Barely a fortnight before the October 2004 federal election, Michael Ashcroft, a Conservative member of Britain’s House of Lords, donated $1 million to the Liberal Party of Australia. Earlier this year, the Melbourne Age exposed how links between the Italian Calabrian mafia and key Liberal Party parliamentarians were facilitated by political contributions. Over those dozen years, political donations from foreign sources – and controversies about those donations – became a feature of the Australian political landscape.

Of all foreign donations, though, the ones made to the major parties by Chinese companies have received the most attention. The 2008 federal election saw Macau’s casino tycoon, Stanley Ho, and his business associates donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Australian Labor Party. In 2009 and 2010, former defence minister Joel Fitzgibbon was caught up in a scandal precipitated by donations received from Helen Liu, a Chinese-Australian businesswoman with connections to the political and military elite in Beijing.

More recently, reports of donations made by the Yuhu Group and Chinese billionaire Chau Chak Wing (and his company, Kingson Investment) to the WA Liberal Party made headlines, especially when foreign minister Julie Bishop, the most senior federal MP from Western Australia, singled out three key Chinese donors for praise.

Then came revelations that the Top Education Institute, a Sydney-based company headed by Minshen Zhu, had paid $1670.82 of Labor senator Sam Dastyari’s travel expenses, and the Yuhu Group had contributed around $5000 to his legal expenses when he was secretary of Labor’s NSW branch. These reports, together with the fact that Dastyari contradicted Labor policy in relation to the South China Sea dispute, led to his resignation from the Labor frontbench.

This latest controversy has prompted calls for a ban on foreign political donations. Canada, Britain and the United States have all adopted such a measure, say critics of the present system, and the case for such a ban in Australia seems irresistible.

But this is to put the cart before the horse. Before we jump into how we should regulate foreign political donations, three questions need to be answered: What is meant by a “foreign” political donation? What are the specific concerns about “Chinese” political donations? And why should such donations be better regulated?

In this context, “foreign” seems to have three possible meanings: a narrow one, which refers to overseas-based donors; and a broad one, which extends to all non-citizens who donate to political parties, whether or not they are residing in Australia. The third understanding is more complex: it refers to individuals born overseas who are now Australian citizens or permanent residents and who, while they are closely involved in business activities in their country of adoption, nevertheless retain close government and business connections in their country of origin. Indeed, their implicit “foreignness” devolves from the fact that they may hold citizenship (or permanent residence status) in Australia and in another country.

“Chinese” political donations – and “Chinese” donors and companies – carry even deeper ambiguity, with at least five different meanings:

- People of Chinese ancestry, regardless of their country of origin and whether they are permanent residents or citizens of Australia.

- People who were born in the People’s Republic of China, or PRC, regardless of whether they are permanent residents or citizens of Australia.

- People who have continuing connections with the PRC.

- People who have links with the Communist Party of China in the sense of having an association with officials of the party or holding a continuing appointment in a PRC government entity.

- A subset of 4, people who act as agents for the Communist Party of China.

All these meanings have been used in media reports of “Chinese” political donations, without careful distinctions being made. Take, for example, donations from Minshen Zhu, who migrated to Australia from the PRC and operates an Australian-based business (meanings 1 and 2). He is also a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (meanings 3 and 4). In many cases, without any further evidence, these meanings of “Chinese” can then slip seamlessly to meaning 5.

The what connects to the why. A large part of the concern about overseas-based donors or foreign-sourced donations relates to compliance: enforcing Australia’s electoral laws overseas is all but impossible. And these donations make up a small but not insignificant portion of total political donations in Australia – and appear to be growing.

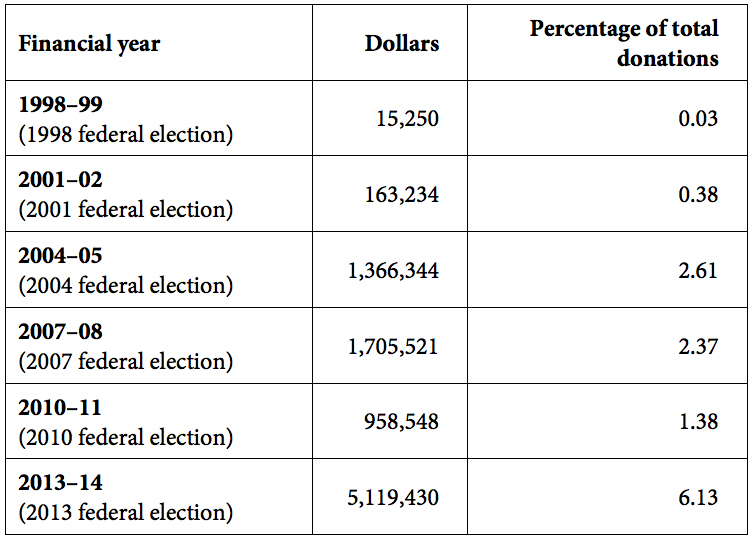

That much is evident from our analysis of the foreign-sourced donations made to political parties from 1998–99 to 2014–15. (Returns for 2015–16, which relate to funding for the 2016 federal election, are not available till February next year.) In election years, as the table below shows, these donations have generally increased both in nominal terms and as a proportion of total donations to Australian political parties.

Foreign-sourced donations to Australian political parties, 1998–99 to 2014–15

Sources: Australian Electoral Commission annual returns; authors’ calculations

At the 2013 federal election, foreign-sourced donations constituted more than 6 per cent of all donations (calculated using returns for the 2013–14 financial year). In the previous financial year – thanks to a large transfer of $3.6 million from Zhongfu Investment Group to the Labor Party’s Victorian branch – foreign donations were a tad under 10 per cent. The PRC and Hong Kong are the main countries of origin for these donations: in fact, over the past sixteen financial years, over 83 per cent of all foreign-sourced donations were sourced from those two places. The next biggest contributor was Britain, which accounted for just over 10 per cent of all foreign-sourced donations.

Both the major parties benefit from foreign-sourced donations, but Labor received nearly 60 per cent of the total from 1998–99 to 2014–15, with the Coalition receiving nearly 40 per cent. Of donations from China and Hong Kong, just over 68 per cent went to Labor.

The growing significance of foreign-sourced donations and the difficulties of enforcement do indeed add up to a clear and compelling case for severely restricting – if not banning – this form of political finance. That’s what Queensland has done, as has Britain in a similar way.

What the British parliament didn’t do, though, is ban “foreign” political donations in the broad sense – that is, donations from all non-citizens. Nor, for that matter, have Canada or the United States. “Permissible donors” under the UK Political Parties, Elections and Referendum Act include companies carrying out business in the United Kingdom. In Canada and the United States, permanent residents can still make political donations.

Indeed, a ban on political donations from all non-citizens would be unconstitutional in Australia. It is precisely such a ban that was struck down by the High Court in a case brought by Unions NSW. A central part of the court’s reasoning was that non-citizens residing in Australia are entitled to voice their political concerns by virtue of being subject to the laws of the land.

This points to the insular view of Australian society that seems to underlie some calls for a ban on donations from all non-citizens. By focusing exclusively on Australian citizens, proponents of a blanket ban fail to recognise the role of people who are not citizens – notably permanent residents and long-term residents on temporary visas – in our richly multicultural society. These people – including migrants from the PRC – should not be denied their legitimate role in the democratic process.

Worryingly, this blinkered understanding sometimes tips into xenophobia, and a belief that “foreigners” should have no role in our political process. More specifically, a strand of scarcely veiled Sinophobia, with old fears of the “yellow peril,” seems to run through the debate over donations from Chinese companies. This occurs quite subtly, firstly through the racialisation of donations from those of Chinese ancestry or those who were born in the PRC. Why is ancestry or country of birth presumed to be significant among “Chinese” political donors but not among others? Why wasn’t the donation from Lord Ashcroft referred to as “English” political donation? Why weren’t the donations from the Calabrian Mafia referred to as “Italian” political donations?

This racialisation trades on the dark ambiguity of the label “Chinese,” with an implication of interference by the Chinese government in Australian politics – an implication tapping into fears of a “Chinese” takeover of Australia’s energy infrastructure and agricultural industries.

Of course, the involvement of the Chinese government in Australia’s political system, economy and media (including Chinese-language media) is a real issue to be debated. But the implication that “Chinese” political donors are doing Beijing’s bidding is one that is often assumed rather than demonstrated.

Whatever degree of Sinophobia characterises the current debate, it is a major distraction from a more substantial malaise. An over-emphasis on “foreignness” (and “Chineseness”) distracts from an understanding of how the issue of “foreign” political donation highlights broader problems in how political money is (not) regulated at the federal level in Australia. The absence of caps on political donations and spending – like those introduced in New South Wales by the Election Funding, Expenditure and Disclosures Act 1981 – has allowed unsavoury fund-raising practices to thrive; and a laissez-faire culture within political parties has left systemic conflicts of interest untouched. All of which has undermined public confidence in the political process.

So how should we deal with foreign donations? Let’s ban foreign-sourced donations, as best as we are able. At the same time, let’s accept that “foreigners” who are living in Australia have a stake in the country they live in, work in, and come to belong to. More importantly, let’s reform the federal political finance laws more broadly in order to protect the integrity of Australia’s democracy. •