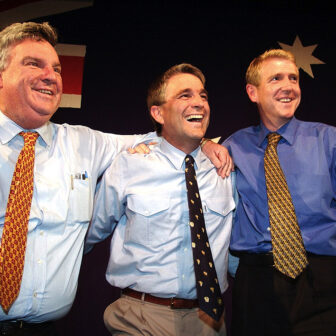

WHETHER Peter Dutton was really any good, we may never know. Barring a turnaround in events, the feisty former Queensland policeman looks to have turned his back on a continuing political career after the redistribution in his always-marginal seat of Dickson and his failed attempt to win preselection for the safe Liberal seat of McPherson.

Dutton’s imminent demise raises uncomfortable questions: for the Liberal Party as a whole, over the increasingly questionable marriage with the Nationals in Queensland (which has already cost the Liberals a talented former MP and minister in Mal Brough), and in relation to the spectacular lack of influence in the Queensland branch of party leader Malcolm Turnbull.

It might be that Dutton is not as good as some claim – and as shadow health minister he has yet to demonstrate either any flair for policy or, for that matter, any effective parliamentary scrutiny of the Rudd government or the health minister, Nicola Roxon. But, in fairness, he is new to opposition. He is willing to have a go, is good on his feet and displays some real passion – something the demoralised party at present sorely needs. He is also young – in his thirties – and hails from a modest social background with some small business experience under his belt. These are all characteristics the Liberal Party needs if it is to regain any real traction in the middle Australia heartland.

That the hasty and uneasy marriage between the conservative parties in Queensland – a putative pilot for elsewhere – has been difficult is beyond dispute; it was really a short-term tactic aimed at securing victory in the Queensland election, and in those terms it failed. Precious little, if any, thought was given to federal preselections other than a cumbersome godfather provision for sitting senators and members.

It has always been the prerogative of the party organisation to select candidates. In times of old, before power in the Liberal Party shifted decisively to the centre – that is, the leader’s office and the federal secretariat – the party employed a legion of field officers in most states whose job it was to keep in touch with the grassroots and, in so doing, to act as talent scouts. Just as the organisation has a responsibility to find prospective candidates it also has a responsibility to protect existing assets, and one must ask why the Dutton saga had to end in a humiliating fiasco.

The fact is that Dickson was always going to be not only a marginal seat but also a seat prone to potentially unfavourable redistribution, given the demographically volatile growth corridor in which it is located. With Dutton having scraped in by his fingernails in 2007, by which time he had revealed some capacity as a junior minister, why was there no plan in place to ensure his future? It’s all very well for deputy leader Julie Bishop to say no one is guaranteed a seat – that’s true enough. The point that this less than astute politician misses entirely is that her party is in no position to shrug off the loss of someone like Dutton who, one might reasonably expect, would be a key part of the Liberals’ next generation.

Why was Dutton not discouraged from making a run in McPherson? The party heavyweights, former Liberals and Nationals alike, would surely have been aware of how the numbers were falling, and if they weren’t aware then the party is in even deeper trouble than generally thought. As it was, the Liberals have chosen a strong candidate in what was an exemplary exercise in party democracy. McPherson is, and has always been, a Liberal stronghold, and there is no evidence, as has been suggested elsewhere, that Dutton was dudded by the former Nationals. While some might say that his judgement has been found wanting (but he might be forgiven on the grounds of desperation), the party organisation should have tapped him on the shoulder before the ballot. He was, as it turned out, simply left to hang out and dry. He has now ruled out re-contesting Dickson – perhaps a mistake – and the hybrid party’s marriage arrangements effectively block a place on the Senate ticket as an alternative. He has also said he will not contest preselection for the new seat of Wright, which means all that is left if he is to remain in parliament is for the party organisation to lean on under-performing veterans Peter Slipper in Fisher and Alex Somlyay in Fairfax. A move against either will trigger an internal skirmish (and especially so in the case of Slipper, a former Nationals MP).

Among all the static of the McPherson preselection row, it has all but been forgotten that Malcolm Turnbull lent his voice in support of Dutton, and it was ignored. Did Turnbull, or the federal secretariat for that matter, draw their Queensland colleagues’ attention to Dutton’s plight? While party leaders seldom choose to involve themselves in preselection wrangles, when they do they place their moral authority on the line: a rebuff can, and often is, seen as a challenge to a leader’s authority. (In the distant past, a mere nod from Bob Menzies would have saved a threatened member.)

In recent times, party leaders have intervened at their peril in preselection contests. John Howard courageously defied the mad right wing of the New South Wales party to protect the moderate senator, Marise Payne, but similar forays by recent leaders have not been so successful. A decade and a half ago John Hewson’s authority was fatally weakened when he failed to save the popular Wal Fife from a challenge by the Nationals after a redistribution that saw Fife leave parliament. A few years earlier, a newly recycled Andrew Peacock took a battering when he was unable to save his Victorian frontbench colleague Ian MacPhee. It was doubly humiliating for Peacock, a creature of the party, as he had been a former state president.

The rebuff to Turnbull might not count for much, coming as it does among many. But the loss of Dutton to the party, actual as well as symbolic, is a self-inflicted wound the once mighty Liberal Party can little afford. The Liberals might not win back government for many years, but the quality of democracy demands an opposition of sufficient calibre to hold government to account, and that in the end may well be the real loss in this sad and sorry saga. •