The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia

By Dane Kennedy | Harvard University Press | $49.95

THIS fine book breathes new life into the history of exploration. In a fresh and creative way, Dane Kennedy juxtaposes the familiar stories of the European exploration of Australia and sub-Saharan Africa, enlivening the histories of both continents. The well-known explorers – men like Livingstone, Burton, Speke and Stanley in Africa and Leichhardt, Sturt, Eyre and Mitchell in Australia – occupy centre stage, but Kennedy also examines the intellectual and political forces in the European heartland that underpinned the whole venture and the institutional support that made it possible.

A project on such a scale required extensive research in libraries and archives in Europe, Australia and North America, as well as familiarity with the extensive secondary literature. Kennedy’s bibliography lists 400 books and articles, and his research into the Australian records is reassuringly thorough. But the narrative is not impeded by excessive detail, and precise and elegant prose carries the reader effortlessly forward.

In the process, Kennedy offers many ideas and arguments that illuminate the history of Australian exploration. A most interesting insight emerges from the way he describes how the methods and technology developed by the great maritime explorers of the eighteenth century were used in the following century by their terrestrial successors. This strengthened the emerging tendency to treat both continents, like the oceans themselves, as blank spaces; and it was much more effective and instrumental than a metaphor because it added impetus to the custom of seeing the great continental spaces, if not without people, then without political boundaries or systems of land tenure.

In Australia, this approach merged effortlessly with the doctrine of terra nullius, even though explorers themselves became aware of the ubiquitous Aboriginal presence, the power of traditional custom and the intense sense of territoriality. Comparing the two continents, Kennedy observes: “Unlike African maps, Australian ones never gave any indication of the existence of Indigenous polities and presence on the land. Cartographically, the continent was characterised as terra nullius from the start, a view that explorers’ encounters with Aborigines did nothing to change.”

The explorers became heroes in both Britain and Australia. In part this was due to the fact that they were seen as much more than mere travellers. The ideal explorer was a man of many parts: a surveyor, a map-maker and a botanist, with some acquaintance with geology and meteorology. This helped distinguish land exploration from the oceanic variety. Sailing ships could carry stores and equipment unavailable to even the largest inland expeditions and they commonly provided berths to assorted scientists and artists. But the explorer became a heroic figure of the Victorian era because they were seen as harbingers of civilisation and Christianity. In Africa, exploration had the additional motivation of carrying the crusade against slavery into the heart of the continent. In Australia, the process was reversed: explorers paved the way for pastoralists who subjected generations of Aborigines to a system of forced labour little different from slavery.

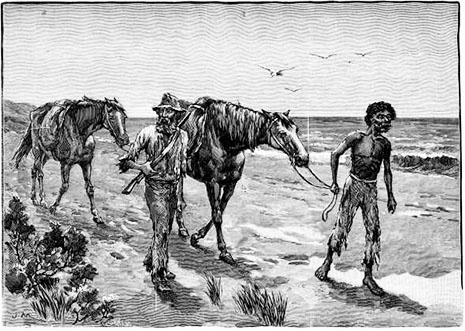

The apotheosis of the explorer left little room for the inconvenient fact that on both continents most expeditions were heavily dependent on the guidance and expert advice of assorted Indigenous advisers. Kennedy observes that explorers in both continents “were often weak and vulnerable. Far from demonstrating the great power of the British Empire, explorers in fact discovered its limits and learned that their success and, indeed, their very survival often depended on their ability to obtain local assistance and acquire local knowledge.”

It is only by reading between the lines of the journals of Australian explorers that we can understand the importance of the often-unnamed “Blackboys” who accompanied most inland expeditions. And the same was true of the innumerable and largely unrecorded private parties who ventured into Aboriginal Australia throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century. •