at one end of that spectrum, teachers very close to the other.

In the less powerful occupations, including nursing and engineering, hostility towards the established system came to border on hatred. The nurses were explicit in their campaign against the trainee system, and did not entertain the possibility that its reform might be better than its replacement. They wanted definition by educational credential for exactly the same reasons that the engineers’ Brian Lloyd wanted it – and he was just as hostile to work-based qualification as the nurses were to hospital-based training.

One of the most influential theorists of credentialism argued that learning could be for its own sake, to get a job, or to do a job. The rise of formal, front-end education at the expense of work-based learning has seen a decisive shift away from the first and third of these in favour of the second, with substantial educational, social and economic consequences.

Learning “for its own sake” has not disappeared but it is certainly at a relative discount. Just one indicator: between 1964 and 1999 in higher education, enrolment shares in arts and humanities (on the one hand) and business studies (on the other) moved in opposite directions. Arts and humanities fell from 36.1 to 24.5 per cent of the total as business studies rose from 11.6 to 26.1 per cent. The old idea of education as an induction into a rich culture and a furnishing of the mind harks back to the days of the cultivated gentleman, but is not altogether wrong for that.

At the same time, learning in order to get a job has gained at the expense of learning to do a job. The constant pressure of credential competition is towards longer courses and higher-status (that is, more abstract and theorised) content. With that has come a cool or lukewarm engagement with study, and an extended period between childhood and fully adult responsibilities and income. More and more young people engage in longer periods of study, the purpose and use of which lie in some uncertain or imagined future. Even content that isn’t padding often feels like it because it comes before it is needed and is therefore not really understood, or is forgotten when the day of its use eventually arrives.

In the conventional economic perspective there is only a problem if the qualification-holder can’t do the job (“under-education”) or has acquired more skills than the job requires (“over-education”). This view is more interested in whether the economy is getting the supply it wants than in the process that does the supplying. Is formal education the only or best or most cost-effective way to develop skills and knowledge? Given that most formal education demands time served as well as learning assessed, and that there is only an approximate relationship between course objectives, course content, what is assessed, and what is required in the workplace, there is a strong prima facie case that extended, formal, front-end education in pursuit of a credential is typically low-productivity education.

There is an irony in these shifts. The more that education has been touted as a response to the demands of the workplace, the more separated from the workplace it has become. It is also ironic that, over the same period, the costs of this preparation have shifted from employers to governments to prospective employees, a tacit acknowledgement that the consumer is the one who really needs all that extra knowledge – not, or not only, to use in the workplace, but to stay in an increasingly intense competition to get into the workplace.

Credentialism constructs the relationship between education and the economy at the wrong point. It shifts the nexus of that relationship from the labour process to the labour market. To draw on some relict terminology, it emphasises the exchange value of education (“learning to get a job”) rather than its use value (“learning to do a job”). Education is often said to be dominated by the economy, and to an important extent it is. But it is also the creature of the economic and other imperatives of individuals, groups and institutions, often at the expense of or without commensurate benefits to the economy as a whole.

THE DIRECTION OF POLICY

There is no point in trying to stop credentialism, and certainly no need to encourage it. The task of policy is to manage it, to use what it makes possible, to do what it doesn’t, and to moderate some of what it does.

Governments should, first, regulate and shape growth in education participation. They should stop talking up numbers, and stop using spurious comparisons with the size of post-school systems in countries that have very different educational, economic and social structures, and which are in (at least some cases) just as mistaken in their policy as we have been. Some kinds of growth should be discouraged, other kinds encouraged.

Governments should, second, discourage front-end education and encourage career and training paths that get as many young people into the workplace as soon as possible and, with that, encourage learning in and by groups as well as by individuals. That approach should certainly include, but should not be confined to, most mid- and lower-tier occupations. Many tertiary education providers are attempting what amounts to a retrofit on the learning–work relationship via internships, work experience placements and other forms of “cooperative education” or “work-integrated learning,” and by developing “profiles” of “the [insert your institution’s name here] graduate.” Peak organisations have developed a “national strategy on work-integrated learning.” (The ultimate academic recognition of a problem came in 2010 with the inception of the Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability.) Some of these developments are a mixed blessing, especially in their use of unpaid labour, and add up to a recognition of a problem rather than a solution to it. A substantial restructuring of the education–work relationship requires, among other things, long-term government commitment.

Third, the priority governments give to research in universities should be transferred to learning and teaching. It’s true that teaching has a higher profile than it did two or three decades ago, but over the same period research has become a mania. Putting an end to the subsidisation of research by teaching would be one step in the right direction. Another would be a rewards system that makes good teaching and learning as lucrative as research. And another: a sustained assault on the legitimacy and consequences of research-obsessed international league tables – perhaps by developing an alternative to them.

Fourth, learning should be redistributed, with the core focus being on the gaps between the best and the worst, and the shortest and the longest educational experiences, rather than on social group distribution. The way to kill two birds with one stone is to concentrate on the former. That would require, among other things, giving the VET sector (including school-based VET programs) the policy and funding focus currently given to higher education, and extending “education” policy into Scandinavian-style or “active” labour market programs.

Fifth, policy should tackle the conflict of interest that permits the same institution to provide, assess and credential. It should confront the fact that occupational groups involved in this arrangement seek rents as well as standards. People learn in all sorts of ways and places, the more so in a digital world, in a highly mobile labour force, and in a constantly changing labour market. Much of this learning goes unrecognised and/or unused because it was acquired outside the formal education-recognition system.

In that loss, education providers play an important part. Rather than take advantage of major advances in the articulation of occupational and other standards and in the assessment of performance and capacity, they have continued to use their power over credentials to demand time served as well as attainment assessed (and often use the former to compensate for the quality of the latter). The “recognition of prior learning” has been confined largely to the VET sector, where it has sometimes been abused by private-sector bucket shops.

Some tertiary providers have an inkling that the game might be changing. Big employers are not as shy as universities about using advanced forms of performance and capacity assessment in addition to, or even instead of, educational credentials. Digitally mediated forms of assessment and “micro-credentialling” promise a direct relationship between capabilities needed and capabilities acquired, irrespective of where or how or when they were acquired. These developments will have their effect over time, but they will battle against the entrenched power of the education sector (its universities in particular) and occupational groups. It is in the interests of government, including its budgetary interest, to weaken the nexus between formal provision and credentialling.

A sixth suggestion: policy should pay as much attention to the use of educated labour as it presently does to its production. There are few settled questions in the economics of education, but one that is close to being agreed is the view that the productivity of individuals is highly dependent on the circumstances in which they work, and the extent to which those circumstances make the most of what individuals bring to the task.

A view of the past half century that takes account of the workings of credentialism suggests that governments have exacerbated its effects rather than managed them. They have fuelled expansion of the system rather than focused on its shape and disposition, encouraged more and longer front-end education rather than work–study combinations and work-based learning, given priority to research and to the top half of the system rather than to teaching and to the bottom half, taken for granted the right of education providers and occupational groups to set the terms on which knowledge and skills will be made negotiable in the labour market, and concentrated on the provision of skills and knowledge rather than their use. The sole substantial exception to most of these rules was John Dawkins’s bold but ill-starred “skills agenda,” quickly overwhelmed by his even bolder expansion of higher education, as prompted by the OECD. To the extent that bad policy comes from bad ideas, human capital theory has a lot to answer for.

THE BASIS OF POLICY

What turned Martin into an apostle of human capital theory was a graph supplied by the OECD, and a table provided by the economists on whom the OECD relied. The graph showed two diagonal lines running from bottom left to top right, along which were scattered the names of twenty or so countries. Up in the top right-hand corner were the richest and most educated (the United States and Canada). At bottom left were the poorest and worst-educated (Portugal and Turkey). The table showed much the same thing happening to individuals. The more education Americans (men, that is) had obtained, the higher their incomes. Those with no education got 50 per cent of the amount earned by those with eight years of schooling; four-year graduates got 235 per cent.

The conclusion drawn was that this was “human capital” at work. Both individuals and economies were more productive when they had more human capital to call upon, and education provided it. Both would be wise to invest, because education offered an excellent rate of return.

The idea has intuitive appeal, but it ran into immediate and vigorous opposition, on three grounds particularly. Which of education and the economy was the chicken, and which the egg? And: do individuals get paid more because their education has made them more productive, or because it has given them qualifications that get them into the more productive jobs? And, third, even if education makes individuals more productive, is that in its turn making the economy as a whole more productive?

Economists pride themselves on empirics, but empirics were hard to come by – so hard that by 1975 the leading British educational economist of the day, Mark Blaug, summarised the many strikes against human capital theory and concluded that its “persistent resort to ad hoc auxiliary assumptions to account for every perverse result” and the resulting tendency to “mindlessly grind out the same calculation with a new set of data” were signs of “a degenerate scientific research program.” It has been dogged ever since by the difficulty in finding correlations as sweet as those that seduced Martin.

Many academic economists left the big claims about education driving economic growth to one side and got on with the more useful task of investigating when, how and why skills and knowledge are or are not used to advantage. The OECD has done much to support that work, but it also had other fish to fry. It set out to annex education to the economy (it is, after all, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), and it needed the big picture to do it. In a tireless campaign to keep the argument afloat, it engaged in one “rethinking” after another, introducing modifications, nuances and qualifications, gradually shifting the emphasis from explanation to the safer ground of prescription, but never abandoning the basic idea that education drives economic growth, and more education means more growth. And that is what governments have seized upon.

It can be argued that from the introduction of HECS in the 1980s through to Bradley’s “demand-driven system” it has been market economics rather than human capital theory that has given the expansion objective its golden run. But market economics has served mainly to clear obstacles on a course long since charted by human capital theory. It can also be argued that it’s not human capital theory that is at fault but the policy-makers. In an address to a high-end audience at a Committee for Economic Development of Australia forum, two senior policy-makers and advisers quoted with approval the conclusions of a British researcher who argued that governments have driven expansion of education on the basis of a “simple reading of human capital theory” and the misplaced assumption that it is “a sufficient basis for analysis and action.” The implication: if governments and their policy-makers read more widely and carefully, they would pay more attention to the character, quality and distribution of education.

That is certainly so, but the trouble is that it’s not just governments and politicians who use human capital theory. It is also the huge and hugely influential education industry, in which even thoughtful and critical members use “a simple reading of human capital theory” almost as a reflex. Others, including Deloitte and Universities Australia, offer it as gospel, conflating individual with economy-wide benefits; asserting that graduates are more productive and that it is formal education that makes them so; arguing that advantages enjoyed by graduates “on a range of social indicators” come from being university-educated rather than from the position in the social pecking order to which a degree gives access; failing to note that benefits to one individual may be costs to another; claiming that better economies come from bigger education systems; and resorting to weasel words (“is associated with,” “it is well established,” “it is widely accepted,” and so on) to slide past awkward questions about chickens and eggs, causation and correlation, and the gap between claim and evidence. Notably absent from Deloitte’s analysis is that core economic concept, “opportunity cost,” and the consideration it might provoke as to alternative ways of spending what is spent on universities, and more cost-effective ways of doing what universities do.

The human capital idea lends itself to this sort of special pleading. What confuses both thought and policy is the fundamental conception, the underlying imagery. Human capital theory takes just one part of the education–society relationship – what formal education does or can do for the economy – and declares it to be the main game, or even the only game. It was founded on the notion that building a healthy economy is mainly a matter of loading up individuals with portable “skills,” and has great difficulty in absorbing the fact that ways of doing things in workplaces and economies (and societies) are as much, or more, the property of groups as of individuals.

But the theory’s most damaging ingredient, responsible for encouraging governments in their myopic focus on “increasing educational attainment,” is built into the very term “human capital”: the assumption that it’s all about accumulation, right down to preposterous calculations of the total value of the “stock of human capital” and of what an increase in the Year 12 retention rate will do to GDP, another case of economic modelling gone mad. It has saturated and twisted the language so that the effects of education become “benefits,” expenditure is transformed into “investment,” and analysts of “skills shortages” forget that much of what they are talking about is the supply of holders of occupationally constructed, regulation-backed credentials, aka union tickets.

In the argument presented here, the most consequential weakness of the human capital argument is its incomprehension of the nature and effects of credentialism. A good functionalist social science, all it can see are functions performed (so long as they are performed on behalf of the economy), and malfunctions such as “over-education,” which it calls “credentialism,” a confusion of an effect with the dynamic that generated it. It would be going too far to say that the human capital idea is simply a part of credentialism, but it has served both to obscure and to advance credentialism. Economics understands some important things, but in its arrogance as “the mother tongue of policy” it does not understand that there are equally important things that it does not understand. With rare exceptions, even its discussions of “credentialism” make no reference to – much less try to comprehend – key texts in the history and theory of credentialism. And with equally rare exceptions, the economics of education knows a lot more about economics than education.

The formal education and training system is neither powerhouse nor gravy train. It is, among other things, both. Neither is an incidental by-product of the other. Both impulses powerfully influence the size, disposition, culture and effects of formal education and training. By taking the economists’ radically incomplete view of the matter, policy has had the paradoxical effect of exacerbating the impact of credentialism at the expense of the education’s economic and other contributions. Hence a seventh and final piece of advice to government: do, as advised, listen more carefully to what the economists have to say, then seek other counsel. •

Any thoughts? Comment via Disqus below...

This is a substantially revised, expanded and updated version of an article with the same title published in the Bulletin of the National Clearinghouse for Youth Studies, 7:2, May 1988. It has benefited from comments and suggestions by Mark Burford, Gerald Burke, Sandra Milligan and Richard Sweet. Needless to say, they bear no responsibility for the result.

In addition to the linked sources, the article also draws on:

• “Goodbye, Florence: The Nurses’ Struggle for Status Has Ended the Age of Florence Nightingale,” by Elizabeth Pittman, in Australian Society, February 1985.

• “Work-based Learning in Australia’s Initial Vocational Education and Training System,” by Richard Sweet, in the forthcoming European Training Foundation book, Work-Based Learning: An Option or Essential for VET?, ETF, Turin, 2016.