Some commentators are telling us the budget shows the Abbott government has abandoned efforts to get the budget quickly back to surplus. They’re wrong; it abandoned that priority soon after it took office. This budget takes us further away from it, but that’s not the point.

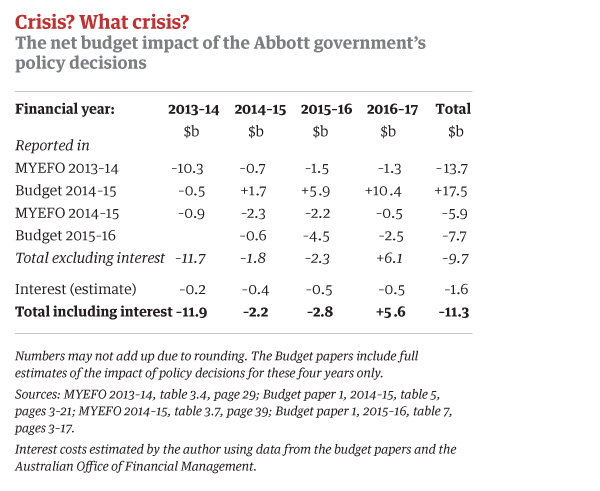

The fact is that even at the end of last year, the budget papers themselves estimated that in the four financial years covered in this term of office, the net impact of the Abbott government’s policy decisions had been to add a net $2.1 billion to the budget deficits it had pledged to reduce.

Tuesday’s budget added another $7.65 billion of net new spending over that period. Treasurer Joe Hockey told us that all his new spending would be paid for by savings, but like so many things Joe says these days, that turns out to be simply not true. His own budget papers now estimate that the government has added a net $9.7 billion to the cumulative budget deficits for those four years.

Even that figure rests on a charming assumption that you can borrow more money without having to pay more interest on it. Times have never been better for governments to borrow money, but we’ve not reached that point yet. Back in the real world, I estimate that the additional debt implies an extra $1.6 billion of interest bills over the four years.

Had the government simply left Labor’s policies unchanged for these four years, the budget papers imply, we would have run up cumulative deficits of $137.7 billion. Instead, the Coalition’s efforts to fix the budget have resulted in cumulative deficits of $149 billion.

This was not something that started this week. It started in the government’s early days, when it handed the Reserve Bank an unsolicited gift of $8.8 billion, essentially because it wanted to run a political narrative that would contrast a big bad Labor deficit in 2013–14 with its own smaller deficits thereafter.

It was a big deficit in 2013–14: $48.5 billion. But the budget papers imply that $11.9 billion of that was added by the Abbott government’s own policy decisions. Labor’s contribution was just $36.6 billion.

The government’s hopeful estimate is that next year’s budget deficit will be $35.1 billion; on current assumptions about iron ore prices and so on, Labor’s policies would have given us a deficit of $32.3 billion.

It is a different story from 2016–17 on. The government’s big cuts to foreign aid, and its plan to shift much of its health and education budget to the states, will eventually help the budget back into surplus – by 2020, on optimistic growth assumptions, or sometime later. But the budget papers work on four-year estimates, which make it impossible to measure the net impact of the government’s decisions after 2016–17.

What has really changed with this budget? Essentially, in 2013–14 the Abbott government was in its revolutionary phase, reallocating taxpayer resources to favour its own interest groups. It scrapped the mining and carbon taxes, as urged by its business allies. It made the most vulnerable bear the brunt of budget savings: the poor of Africa and eastern Indonesia, through its foreign aid cuts, and the young unemployed and sole parent families, through its cuts to welfare. It appointed its mates to government posts; the Bjorn Lomborg farce is a hangover from that initial phase.

That went down badly with the voters, so the government changed course. It now wants to be seen as a normal government – and so, to our surprise, it has produced a normal budget. It’s transparently political in purpose but, I would argue, it is economically responsible.

But it’s economically responsible in a way totally different from how the Coalition has cast the debate until now. As other commentators have remarked, it is very reminiscent of Wayne Swan’s budgets. With two or three startling exceptions, there’s not much exciting stuff. There is some useful tinkering to better target a few spending programs or plug holes in the tax system. There is a constant search for savings, especially where they will have little electoral impact.

And there is the same reliance that Swannie’s budgets had on optimistic assumptions of robust growth in the economy and strong tax collections that will restore a surplus before long… well, at least by 2020.

This budget certainly does nothing for deficit reduction, adding $10.1 billion of new spending over the next four years but raising just $0.8 billion in new revenue. And even that would largely be taken from foreigners: the “administrative fee” on foreign home buyers, the tough new tax regime on working holiday-makers, and another hike in the cost of Australian visas. What do they all have in common? Those affected don’t vote here.

Mostly, as the government tries to reoccupy the political middle ground, the budget seeks to bury the unpopular measures the Senate refused to pass last year. Instead of wanting to make young people wait six months for unemployment benefits, it now wants to make them wait four weeks. Last year’s plan to index pensions to the CPI is gone, and the plan to force mothers off Family Tax Benefit B once their youngest child turns six is now just a bargaining chip that the government plans to discard if it can negotiate its revised welfare reforms through the Senate.

Some holdouts remain, however, such as the proposed freeze on family payments and eligibility thresholds, which the government wants the Senate to pass in return for its more generous childcare payments. And defying his own orders to present a calm, normal image, it appears that the prime minister has used the budget to pick a fight with the Victorian government – or in effect, with almost six million Victorians – by giving the state only a trickle of transport funding and demanding that it repay the Commonwealth’s $1.5 billion contribution to the now-abandoned East-West Link road tunnel.

In 2015–16, the budget papers reveal, the Abbott government plans to invest $1625 million in key transport projects in New South Wales, $1200 million in Queensland and $1015 million in Western Australia. But in Victoria, it proposes to invest just $400 million: $67 per head, compared with $258 per head, almost four times as much, on people living in Liberal-run states.

Moreover, on budget day infrastructure minister Warren Truss wrote to the Victorian premier, Daniel Andrews, to demand that his government repay the $1.5 billion in 2015–16 unless it comes up with “credible options” for alternative “major infrastructure projects of national significance.” This is a surprising contrast to Abbott’s conciliatory tone just last week on Melbourne radio, when he implied that the two governments were negotiating to transfer the money to Transurban’s $5 billion plan for a tunnel and bridge to improve access from the western suburbs to the port and CityLink.

Politically, the issue was settled six months ago. Victorians voted their Coalition government out, and Labor in, at an election in which the main issue was the East-West Link – an expensive and financially unviable project, which on conventional cost-benefit analysis was found to return just 45 cents of benefit for every $1 it cost. At the time, Abbott called the election “a referendum on the East-West Link.” To some extent it was, and his side lost.

Maybe yesterday’s hardline announcements were just a bit of foreplay for the negotiations that will ultimately see Victorians’ taxes flow back into Victorian infrastructure. If not, Liberal MPs in Victoria will have good reason to be afraid. Abbott is very unpopular in Victoria already, and this is a fight he can’t win. Victorians want him to govern in their interests, not to play politics like a fifty-five-year-old adolescent. Tony, six months ago, you lost the battle. Move on, mate: you’re not a student politician now, you’re the prime minister.

The budget puts its faith in small business to stimulate the economy: just a year after axing Labor’s policy of allowing small business to instantly write off small purchases of equipment against tax, the Coalition has now produced a grander version of the same thing. The original didn’t give much stimulus to the economy, so we can be sceptical about whether the new version will either.

So what would work? Investment in infrastructure. Abbott used to say that he would be the infrastructure prime minister, but the national accounts show that since early 2013, excluding defence, government infrastructure spending has declined by 12 per cent, and is now at the lowest level since the global financial crisis. This is one of the things Glenn Stevens was referring to last month when he urged governments to give central banks more help in stimulating growth. Well-chosen infrastructure projects improve accessibility, reduce congestion and, hence, raise productivity. But apart from thumbing its nose at Victorians, there was nothing new on infrastructure in this budget.

Many in the commentariat have attacked Hockey and Abbott for not pressing on with budget repair. But on macroeconomic grounds, Hockey has a strong defence. It would be absurd if the government brought down a contractionary budget while the Reserve Bank is trying to stimulate the economy by reducing interest rates. As wiser souls have pointed out, the task of fixing the deficit is essentially a medium-term one, and it requires a medium-term plan.

The bottom line now is that the Coalition’s plan is to get the budget back in surplus by slashing billions of dollars a year from the foreign aid budget – because the poor who would benefit from our aid don’t vote here – and by shifting increasingly large health and education costs to the states. That implies that the states will have to seek a bigger, more comprehensive GST, and I suspect the reason Abbott is thinking of an early election is that it is in his interests to face the voters before Australians realise that.

And the third engine of its supposed path to surplus is that friend of many budgets, Rosy Scenario. Australia’s average rate of growth this century has been 3 per cent, and that is what the IMF and others now see as our normal growth rate. But the budget opts for Rosy. It assumes growth will accelerate to 3.5 per cent from 2017–18 despite the mining investment boom crashing back to earth, the car industry folding, and our main customer, China, struggling with the legacy of a decade of overbuilding.

Well, we could be so lucky. And if this budget convinces the punters, the government clearly must be on a lucky streak. This is just the kind of budget that it used to attack so fervently, in the days when it was in opposition, and governing seemed so easy. •