Chinese politicians don’t rise to power on the back of manifestos. This is the luxury of operating in a system in which there is no overt competition for power. But they do make promises. And like politicians everywhere, they talk a lot.

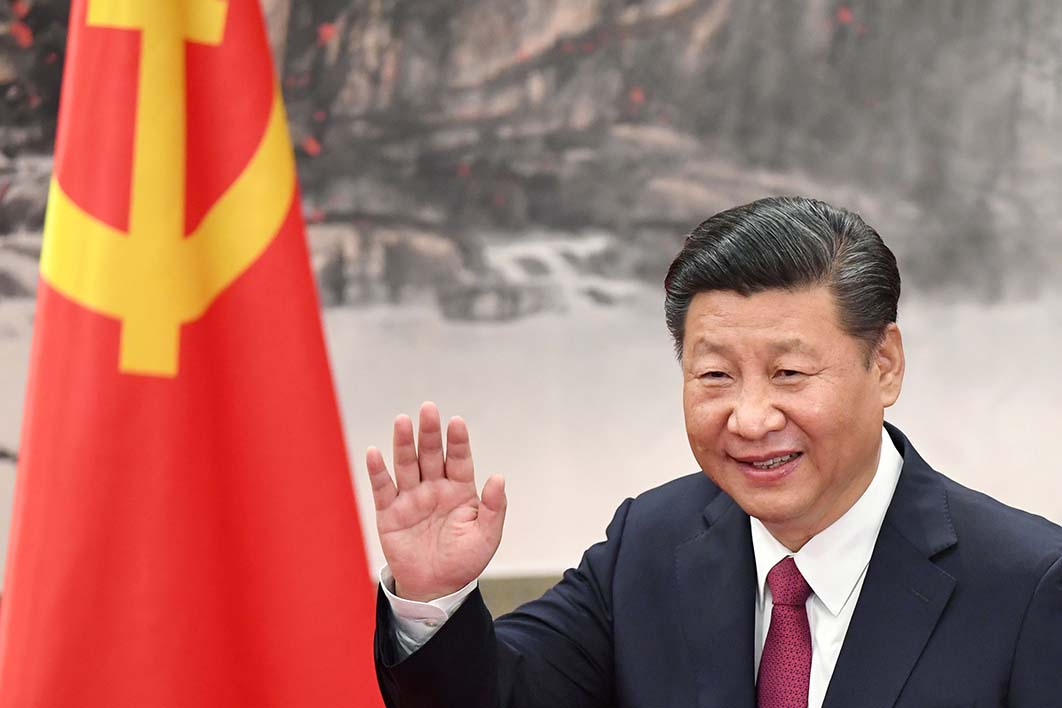

When Xi Jinping stood up to make his epic three-and-a-half-hour political report to the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which concluded this week, his words partly filled the traditional function of reflecting on progress over the five years since the last grand meeting — the one at which he was elevated. It wasn’t an administrative or economic report, with long lists of statistics about growth targets met, GDP maintained, industrial outputs increased; those are dealt with at the National People’s Congress and the State Council. This was a party report to the party — and that means political content.

When Xi emerged as dominant leader in November 2012, he made a few brief comments that stood as a kind of manifesto. The first of its three core areas was the need to serve the people better and close the gap between the people and the party. The second was the need to ensure that China fulfilled its mission to be a great country — in his words, to “rejuvenate the nation.” Finally, he committed to defining more clearly the role of the party in Chinese society.

How much progress has been made in these areas? On the first, Xi’s high-profile anti-corruption struggle has been an enduring feature of his time at the top. Unlike earlier “strike hard” campaigns, which tended to last just a few months, the crackdown since 2013 has been severe, extensive and sometimes dramatic. Precedents have been broken. Former and current Politburo members have been dragged down in its wake. Thousands of people have been directly affected across the country.

The great cleansing has proved popular with the public, despite scepticism that it can really solve the core problem of the party’s being its own judge and jury. It has disciplined the party elite and improved its image. In the era of Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, with its fast growth and endless commercial opportunities, officials, particularly at the local level, were regarded as princes of larceny and selfish greed. Now, they are forever looking over their shoulders, and are more focused on their service and work. It’s good behaviour from fear rather than ethical conviction, but at the moment that suffices. The gap has been closed.

National rejuvenation, meanwhile, is well in hand. Xi has a moral narrative here that extends back to before he came to power. It is working to rectify the crimes and humiliation visited on China in the early modern period, when it endured colonisation, attack and subjugation. In 2017, with a United States distracted and divided, and Europe still fighting its own internal battles, China has never had more international space it can choose to move into. Xi has been the face of this resurgent China, visiting almost fifty countries and, in his own words, telling the China story proactively. This can be regarded as one of his greatest successes, though he has been ably assisted by the dismal instability elsewhere.

In dealing with the third issue, clarifying the role of the party, Xi’s strategy has been simple. Ideological campaigns, fierce “mass line” work and a party-building program, all in combination with the anti-corruption struggle, have shifted the party away from the commercial focus of the Hu years back to political priorities. The Communist Party under Xi has a stronger identity and a clearer role, and is more united. The boundaries between its work and that of business have been sharpened.

But this last point is also a source of problems. One of the striking features of the Congress itself was the fact that it seemed remote, highly elitist and introspective — an elite speaking its own dialect, focused on its own culture, and somehow unable to connect with the wider world. The key ideological formulation that it endorsed, Xi Jinping Thought, with its core idea of modernisation of socialism with Chinese characteristics, is hardly likely to light up the souls of Chinese people with passionate fervour. At most, it seems a bit retro, with many talking of a return to the Mao era, despite the vast differences between the country then and now.

The party clearly wanted to speak to the outside world. But the message it conveyed was an unexciting one. It wanted to display unity, discipline, control — dull virtues that would reassure domestic and international audiences. In many ways, it succeeded. This was a Congress in which progress and routine were victorious, and nasty surprises minimised. Even the line-up of new Politburo Standing Committee members on the final day observed the rules: those meant to retire retired; Li Keqiang stayed on as premier; the number of members remained the same; promotions were broadly routine in terms of age and seniority.

All of this appearance of calm purposefulness only alerts us to the immensity of the task facing these people, with Xi at their centre. They must deliver a rejuvenated nation, maintain solid economic growth, grapple with environmental problems, and try to construct a welfare system fit for purpose in a country where people are living longer and expecting more. The Chinese people, Xi said in 2012, are the masters, and that mantra was maintained in 2017. On this view, the Congress was a meeting of servants — and expectations of them are high. Added to this is the even more frightening issue of the instability of the world around them. Never has China been more important and its stability at a higher premium.

So we shouldn’t interpret the calm, purposeful, almost mechanical air of this Congress in 2017 as a demonstration of effortless, all-conquering power. On the contrary, it is an indication of the deep structural challenges the country is facing, with a political system that, at least in other countries that have tried a communist one-party system, has not lasted into an eighth decade.

Aged almost seventy, communist China is coming close to a number of fateful benchmarks. Middle-income status, overtaking the Soviet Union in terms of longevity, becoming the world’s largest economy… the list goes on. Its leaders face superhuman challenges. They need all the power, and luck, they can get in trying to get to the next Congress, five years hence, in one piece. Otherwise, the calm this year will seem in retrospect to have been the calm that precedes a storm. •