A few weeks after Russian proxies in eastern Ukraine shot down a Malaysian airliner on 17 July, Russia infiltrated some 6000 more of its regular forces, including crack troops armed with high-tech weaponry, across the still-porous Ukrainian border. Whether it was an invasion or merely an incursion as some have argued, this operation sharply reversed the direction of the conflict in eastern Ukraine, which had been running increasingly in Kiev’s favour, and inflicted heavy losses on the Ukrainian forces. Western governments are in no real doubt about what has happened. And yet many Western media, and some in the commentariat, continue to treat these events as a mystery about which little is definitively known.

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has wielded its “political technology” very effectively. (Roughly translated, this technique involves liberal doses of disinformation and outright lies to achieve a particular political objective.) Perhaps its crowning achievement has been what has become known as “hybrid warfare,” which has been on display in Ukraine, particularly since the lightning operation in Crimea over three weeks in February and March this year. In this kind of war, violence is relatively limited, and is cloaked behind a thick veil of information warfare (propaganda) to conceal not only its real perpetrators but also its purpose and objectives. (For an early and apt description and analysis of “hybrid warfare,” see Janis Berzins’s paper, “Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine: Implications for Latvian Defense Policy.”)

In the Crimean case, masked “little green men,” in fatigues without insignia, conducted highly skilled surgical strikes on key enemy targets with no warning or declaration. This was implausibly presented to a gullible international audience as a spontaneous outburst of resentment by mistreated ethnic Russians suffering under the heel of a “fascist” dictatorship set up by an illegal coup in Kiev.

The Kremlin has been labelling its enemies and victims as fascists for decades, seldom accurately but often with a high degree of success. Western media, with their ethic of “balance” (“the West says this, the X says that; we’re not sure which to believe, we’re just reporting the established facts”) always run the risk of blurring or even suppressing the real story that should be obvious to anyone with a passing familiarity with the region and the situation. What we get is along the lines of “Armed men in unmarked battle fatigues have seized key buildings and installations on the Crimean peninsula. Western governments are accusing Moscow of being behind the raids, a charge which Moscow strenuously denies.” Six months later, the same convention continues to be followed.

Western publics are becoming increasingly familiar with and irritated by “spin” from their own governments, for which they are developing much more sensitive antennae. They find it much more difficult to handle outright lies and deliberate disinformation (a semi-truthful narrative, with large currants of lies embedded in it) from sources far less scrupulous than governments of open democracies.

The same sometimes goes for Western officials, particularly of the post–cold war generation. Most EU officials and politicians, for example, have become used to tough and complex bargaining and the lengthy hammering out of difficult compromises. But this all takes place within a peaceful atmosphere, following clearly set rules, with limited corruption or outright dishonesty. They can be tough on trading issues, but they are typically much less confident and effective in dealing with seriously unscrupulous purveyors of security challenges. Theirs is a fine civilisation, configured for peace, but suddenly confronted with war. As in the 1990s with the Yugoslav wars, they seem a bit lost. It must be seriously doubted that they are equal to the task of dealing with Putin’s Russia.

There are two key reasons why Russian aggression and mendacity have worked so well thus far. First, there was the shock factor. Western leaders, officials and commentators were taken by surprise by the Crimean invasion, and only after further surprises are they starting to realise what they’re up against.

Second, there’s the ignorance factor. The global West has by and large always had a poor understanding of Russia. Putin’s neo-Soviet yet postmodern modus operandi has reinforced that longstanding state of affairs. Since declaring victory in the cold war, which was largely won for them by brave Russian reformers and their East European counterparts, the West has been content to relegate Russia and its neighbourhood to the easy basket.

When conflict between Russia and Ukraine first entered the Western public awareness earlier this year, and Australian media were looking to bone up quickly, I noticed that a lot of the questions directed to me reflected very serious, even crippling misunderstandings. I was frequently asked not to discuss the overall situation or some important development, but rather the threat posed by the neo-Nazis known to be dominant in Kiev. Or could I please comment on and explain the reasons why Russians were in fear of their lives in Eastern Ukraine, where most people were Russian or pro-Russian and were in despair because use of the Russian language had been banned? Was it not the case that we’d been given fair warning of all this because the Maidan had after all been dominated by violent, far-right anti-Semites? The questions were often so wide of the mark it was hard to know where to begin.

Sometimes the questions carried the unstated implication that these alleged social pathologies not only existed, but also were peculiar to the west of Ukraine and therefore presumably absent from Eastern Ukraine or Russia itself. Moscow was assumed to be looking on from a distance with understandable dismay – suggesting that we should be supporting the Kremlin in its stalwart opposition to “the fascists.”

Some reporters rightly grasped that corruption was a massive problem in Ukraine. But they did not seem to have picked up the fact that resentment of corruption was probably the biggest factor in the Maidan protests in Kiev, that disgraced president Viktor Yanukovych had been responsible for a huge increase in the problem in Ukraine, or that corruption was an equally great or greater problem in Russia.

Many were also understandably sharply focused on Ukraine’s economic fragility, and wanted to draw an inference that any Western involvement would be a waste of money and effort. Let the Russians take over the problem and bear the costs of it; why should the West get involved? They seemed unaware that Yanukovych had sharply accentuated Ukraine’s economic debacle, not least by his own entourage’s theft of mega-billions; or that the seizure of Crimea would make things much worse; or that “giving Ukraine to the Russians” might amount to the trashing of the entire post–cold war security system in Eurasia.

From the early media coverage it became apparent, in short, that some interlocutors had swallowed whole some of the cruder falsifications of Russian propaganda. Little of the commentary seemed to betray any awareness of the degree to which, since Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, Russia was rapidly becoming a police state with increasingly fascist as well as neo-Soviet characteristics. Putin has become even more the Mussolini strongman with slightly flabby but much-exposed pectorals, heading what is essentially a one-party state; the rubber-stamp parliament, with grotesque stooge parties on the sidelines, has passed reams of repressive legislation while chorusing anti-Western slogans; all the human rights gains of the 1990s have been eliminated; Stalin and Stalinism have been restored to a place of public respect; and a uniform view of history and the world has been imposed on the media and the education system.

Since the fall of communism, Russia has of course become a society with gross inequality and increasingly run-down health and educational infrastructure. Under Putin, together with the Soviet flourishes, there has emerged a supplementary hard-right official ideology, sometimes misleadingly touted as “conservatism.” This comes complete with siren calls directed at the extreme right currently blossoming in many Western countries. This bizarre Putinist embellishment of the last few years, still scarcely noticed by many Western commentators, has featured, for example, visits from the French National Front’s Marine Le Pen to Moscow, where she was feted by senior members of the regime including deputy premier Dmitry Rogozin; xenophobic treatment of Russia’s own internal “immigrants”; gay-bashing, both literal and metaphorical, by tolerated vigilante groups and senior regime spokesmen respectively; elevation of the unreconstructed and KGB-penetrated Russian Orthodox Church to the role of joint arbiter with the state of public and international morals; and so on.

These persistent misconceptions of what Russia currently represents owe a lot to what the late Arthur Burns once memorably called “culpable innocence” – in other words, wilful ignorance by those presuming to instruct the vox populi – but also to Moscow’s skilful injection of huge amounts of well-crafted and adroitly directed propaganda. Russian propaganda now has a Goebbelsian supremo, Dmitry Kiselyov, who once proclaimed exultantly to his prime-time television audience, “Russia is the only country in the world that can reduce the United States to radioactive cinders.” In fact, nuclear intimidation has become a staple of Putinist propaganda, and not just at dog-whistle pitch. The buffoonish Vladimir Zhirinovsky, head of the Liberal Democratic Party (which is neither liberal nor democratic and scarcely a party, rather an officially cosseted Greek chorus), recently spoke publicly of a forthcoming major war in which Poland and other countries would be wiped off the map. Putin himself has declared publicly that Russia is a well-armed nuclear power and that no one should “mess with it.”

Crude as it often is, Russian propaganda is nonetheless highly skilful, much more so than its late-Soviet equivalent. It has acquired a mass international following through their external propaganda television network, Russia Today, a fact of which many Western officials remain unaware. There are, for example, eighty-six million subscribers to Russia Today in the United States alone. With a very large and expanding budget, Russia Today employs as presenters many Western native speakers who are enthusiastic critics of their own societies and enjoy the opportunity to go global, something they mostly would not have achieved on their home turf. Some of them are problematical, like a German “expert” who is editor of a neo-Nazi publication and one Karen Hudes, presented as a World Bank whistleblower, but who specialises in off-the-planet urban myths.

But Russia Today has also recruited more resounding names, including Julian Assange and Larry King. The formula is not to sing paeans of praise to Russia so much as to denigrate the alternatives. As the distinguished English Russia-watcher Oliver Bullough wrote in an excellent article on Russia Today for the New Statesman, “Deep into his fourteenth year in power, the president seems to have given up on reforming Russia. Instead he funds RT to persuade everyone else that their own countries are no better.”

Domestic Russian propaganda follows a similar strategy, with a strong and often xenophobic emphasis on the sins of other countries, especially in the West. As befits a KGB-run state, spymania is everywhere, and recently there has been a dismaying enthusiasm for finding and denouncing internal enemies (usually liberals and intellectual critics) and asserting they are in league with foreign enemies. Many Russians are becoming deeply anxious about what they see as a reversion to the atmosphere of the 1930s.

It has now been reported that a new series on predateli (traitors) has been launched on Russian television (where 85 per cent get their news), hosted by one Andrei Lugovoi, who is thought by British police to have been responsible for the polonium poisoning of the Kremlin critic Aleksandr Litvinienko. Moscow refused to extradite Lugovoi for questioning, then turned him into a national hero and arranged for him to become a member of the Duma (parliament) with immunity from prosecution. In keeping with his valiant service to Russia, host Lugovoi is introduced to his TV audience as chelovek-legenda (a living legend). Two days after reporting that news, the BBC reporter and his team were beaten up and detained for four hours in a provincial town in Russia.

For its part, the West has sharply downsized its own information outreach to Russian speakers over the past two-and-a-half decades. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the BBC World Service, which once beamed effective alternative versions to Soviet bloc propaganda, have lost much of their erstwhile coverage and prestige, and even if they were to be restored, might struggle for at least some time to gain any traction.

The lies and half-truths that Moscow launched to justify its invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine have faded somewhat, but retain a tenacious half-life. Some journalists and commentators seem to have ideological or programmatic reasons for sticking with parts of the Russian narrative. Others may simply feel the need to observe “balance,” and while Russia is still cranking up parallel narratives to put into circulation, they will go to pains to remain agnostic about which version of reality is the truth.

There are some interesting sub-categories of observers who advance the Kremlin’s cause. A distressingly large number of academics and former officials, including retired diplomats suffering from what is known in the trade as localitis (a tendency to become an advocate for the country in which they serve rather than their own), seem to be conscious advocates of the Russian narrative. In some cases they appear to have picked up a secondary complication from what Gareth Evans once luminously described as “relevance deprivation syndrome,” or RDS.

Moscow liberals, for example, tend to see Henry Kissinger as having fallen victim to RDS. He has continued to visit Moscow regularly, where he is reputed to be given elaborate red carpet treatment. His comments on Russian matters always seem to display warm empathy for the dilemmas of his Kremlin friends. For example, he has been undertaking to do all he can to ensure that Ukraine does not choose any Westward orientation even though that is what a majority of its population emphatically wants. Kissinger and former US ambassador to Russia Jack Matlock came in for some sarcasm from the prominent Moscow political scientist Lilia Shevtsova for such pronouncements, which, as she points out, closely parallel the Kremlin’s own declarations.

Some academic strategists follow similar lines of reasoning and activism, seeking to explain why certain victims have to be victims and certain bullies have to be bullies. They deploy their acumen rather like the RDS diplomat by setting out their very close understanding of the mindset of the adversary: Mr Putin’s objectives are quite understandable, they argue, and surely should be accommodated. No similar understanding or empathy is apparent for the victims.

The intentions of these strategists may be good, and it is certainly important to understand the enemy in order to respond to him more effectively. But at a certain point, perhaps, the important thing becomes not how to understand Putin, but how to stop him before he destroys all the agreements and understandings on which the international security system rests.

Otherwise the strategist may fall prey to one of the Kremlin’s most tried and true negotiating principles: “what’s ours is ours, and what’s yours is negotiable.” In the Ukrainian case, this becomes “what’s now already yours is clearly yours (Crimea and perhaps much else besides) and you and we can negotiate between ourselves about what should be left for (in this case) the Ukrainians, over their heads and in their absence.”

Recently a group of empathetic US luminaries arranged to meet with some of their old Russian colleagues to discuss a peace plan for Ukraine. Without going into the merits of their plan, the idea that a group of Americans should presume to launch such an initiative, at a time when Russian aggression had ratcheted up further, and without seeking the participation of a single Ukrainian representative, was emblematic of their appeasement mind-set.

The line of argument of the Russlandversteher (those who understand Russia) is typically that Putin is the ruler of a very large nuclear-armed country, which they like to affectionately call “the bear,” whose concerns about Western policy are entirely reasonable. In any case, they argue, irrespective of how reasonable they are, we should be very wary of “poking the bear.” NATO’s expansion to the east was an intolerable threat to Russia, and Moscow is attacking its neighbours not because it has a revanchist program to reinstitute a Soviet Union–lite, but because of its understandable hostility to Western intrusions into its “backyard.”

The sensitivities of 140 million Russians are paramount in this train of thought, not the interests of the 160 or so million East Europeans who live between Russia and core Europe. That NATO expanded not because of NATO’s desire to threaten Moscow but in response to the desperate desire of many East Europeans to be freed from would-be autocrats-for-life like Lukashenko or Yanukovych, or from renewed Russian aggression, is not seen as relevant.

The expansion of NATO was, they assert, a breach of solemn promises to Moscow. Oral reassurances about NATO’s future intentions were certainly made in cautious language at a certain point, but in the very different context of prospective German unification, and before the peoples of the region had fully had their say. Once they had, new states emerged whose sovereignty and integrity Moscow duly agreed to respect. For wholly natural reasons, many such states have chosen to pursue some sort of Western vector. Outraged by these sovereign choices, Moscow has breached its undertakings to respect their sovereignty repeatedly. (The issue of the West’s supposed undertakings to help sustain Russia’s East European sphere of influence is discussed by Mary Elise Sarotte in the latest edition of Foreign Affairs and by Ira Straus at Atlantic-community.org.)

On the other hand, Ukraine did actually receive some written assurances, which are on the public record. In 1994, under pressure from Moscow and the Western powers, Kiev agreed to divest itself of its nuclear weapons in exchange for written assurances that it should never become the subject of economic or military coercion and that Russia, the United States, Britain and France would stand ready to defend it in any such event. Those assurances have proven worthless.

The argument that NATO’s expansion to the east is an intolerable provocation to Moscow is in any case inherently unpersuasive. If Moscow was indeed so afraid of NATO expansion, why was it not reassured by the fact that for many years NATO has observed the self-denying ordinance, inscribed in the NATO–Russia Founding Act of 1997, not to deploy any significant military hardware or personnel in the new member states. It is quite clear that the new members are the ones threatened by Russia’s aggressive revanchism under Putin, not the reverse. On 18 August, during a visit to Riga, Angela Merkel reaffirmed that the Act meant that even now, despite Moscow’s multiple aggressions and transgressions, there would be no permanent bases in the Baltic states regardless of their desperate pleas.

Russia, meanwhile, has continued its aggressive overflights in and near the air space of its western neighbours, NATO and non-NATO members alike, particularly though not only in the Baltic/Nordic region. It conducted a cyberwar with backup action by the Russian minority against Estonia in 2007, and this month it abducted an Estonian security official from Estonian sovereign territory just two days after President Obama visited Tallin to reassure Estonia that it would not be left to stand alone if it were subjected to attack. The invasion of Georgia by Russia in 2008 – after a long history of aggressive provocation by Moscow and its proxies in Abkhazia and South Ossetia – and the huge military exercises up against western neighbours’ borders in 2009 and 2013 – one of which concluded with a simulated nuclear strike on Warsaw – all have a similar resonance. So too, of course, do the frequent trade wars Russia has unleashed against erring former vassals.

The confidence with which it pursues these aggressive policies strongly suggests that while Russia may be angry about NATO’s expansion, it is not afraid of it. Moscow regards the territory it gained under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, whereby Hitler and Stalin divided up the East European countries between them, as still valid. Its stridently aggressive behaviour suggests that it wants to restore them to its patrimony, and that it regards NATO as not much more than a paper tiger in the region. Yet despite this sustained aggression, the compassion of the Russlandversteher for Russia’s imperial phantom limb syndrome knows no bounds.

Another frequent line of justification by Western commentators for Russia’s pursuit of its neo-imperial objectives is that we must be more sympathetic towards Russian policies, because if we’re not, they’ll gravitate even closer to China. Official Russian spokesmen and patriotic scholars have deployed this argument for decades through all kind of vicissitudes in Russo-Chinese relations. On one legendary occasion, a Soviet official in Canberra, enraged by what he perceived to be an attempt by local interlocutors to exploit the then Sino-Soviet divide to threaten Moscow with bad outcomes in Afghanistan, responded, “Just you wait – one day we’ll get back into bed with our Chinese comrades and screw you from both ends.” More cerebral versions of this argument have been heard increasingly from Moscow propagandists in recent months, adjusted to fit the circumstances of the time. And predictably, some Western commentators have adopted it.

A common Western counterstrike has latterly been to hint that Russia’s growing strategic partnership with China will lead to its becoming China’s junior partner or even its neo-colonial vassal loyally supplying raw materials. Russian polemicists are even beginning to deploy this argument in attack mode to argue that if Moscow does indeed become junior partner to Beijing, that will be the West’s fault, and to its detriment above all.

Western experts on the region are likely to have a better grasp of Russian than of Georgian, Moldovan, Estonian or even Ukrainian affairs. As a result they often acquire a bad case of secondary Russian chauvinism, taking on unconsciously something of the dismissive attitude of the vast majority of Russians, both the highly educated and the bovver-boys on the street, towards smaller ethnic groups within Russia and on its borders. This makes them vulnerable to Russian propaganda, even though they are of course aware of that phenomenon in general terms and would believe that they were making adequate allowance for it. It also makes them more receptive to the thought that any troublesome smaller neighbour should, if necessary, be put back in its box to keep the bear contented and friendly.

That doing so might not only undermine the post-1990 security system but also help to recreate an aggressive, confident, anti-Western and expansionary Russia does not seem to trouble them. Likewise, that it might lead to an unravelling of the Western strategic community, with countries betwixt and between Russia and the European Union increasingly choosing to accommodate Moscow’s aggressive or seductive overtures because they can see no prospect of its being resisted by anyone. Some East European NATO members, including Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria, seem to be already flirting with just such a fundamental reorientation.

Working journalists are less likely to be involved in working creatively towards peace in our time by launching hands-across-the-Bering-Strait initiatives. After a scramble to catch up at the outset of the Crimean invasion, for the most part they are doing a pretty good job. But the language used to describe the unfolding events in Ukraine continues to be impregnated with assumptions and misconceptions stemming ultimately from Russian disinformation, and above all from its remarkably successful efforts to conceal its direct involvement in the conflict in Ukraine.

“The civil war in Ukraine,” “the Ukrainian crisis,” “separatists,” “pro-Russians,” “rebels” – terms like these are loaded with semantic baggage that helps Moscow to maintain, even now, that it is only a concerned bystander, worried about the tragic fate of its sootechestvenniki (“fellow-countrymen”) and seeking to find an honourable way out for all concerned. Even before the attack on Crimea, Russia had been working hard through trade boycotts, manipulation of energy pricing and heavy pressure on its wayward protégé Yanukovych to force Kiev to abandon its arduously negotiated Association Agreement with the European Union.

When Yanukovych finally complied, and huge demonstrations broke out in response on what came to be known as the Euromaidan, Putin pushed him to introduce police state legislation modelled closely on Russia’s own. When that in turn failed, Yanukovych resorted to mass shootings in an effort to suppress the protests. Such actions had not previously been part of his repertoire, so this was probably also a response to pressure from Moscow. And when that too failed, he fled, leaving Kiev to the Maidan coalition

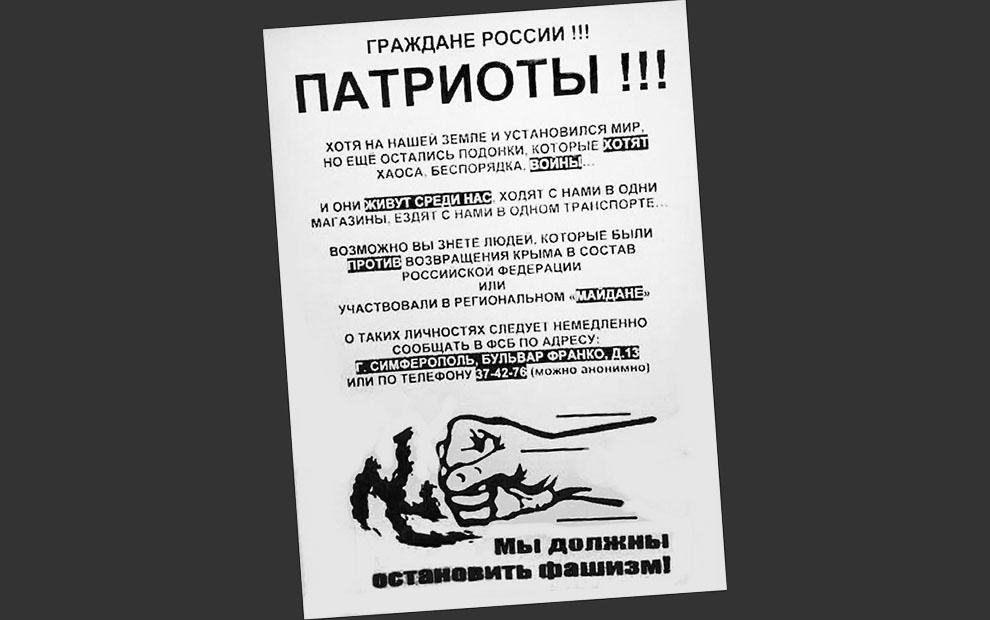

The Crimea operation bore even more of Moscow’s fingerprints. Despite the unmarked uniforms and heavy weaponry, it was clear that Russian special forces were heavily involved, as well as the armed Russian units stationed on the peninsula (obviously all a crass violation of the Black Sea Fleet Agreement with Kiev). There was also an admixture of local Russian patriots and compliant politicians and administrators, some local and some spirited in from across the border. Russia’s Federal Security Service, the domestic successor organisation to the KGB, quickly established its presence by calling on the population to denounce any of their neighbours who had supported the Maidan revolt. In the months since the annexation, Crimea has descended into an economically depressed police state, complete with aggressive homophobia and all the other hallmarks of loyal, provincial Putinism.

Leaflet distributed in Crimea by Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB. It reads, “Citizens of Russia!!!/ PATRIOTS!!!/ Though peace has been established on our land, there are still scum who want chaos, disorder, war…/ And they are living among us, go with us to the same shops, travel with us in the same public transport…/ It’s possible you know people who were against the return of Crimea to Russia/ Or/ Who took part in local Maidan activities/ You must inform the FSB immediately about such individuals at the following address:/ Franko Boulevard 13, Simferopol/ Or telephone 37-42-76 (you can remain anonymous)/ WE MUST STOP FASCISM!”

A fortnight after the annexation, a very similar pattern of events began to be enacted in the Donbass and other regions in Ukraine’s southeast. Here again Russians from Russia were conspicuous in the leadership, and the military professionalism of most of the attacks made it clear that Russia was directly implicated in precipitating, staffing and managing the takeovers. The proportion of local zealots participating in the events, however, was greater than in Crimea, which contributed to the indiscipline of the proxy forces and perhaps also to their penchant for common criminality and gross human rights abuses (abductions, beatings, disappearances, arrests) against local residents.

As Kiev recovered its composure and managed to improvise an effective military response, the polarisation of the population between east- and west-oriented naturally increased. But that does not make the conflict that resulted a civil war. Before Yanukovych began shooting protesters, and before Putin launched his hybrid war against Ukraine, there had been very little loss of life through politics in the quarter-century of Ukraine’s independence. There were certainly political differences between many in the west and east, but they had essentially been regulated through the ballot box.

Insofar as the conflict has or may become something more like a civil war, if with decisive interference and involvement from Russia, it will be a civil war conceived by artificial insemination. Nor can it properly be called a “Ukraine crisis.” Perhaps the later and violent phases of the Maidan could be so described, but once Yanukovych chose to flee, the crisis was over. What followed was not a crisis, and certainly not a Ukrainian crisis, but an invasion of Ukraine by Russia coupled with active and violent destabilisation, in which local recruits, stiffened and led by Russian troops and administrators, were carefully steered towards Moscow’s objectives.

Nor can the combatants of Russian persuasion accurately or properly be referred to as “separatists” or “rebels.” While the exact proportions are difficult to determine, it is Russians from Russia who have been calling the shots, while cross-border reinforcements of weapons, supplies and personnel have been maintained throughout. To be a separatist you have to be in your own country and trying to detach part of it to form an independent entity. The so-called “separatists” in Eastern Ukraine may be irredentists, but their movement cannot be considered as genuinely separatist. For similar reasons, a foreign soldier cannot be classed as a rebel.

There is a genuine terminological difficulty here, but the solutions in common use are tendentious and serve to conceal Moscow’s decisive involvement. In other such cases, the fighters might well be described as “fifth columnists” or even simply as traitors. There is, moreover, evidence that quite a number of the combatants are not “volunteers” but paid mercenaries, originating often from the Russian north Caucasus and shipped in across the border.

Such terms as “fifth columnists” (now commonly used by Russian officials to describe liberal dissidents, by the way) might seem harsh or not fully accurate given the authentic strength of local pro-Moscow sentiment in southeast Ukraine, and past vicissitudes and disputes relating to state boundaries. But “rebels” and “separatists” are not appropriate, and nor should a militiaman who has allowed himself to be recruited to fight for a foreign imperial power be entitled to any other semantic fig leaves. It is striking that Kiev’s preferred term “terrorists” is studiously avoided by the Western press, even though a much better case can be made for that than for most of the locutions actually used (violence against legitimate institutions and civilians, mass abuse of human rights, avoidance of identifying insignia, deployment of weapons in residential areas, and so on).

The terminological difficulty has led to the widespread use of the term “pro-Russian,” usually as an adjective, but sometimes even as a noun to describe those fighting against the Ukrainian armed forces and their volunteer militia supporters. But that too is inadequate. Many of them are quite simply Russians, for starters. Why not “pro-invaders”? I personally would favour “proxies” or even simply “Russians,” which is what most would identify as, and which describes exactly where they stand. The only difficulty with “Russians” is that many ethnic Russians in Ukraine do not want to betray their country or see their home region attached to Russia.

The most recent turn of events in the fighting has unleashed a further avalanche of misleading descriptions which again have the effect of concealing Russia’s real role in events. As will be recalled, there was a time in the early months when the proxies seemed to be sweeping all before them, the Ukrainian armed forces seemed demoralised as well as hopelessly ill-equipped, and the local populations in the east seemed not to be fighting back against the proxies, despite opinion polling which showed that even in Crimea a majority of the population did not want to become part of Russia.

Then the Ukrainian armed forces began to find their feet, supported by volunteer militias and the financial contributions of many ordinary Ukrainians, as well as some key oligarchs. From May to mid August, the Kiev forces gradually took control of the situation, forcing the proxies back, and even recapturing most of the lost ground in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces.

They faced difficult dilemmas in doing so. With the Russian forces well dug in, winkling them out in urban areas would inevitably require aerial and artillery bombardment to reduce the need for bloody street fighting. In addition Kiev would need to solicit and maintain the support of the oligarchs where possible, and also the enthusiastic but sometimes problematical volunteer detachments.

All such steps could increase the suffering and bitterness of both fighters and civilians in the disputed east. The pro-Kiev militias, like those on the other side, were in some cases led and/or manned by militant nationalists with hardline political views. Over the longer term, this could create a security problem for the Kiev government and reactivate the familiar Russian propaganda trope of “the fascists and Banderovtsy in the Kiev junta and Western Ukraine.”

A particularly worrying formation for Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko has been the force led by the populist nationalist Oleh Lyashko. Lyashko has been using his militia not only against the enemy but also as a tool in his campaigns for the presidency (where he did dismayingly well, finishing a distant third behind Poroshenko, but third nonetheless) and in the parliamentary elections scheduled for 26 October, where polling suggests his Radical Party will do well. He and his militiamen have been involved in kangaroo courts, direct actions of dubious legality and other abuses of human rights.

Though not a fascist in the ideological sense, Lyashko is certainly an extremely dubious asset for Poroshenko. With a shady past, including a criminal record and onetime connections with Yanukovych’s party, his prominence in the war has enabled him to throw out very aggressive political challenges to the Poroshenko bloc. Fortunately, his popularity seems to be declining, but it remains uncomfortably high.

Another very mixed blessing for Poroshenko is the Azov Battalion, which has fought bravely but really does display neo-fascist insignia and has members given to hard-right pronouncements. Lyashko himself is from Luhansk, and interestingly quite a lot of the recruits to such hardline pro-Kiev detachments are ethnic Russians from the east of the country. (For a balanced appraisal of hard-right militias generally in Ukraine, see Alina Polyakova’s recent article for the Carnegie Moscow Centre, “The Far-Right in Ukraine’s Far-East.”)

Armed conflicts have a tendency to generate irregular forces like these, particularly at critical junctures in immature semi-democracies like Ukraine’s. Ukraine is fighting for its independence, perhaps even ultimately for its existence, with no reliable allies and an enemy much stronger and better-equipped than itself. There are many more such militant and extremist formations in Russia and on the Russian side of the fight in Ukraine, but while Moscow doesn’t choose to rein them in for the most part, it undoubtedly can do so when it judges it expedient. Poroshenko, despite his strong presidential mandate, doesn’t enjoy a similar capacity and has many other extremely urgent and difficult problems with which to deal.

So why do Western commentators focus so disproportionately on the pro-Kiev bad guys? They may represent some sort of threat to their local Russian enemies, but not to the Russian regular army, which can and has inflicted devastating damage on them. Even less do they threaten the Western countries, whose commentators focus on them with such keen attention. The hardline nationalist militias and their political allies remain a country mile behind Poroshenko in public opinion ratings. The only thing that might make them serious contenders would be if Russia continues to inflict defeat, destruction and yet more trade wars on the elected Kiev authorities while the West looks on disapprovingly, but does nothing effective to save them.

With some observers, it’s difficult to avoid the impression that for whatever reasons they want to exculpate the aggressor by blaming the victim. The blame-the-victim commentators are not much interested in the fact that the victor by an overwhelming margin in the recent presidential election was a moderate nationalist ready for compromises to preserve peace – perhaps even too ready in the view of some; or that the Ukrainian prime minister Arseny Yatseniuk, for example, is a pro-Western liberal economist and democrat, of partly Jewish heritage; or that the man who for a time took over as acting prime minister from Yatseniuk was a senior regional administrator called Volodymyr Groysman, also a Jew; or that at a time when the European Union is in considerable economic and political difficulty and losing much of its erstwhile allure, virtually the entire Kiev political class in its present configuration is desperate to join it.

By contrast with such groups as the Azov Battalion, the spectacularly bad guys among the Russian military colonists and their local supporters attract little enough media scrutiny. Take, for example, Igor Girkin (aka Strelkov), a Russian from Russia, former supremo of the self-styled Donetsk People’s Republic, the very name of which reeks of Stalinism. In his long career as a soldier of fortune pursuing Russian imperial causes in the most expansive sense, Strelkov has been reported to have involved himself with Bosnian Serb forces in ethnic cleansing of Bosnian Muslims during the Yugoslav wars. He is undoubtedly a Russian fascist, but also a nostalgic Stalinist, which makes him one of a hybrid type widespread in Russia at the moment.

Then there is the former Russian criminal Sergei Aksyonov, who is presiding over the communising of Crimea, also ignored by most of the West. Or take Alexander Borodai, another Russian from Russia, who miraculously emerged as the supremo in Donetsk and remained there till Moscow found it expedient to replace him with a local called Aleksandr Zakharchenko, a true-red loyalist to Moscow, but with a usefully Ukrainian-sounding surname. And probably most importantly, there is Vladimir Antyufeyev, the grey KGB eminence of Transnistria, and now, as of recently, of eastern Ukraine. Why is no one particularly aghast at their prominence?

Antyufeyev in particular gets minimal attention in the West. Yet his role as Moscow’s de facto viceroy in southeast Ukraine is obvious. It is clearly reflected in a recent picture of Strelkov holding court with his uber-imperial followers back in Russia where he is “on leave,” a photograph displaying the attractive features of Antyufeyev on the wall in the background, where Stalin might once have been.

Despite the country’s overwhelming burdens, for months the Kiev forces continued to make steady progress towards their objective of encircling Donetsk and Luhansk cities with a view to cutting them off from resupply across the Russian border. Moscow responded by changing their proxies’ leaders and providing more high-tech weaponry. This led to some spectacular victories in local skirmishes by the Russians as well as to rapidly growing downings of Ukrainian aircraft. But it also led to the MH17 disaster, which was obviously not a triumph for Moscow. Until well into August and despite the successive waves of Russian intervention, Kiev’s steady counterinsurgency progress seemed to be maintained.

Then suddenly came a 180-degree shift in the fortunes of war. Russia introduced into Ukraine a large number of its regular troops, probably some 6000 or so all up, including crack special forces, and with more high-tech weaponry. Abruptly, wholly against the flow of play, the beleaguered “rebel” forces turned their increasingly dire situation around. The siege of Donetsk was broken, and a large concentration of mainly volunteer pro-Kiev units near the strategic town of Ilovaisk was forced to retreat. As they retreated, responding apparently to an invitation to exit via a “humanitarian” corridor, they were ambushed by Russian forces with greatly superior weaponry, resulting in a massacre of hundreds of men and total destruction of their weapons and military transport.

The survivors of the Ilovaisk massacre feel bitter that they did not receive more back-up from Ukrainian forces, a resentment that may create strains as volunteer militias come to be reintegrated in the armed forces or civilian society of any post-conflict Ukraine. It was an attack well-executed and well-directed in every sense by highly professional Russian troops, part of a broader intervention that forced Poroshenko to sue for a ceasefire. He has been on the back foot ever since, offering concessions to the “separatists” and desperately pleading, largely in vain, for more help from the European Union and NATO.

Western countries, Amnesty International and other authorities have all said that this turnaround was the result of a clandestine but large cross-border deployment of Russian troops and armour. Russian internet sources and surviving independent Russian media and blogs accept the sharply increased Russian involvement as the cause of the sudden “rebel” triumph. The Russian Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers, one of the few politically engaged NGOs still working effectively, has claimed that some 200 soldiers from regular Russian formations have now perished in the fighting in Ukraine. For making such a damaging claim, the St Petersburg branch of the NGO has already been denounced by the regime as a “foreign agent” (translated from the 1930s Stalinese, “spy” or “traitor”).

Among the Russian casualties have been members of the crack Pskov Paratrooper Division. A (legal) opposition politician in Pskov who attempted to view the graves of anonymously buried special forces soldiers there was beaten up by “unknown assailants” – a trademark of the Federal Security Service – and left unconscious with a fractured skull. The war is increasingly unpopular in Russia, and Putin is continuing to keep it hush-hush, both for that reason, and to maintain the threadbare fiction of Russia’s non-involvement.

The current shaky armistice, which the Russian side in particular has been breaking in an attempt to regain control of Donetsk airport and other strategic targets, is unlikely to be sustained. Poroshenko’s effort to shore it up by offering further concessions to the “separatists” may give Kiev some further respite, but that too is unlikely to remain stable for long. The only thing that will ensure stability is for him to further surrender Ukrainian sovereignty, recognising the “rebels” as a legitimate Ukrainian force representative of the local populations (which they never have been – their referenda were a farce), and accepting Russia as the paramount guarantor of stability in the region; in other words, in addition to the loss of Crimea, accepting that Ukraine would now have a large frozen conflict in its industrial heartland.

Even that would almost certainly not be the end of it, judging by the experience of frozen conflicts elsewhere in the post-Soviet area. The corresponding parts of Moldova and Georgia have been used as tools to try to block any Westward movement by those countries. A frozen conflict can also, if and/or when the need or opportunity presents, be rapidly unfrozen to form a Piedmont in a wider irredentist push. Georgia presented a classic case and Moldova may soon provide another.

Russia’s diplomatic choice to establish a frozen conflict is the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, or OSCE, where, in recent times, US influence in relation to events in Russia’s western borderlands seems to have been relatively weaker, and where Russia has made good use of its veto power to make the OSCE’s work more difficult. The recent peace discussions brokered by the OSCE are unlikely to deliver either a permanent settlement or a just one. The OSCE is not in the business, for example, of suggesting that Russia was not a legitimate player in the “peace process” to begin with.

The OSCE format was publicly launched by Putin in May, when he welcomed in Moscow a visit by the Swiss president and chairman of the OSCE for 2014, Didier Burkhalter, and an OSCE blueprint for a settlement which Burkhalter brought with him. At that time, the Kiev forces had started to turn the tide against the Russian proxies, and Putin clearly was looking to hit the pause button before things got any worse for his proxies. The OSCE format keeps the United States out of the front line of the Ukraine issue, and the formation of an OSCE Contact Group consisting of a Swiss OSCE chair, Russia, the Donetsk and Luhansk so-called People’s Republics and Ukraine has enabled Putin to shape negotiations with Poroshenko in what is for Moscow a very favourable context.

Russia’s frequent use of its veto to pressure the OSCE and the lack, over time, of any effective US or Western push-back on OSCE involvement in frozen conflicts have ensured that the OSCE is now very sensitive to Russia’s priorities. Germany and France, who happen to be two of the EU/NATO countries most understanding of Russia’s security requirements, have had a modest involvement in the Contact Group process, mainly in pressing Ukraine to become engaged. But Britain, like the United States, is not involved. Thus Berlin’s Russlandversteher approach is virtually the only Western game in town. The Contact Group is headed by Swiss diplomat Heidi Tagliavini, who produced a report on the Georgian war of 2008 which, in the view of some observers, tended to whitewash much of Russia’s responsibility for that event and for the extensive destruction it visited on Georgia.

In this unpromising OSCE format, not being comfortable in situations where force has been or may be deployed, Germany is looking for a peaceful solution and is happy to entrust the task of mediation between aggressor and victim to the OSCE. Kiev, however, is clearly outnumbered. At one point, the Group even brought into the talks as a separate participant one Viktor Medvedchuk, a close friend of Putin’s and the most pro-Moscow politician in Ukraine, where he has almost no popular support.

For Putin, the latest purpose, as in May, is to present Russia again as a concerned, peace-loving observer while this time locking in his sudden gains on the battlefield. The timing of his back-of-the-envelope peace proposal, reportedly sketched out on a flight to Mongolia, was also meant to weaken and further divide the leaderless and irresolute Western leadership just as NATO was holding a crucial summit on 4–5 September in Wales and the European Union was struggling to reach agreement on another round of sanctions.

In this, Putin was highly successful. Again the huge advantages of a single, autocratic leadership over broad coalitions of poll-ridden democracies were in evidence. After protracted agonies about whether to impose further sanctions on Russia for again invading Ukraine, the European Union finally approved a package, but in the same breath said that the sanctions might be reviewed within weeks if the ceasefire holds. That the “ceasefire” followed another damaging Russian military expedition was, like the Crimean annexation, seemingly forgotten or forgiven.

Brussels also mysteriously suspended till the end of 2015 the implementation of the DCFTA (Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement) with Ukraine, to which it had previously accorded accelerated passage. The reason for this unexpected additional reward for Russia’s bad behaviour was seemingly to enable further exhaustive discussions aimed at accommodating the Russians’ objections to the free trade deal. Moscow has demanded a virtual rewrite of roughly a quarter of the huge and exhaustively negotiated agreement.

The European Union has previously maintained that the agreement would not damage Russia’s trade and, more generally, that it could not, as a matter of principle, allow third parties to interfere in its negotiations with other countries. The Poroshenko government agreed to the postponement, reportedly because it feared that otherwise Moscow was planning to hit it with a crippling all-out trade war. The European Union has cushioned the blow of the postponement by extending trade concessions to Ukraine over the intervening months.

Nonetheless, the postponement sends yet another discouraging signal to Ukrainians and other countries under Russian pressure. A deputy Ukrainian foreign minister resigned over the issue, which is not reassuring on the question of what backroom deals were struck to secure Poroshenko’s agreement. The postponement also offers further encouragement to Russia to maintain its present aggressive stance towards the countries to its west, and their Western friends.

NATO, for its part, stalwartly reaffirmed that it would not deploy any boots permanently on the ground on the territory of the new members, but that it would provide “reassurance” in other ways. It also confirmed that it would continue not to supply any weapons to the beleaguered Kiev administration. It undertook, on the other hand, to provide non-lethal aid worth US$20 million. Subsequently, the Ukrainian defence minister asserted that some individual NATO countries were undertaking to supply weapons to Ukraine, but the countries he mentioned have denied it.

Last week Poroshenko visited the United States where he renewed his appeal to the Obama administration for lethal aid to resist Russian aggression on his country. He was well received, particularly in Congress, but his appeal was unsuccessful, though he did receive a further US$53 million in non-lethal aid. As he said when he addressed Congress, “Please understand me correctly. Blankets, night-vision goggles are also important. But one cannot win the war with blankets… Even more, we cannot keep the peace with a blanket.”

Short of another muscular intervention from Moscow, a trade war alternative is always near to hand. Recently Russia sharply reduced its gas exports to Poland, putting a stop to reverse-flow imports by Ukraine through Poland and Slovakia to replace the flows through Ukrainian pipelines that Russia blocked last June. If Poroshenko does not give satisfaction in the peace talks, the economic stranglehold on Ukraine can be strengthened at will, a far more immediate and deadly weapon than any Western sanctions that have yet been devised against Russia.

Conscious of his weak hand internationally and the forthcoming elections domestically, Poroshenko is bending over backwards to stay out of trouble. Following up on the Minsk ceasefire agreement of 5 September, he managed to push through legislation on 16 September offering a guarantee of autonomy for three years to local government in areas of Donetsk and Luhansk controlled by the proxies. The law is carefully drafted to avoid legitimising the authority of the “people’s republics,” but is domestically costly for Poroshenko even so, and will increase the criticism of him from radical rivals in the run-up to the vital parliamentary elections on 26 October. It is also very unlikely to satisfy Moscow or most of its proxies, which are continuing military actions to seize more territory beyond the ceasefire lines.

Meanwhile, Russia is at work in the Baltic states. Despite Barack Obama’s visit to Tallin, where he delivered a ringing address – a genre in which he excels – Moscow has launched a concerted series of provocations, beginning two days later with the abduction from Estonian territory of an Estonian anti-corruption official, and his almost immediate parading before Russian TV cameras as a spy.

Soon after, a senior Moscow official responsible for “human rights,” Konstantin Dolgov, visited Riga where he delivered an aggressive speech denouncing Latvian “fascism” and alleged mistreatment of the Russian minority, and calling on the Latvian Russians to show their “martial spirit.” (In fact they are already doing so; a high proportion of Latvian Russians support the annexation of Crimea, and there have been reports that some are being recruited to fight in Ukraine.) Given the atrocities committed by Moscow against the Baltic peoples after the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, these are remarkably brazen and threatening claims.

Russia has recently revived and is pursuing through Interpol arrest warrants against Lithuanian citizens who refused to serve in the Soviet/Russian army at the time of Lithuanian independence. And it has in the last few days seized a Lithuanian fishing vessel, which the Lithuanians allege was in international waters at the time, and tugged it off to Murmansk with twenty-eight people on board.

So, a Baltic trifecta. Regardless of how these events develop further, their common purpose appears to be at the very least to suggest to the Baltic governments that their distinguished visitors and supporters live far away and can’t or won’t do much to help them.

With Western attention again becoming absorbed in very difficult Middle Eastern issues, it is hard to be optimistic about the further outlook for Ukraine – or for the future of European values in the post-Soviet space. •

Republished with a correction on 22 December 2014