Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Jailed five times and acquitted a further five times in her twenties, Catherine Henrys consistently displayed contempt for those in authority. Her long history of criminality included breaking a convicted felon, William Golding, out of prison and assaulting an officer. When she was sentenced to transportation for life for “stealing money from the person” in 1835, she was described in court transcripts as being “associated with persons of the worst description.” Far from being cowed by the transportation experience, she persisted in her rebelliousness in colonial Australia.

Born in County Sligo, Ireland, in about 1806, Henrys moved to England and fell in with a gang of criminals. At five feet six inches, she was tall for her time, and she was described as having pale, pock-pitted skin, black hair and hazel eyes, with a tattoo of a cross on her right arm. On the journey from England to Van Diemen’s Land, according to the ship’s surgeon’s journal, she contracted pleurisy, a debilitating lung illness similar to pneumonia. The surgeon also described her as being “very bad” and “incorrigible.”

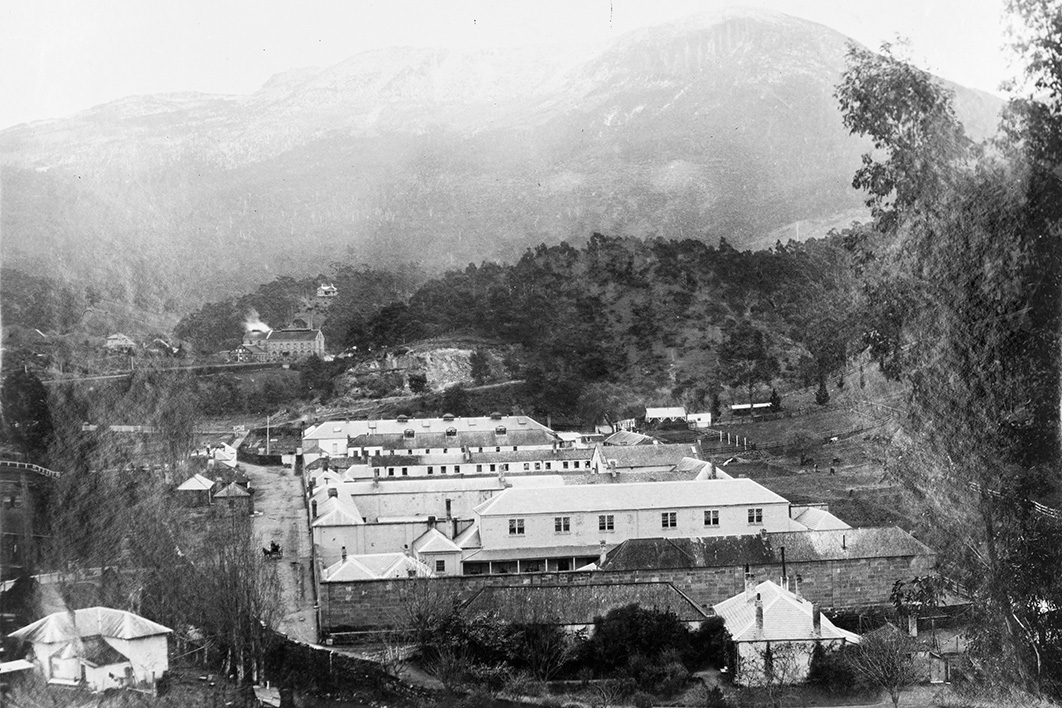

Henrys arrived in Hobart on the Arab on 25 April 1836. Over the next fourteen years she was convicted of forty-nine offences, primarily involving disobedience, drunkenness, assault and misconduct, in the form of “profane, beastly and threatening language to the constables.” She was also convicted numerous times of absconding. In one instance, in 1841, she left her place of servitude (convicts were often assigned to free settlers as labourers or domestic help) and lived in the bush for a year, during which time she dressed as a man, went by the name of Jemmy the Rover, and worked as a timber splitter. She was caught and returned to the Cascades Female Factory, a workhouse for female convicts, and earned a further six months’ hard labour on top of her original sentence.

Of one court appearance, the Hobart Colonial Times reported on Tuesday 24 March 1846:

Yesterday, a powerful virago of a woman, named Catherine Henry [sic], holding a ticket-of-leave, was charged by Constable Sharpe with being drunk and absent from her authorised place of residence. The “fair penitent” was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment, with hard labour. To this, she demurred and alleged that those rogues of constables always sacrificed her, and for what she did not know, inasmuch as she was a most quiet and peaceable person. Hereupon Sharpe declared that “Miss Henry” was “flaring up” with a large lot of whalers, sailors, and other roisterers. “Miss Henry” was then conducted from the dock, and, as the door to the cage was opened for her reception, she suddenly, and with most Amazonian vigour, attacked the constables right and left, dealing such mighty blows as would have well become the immortal Boadicea herself. Of course, a rumpus took place, but “Miss Henry” could not be pacified; blows were given, and as to tongue, we could not, if we would, chronicle the language.

Returned to the dock, Henrys again protested at the “oppression” of the constables. “She was cautioned by his Worship,” concluded the paper, “and carried away as before, uttering loud exclamations and, indeed, most bitter imprecations against all in the office.”

Her initial ticket of leave was granted in 1845 but revoked five times over the next decade. In January 1848 she was convicted of assaulting a constable and was sentenced to nine months’ hard labour at the Cascades Female Factory. Within weeks she had escaped by sharpening the end of a spoon to pry out a cell bar and then climbing a stack of tubs, having fashioned a rope from her blanket to let her down on the other side. The Launceston Examiner reported that this “notorious female” had a reputation as a pugilist, and claimed that her “masculine” appearance was quite in keeping with her character.

Henrys married former convict Samuel Dobbs in 1849 but remained rebellious to the last. In November 1850 she and two other women were charged with robbing a man of £3 10s in a house of ill fame. When the victim declined to prosecute, the charges were dropped. But Henrys was found guilty of having afterwards smashed five panes of glass and part of a sash with a rock at the next-door neighbour’s house, and was sentenced to the Cascades Female Factory for one month.

On 19 December 1850, while Henrys was still incarcerated, Samuel Dobbs left Launceston for Melbourne. In March of the following year Henrys, too, embarked for Melbourne where, although it is hard to imagine, there is little evidence of further infraction. She died of cancer at Melbourne Hospital on 15 August 1855, as Catherine Henry, aged forty-nine. •

Further reading

Convict Lives: Women at Cascades Female Factory, by Lucy Frost, Female Convicts Research Centre, 2012