As the Victorian Liberals begin the dispiriting task of working out why they lost last month’s winnable election campaign, they could do worse than to ferret out a copy of Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals.

Alinsky, a radical activist who emerged from 1930s Chicago, has been largely forgotten in Australia, especially perhaps within the Coalition, which he would undoubtedly have numbered among the “enemy.”

But Rules for Radicals, written just before Alinsky’s death in 1972, stands as the foundation text of what has become known as “community organising” – building the capacity of marginalised communities to take collective action to improve their living conditions. Unexpectedly, Alinsky has also become a guiding influence in electoral campaign management, as political parties and candidates adapt the principles of community organising to the electoral contest.

For this reason it is possible to trace a direct line of descent from Alinsky, via community organising, to US president Barack Obama, and from there to the electoral success of the newly minted Victorian premier, Daniel Andrews.

Consider the modest flat in the back streets of the Melbourne sandbelt suburb of Seaford, hired by the Labor Party as the war room for its campaign to win the marginal Liberal-held seat of Carrum. The living room was converted into a phone bank, equipped with computer screens linked to the Labor Party’s database of undecided voters, and staffed for weeks by hundreds of volunteers.

With due allowances for the new technology and the Australian electoral context, the scenes inside that rented flat exhibit the hallmarks of classic Alinsky-style community organising: its formalised top-down structure of community organisers, its emphasis on recruiting and training volunteers, and its strategy of mobilisation through storytelling and conversation.

Labor leader Daniel Andrews talks to members of Labor’s Community Action Network in Geelong.

Similar scenes were repeated in twenty-five other marginal seats selected by the Labor Party. Labor won twenty of them, including Carrum. It is understandably eager to take credit for this latest success of its micro-targeting campaign strategy – and to put the frighteners up the Coalition. Media reporting since the campaign has reflected this agenda.

But beyond the partisan struggle, there is a bigger story emerging here. Political parties are supposed to be dying, or surviving as hollowed-out shells. Members have been leaving in droves; branches are closing; partisan attachments are withering; political efficacy – the sense that “I can make a difference” – is declining around the world, and the whole electoral contest is seen as an increasingly irrelevant exercise in spin and manipulation. Academic research, media commentary and internal reviews within the parties themselves all support this dominant view.

But if parties are dying, no one told the 5000+ Labor volunteers slaving away in the flat in Carrum and in the other marginals. If this is the age of disillusion, how did Labor persuade its volunteers to make half a million phone calls and knock on more than 170,000 doors in the course of an eight-week campaign? Presumably, these volunteers thought they were making a difference. So is there a pulse still in the political parties?

Saul Alinsky’s aspirations for community organising were summed up in his assertion that while Machiavelli had written The Prince “for the Haves, on how to hold on to power,” he had written Rules for Radicals “for the Have-nots, on how to take it away.”

The book reflects his lifetime developing, practising and teaching community organising – from the working-class “Back of the Yards” district of his native Chicago in the late 1930s, through African-American communities in the northeast and Mexican-American farm workers in California, into the 1970s. The Industrial Areas Foundation he created in 1940 continues as the largest and oldest US network of church and community groups devoted to leadership development and citizen-led action. Alinsky’s work was less about the big social movements of the times – civil rights, the Vietnam protests, feminism – than about the local level: how can people living together in marginalised communities be mobilised to improve their living conditions?

To answer that question, his starting point was the insight, quintessentially American, that each individual has his or her own self-interests. People can be mobilised to act if they recognise they are acting in their own self-interest. But this doesn’t happen spontaneously; it needs to be organised.

Alinsky’s method therefore placed a heavy burden on the community organiser, who had to get into the community, listen and learn about all these individual preferences, and develop a strategy to aggregate them into non-violent collective action that will achieve change.

For Alinsky, then, it was all about identifying and training the right individuals who could do the organising. They needed to be strategists. So his book sets out twelve “rules” for effective action. Alinsky asserts these rules with authority and craftiness, like an American version of the military sage Sun Tzu (author of Art of War). “Power,” he states in the first rule “is not only what you have but what the enemy thinks you have.” Lacking money, the Have-nots have to build their power from their own flesh and blood. The second and third rules: “Never go outside the expertise of your people” and “Whenever possible, go outside the expertise of the enemy.” In other words, don’t cause fear and confusion in your own ranks; cause them in your opponent’s. This is pragmatism, not dogmatism; he subtitled his book: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals.

Twelve years after Alinsky died, a young African-American college graduate named Barack Obama arrived in Chicago to start work as a community organiser. Obama spent three years with the Developing Communities Project, a coalition of churches and union groups seeking to revive manufacturing jobs on Chicago’s South Side. He also worked briefly as a trainer for the Gamaliel Foundation, an Alinsky-inspired group named after the rabbinical scholar who taught St Paul. Without mentioning Alinsky, Obama recalls in his autobiography, Dreams From My Father that he was directed to interview people to “find out their self-interest”:

Once I found an issue enough people cared about, I could take them into action. With enough actions, I could start to build power. Issues, action, power, self-interest. I liked these concepts.

Twenty years later, organising his presidential campaign, Obama adapted some of the key organising principles and practices of community organising. His campaign was built on a tight hierarchy of field staff: paid “organisers” at the state and county level, who recruited volunteers as “precinct captains,” who in turn recruited other volunteers, by the hundred, who were grouped and trained in functional tasks such as doorknocking, phone calling and events. These volunteers were treated as valued contributors, not drones, and provided with extensive training; the staff philosophy, as recorded by campaign manager David Plouffe, was “Respect. Empower. Include.”

Importantly, the volunteers were mobilised less by any appeal to hard and fast policies than by the appeal of Obama’s values – hope for change, trust, aspiration for social equality and opportunity – and his storytelling about his “improbable journey” to prominence.

One of the architects of this campaign structure was another community organiser, Marshall Ganz, who in 1964 had abandoned his Harvard undergraduate degree to join the civil rights movement in Mississippi. Ganz had then worked for sixteen years alongside Cesar Chavez with the Mexican-American farm workers in California, only returning to Harvard in 1991 to complete his undergraduate degree. His doctorate thesis about community organising became a prize-winning book, Why David Sometimes Wins. Ganz is now a Harvard professor whose course, Leadership, Organizing and Action, attracts activists from around the world.

Among the thousands of volunteers working within Obama’s 2008 campaign structure was a small group of Australians who had travelled to the United States to get involved, and who were inspired and energised by what they found. One of these self-titled “Aussies for Obama,” Stephen Donnelly, returned four years later, after Obama’s re-election in 2012, to meet with Obama campaigners about best practices in electoral organisation.

Stephen Donnelly is now the Labor Party’s assistant secretary in Victoria and organised – there is no better word for it – the network of volunteers who powered Labor’s campaign to its own improbable victory.

The nuts and bolts of this grassroots organising campaign are simply described. Donnelly organised the state into five regions, each of which contained four, five or six marginal seats. In each of the twenty-five targeted seats, Donnelly hired a field organiser, who then selected a volunteer coordinator and captains of three volunteer teams, responsible for doorknocking, phone banking and street stalls. Usually, there were two or three captains of each team – a bit of built-in redundancy because as volunteers they were not always available for work.

This structure is pure Obama – not a total coincidence, as Victorian Labor hired three senior American campaigners from the 2012 Obama campaign. These three specialists – a database manager, an organiser and a trainer – were kept out of sight but provided critical new skills to the emerging Victorian organisation. Also in homage to Obama, Labor’s campaign structure was given a name (Community Action Network, as in “Yes, we CAN!”), and a staff philosophy, displayed prominently in call centres and campaign offices everywhere: “Lead. Connect. Respect.”

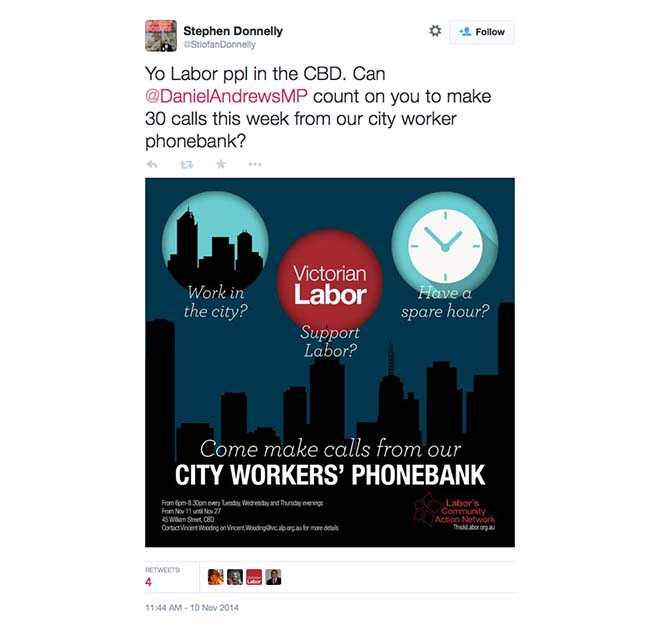

Message circulated by Labor’s Stephen Donnelly through social media to attract more volunteers to the campaign. It resulted in thousands of additional phone calls being made by volunteers espousing Labor values.

Most explicitly, Victoria’s campaign embraced the conversation-based and narrative-based campaign techniques espoused by Marshall Ganz, implemented by Obama and emulated by US Democrats and trade unions. Ganz asserts that effective political persuasion can best take place through conversation. Rather than bombarding undecided voters with TV ads and direct mail – essentially one-way traffic – a campaign organisation needs to listen to them, so as to understand their concerns (Alinsky would say, their self-interests) and to respond.

That response, moreover, shouldn’t come as fact-heavy policy announcements from the politicians but rather in the form of shared values and compelling stories from the volunteers – especially stories about why they have volunteered. It is easy to be cynical about a politician, but these volunteers’ stories are persuasive because they are entirely authentic.

Labor’s Community Action Network aimed to recruit 150 volunteers per seat – that is, nearly 4000 across the twenty-five seats. Over the last twelve months, Labor in fact recruited and trained 5500 volunteers. Of these, 45 per cent were not Labor Party members and had not been previously engaged in politics; volunteers recruited their own friends and family who recruited more friends, and so on. Over the last eight weeks of the campaign, these volunteers directed more than 500,000 telephone calls and doorknocked more than 170,000 houses. This intensity far surpasses Labor’s field campaign in the 2013 federal campaign, led by national secretary George Wright, which – over twelve months – racked up a then-impressive 1.2 million phone calls nationwide and 250,000 doorknocks

The selection of twenty-five seats illustrates the strategic simplicity of Labor’s task going in to the election. Its campaign was essentially defensive: only seven were Coalition seats targeted to win; the rest had Labor incumbents (though some of these had become notionally Liberal through redistribution). It didn’t win a landslide but enough to form government.

Without conducting independent research, such as exit polls, it is difficult to establish whether the volunteer campaign made a difference to the final result, let alone the difference in the knife-edge seats. (Labor has presumably conducted this kind of research but would be expected to hold the findings tightly.)

But it is possible to judge the professionalism of the campaign. A hallmark of professional election campaigning is its strategic efficiency: its capacity to identify a winning strategy, and to allocate its available resources in a rational way to implement it. It was not rocket science to identify the marginal seats. But Labor did some very clever things about focusing its available resources in those seats.

Notably, it drastically cut back its spending on direct mail, and redirected the funds into the field campaign. It made this decision, significantly, not on a gut feeling but on a return-on-investment approach based on trials that showed the effectiveness of conversation over direct mail in persuading undecided voters. Labor likewise was able to demonstrate the effect, in terms of voters persuaded, of hiring additional field organisers. Labor also invested in yet more database capacity, to power its ability to micro-target individual undecided voters. It honed its skills in online and telephone canvassing.

From a resource point of view, moreover, the services of energetic unpaid volunteers constitute the ultimate “Have-not” campaign asset.

After its federal debacles in 2010 and 2013, Labor seems to be recovering its capacity to conduct disciplined election campaigns focused on winning. Victorian Labor’s Community Action Network represents the most intensive effort mounted to date in any Australian election to replicate the Obama-style campaign and adapt it to the Australian party context. It sets the bar high for future campaigns.

A critical factor in Victoria was Daniel Andrews’s explicit support for the volunteer campaign and his willingness to have his own seat of Mulgrave as one of the target seats. The Greens are also working on similar grassroots organising campaigns and, as the Your Rights at Work campaign showed, the trade union movement is already ahead of the game. The Victorian Trades Hall ran a separate but entirely complementary field campaign alongside the Labor Party, highlighting public sector employees such as fire fighters, nurses and teachers. If Australia continues to follow the United States, where the Democrats still out-campaign the Republicans at the grassroots level, Labor’s expertise could play a decisive role in the 2015 federal campaign and beyond.

Of course there is nothing to stop the Liberals from organising along similar lines if they choose to make the investments; volunteering for election campaigns is no unique property of the left. But they’d better get a move on. It is Victorian Labor’s explicit intention to keep its CAN structure in place for future campaigns in which, it hopes, last month’s volunteers will become the captains, coordinators and field organisers of the future.

Saul Alinsky, of course, knew nothing of databases and micro-targeting. He may have been sceptical that a political party could effectively or honourably adopt his community organising methods for electoral purposes. He would certainly have been appalled at the radical right in the United States tagging him as a Marxist, and Obama’s community organising as an anti-American conspiracy.

On the other hand, he might have noticed that his book is getting read by a new audience, and that his rules for radicals are being pored over not by the left but by the right. The Tea Party appears, grudgingly, to recognise that there’s one good way to beat the left at its own game: read Saul Alinsky. •