NSW premier Mike Baird claims he has a mandate to implement his electricity privatisation plan. And he’s right. Baird has been saying for months that his government, if re-elected, would lease 49 per cent of the state’s “poles and wires,” and a big majority of the NSW electorate voted for his Coalition parties.

But that doesn’t mean Baird convinced voters that electricity privatisation is a good idea and that they’re now in favour. A referendum on the issue would still surely fail. His government was re-elected despite this unpopular policy.

Does this mean that Baird’s victory would have been even bigger if he hadn’t included privatisation in his re-election manifesto? That’s a tricky one, because Baird’s public devotion to the cause as state treasurer means a hand-on-heart “never ever” promise might not have been believed. A Labor campaign about a “secret agenda to privatise” might have developed traction, and that would have been worse for the government politically. It was presumably a factor in the government’s decision to come clean.

There’s a tendency for political analysts to assume that because an issue provokes a strong, even emotional, reaction in the community, and dominates the media coverage, it’s an important driver in people’s decisions at the ballot box. But there are many things people feel forcefully about that don’t affect their votes.

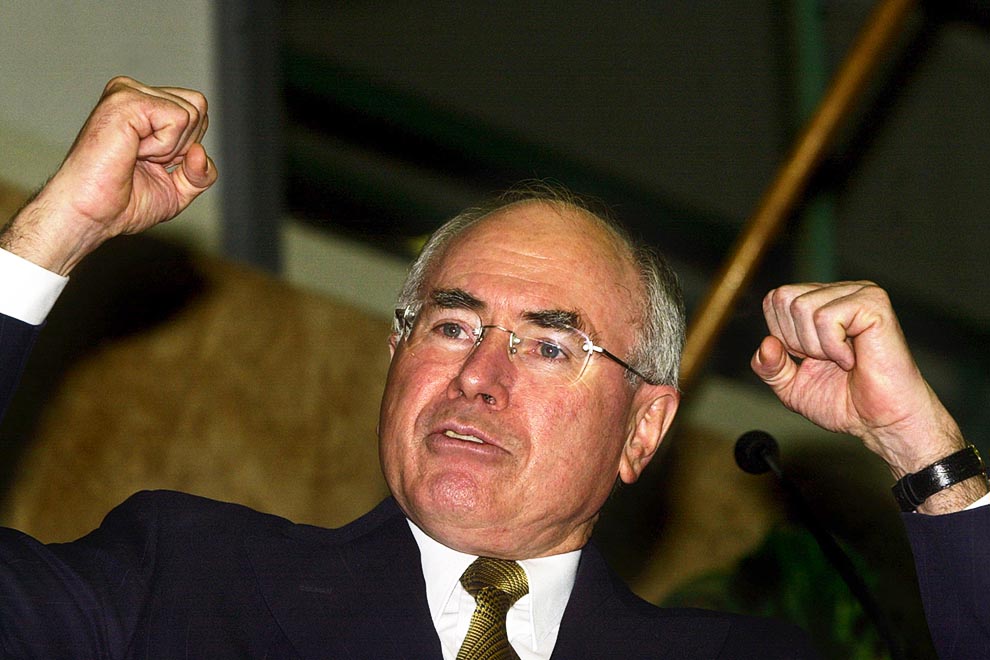

Three recent federal results have achieved “single issue” status in the collective memory. The Howard government’s 2007 loss is popularly blamed on WorkChoices. Its earlier 2001 re-election is widely believed to have been driven by asylum seekers. And Paul Keating’s unexpected victory twenty-two years ago came from his opponent’s promise to introduce a GST.

It’s likely only the last-named deserves the honour. We can say with reasonable certainty that had opposition leader John Hewson promised not to do anything much at all in 1993, as John Howard did three years later, he would have become prime minister.

Hewson has suggested that he’s responsible for the subsequent “small target” template so favoured by Australian federal oppositions, and he has a point. Labor’s 2007 campaign provides a textbook example (Kevin Rudd’s “me too” became a tagline) and in that case the result was what 1993’s should have been: a cyclical change of government, a party ebbing out of office after four terms once the opposition had reassured voters that it wouldn’t go crazy if it were elected.

And what of 2001, when the Howard government achieved an apparently unlikely re-election after whipping up hysteria about boat arrivals? Early that year the Coalition appeared gone for all money, trailing by double-digits in the opinion polls. But it was already clawing back when the Tampa arrived in late August. That event, and the turmoil and emotion accompanying it, and then the September 11 attacks in the United States lit up the radio talkback lines and produced some very big poll leads, again double-digit. But on election day in November the win was a modest 51 to 49 per cent after preferences.

And if you trace the opinion poll trajectory from early 2001 to mid August, and extrapolate that line to November, you end up at around the election result anyway. The Howard government was probably headed for re-election regardless.

Yet politicians, their advisers and the media still cling to the supposed lessons of 2001; they pollute Australian politics, uniquely among Western nations, to this day.

In 1998 Howard was re-elected despite lumbering himself with a GST. As with Baird and electricity privatisation, it would be preposterous to conclude that he “sold” the package, or convinced Australians of its desirability. The GST was disliked right through to election day and beyond. The Coalition recorded the lowest winning two-party-preferred vote in federal history.

But just as we can be reasonably sure of the GST’s overall impact in 1993, it also probably made 1998 a real competition. With no GST, re-election would likely have been easier.

The GST went on to become an emblem of the Coalition’s economic competence and Howard’s “conviction politics.” It assisted him politically in his last two terms. He dines on it to this day.

The tax has been accepted as part of the fabric, and can’t be introduced again, but the ghost of that tight election hovers as well. Any suggestion of an increase or broadening raises a warning flag, and not just from Labor: in 2004, and again in 2007, treasurer Peter Costello cautioned direly that wall-to-wall state Labor governments, combined with federal Labor, might bring a GST rise. Which naturally drove those opposition leaders to swear they would never do that.

And in the first leaders’ debate of the 2013 election Kevin Rudd whined and carped that an Abbott government would increase the GST rate, which naturally led Tony Abbott to assure the country it would not.

Have a quick squiz across the ditch. Before New Zealand’s 2008 election, opposition leader John Key insisted he would not touch the GST. He and his party won office and, midway through their term, increased it. He was comfortably re-elected. New Zealand has neither states nor an upper house, which made the change much easier than it would be here.

Howard’s GST and Baird’s poles and wires were exceptions. In Australia, reforms are usually sprung on the voters, having gone unmentioned, or perhaps been vigorously denied, at the previous election. They meet resistance but once they’ve been introduced people usually get used to them. Most of the headline changes over the last half a century that are now seen positively – ending White Australia, increasing immigration from the late 1970s, accepting Vietnamese refugees, dismantling tariffs, and all those “reforms” of the now celebrated Hawke–Keating agenda – fit that category.

In modern, “professionalised” Australian politics, parties’ first strategic port of call is to ramp up fear, on as many fronts as possible, about what their opponents might do. The modern media – attention-span deprived, story-churning – joins in, demanding answers, and political leaders, the memory of Hewson hovering, swear off anything vaguely contentious. If in doubt, rule it out, we’ll do it anyway once we’re in office. New governments break pledges – that’s always happened – but the number and extent has escalated.

A wise person once said that Australians are easily terrified by the prospect of change and then adapt to it with relative ease. But the current federal government is stuck in political hell, with unpalatable policies in suspended animation, forever in prospect but never becoming reality.

That’s partly because of a large Senate crossbench, a function of decreasing support for both major parties. But it’s also because the Coalition unequivocally ruled out so much of its agenda before the 2013 election, leaving it with little moral authority to argue its case.

Perhaps the “politics is broken” crowd have a point.

Mike Baird’s victory is being popularly transcribed as a case of a courageous politician taking a difficult agenda to the voters and being duly rewarded. Although it’s more complicated than that, if this encourages other politicians to be upfront before elections, it would be a good thing. But it’s difficult to see the major parties’ armies of advisers, pollsters and strategists allowing that to happen. •