Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage

By Barbara Santich | Wakefield Press | $49.95

BARBARA Santich’s Bold Palates is an annotated album of the Australian family at meal time, documenting everything from jugged hare, lamingtons and meat pies (and tomato sauce) to the barbie and the picnic. As one of the senior members of the family, I found some of this half-familiar, and much of it new and fascinating. I’d recommend particularly the biographies of the pumpkin – stretching all the way from the First Fleet to Flo’s notorious scones – and the descent of “spag bol” from moderately haute cuisine in the 1930s to the ignominy of a can.

Santich records many efforts since the mid-nineteenth century to define the National Dish, and how the candidates for that honour have changed with the times. Our real gastronomic distinctiveness, she concludes, lies not in pavlova, Vegemite, lamb chops, Anzac biscuits or any other dish or dishes but in our “enthusiasm for new foods, our readiness to adapt, improvise and reinvent.” She insists that we’ve never had a single cuisine, much less a monotonously British one as is so often assumed, and we certainly didn’t wait for the postwar immigrants to bring variety of food type, origin and flavour into our diet.

I know from my own experience that this is true, up to a point. I was the beneficiary of a cuisine my mother got from her mother and grandmother, extending well back into the nineteenth century. It was rich in offal (including liver, brains, tongue, tripe and kidneys), pungent sauces, pickles, relishes and chutneys, a cheddar so magnificently matured that it could compete on equal terms with heavily spiced pickled onions, jams and beautifully preserved fruits, and an array of sweets, cakes and biscuits that even Brunetti’s would struggle to match.

And then there was bush tucker, both native and introduced. My father and his brothers and cousins learned as boys to trap yabbies and crayfish, shoot rabbit, hare, scrub turkey and duck, and fish for river callop and Murray cod as well as whiting, bream, tommy ruff, snapper and many other fish of the ocean. Earlier generations ranged even more widely, Santich points out, because they could and because they had to. Pigeon, flying fox, bandicoot, echidna, wombat and many others fell in the cause of (often unsuccessful) culinary experiment.

Although Santich marshals some intriguing menus, advertisements, lists of imported goods and the like, these don’t suggest the degree of cosmopolitanism and feverish innovation now so widely enjoyed. I went to university at about the time this revolution was getting under way, and soon became conscious that in leaving home I was also leaving one gastronomic universe for another. My hunch is that if we have always had bold palates, they’re a lot bolder now than ever before.

It would have been interesting to have all this set in a context of the subsequent fast- and prepared-food revolution – or counter-revolution? – noted rather than integrated into Santich’s overall picture. I wonder, too, how far “enthusiasm for new foods, our readiness to adapt, improvise and reinvent” marks off Australia’s gastronomic heritage from that of other so-called settler societies, particularly the United States.

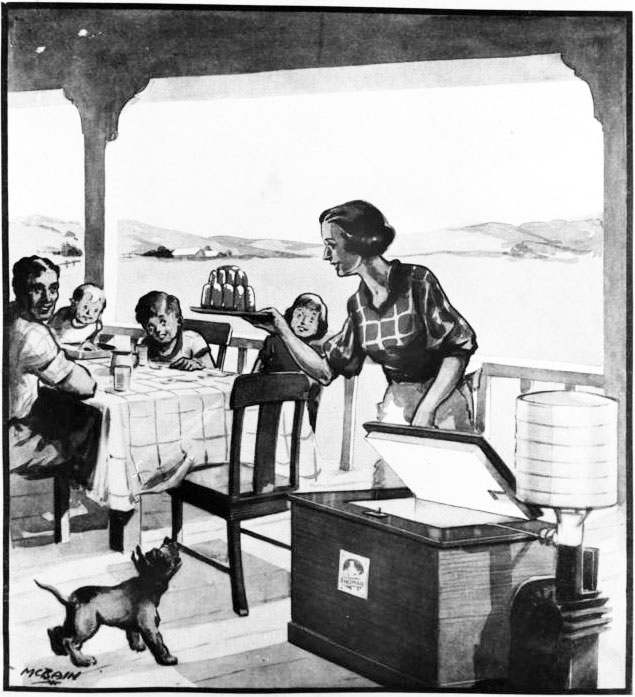

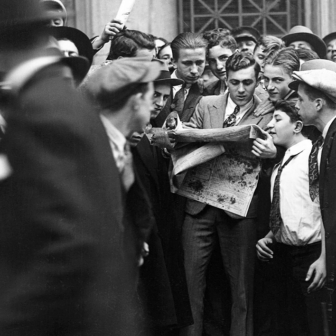

The story of Bold Palates is told as much through reproductions of photographs, paintings, letters, diaries, advertisements and the like as through the text itself. There is much enjoyment to be had in browsing though this wealth of material, even if it is displayed in a rather self-consciously retro layout. But the profusion of illustration also gets in the way of a good read, as does the organisation of the book around themes and topics – “bush tucker,” “land of picnics,” “chops rampant,” “land of cakes” and so on. Each of these contains a narrative, but they combine to form a collection more than an integrated history. Santich’s muse is food rather than history. •