WALKING into the booklined room, the noise hits you like a wave. The raised voices of patrons, the clatter of chairs, the shuffle of bags and laptops. Staff are on patrol but seem oblivious to the chatter and ceaseless movement.

It’s a fair bet that State Library of Victoria managers would be disappointed if it was quiet in here. I’m sitting in Mr Tulk, the library’s vibrant, street-level cafe, which is audaciously named after the Melbourne Public Library’s severe and bookish first librarian. Books that might have once served the library’s primary aims are stacked horizontally up the walls, contributing to an ambience that is clearly popular in Melbourne’s competitive cafe economy.

As you walk further into the building, though, there seems little to distinguish the activities in Mr Tulk from those in the library’s reading rooms. People are tapping away at laptops, reading books, sending texts, talking – everything but drinking coffee.

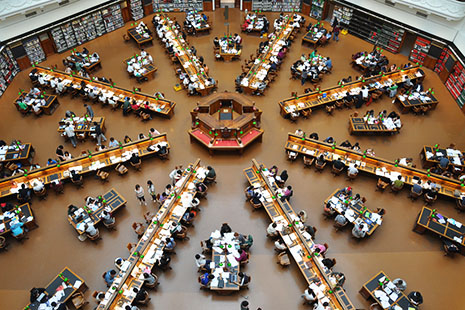

At least this is the view of several correspondents to Melbourne’s Age newspaper over the past week. Melbourne academic and writer Leslie Cannold fired the first salvo, suggesting that the library’s magnificent domed reading room was too noisy for concentrated work. The room is a stop-off for school tours of the building, but it is the after-school atmosphere that particularly annoys Cannold. The lack of self-regulation by library patrons is compounded by the invisibility of staff. The reading room’s central raised desk, from where library staff once observed all corners of the room, is no longer used. The sign indicating that this is a place reserved for silent work and study is, on Cannold’s account, a case of false advertising.

The library’s CEO, Anne-Marie Schwirtlich, sprang to the institution’s defence by pointing out its success in boosting visitor numbers among young people. The paradox is that, despite complaints about noisy teenagers, this cohort is notoriously difficult to attract to public cultural institutions. Museums and libraries have devoted considerable resources to developing imaginative and engaging programs for teens and young adults, especially young males. Equity and access concerns, and the self-interest involved in building future audiences, lie behind this strategy. Critics accuse cultural managers of sacrificing their core audience in the chase for younger patrons, but research has demonstrated that early exposure to libraries is important in establishing a pattern of life-long use.

In one sense, librarians are trapped by their own noisy rhetoric. Libraries Are Loud (But Who’s Listening?) was the title of the inaugural conference of Public Libraries Australia, the peak body formed in 2005 as a focal point for sectoral advocacy. The motif resounds across the library world. Libraries Out Loud was a conference theme in 2010, this time hosted by the Illinois Library Association. Get it Loud in Libraries is a banner for a series of music concerts in British libraries, developed following a 2005 government report arguing that the 14–25 year old age group “don’t ordinarily use libraries, but love modern rock and pop music.” Simple – combine the two! Libraries Are Loud, a series of music performances by young people in New South Wales regional libraries, echoes the British program.

The rhetoric of loud libraries is the most in-your-face instance of a wider conversation about libraries and change initiated by librarians around the world. One part of this conversation circulates around the major impact of digital technologies and online information on library services and institutional forms. Another part focuses on the role and demeanour of librarians, and their interaction with library users. Sue McKenzie, head of Brent library service in north-west London, recently summarised the case for change thus: “people are fed up with what they say is an outdated image of libraries – humourless places staffed by strict officials demanding silence in the aisles.” But when the web managers of the Brent community information website, BRAIN, conducted a poll on the subject, 81 per cent of respondents “said NO to noisy libraries.”

Public libraries have never served a single public with a broadly shared outlook and code of behaviour. Major libraries, in particular, have a range of audience segments to cater for. The State Library of Victoria, for instance, has long had specialised reading rooms and collections, and has pitched to people with specialised information needs such as technical and business information. Now the activities of major libraries typically encompass online and in-person information services, seminars, exhibitions and other public programs, and a range of ancillary commercial activities. Changing information media and learning styles, too, influence the comportment of library users. The rearrangement of public reading rooms around group learning and wi-fi access is a signature of major city library regeneration, as visitors to the Victoria’s State Library and its newly renovated Queensland counterpart can observe.

But dynamic institutional developments like these won’t necessarily reassure the people who worry that libraries are becoming too noisy to perform their central function. Have we come to the end of the short historical moment in which silent reading took hold?

As the cultural studies scholar Ian Hunter reminds us, silent reading is a relatively recent development in the history of literacy. Emerging with the rise of Protestantism in Europe, the practice of intense, inward meditation on written texts was both a critique of rote learning and a strategy to promote self-regulation and personal development. The educational apparatus that developed with the rise of modern industrial states followed this pedagogical strategy. Museums and libraries paid particular attention to the civic ethos of their visitors – that is, to establishing and reinforcing behaviours appropriate to the public and institutional contexts. In the nineteenth century concern focused more on the newly literate working class than young people. The Melbourne Public Library installed a washbasin in its foyer for patrons prior to accessing the bookstock. The motif of cleanliness and personal uplift was extended to the collection, with Augustus Tulk and the library’s first chairman, Sir Redmond Barry, initially refusing to acquire current works of fiction.

Nor is noise in libraries uniformly registered. For example, the London Times columnist Sathnam Sanghera complained in 2009 that the British Library reading room was too quiet. In such an ambience, he suggested, sounds amplify, increasing the likelihood of distraction. For Sanghera, self-regarding behaviour rather than noise per se is the larger problem confronting public libraries. He, too, has a problem with young people invading the library cloisters, giggling and whispering, turning the place, in his salacious description, into “a petri dish of simmering lust.” No wonder he has trouble working there.

Rather than conduct a debate over decibel levels, behaviour in public libraries might better be analysed in terms of civility and public spiritedness. The political theorist Michael Walzer has long been concerned with what he sees as a decline of civility in liberal democracies. Walzer argues that cooperation and self-restraint are important practices of citizenship. The connections with silent reading are clear. But Walzer argues that civility should be based on active commitment to the public sphere rather than deference to authority. In Victoria, messages of civility and respect have a new political import with the development of a whole-of-government “respect agenda” to be overseen by the planning minister, Justin Madden. But a media strategy leaked from Madden’s office describing potential manipulation of the community consultation over the redevelopment of Melbourne’s landmark Windsor Hotel suggests the message has a way to go within government too.

Regulating behaviours and coordinating potentially conflicting activities is no doubt difficult in large and complex institutions. It is equally difficult in smaller municipal or regional libraries, many of which have less space to segregate programs. During the post-war phase of suburban growth, when much of Australia’s municipal infrastructure stock was built, separate “youth” facilities were common. Rationales included a desire to minimise program conflicts and provide young people with a chance to self-manage. Civic regeneration in recent years has reversed this trend, focusing on integration and multi-use facilities. Libraries are at the centre of this strategy. Additionally, Commonwealth and state school building programs increasingly favour shared school-community libraries. Such initiatives suggest that the question of conduct in public libraries, and in the wider public sphere, will require much wider discussion.

The State Library of Victoria’s domed reading room has been graced by some of Australia’s finest writers – and deserted by them, according to Cannold. Finding quiet or silent spaces is increasingly difficult in urban settings. In the 1980s the educator Ivan Illich proposed that silence be thought of as a commons – a resource that everyone shares and everyone has a responsibility to nurture. The library’s magnificent Swanston Street building is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register. The entry describes in detail the building’s evolution and architectural features, culminating with the construction of the reading room in 1913, rightly observing that the library is both an essential part of Melbourne’s culture and a site of national significance. But a quiet ambience is also part of the institutional heritage of major libraries, and just as palpable as the building fabric. Perhaps it is time to revise the building’s heritage listing to include its atmosphere, and give the silence of the reading room some statutory protection. •