In Praise of Idleness

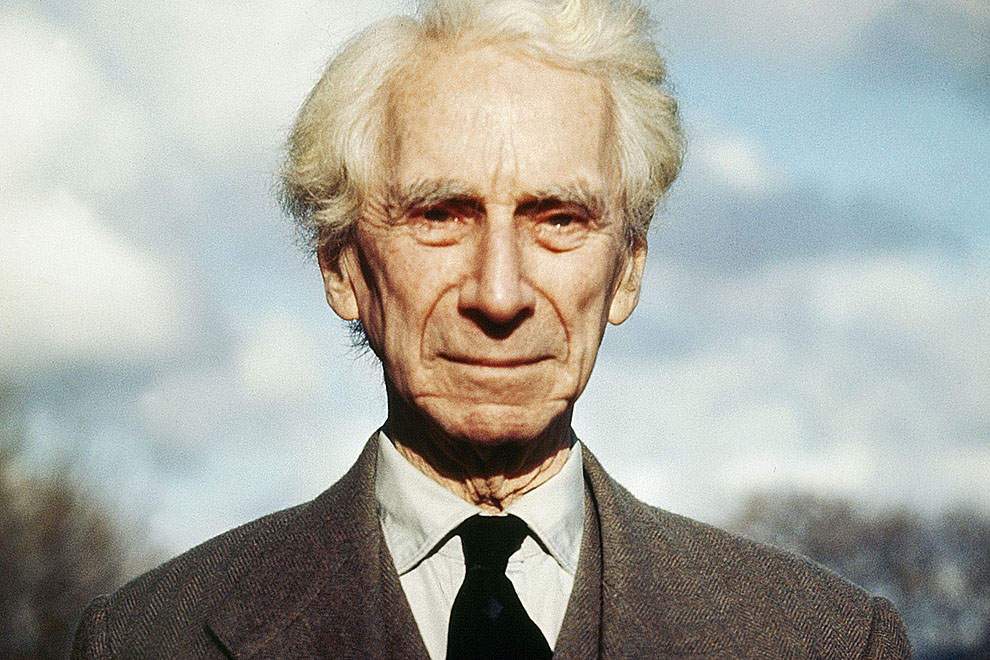

By Bertrand Russell and Bradley Trevor Greive | Nero | $19.99

Technologists say that we are on the brink of an industrial revolution that will replace human labour with artificial intelligence. Most jobs, they say – even work that requires special skills – will be done by machines. But while the utopian literature of past centuries looked forward to lives free of labour, we are more inclined to greet the prospect with dismay.

Some of our dismay comes from a fear that many people will end up poor and unemployable, and only a few of us will benefit from new opportunities. But our trepidation also reflects the role that work plays in our lives. For most people, having a job is a source of self-respect.

The social changes we face require a rethinking of our values. It is this task that the philosopher Bertrand Russell undertook eighty-four years ago, at the height of the Great Depression. His essay, In Praise of Idleness, has been republished with extensive notes, an afterword and a foreword by Bradley Trevor Greive, an author of popular humorous books. As Russell’s witty companion, Greive informs and entertains us with interesting facts about Russell’s life, works and influence. Russell’s writings are a great discovery that he wants to share with his readers. “Russell’s every neural impulse,” he writes, “was an earthquake that rattled my tiny brain around inside my head like an oyster in a tumble dryer.”

Russell was born in the age of Queen Victoria and was active into the 1960s. Among philosophers, he is most noted for his work on the foundation of mathematics and his explanation of why the sentence “the present king of France is bald” makes sense even though there is no such person. As a public intellectual he was notorious for his criticism of religion, his pacifism, and his advocacy of sex education and gender equality. He was once turned down for a position at the City University of New York out of a fear that he might corrupt the morals of the young.

Russell wrote seventy books and thousands of articles, and gave countless lectures and interviews. He went to prison for his opposition to the first world war and, with Jean-Paul Sartre, organised an unofficial war crimes tribunal to draw attention to the misdeeds of the Americans and their allies in the Vietnam war.

Russell not only wrote a lot, he also wrote well. When my students ask me to recommend a book on the history of philosophy I always suggest they read his History of Western Philosophy. Though full of his philosophical prejudices, it is far more interesting and readable than texts that try to be more scholarly and even-handed.

Greive is impressed not only by Russell’s output but also with his refusal to endorse common opinions without subjecting them to criticism and his willingness to accept criticisms of his own views. “Ultimately what made Russell a more gifted thinker than most – and by most I mean virtually everybody who has ever lived – is that he was happy to be unsure or indeed proved wrong.”

But it is not just Russell’s ability to doubt that Greive wants to feature; it is also his wisdom. The text of In Praise of Idleness is broken up with quotes from other of Russell’s writings, each accompanied by Greive’s remarkable illustrations: big-eyed, expressive adaptations of exotic animals originally drawn by seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century illustrators. “When a man tells you that he knows the exact truth about anything, you are safe in inferring that he is an inexact man,” says Russell, and this quotation is accompanied by a puzzle-eyed monkey and a frog searching for something that has eluded its grasp – perhaps the exact truth.

Should we accept Greive’s assessment of Russell’s greatness? Philosophers are divided in their opinion about the worth of Russell’s philosophical works – as they are divided about everything else. Many of the views expressed in his more popular books are now widely accepted as having been superseded. Despite the clever aphorisms that Greive extracts, some of his writing has not aged well. But Greive does us a service by bringing In Praise of Idleness to our attention. Its republication is a timely resurrection of a work on a subject that we need to think about.

Russell’s basic argument is easy to state. The belief that all the work we do is virtuous or necessary is an illusion. Modern technology could allow everyone to enjoy an adequate standard of living while doing a lot less work – about half, in fact. All the work needed from each individual, Russell thinks, is four hours a day. Freed from spending so much of our lives at work, we would have the leisure to engage in enjoyable and creative activities to the benefit of ourselves and society.

“In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day,” Russell writes,

every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving… Men who, in their professional work, have become interested in some phase of economics or government, will be able to develop their ideas without the academic detachment that makes the work of university economists often seem lacking in reality… Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out.

Russell’s argument seems easy to criticise. An economist is likely to tell us that arranging the economy so that everyone has an adequate standard of living and just four hours of work would require too much interference by government. A sociologist will add that most people won’t want to work less if this means that they can afford fewer consumer goods. A psychologist is likely to doubt whether people would really benefit from having more leisure, and an international relations expert will certainly be scornful about Russell’s idea of how war can be stopped.

But these criticisms are based on existing ways of living and valuing. Russell is asking, and trying to answer, basic questions about the value of work and leisure, the way we ought to live our lives, and how we can be happy and productive. He is trying to persuade us to change our way of thinking. The issues he is tackling are important for us, and his conclusions require serious examination, even if we end up disagreeing with them.

Work is what keeps an economy going and gives people a means of life, so to question its value might seem like a ridiculous and fruitless exercise. For most people, though, work means being forced to spend a large part of their life doing what they don’t really want to do. In his provocative way, Russell compares work to slavery, and sees the fight for the eight-hour day as one of the most significant struggles of the labour movement. He is simply proposing a more radical version of what these struggles aimed to achieve.

In saying that work in a modern economy is a form of slavery, Russell is operating with a narrow conception of what counts as work. Work is of two kinds, he says: “first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so.” Manual labour is what he has in mind, not work in the service industries that play such a dominant role in developed economies. He is not thinking of childcare, nursing, social work or any other kind of work where the prominent activity is relating to other people. And he does not seem to be speaking for those who like their work and think it is worthwhile, or those who get a kick out of workplace competition and a sense of accomplishment from a job well done.

Russell believes that there are also other reasons why we should be critical of work as we know it. He thinks that we have imbibed a morality that has made willingness to work into a virtue. We admire those who work hard, put in the hours and take on extra responsibilities, and we denigrate those who are seen as slackers. Russell calls this a slave morality. He also thinks that work breeds conformity and prevents people from thinking critically about what they are doing. The investment banker who gets a thrill from buying and selling bonds is as much in thrall to the requirements of the job as the labourer on an assembly line, and is as little inclined to reflect on the ethics of what he or she is doing.

The worst thing about work, according to Russell, is that it blocks creativity. It leaves us at the end of the day without the time or inclination to reflect on what we are doing or to engage in any activity that requires a creative use of our mental faculties.

Idleness is praiseworthy, Russell thinks, because it frees us up for creative and enjoyable activities. The plausibility of this statement depends on understanding what he means by idleness. He makes it clear that what he praises is not the forced idleness of the unemployed or the idleness of the free rider who expects to live off the labour of others. Idleness is not spending your time in passive activities or filling your days with Facebook. It is the space you can make for yourself, free from the demands of your working life, to observe, reflect, play, engage in hobbies, lose yourself in your imagination or learn new things.

Greive thinks that Russell’s ideas about the value of idleness were influenced by his childhood experiences. Brought up by a domineering and demanding grandmother, Russell would escape from his lessons and lose himself on the family estate, observing nature and reflecting on what he was learning. He later regarded this time out from the demands of his formal education as the most important part of his childhood.

It is certainly true that Russell has a typical philosopher’s idea of what is good for a person: namely solitary meditation. Most people would probably prefer to spend their leisure time socialising or participating in family life. But these activities can also be both enjoyable and productive. We don’t have to share Russell’s preferences in order to appreciate what he says about the value of idleness.

How about those who wouldn’t know what to do with more free time? Russell thinks that more education would solve that problem – presumably an education that emphasises creativity and critical thought rather than one that concentrates on preparing people for a life of work.

Idleness, Russell argues, is good for individuals, and it is also good for society. It stimulates creativity and it makes people more kindly and less inclined to fight each other. Greive enthusiastically agrees, at least about the former. “Russell’s argument is a call to action for every citizen of our age of ideas and, if applied, heralds the next wave of enlightened entrepreneurs.” Whether idleness is the mother of invention, whether people with more free time become kinder – these are propositions for which we need more evidence. But even if idleness is not the key to peace and human progress, its value for individuals is a sufficient reason to recommend it.

You can be impressed by Russell’s praise of idleness and remain doubtful about the practicality of his ideas. Greive, the author of books about personal life, takes Russell’s essay as a call for individuals to change their priorities. He tells us that he was inspired by Russell to make better use of his spare time. “Over the next ten years I travelled the world, founded a national poetry prize, participated in wildlife conservation programs on every continent, qualified to be a Russian cosmonaut in Moscow, competed in Polynesian strongman contests in Moorea and took up cooking, gardening and adventure sports.”

Russell is not just advocating a change of values, though. He also wants a revolution in social and economic life. We should stop producing so much – a heretical idea for economists – and be satisfied with less. We should aim for a society where everyone contributes more or less equally to the labour necessary to ensure a decent life for all. Presumably this requires not only a fair amount of material equality but also quite a lot of social engineering. It is not obvious that there is scope in this social world for capitalists to set the terms of employment and maximise output in order to produce a profit, or for entrepreneurs to get rich.

What Russell is advocating (contrary to Greive’s view) is a form of socialism. Although he disliked the dictatorial power of Soviet rulers and their devotion to making people work, he didn’t object to the idea of a centrally planned economy. Russell’s ideas, in fact, can be located in a tradition of socialist thought about how work can become less onerous and more self-fulfilling in a society not constrained by the requirements of capitalism. For those suffering from the Great Depression, the view that capitalism had to be replaced by a managed economy was almost common sense – which is how Russell treats it.

The fall of the Soviet Union is supposed to have taught us that a planned economy doesn’t work. Does this mean that Russell’s proposals for changing our economic and social life belong in the dustbin of history? Perhaps we should instead take to heart Russell’s insistence that received truths ought to be doubted. A planned economy in an age of artificial intelligence may be a feasible proposition, and it doesn’t have to be undemocratic. But even if we reject Russell’s socialism we need to take up the discourse that Russell hoped to initiate about work and leisure and how they should be distributed. A good life for everyone in the twenty-first century depends on it. •