Most Sydneysiders and millions of tourists know The Rocks as a historic precinct in which it is possible to have a good night out while enjoying the ambience of a genuine nineteenth-century townscape replete with historic pubs, tiny workers’ cottages, handsome terraces, inviting eateries, pocket parks and cobbled laneways – all within a stone’s throw of the harbour and the CBD.

Some are vaguely aware that the area has been the site of European activity since that day in January 1788 when white men from a distant land came ashore from their strange sailing ships and – in their strange uniforms – claimed possession of the land in the name of a faraway king. An educated few would know that for thousands of years before these invaders raised their flag the area had been home to the Cadigal people, members of the Eora clan.

Even fewer remember from their history lessons that while these newcomers were busy establishing the infant colony, a new constitution was being forged in the United States, France was facing a revolution, and King George, back in the mother country, would go insane. Such, in part, was the antipodean political context at the time of “first” settlement in Australia.

In Sydney Town, the immediate job for government was to establish a peaceful colonial township while keeping the convicts under control. The Rocks area on the western side of Sydney Cove was an obvious place to gain a foothold for the invasion that commenced in January 1788, and to lay the first bricks in what was a nation-building enterprise.

A little under 200 years later, in 1973, The Rocks was far from peaceful. The events there, early on a cold morning late in October, would become famous in the annals of the Australian urban conservation movement.

An old building in Playfair Street was the focus of the action. Despite a green ban by the Builders Labourers Federation, or BLF, on demolitions in the wider Rocks area, non-union labour had commenced pulling down the building. A passive occupation of the site was seen as a way of furthering the conservation cause and ensuring that the green ban held. But under instructions from the state government and premier Askin, a large force of police arrived shortly after dawn to ensure that the non-union workforce could continue the demolition.

The police found the site occupied and barricaded by a very resolute group of locals and the two BLF leaders, Jack Mundey and Joe Owens. The police arrested fifty-eight of the activists, Mundey and Owens included. As Mundey recalls:

That morning’s occupation was just one of the large number of separate actions that, together, saved The Rocks. The combined power of citizens and unionists stopped insensitive development and, more importantly, gave citizens a say in the making of decisions.

Why was Mundey arrested? A strictly legal answer might be because he defied a police order to move on, to cease his trespass. A more realistic response might be that the premier wanted his head.

Why did residents defy the police? Because they were facing summary eviction from their homes, the destruction of a tight-knit community, the wrecking of a familiar and much-loved landscape, and bureaucracy’s failure to properly consult and negotiate.

Why did the whole Rocks saga become front-page news – eventually entering the history books as a brown sequel to the earlier and greener Battle for Kelly’s Bush? Because it involved the mass refusal by an army of determined unionists to apply their labour to an unpopular development proposal, and because it was a catalyst, a unifying event, an extraordinary and unprecedented moment for public sentiment to emerge as a driving force for reform of outdated planning laws and the introduction of heritage conservation as a proper responsibility of government.

The story begins with an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900. This threat gave the state government a convenient excuse to compulsorily acquire most of the area in order to achieve two pressing objectives. The first was to bring this sector of the harbour waterfront into public ownership so that progressive modernisation of wharfage could take place. The second was to secure control of a site that would be a strategic element in the construction of a bridge across the harbour to the north shore.

From that date forward, residents became tenants of the state. Little private ownership remained, and private investment virtually ceased. In the 1930s a government committee recommended that this “slum” be cleared to make way for flats, offices and commerce. In the event, nothing of the kind happened, but the massive construction program for the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1928 to 1932) took a partial toll. The building of the Cahill Expressway across Circular Quay in the 1950s also had its impact on the community, both socially and environmentally.

By and large, though, this traditional inner-city working-class community – many of whose members traced their lineage back to colonial days – was able to stand its ground. Then, in 1960, the state government under Labor premier Robert Heffron invited selected developer teams to submit fresh proposals for reshaping the area east of the expressway, right down to the harbour’s edge. Once again, big changes were looming.

In January 1964, the construction firm of James Wallace Pty Ltd was named the successful tenderer on the basis of a scheme prepared by leading Sydney architects Edwards Madigan & Torzillo. From the harbourside at Dawes Point as far south as the Cahill Expressway, the old Rocks would be replaced by high-rise office towers, retail and commercial space, and some thirteen residential apartment blocks linked by a continuous traffic-free podium element at ground level.

After a conservative state government was elected in May 1965, the scheme was shelved. But the building boom in Sydney was moving into top gear and a year later the prospect of wholesale redevelopment again appeared when Liberal premier Askin sought the advice of John Overall, the head of Canberra’s National Capital Development Commission. On the ground, little had changed. The Askin government saw a large, rundown yet extremely valuable area of public land occupying a prime harbourside position on the edge of the CBD.

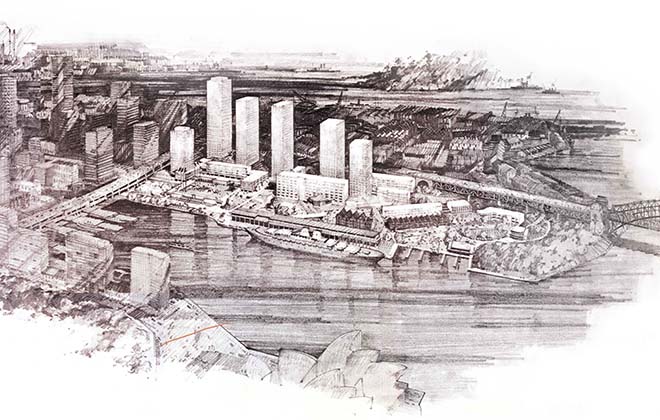

The trigger: Artist’s aerial view of 1967 scheme for The Rocks. Courtesy Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

Yes, it was occupied, but only by a handful of low-income state tenants, slum-dwellers, hippies, down-and-outers and families on the welfare housing list paying ridiculously low rents. The government’s position was clear: in the name of progress they would have to go. Under Overall, the project’s ambit was extended south. As with the abandoned Wallace scheme, the government’s ultimate objective was to enable the huge real-estate potential of the area to be unlocked and exploited to the full.

Overall presented his Observations on Redevelopment of the Western Side of Sydney Cove Rocks Area to Grosvenor Street to the NSW parliament in June 1967. At his recommendation, the study area had been extended to include “the contiguous Crown-occupied land in West Rocks and Dawes Point. Observatory Hill, Argyle Place… [and] other holdings extending from Dawes Point to the Quay.” As Overall wrote in his 1993 memoir, his assignment was:

a concentrated exercise… proposing the development of the whole area around a design theme. Its aim was to retain the historic parts… opening up of Sydney’s majestic waterfront by developing a great harbour-front square that would provide the city with a memorial for its birthplace.

The National Trust resolved to support the scheme and its proposal to preserve “about seven buildings.” The government adopted Overall’s scheme and embraced with enthusiasm his recommendation that a special redevelopment authority be established to implement it. As later events proved, that single recommendation triggered the chain of events that led to blood in the streets, lockouts of building sites, police arrests, massive street demonstrations and, eventually, the famous BLF green ban of 1971–73.

John Overall was an architect, ex-military commander, and very capable public servant – attributes he brought to his Rocks assignment in full measure. In particular, his architectural training and his ready access to the considerable design resources of the National Capital Development Commission coloured his approach to urban design.

This background was a major influence on the beaux arts formality – some might call it sterility – of his recommended scheme, with its grand plaza overlooking Circular Quay, its axial building relationships, and its serried rank of towers stepping down to the harbour’s edge. In hindsight it could reasonably be seen as the offspring of the dry, sterile urban design achievements of his commission in central Canberra. Its general spirit was vaguely reminiscent of the postwar plans for the blitzed St Paul’s precinct in London prepared by Sir William (later Lord) Holford, one of those eminent UK-trained designers whose advice was regularly sought by the federal government in Canberra during the three decades following the end of the second world war.

Overall’s military background also gave him the no-nonsense management skills to get things done. He was comfortable in the company of government ministers and captains of industry. Socially, he was suave and likeable, with a twinkle in the eye, always impeccably dressed. These attributes endeared him to his political masters, and he remained comfortably in Canberra’s top job for fourteen years.

Overall’s recommendation that the state government create a dedicated agency to undertake the redevelopment of The Rocks was hardly a surprise, given that his own National Capital Development Commission had proven to be the perfect model for a major city building project. Largely autonomous in its relationships with other federal agencies, and enjoying a mandate to get the job done as expeditiously as possible, the commission had a dream run as both a design agency and a construction authority. Almost overnight, the empty paddocks of the capital territory were filled with houses, roads, parklands, schools, neighbourhood centres and civic facilities of all kinds. The commission attracted skilled professionals in architecture, landscape design and civil engineering, and it enjoyed the certainty of continuous federal funding.

The state government’s decision to create a special authority was shortly followed by the impetuous passing in January of the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Act 1968. Public debate on the bill was not on the agenda and press coverage was minimal. Two years later, in January 1970, the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority, or SCRA, was established. The authority’s first executive director and deputy chair was Owen Magee, another ex-military man whose field rank as a recently retired brigadier was prominently and proudly noted on the back cover of his 2005 memoir. Obviously a no-nonsense operator, there could be no better man for the job.

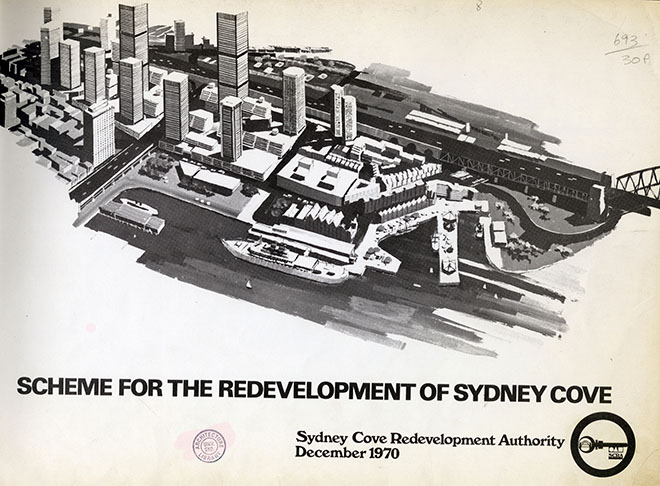

Under Magee, the SCRA quickly appointed a consortium of consultants led by Melbourne architects Bates Smart & McCutcheon, with a brief to review the Overall scheme and present a detailed set of proposals to the government within a year. In December 1970 they delivered, and their scheme was promptly adopted. The SCRA was in business.

In retrospect, it must be seen as an extraordinary miscarriage of the democratic process that, in preparing all three schemes for this unique area, not even lip service was paid to the concept of citizen participation. In the case of the Overall scheme, coming at a time when participation was entering the lexicon of contemporary planning, neither Overall nor his client saw any need to consult with the large resident community in the area or with the people of Sydney generally.

Here was a mature community with a long memory and longstanding associations with an area it had come to love. In the case of the SCRA scheme and its Melbourne-based architects, the tight schedule set by the government virtually ruled out any serious consultation. For this high-powered consortium, the prospect of community participation would have been dismissed as an expensive and time-consuming diversion. Weren’t the majority of residents low-income public housing tenants, indeed slum-dwellers? What right did they have to influence or interfere with a multimillion-dollar urban renewal project designed to clean up, once and for all, this crumbling and ramshackle quarter that was disfiguring the site of the nation’s birthplace?

Owen Magee provides a highly personal account of this prestigious state project in his memoir, How the Rocks Was Won. His choice of title says something about his (and the authority’s) philosophical position on the controversy that unfolded as he took the reins back in 1970. For this ex-military field officer and his newly created SCRA, the aim was to “win” the battle and eventually end the union’s “rule by violence,” as described in his second chapter. He makes it clear in his preface that his purpose in writing the book was to ensure that “the true story of how The Rocks was revitalised” was “set straight” in order to counter “the myths, first fabricated by the BLF and their supporters and repeated so often since that their truth is now seldom challenged.”

Magee’s take on the matter of consultation was clear. For him, consultation meant talking, negotiating and bargaining with the relevant bureaucracies, and the thought of entering into civilised discussions with the residents or interested community-based organisations would have been remote from his military mind.

Quite reasonably, he saw “the establishment of close contact at working level with the organisations controlling Sydney’s essential services and development” as being vital to the authority’s planning program. Some twenty-four “public and private” organisations were brought into the process, including agencies responsible for roads, planning, water, public works and public housing. His list diplomatically included the Sydney City Council and the National Trust, although the former had no real power in the area and the latter was considered to have no teeth. But talking to the people at grassroots level was not his style. His book is vague as to his views on citizen participation as a concept, and the topic does not appear in his index.

In later dealings, it’s clear that there was no love lost between Magee (and presumably the authority) and the Rocks Resident Action Group, professional institutes (including the Royal Australian Planning Institute and the Royal Australian Institute of Architects) and the BLF. Magee’s colourful language in his chapter on the “Riots in the Rocks” makes it abundantly clear that for him at least, the unionists were “thugs,” “a mob” of “screaming rioters” and “conspirators,” “drunkards,” and members of a “power-mad” union intent on “rule by violence.” BLF leaders Bob Pringle and Jack Mundey were “henchmen,” promoting the “power of the proletariat” and their “ruthless” desire for “worker control.” The NSW parliament had given the SCRA unprecedented powers at a time when town planning legislation was primitive, when there was no statutory protection for heritage, and when a right-wing conservative government was in no mood to have its plans derailed by resident activists, left-wing unionists, or their misguided allies in the design professions.

There may also have been a disinclination to deal with – or even a directive to avoid – those local design professionals. For reasons unknown, Magee’s book ignores the two professional bodies, despite the evidence that the planning and architects’ institutes had significant concerns about the 1970 scheme and both institutes made formal submissions to the authority setting out those concerns. Both bodies also achieved something that eluded the authority at the time: the development of a mutually respectful working relationship with Jack Mundey and other BLF leaders as well as with the residents’ action group. In the case of the planning institute, a policy statement released in June 1972 called for the state government to amend the SCRA Act “to provide for better consultation, public participation, and occasions for the exhibition and seeking of public comment on the policies and proposals of the Authority.”

If participation and consultation with the non-government sector was a low priority for the SCRA, its highly selective approach to heritage was at least explicit. Magee quotes from the minutes of the authority’s inaugural meeting on 20 January 1970, when its chair, William Pettingell, announced that the task facing the new organisation was one “which would not only preserve the historical significance of the area [but] would also see that it ran a useful business enterprise for the government and the people of the state.” Magee later states that one of the key requirements outlined to the incoming consultant team was that historic buildings worthy of preservation should be incorporated in the new development. “Worthiness” was not defined and, not surprisingly, very few buildings were found to be worthy.

In hindsight it can reasonably be claimed that much of the ensuing furore over the heritage issue was the result of disputes about the interpretation of that mandate. On the one hand was the planning institute’s view that the project site should be designated as a single coherent and unified conservation zone, with only selective redevelopment of certain properties within a heritage context. On the other was the view – first advocated by John Overall and later adopted by the authority – that apart from a small number of distinctive “historic buildings” the bulk of the site was ripe for demolition and redevelopment to satisfy the pressing commercial imperatives laid down by the government.

On the heritage issue, the National Trust’s position was evolving, if not ambivalent. At the invitation of the authority in 1970, the Trust submitted a survey and report, adopted by the National Trust Council in September that year, listing twenty-three buildings or groups of buildings “with first, second and third priorities for preservation, and a statement of townscape principles.” According to a file note from the Trust’s acting director, John Morris, many of the buildings that the organisation had recommended for preservation were included in the authority’s scheme, published in February 1971. The Trust duly expressed its support for the authority’s position, although only five buildings in the entire Rocks area had been formally entered onto the Trust’s register.

Subsequently, the Trust moved to correct this anomaly by directing its Historic Buildings Committee to review the listings, “taking into account what the committee believed to be essential to the character of The Rocks. That is, groups of buildings and the spaces they contain, together with the very important framed vistas which these spaces permit.” Significantly, the committee decided to recommend the inclusion of a number of twentieth-century buildings that had been overlooked until then. In April 1974 the Trust considered a schedule of new and revised listings, thereby preparing for its later classification of the entire Rocks precinct as an urban conservation area.

The SCRA scheme was founded on the expectation that it would be a model – a demonstration – of what could be achieved when the crème de la crème of the country’s design consultants, project managers, land economists, traffic engineers and real estate brains were brought together to determine a profitable future for this very valuable piece of publicly owned property.

Magee and architect Walter Bunning visited overseas precedents such as La Défense in Paris and the Barbican scheme in London during a whirlwind study tour after Magee’s appointment as executive director. The resulting design was a cluster of brutalist tower blocks stepping down the ridge to the harbour’s edge and ranging in height from thirty to fifty storeys, accommodating offices, retail uses, luxury hotels and apartments. A labyrinthine system of underground car parks made sure that motorists would not be inconvenienced. The heritage lobby was placated by the retention (or relocation) of a handful of historic buildings, mainly in the northern sector.

Clear, demolish and rebuild: the 1970 scheme for The Rocks, as adopted by NSW government. Courtesy Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

The government summarily adopted the scheme after a token public exhibition, and its implementation was promptly authorised in December 1970. The authority probably saw the holiday period as an auspicious time to release such a potentially controversial scheme. In February the plans were officially launched, and briefly put on public display.

Over the next few months the SCRA considered the vexing matter of ensuring that rental tenancies were terminated so that demolition for the first stage of the redevelopment could begin. The authority also commenced its program of renovation and conservation of a handful of historic buildings that were now part of its portfolio. Rumours of impending evictions and loss of tenant rights, such as they were, led swiftly to the formation of The Rocks Resident Action Group. Their leader was Nita McRae, third-generation Rocks resident and mother. In November 1971 the group approached BLF secretary Jack Mundey and president Bob Pringle seeking union help. A green ban was placed, and the battle for The Rocks was about to get under way.

At the time, according to Mundey, “everyone should be interested when Sydney’s history and beauty is going to be torn down, and when people in the way of this so-called progress are regarded as minor inconveniences.” The “people” in this case were the residents facing eviction. Other people (not mentioned by Mundey) were the officials in charge of the redevelopment, and the financiers, developers and builders whose interests were of a more material nature. These “others” included anyone on the right who saw the BLF’s decisive intervention as a threat to the state’s economy, led by a group of communist extremists intent on defying the rule of law and on undermining the integrity of the Master Builders Association as the influential peak body within the NSW building industry.

From the outset, the campaign to save The Rocks had to be a fundamentally different battle from that which was still raging at Kelly’s Bush. In the latter case, it was the future of rare harbourside bushland that was at stake. In The Rocks, the welfare and housing needs of hundreds of low-income public housing tenants were among the primary drivers. Loss of heritage and history was another. As for the wider public – and a growing cohort of concerned professionals, civic leaders, “ordinary folk” – there was a palpable feeling of outrage at the cavalier way a state government could comfortably accept these architecturally audacious schemes without any attempt to assess public opinion.

Almost half a century on, the contemporary observer familiar with the human scale and undeniable charm of this mid-Victorian townscape could be excused for failing to understand what was being proposed at the time. The archives say it all. Many historic properties from Grosvenor Street north towards the harbour were to be razed and replaced by massive tower blocks, concrete plazas, podiums. Modern architecture was to be given free rein in this special place – all in the name of slum clearance and “urban renewal.”

Unlike Kelly’s Bush, where the locals were dealing with a private developer, the opponents of the scheme for The Rocks were facing a powerful statutory authority with a mandate to clear, demolish and rebuild. There was no local council directly involved, because the role of a local authority (the Sydney City Council) had been usurped by the state government through the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Act. In The Rocks, there were no green issues as such; but there was what many came to see as the most important question of all for the birthplace of European Australia: was it not vital that this historic precinct be protected and conserved for posterity as an indispensable part of what later came to be known as the National Estate?

In simple terms, the BLF’s green ban led by Mundey and Pringle proved to be the kiss of death for the official SCRA scheme that had been so enthusiastically adopted by the Askin government. The ban provided a breathing space for residents and supporters from outside to consider their options. It encouraged the area’s community to work with a group of interested professionals in the preparation of a people’s plan for their historic turf, a project that came to nought in bricks-and-mortar terms but would indirectly influence the review of the SCRA scheme, which eventually, and perhaps reluctantly, was commissioned in 1974.

The revised SCRA scheme signalled a significant volte-face for the authority. From that time on there would be no going back to wall-to-wall high-rise office towers, luxury housing for the fortunate few, and tokenistic nods in the direction of the heritage lobby. Indeed, Magee’s book includes a detailed schedule of domestic, commercial and civic heritage restoration projects that were successfully undertaken between 1970 and 1985 – an impressive list by any standards. From 1974 onward – at least until well into the 1980s – the work of the authority took it into new fields in which consultation with residents would take place as a matter of course on controversial matters. Conservation became a priority rather than a soft option. The resident population would be increased, with a reduction in office and commercial accommodation, and there would be an explicit commitment to low-to-medium building heights in the historic core area. North of the Cahill Expressway, high-rise was out.

In more recent years, the authority’s conservation effort has included some meticulous archaeological work that has added greatly to the fund of knowledge about the routines and lifestyles of the intrepid lads and lassies who found safe haven on this rocky hillside during the boisterous colonial era and the decades after. And the area’s role as a setting for public art has seen the installation of a larger-than-life, three-dimensional portrait of Jack Mundey in Globe Street, one of the oldest laneways in the old Rocks.

In 1995 the SCRA quietly dropped the word “redevelopment” from its official title – tacit recognition that heritage conservation was not only culturally important, but also officially legitimate, as well as commercially attractive. As locals and tourists flocked to visit and spend, the cash began to flow. A further change came in 1999 when the newly constituted Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority took over responsibility for the area. A couple of years later, this custodial role for state-owned harbour properties was augmented by an unexpected initiative of the federal government, when it established the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, a new federal agency whose task was the preservation and rehabilitation of eight Commonwealth-owned properties around the harbour.

The entry of the federal government into the Sydney Harbour management scene was the culmination of a vigorous five-year-long grassroots campaign involving activists from harbourside communities, strongly supported by the National Trust. In December 1997, the Trust’s president, Barry O’Keefe, wrote to members urging their involvement and inviting them in turn to write to their local federal member of parliament, including Tony Abbott, the Member for Warringah. The following year, a press release from the Trust’s executive director welcomed prime minister John Howard’s “entry into the debate” about the future of the Commonwealth lands. The Trust’s priorities were clear: recognition of the “immense conservation values” of the remaining harbourside bushland, identification and recognition of the many items of built heritage, retention of public ownership of the lands in perpetuity, and the allocation of adequate funds to ensure effective conservation and management.

Nearly half a century later, The Rocks is the destination of millions of locals and visitors who come to the area to enjoy its ambience, thriving night life, handsome Georgian townscapes, cobbled alleyways, churches, open spaces, and many reminders of an earlier Sydney. But this is not to say that the entire Rocks–Millers Point precinct is in good condition. Poor maintenance and neglect by successive state governments raise questions on the future of certain parts of this heritage area, while the process of selling heritage houses to the private sector has already commenced.

It is probably this wilful “death by a thousand cuts” policy of neglect that triggered Miranda Devine’s trenchantly scornful description of Millers Point on 26 March 2014. She claimed in her Daily Telegraph column that “Millers Point, from the northern end of Lower Fort Street through Argyle Place to Merriman Street in the west and down to the southern end of High Street, is a decaying monument… a rundown hovel [sic].” To the uninitiated, this might seem to be reasonable enough. But when she goes on to describe this neglected place as “a decaying monument to the stand over tactics of the wharfies and the defunct, deregistered and disgraced BLF… a reminder of this city’s bad old days of greed, thuggery – and graft for those in the know” she might be accused of overstepping the mark. If decay and neglect are evident today, it is not because of the BLF; it is the result of three decades of poor maintenance by a negligent state government. Curiously, Devine’s unproven accusations of “greed,” “thuggery” and “graft” during the period of the BLF’s intervention can be compared to her silence on the rampant corruption with which the Askin government was associated at the time of the green bans.

To close the circle, the chair of the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority opened Jack Mundey Place in The Rocks on 1 May 2009. Within a stone’s throw of the setting for the bulldozer charges, bashings, sit-ins, lockouts and arrests of the early 1970s, Mike Collins named a small piece of the city after the man who began the conservation process during that turbulent period:

All movements need leadership, and this one found a dynamic and charismatic leader in Jack Mundey. He was the right leader at the right time… the movement that he led here at The Rocks was the genesis of Green Bans, and part of rethinking of planning and heritage in New South Wales… there is therefore a direct lineage between the protests that Jack led here and the birth of regulated heritage preservation around Australia… Jack Mundey Place celebrates this important moment in our history [emphasis added].

Coincidentally, the naming of Jack Mundey Place occurred at the same time as the release of a Revised Heritage Policy by the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority. This document is evidence enough of the steady reversal of government policy for this area during the period separating the SCRA–Magee era and the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority under Mike Collins. The revised policy is realistic in its acknowledgement that change must be accommodated if The Rocks is to continue “as a real place rather than as an artificial tourist destination… it is insufficient to expect that recognition of heritage values alone will conserve the place.” It follows that management of the area must involve adaptation – “provided that the uses and physical changes which result are compatible with the heritage significance of individual places and their settings.”

Given the irrefutable evidence of such a profound shift between the philosophical positions in 1971 and today, it could reasonably be concluded that the efforts of Mundey, the BLF and the heritage lobby of the 1970s have been well and truly vindicated. •

This is an edited extract from Jim Colman’s new book, The House That Jack Built: Jack Mundey, Green Bans Hero, published by NewSouth.