Last Friday it finally happened: Barnaby Joyce reached the summit. For the first time in living memory, the federal National Party is being led by someone most Australians are able to name. Is this a positive development for the party and the Coalition?

Joyce arrived in Canberra in July 2005, one of four Queensland Coalition senators who tipped the Howard government into a surprise upper house majority. He quickly set about constructing a maverick persona, publicly opposing government policy, crossing the floor when it made no difference and threatening to do so when it would have. His indulgences earned him the ire of some Liberals: he was photographed being heavied by Bill Heffernan; Wilson Tuckey called him “a dopey so and so.” And he also, no doubt, made a few Nationals grumpy, but they felt obliged to be more circumspect.

Mavericks in Australian politics generate personal capital at the expense of their party’s. Their “tell it like it is” routine only works because their colleagues do the right thing as team players.

Mavericks are wont to claim that they are too free in spirit to reach the cabinet heights, but usually the causation runs the other way. They tend to be individuals whose talents haven’t, in their view, been sufficiently recognised by their colleagues. Labor MP Graeme Campbell put himself forward for a ministry in the early 1990s and, after he was rejected, became a vocal critic of prime minister Paul Keating (and left the party several years later).

And if John Howard had offered Kooyong member Petro Georgiou a frontbench spot in 1997, rather than the parliamentary secretary position Petro felt beneath him, the straight-talking Liberal conscience journalists came to adore would never have been born. Cabinet ministers aren’t allowed to freelance.

Joyce’s antics, by contrast, have simply fuelled his rise. His success is a function of his party’s struggle against its shrinking relevance. Tired of being taken for granted by its Coalition partner, regularly under threat from independents and third parties, the party has among its rank-and-file members many who see Barnaby as its best chance of reliving former glories.

In 2008, during the Coalition’s first year in opposition, Joyce’s colleagues installed him as Nationals leader in the Senate. The following year he led a revolt against the Coalition’s deal with the Rudd government on an emissions trading scheme. In December 2009 a new opposition leader, Tony Abbott, brought him fully inside the tent as shadow finance minister.

Abbott praised Joyce as “the best retail politician in Australia,” and he certainly does possess great presentational talent. He puts his personality into it, mixes it up and expresses the chosen political theme in distinctive ways. A message is more likely to take hold in recipients’ minds if it requires them to exercise some grey matter, to join the dots. Joyce’s metaphors do that.

He is fond of saying that Australians want their politicians to be “real” (like him) but that’s only true up to a point. When it comes to running the country, voters prefer leaders who are steady, safe and reliable.

The same applies to occupants of important economic portfolios. Shadow finance was a preposterous captain’s pick, unsuited to Joyce’s free-form, intemperate style, and he was humiliatingly dumped three months later. In the agriculture portfolio he has found an effective balance between flamboyance and cabinet solidarity – though at times, it must be said, he seems strained, like a caricature of himself.

But, like his stint at Finance, Joyce’s move to the Nationals leadership is going to end in tears. How can it be otherwise?

After Tony Abbott led the Coalition to victory in 2013, Andrew Robb became the first Liberal trade minister since the mid 1950s. His recently announced successor, Steve Ciobo, is also a Liberal. From John McEwen in the late fifties and the sixties, through to Warren Truss at the end of the Howard era, that position in a Coalition government always went to a Country/Nationals MP, and usually to the leader. Imagining Joyce in Trade sends an unpleasant shiver up the spine and reminds us how much the world has changed.

The Coalition partners’ parliamentary numbers tell a similar story. When Robert Menzies took office in 1949, the Country Party occupied 24 per cent of the government’s seats across both houses. The next time they entered government, in 1975, the proportion was about the same, at 24.6 per cent. By 1996 the figure had dropped to 19.1 per cent, and now it’s just 17.1 per cent.

If their shrinking significance and representation means Nationals are no longer automatically entitled to Trade, will the day soon come when the same applies to the deputy prime ministership?

Seats that Liberals have taken from the Nationals in recent years, including Farrer (whose MP is Sussan Ley) and Hume (Alby Schultz, then Angus Taylor), have maintained their large two-party-preferred margins against Labor, with little in the way of third-party or independent threat.

Which raises the question: what’s the point of the Nationals these days? With every decade they are less a political entity in their own right and more a faction of the Liberal Party. Like Labor’s left, the best they can realistically hope for is to be thrown the odd scrap.

The Barnaby leadership represents a desperate attempt to reverse the trend, but it is not sustainable. The best outcome for the Coalition, and hence the National Party, would see him employing his rhetorical skills to turn sows’ ears into silk purses for the Nationals’ true believers. But without a tangible turnaround in the relationship, they will tire of that, and he’ll end up just another politician.

The biggest danger of the Joyce appointment is that heightened Nationals expectations, unmet, will lead to a Coalition split. The least likely eventuality, that the Nats actually end up wielding substantially more clout, would be dysfunctional because it’s against the reality of shifting electoral support.

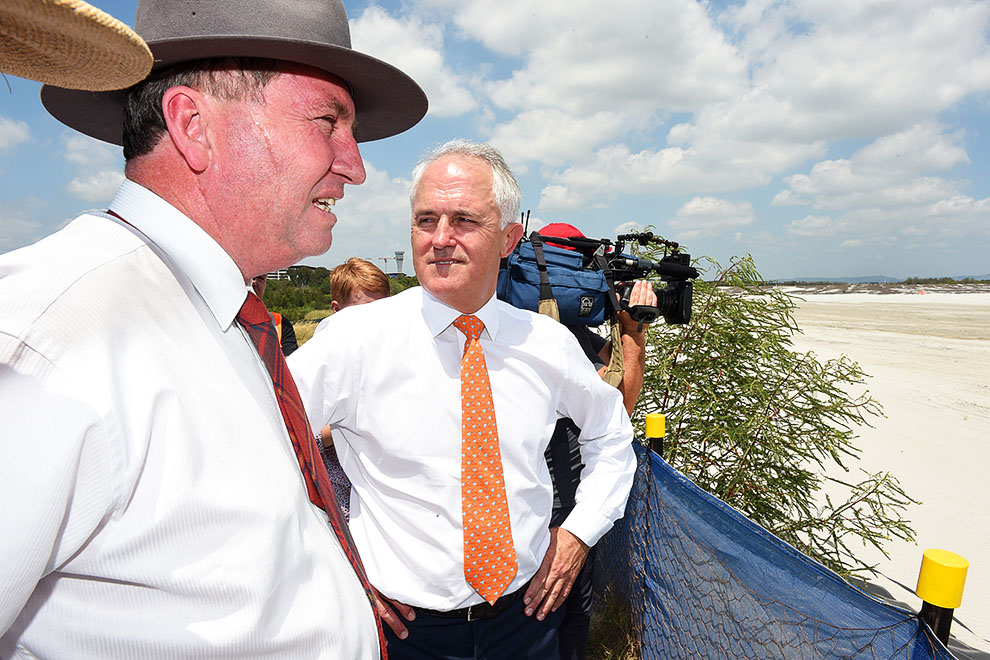

It would provoke a backlash from the Liberal Party and its funding base. And it is difficult to imagine a Liberal leader less attuned to the sensitivities of the relationship than Malcolm Bligh Turnbull.

Mavericks are selfish attention-seekers who are unable to admit they would be nobodies without their party, and are rarely leadership material. You could call Barnaby’s elevation a risk for the Coalition, but that would imply a potential upside. •