Tasmania and the United States aren’t compared all that often. But for Australians to understand how someone like Donald Trump could be elected US president, it might be useful to imagine what would have happened had the election been held in Tasmania.

In economic terms, Tasmania is seen by mainlanders as a basket case. For many years, it has experienced relatively little growth in jobs or output, and relatively high unemployment. Its state government is heavily subsidised by mainland taxpayers. The story is not all dark – population growth has returned, tourism is a growing industry and the economy is doing better than it was. But for young Tasmanians, finding jobs is usually easier if you cross Bass Strait.

It would be no surprise if a populist demagogue denouncing the status quo and promising sweeping changes won strong support in Tasmania. In July, populist independent Jacqui Lambie won one of the state’s Senate spots, and One Nation almost won a second.

In the ten years to August, employment in Tasmania grew by just 5.8 per cent, a third of the 17.5 per cent national rate. Yet Tasmania’s job growth over that decade was stronger than the rate recorded by the United States.

Sure, the American economy put on a net 6.6 million new jobs, compared with Tasmania’s 13,000, but that was a growth rate of just 4.5 per cent. Not only was job growth in the US over the decade less than the growth in Australia’s slowest-growing state, it was also barely half its own rate of population growth.

And across much of America, in the endless churn of jobs being created and destroyed, more well-paid jobs were being destroyed than created, and many of the new jobs were low-paid and part-time. Many, many people became worse off.

Ten of the fifty states of the union had fewer jobs for their people in August 2016 than they had ten years earlier. They included Michigan, traditional home of the American car industry, which lost a net 140,000 jobs over the decade. Ohio, another industrial powerhouse that has become the US electoral barometer, lost a net 126,000 jobs. On Tuesday, both states deserted the Democrats to vote for Donald Trump.

Of the four other states that crossed into Trump’s camp, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Iowa all had little net job growth – less than 2.5 per cent – over the entire decade. Florida did a bit better, but only marginally better than Tasmania, despite receiving more than a third of the nation’s population growth.

Even the massive New York state added just 6000 net new jobs in ten years. Its neighbour New Jersey added 500 – that’s fifty jobs a year. Texas, its population swollen by border crossers from Mexico, was the powerhouse, generating more than a quarter of all US job growth over the past decade. (Trump still won Texas on Tuesday, but with a majority only half of Mitt Romney’s in 2012.)

Wages in the US have grown significantly more slowly than in Australia over the past decade. Since the 1970s, income growth has gone overwhelmingly to the top 10 per cent. US output per head has grown only half as much as Australia’s over the decade, though our own growth has been sluggish. If many Australians are worse off now than they were, and/or fearful for their family’s economic future, what must it be like for ordinary families living in the US – let alone Europe?

Analysts who attribute Trump’s victory simply to racism, bigotry and misogyny miss the point. We assume that democracy and free markets work in the interests of all. The experience of the past forty years in the US has been the reverse. The Republicans in Congress have diligently protected the interests of the rich, while the Democrats have failed to protect the interests of ordinary workers and families. The result has been an economy that is not delivering gains for most Americans.

Trump has made himself the voice of the American rebellion, just as Nigel Farage did in Britain, Marine Le Pen in France, Beppe Grillo and his Cinque Stelle movement in Italy, Pablo Iglesias and Podemos in Spain, and so on. Some of these populist leaders are on the left, some on the right. But all of them are benefiting from a rebellion against the status quo from voters with good reason to be disaffected.

The US electoral system is first past the post, which makes it almost impossible for new parties to break through. (In Britain, with the same electoral system, UKIP won 12.7 per cent in last year’s election, but won just one of the 650 seats.) So Trump, after swapping his party registration several times, decided to use the Republican party as his vehicle for a presidential bid, ran on broad policies of isolationism, social conservatism, climate change denial, and hostility to immigration and trade agreements, harvesting the anger simmering in most parts of America over declining living standards and lack of jobs.

Of this, the Republicans in Congress share only the social conservatism and denial of climate change. Over the four years of his presidency, his nominal allies are likely to be his main enemies. Of that, more later.

Trump was helped by the Democrats. President Obama’s poor poll ratings over the past three years made it clear that this would be an election at which voters would be angry and wanting change. Yet the Democrats nominated a candidate who, gender aside, personified the status quo in politics.

The result was a salutary reminder that all leaders have a limited store of political capital. After a generation in the public eye, Hillary Clinton had used hers up – or rather, the Clinton family (like the Bush family) had depleted its stockpile. Voting is voluntary, so a candidate has to inspire supporters to turn out to vote. Hillary Clinton lost essentially because millions of potential supporters didn’t find her inspiring enough to vote for her.

At the time of writing, the (admittedly incomplete) count shows Trump with no more votes than John McCain won in 2008. But Clinton had won just over 60 million votes, compared with 69.5 million who voted for Obama that year. The Democratic establishment allowed her to stake a pre-emptive claim for its nomination, and potential rivals got out of her way, leaving only a fringe player, Bernie Sanders, to demonstrate how vulnerable a candidate she was.

Yes, it was a close-run thing. As election guru Nate Silver has pointed out, had just 1 per cent of all voters shifted their votes from Trump to Clinton, she would have held on to Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Florida, giving her a comfortable victory in the electoral college. As it was, like Al Gore in 2000, she won the popular vote, but too many of those votes simply swelled her majorities in safe states like California and New York.

The bellwether state of Ohio, which has not voted for a losing candidate since 1960, went for Trump in a landslide, as did rural Iowa. Even Minnesota, which voted Democrat despite Ronald Reagan’s sweep of every other state, almost went Trump’s way. Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania: this was not a racially inspired revolt of deplorable people, but the American rustbelt taking out its anger on those it blamed for making it a rustbelt.

The exit polls, as others have pointed out, show that the big shift to Trump was among those without college degrees – especially among those who did not finish high school – and among lower-income earners. (Sure, Clinton did have a narrow lead in the bottom two income groups, but the same voters in 2008 and 2012 gave Obama huge leads.) There was a swing of landslide dimensions to Trump in rural areas, less so in the suburbs, and hardly any swing in inner-city areas.

Comparing 2008 and 2016, the swing to the Republicans was almost entirely among men. In 2008, the exit polls showed Obama leading McCain 49–48 among male voters; in 2016, Clinton trailed Trump by 41–53. By contrast, the female vote was virtually unchanged: 56–43 for Obama, 54–42 for Clinton. That is some gender gap.

Hispanic and Asian voters stayed loyal to the Democrats; so did black voters, although less for Clinton than for Obama. But white voters, virtually the sole Republican constituency, went for Trump by a massive 37–58 margin. That was not much different from in 2012, when whites turned against Obama, but it does underline Clinton’s failure to make potential supporters feel that her candidacy was relevant to them.

The exit polls reveal two other important points. In 2008, Catholics voted 54–45 for Obama, while Protestants voted by the same split for McCain. In 2016, Protestant voters went for Trump by an extraordinary 60–37 margin, and even Catholics endorsed him by 52–45. Relative to 2008, Trump also made up ground among Jews and members of other religions (though surely not Muslims?), but those with no religion went even more strongly for Clinton (68–26) than they had in 2008 for Obama (67–31). This level of party identification with religious beliefs is something new, and troubling.

Finally, there were startling shifts in the votes of the young. In 2008, Obama had set the younger generation alight, winning 66 per cent of the votes of all voters under thirty. In 2016, Clinton failed to set them alight, winning just 56 per cent from voters aged eighteen to twenty-four, and 53 per cent from those twenty-five to twenty-nine. While voters over sixty-five voted exactly as they had in 2008, the shift of votes among the young suggests that Trump’s egotistic, hate-filled campaign appealed more to young Americans than did that of the former war hero and genuinely respected senator, John McCain. That too is worrying.

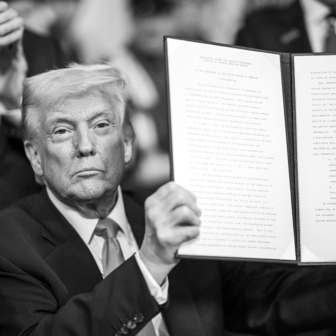

The Financial Review labelled Trump’s victory “the American Revolution.” It was wrong. This victory is the American Rebellion. It would be a revolution if Trump could perform in office what he pledged on the campaign trail. Only his true believers would expect that.

Trump’s policy directions are very different from those of the Republicans in Congress – and it’s Congress that enacts the laws. His opponents inside the party are unlikely to submit to his authority; they have been charting their own political career paths, and intend to be doing so long after Trump has left the building. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell’s frigid response to Trump’s call for massive new infrastructure spending was the first of what will be many clashes of heads.

Lost beneath the presidential campaign, Tuesday’s voting saw the Democrats pick up two Senate seats from the Republicans, reducing their majority from 54–46 to 52–48. Given that the Senate requires a majority of at least sixty votes to end a filibuster – a tactic by which opponents of a bill prolong debate endlessly to prevent its passing – President Trump will find it difficult at best to pass legislation without Democrat support.

On the campaign trail, Trump could promise anything. In the Oval Office, he will be able to implement some of those things, but only some. The gap between expectations and delivery will be large.

The Republicans will now control the White House and both sides of Congress. If anything goes wrong, if there are disappointments under President Trump’s watch, one side will get the blame. This will be an ugly but fascinating four years. •