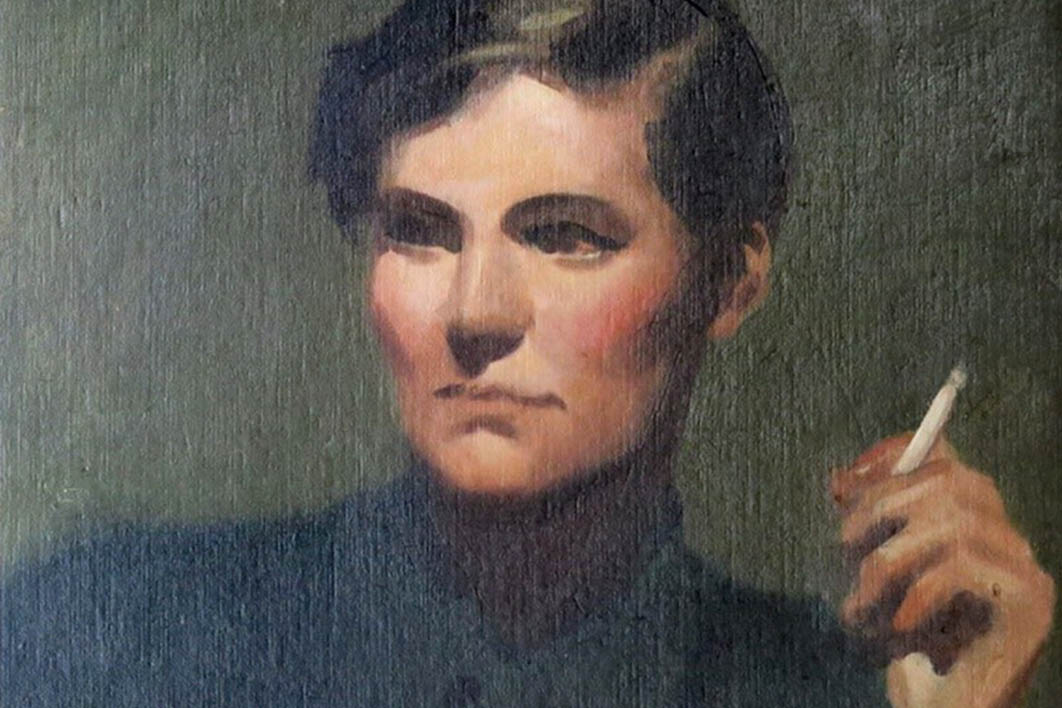

“I suppose you’d like to see the portrait before we have coffee.” The smiling woman who had greeted me at the door of her elegant Art Deco flat, typical of the 1930s Melbourne in which it was built, gestured towards the living room and ushered me in. On the wall next to the window overlooking the front garden I saw a group of four framed portraits. Three were of the same man painted by different artists. The fourth was of a striking young woman with short hair and high cheekbones, cigarette in her raised hand, caught as if in earnest conversation with someone just out of view. I knew every line of this portrait but the immediacy of seeing the original, in colour, made my skin prickle and my eyes blur.

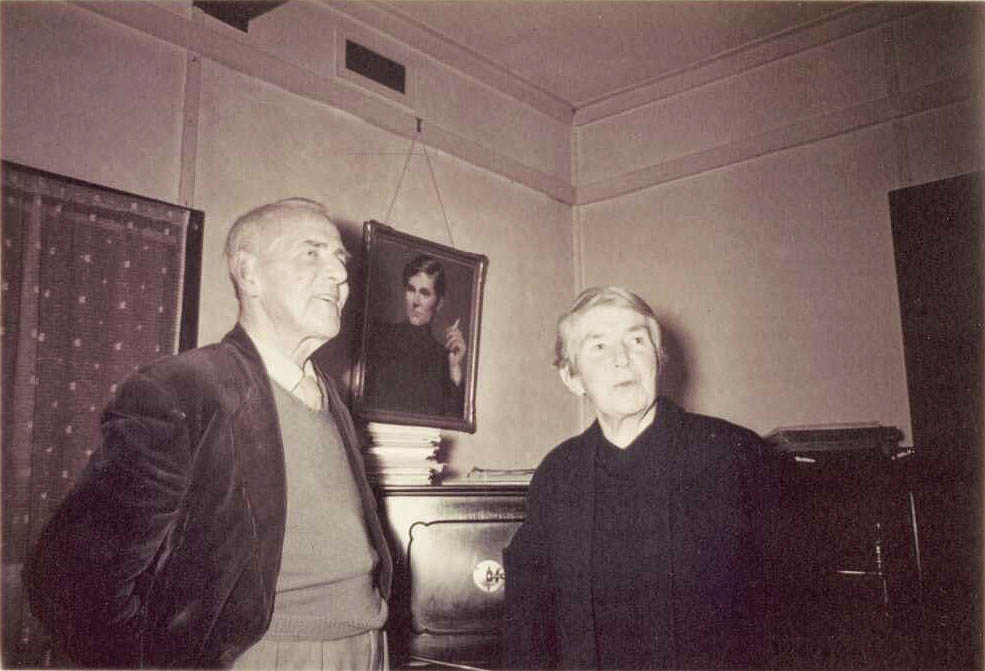

During the research for my biography of poet and political activist Aileen Palmer in the National Library of Australia, I had found a snapshot of her parents, Australian writers Vance and Nettie Palmer, taken in their living room in the 1950s. On the wall behind them I could see a large portrait in a heavy gold frame of a young woman. Realising it must be a portrait of Aileen, I hunted through the realia in the Palmer archive.

I found two framed portraits painted in an impressionistic style by Peggy Maguire in London around 1939: one in brown tones of Aileen’s sleeping figure and the other in shades of blue in which she is reclining on a bed, reading, a red cushion at her back and shadowy outlines of books at the bedhead. Neither was the one I saw in the snapshot taken at Ardmore, the Palmer family home in Kew, just a few kilometres from where I was now standing.

Where could she be? Vance and Nettie Palmer with the portrait of Aileen in background, probably in the 1950s. Palmer Collection/National Library of Australia

I began my biography with an account of the missing portrait, describing Aileen’s appearance in it as “androgynous” and “bohemian.” “The portrait is so immediately striking,” I wrote, “you want to know who she is and when it was painted. Where could she be? In a cafe, in Paris perhaps? You feel almost as though you could meet such a young woman walking along a city street today…”

I outlined what I knew of the portrait from Aileen’s letters to her parents from London, where she was living in 1938. She had recently returned from two years on the frontlines of the Spanish civil war working as an interpreter and administrator for medical divisions of the International Brigades. A passionate communist from her university days in Melbourne, she had joined the fight to save the elected Republican government in Spain from General Franco’s fascist rebels.

Aileen wrote to her mother on 25 July that Australian artist Madge Hodges, a former student of Max Meldrum, had asked her to sit for a portrait. Madge was a neighbour with a top-floor studio in Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury. According to Aileen, she was “quite a decent Meldrumite painter… She seems rather frail and limp, but is quite awake to things.” A month later, on 25 August, Aileen reported: “I spent part of two evenings this week sitting as a model for Madge Hodges, who painted you once in Australia… She asked me if I would sit for her, as she didn’t think I would be the kind of sitter who would ask her to lengthen my eyelashes, etc. thus more or less inducing her to falsify her work as some sitters do.”

Nettie Palmer’s diary also mentions the portrait, noting that it had been brought back to Australia by a family friend in 1940 and was framed and ready to hang in the living room at Ardmore ten days later. “Remarkably good” was her verdict. “Rather dominant — Napoleonic, conducting the world with a cigarette.” She reported that Vance too was impressed.

Seeing the portrait in colour for the first time made me aware of how closely Madge Hodges had followed the strictures of Meldrum’s “Tonalism,” in which the light or darkness of colours and how they relate to each other was the defining feature. The palette was restricted to five tones and outlines were forbidden. According to art critic John McDonald, writing about the Misty Moderns exhibition in 2009, the paintings that resulted were “remarkably similar in their blurred edges and smudgy, atmospheric surfaces.” A “penchant for gloom” seemed to be a temperamental preference among Meldrum’s students, he added. In Madge Hodges’s portrait, Aileen’s head emerges from a dark background while the deep blue of her dress almost disappears into it. All emphasis is on her face and the raised hand holding the prominent cigarette. The effect is anything but gloomy. The glowing portrait is arresting in its strength and vitality.

In her published diary, Fourteen Years, Nettie Palmer recalls going to an exhibition at the Meldrum Gallery in 1933 where there was “a good mixed show: Jorgensen, Colahan, Leason, and some younger ones, also Meldrum himself. All displayed by strong electric spotlights, the rest of the Gallery correspondingly dark. Good method for their kind of tone-values; other painting might be flattened by it.”

Max Meldrum was a charismatic teacher and Melbourne was the heartland of his “school” in the early decades of the twentieth century. Clarice Beckett was his most favoured student; his other female students have been mostly forgotten. Beckett, who never left Melbourne, died at the age of forty-eight in 1935 but several of Meldrum’s best-known students, including Colin Colahan and Percy Leason, went to Britain and the United States and never returned. Little is known about Madge Hodges, but she was still in Melbourne in 1936 when she illustrated an article for anthropologist Ursula McConnel in the journal Oceania. A painting of hers is listed in an exhibition of Australian expatriate artists at the Imperial Institute Art Gallery, London, in 1956, which indicates that she remained in London after she painted Aileen Palmer in 1938. Colin Colahan exhibited paintings and sculptures there, and other artists listed in 1956 include Arthur Boyd, William Dobell, Sidney Nolan and Rolf Harris.

Nettie and Vance Palmer were caring parents, proud of their elder daughter’s fierce intelligence and the linguistic abilities that saw her receive a first-class honours degree in French language and literature, with a thesis on Marcel Proust, at the age of twenty. They supported her political activities too, although Nettie wished she would settle down and concentrate on her writing. But when Aileen returned to Australia in 1945 after a decade on warfronts she was unable to adapt to her homeland. She felt “a foreigner,” she said, even though her parents provided the support for her to write. As her life began to unravel, she suffered a first breakdown in 1948 and was then in and out of mental institutions until she died in 1988.

The missing portrait seemed to symbolise for me the tragedy of Aileen Palmer’s life. All I was able to see in the small snapshot was a glimpse of a dynamic young woman pinned like a butterfly on the wall behind and between her well-known parents. This was the woman who vowed to get out from under what she called “their august and all-pervasive shadows” when she joined the British Medical Unit in London in 1936 and set off to war in Spain. Ironically, after driving ambulances during the Blitz in London, she returned to the family fold when she came back to Australia, and Vance’s and Nettie’s shadows were to blight the rest of her life. That the portrait painted in the 1930s, when Aileen was at her most liberated, was lost added another symbolic dimension.

Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer was published by UWA Publishing in early 2016. I had just returned from overseas engagements talking about Aileen Palmer’s involvement in the Spanish civil war when I received an email from a Penelope Pollitt. Her surname caught my attention because Harry Pollitt had been the general secretary of the British Communist Party when Aileen was co-opted into the first medical unit to travel to Spain. The unit was, in large part, formed under the auspices of the party. It turned out that Penelope’s former husband was Harry’s son, but that was not why she was writing to me. She said she had “read and re-read” my book, adding that “Aileen Palmer was a presence, not always a welcome one, in my life during the 1950s when I was a teenager.”

Penelope’s parents were members of the Kew branch of the Communist Party, which she described as “an active, engaged, argumentative, inclusive branch of the party.” Her father Cedric Ralph was a lawyer who had led the Victorian legal effort against the Menzies government’s push to outlaw the Communist Party. In her memoir The Hammer & Sickle and the Washing Up, Amirah Inglis, who was working as a clerk for Cedric during the Royal Commission into the Communist Party in Victoria in 1949, described him as

a lean and elegant man with lively bright blue eyes and the gentlemanly manner of the son of a Melbourne professional family. He had left the family law firm and set up on his own, married the beautiful daughter of a wealthy Melbourne business family and lived in Kew; but with that, and their cultivated voices, ended the similarity to the neighbours. Cedric and Rhea Ralph were devoted Communist Party members; their fine Georgian house was the setting for meetings, “cottage” lectures and concerts, and their three daughters were schooled at progressive Preshil.

Aileen Palmer was a member of the Kew branch and regularly attended the meetings and socials at Penelope’s family home. “She showed no interest in me,” Penelope wrote, “and I found the pervasive smell of cigarettes and her uncared-for appearance very off-putting but the fact that she was a poet impressed me.” Penelope’s friend Muriel Arnott, the daughter of branch member Muni Bowen, remembered Aileen as “always around,” “cantankerous” and often ill, being looked after by her mother and others in the branch.

Penelope was surprised that the Kew branch did not feature more in my biography. “The party was a powerful influence in most areas of life in those days,” she wrote. “Its influence extended to relationships, friendships, even marriage. Its network was so extensive it determined which doctor you consulted, which lawyer you went to, which trade union you joined, even in some cases which business you dealt with.” I had been aware that Aileen belonged to the branch and I knew that she had given a talk to the Kew Peace Group when she returned from a peace conference in Tokyo. But she didn’t write about her time in the Kew branch in any of the autobiographical fragments in her archive, although she was, as Penelope remembers, “so much part of this world.” The 1950s were difficult years for Aileen and she spent lengthy periods in Sunbury and Royal Park mental hospitals. She found writing difficult when she was depressed, as she was during much of this time.

It appears that Vance and Nettie, who were left sympathisers but not Communist Party members, did not altogether approve of the influence of the Kew branch members on their daughter. When Aileen was asked to be part of the delegation going to a world conference against atomic and hydrogen bombs, to be held in Tokyo in 1957, she stopped taking the medication she had been prescribed to control her mood swings. She was also drinking heavily and the situation at Ardmore was grim.

“There are a lot of loyal friends around her but they haven’t much sense,” Vance wrote to his younger daughter Helen in Sydney. “The night before she left was rather a wallow with all sorts of people coming to Muni’s and bringing bottles. The truth is they seem to enjoy her when she’s het up and pouring out words.” While it is understandable that Vance found any encouragement of her drinking distressing, Aileen’s friends at the Kew branch do appear to have provided her with an alternative “family” where she was able to be herself free from surveillance. As Muriel Arnott remembers, her mother Muni and others in the branch “were always there for her.”

Towards the end of Penelope’s letter I was surprised to read this: “All my memories of Aileen are of the 1950s. But she is still a presence in my life as I am the possessor of the portrait you refer to in the opening paragraph of your book.” She signed off soon after without further explanation of how she came to possess the missing portrait, but her email did contain an attachment.

Cedric Ralph, Penelope’s communist lawyer father, began his autobiography at the age of eighty-two on his first computer. He died aged one hundred in 2007 and the attachment Penelope sent me was a few pages from this unpublished work, in which he writes about his friendship with Aileen Palmer.

Their friendship began after Aileen returned to Australia in 1945. Cedric remembers picking up “the girls” (Aileen and Helen, who was still living at Ardmore then) to take them to the monthly party meetings. “From about 1947 on,” he wrote, “Aileen and I became real friends. She was an extraordinarily warm-hearted creature, of very deep feelings, maybe too deep… On those short car journeys we often talked, sometimes at length. I thought her emotional approach to political questions often led her astray, often we did not agree.”

When Aileen suffered her first breakdown in 1948, she underwent a gruelling series of interventions in a private psychiatric hospital, including insulin coma therapy and electroconvulsive shock treatment, without sedation. She also began psychiatric treatment with Dr Clara Lazar Geroe around that time. Her psychiatrists diagnosed Aileen as a manic depressive, but Cedric did not accept a division between the mental and physical, believing that “so-called mental illnesses have a direct physical basis.” He writes movingly about her periods of deep depression, which tended to last just a few weeks:

Sometimes in her periods of depression, she would drop me a note demanding I take her to lunch. It appeared to me I gave her comfort simply because I treated her as being normal in a way that I gathered few others did. It was indeed sometimes difficult to be in her company while she gave no response at all. Often she would say nothing, just nod occasionally or give a tolerant glimmer of a smile. For all that, as she left after such a lunch, her thanks were warm.

On the other hand, when a “high” came on “she was fond of writing sonnets and these she could compose faster than I can write a quarter page of these memoirs.” Most were directed towards political and social issues, but some were personal and Cedric was the recipient of one of Aileen’s sonnets. “In 1961, a few days after I told her I planned to go to London, she asked me to call on her,” he writes. “Rather shyly, she was too straightforward to be really shy, she gave me an envelope.” It contained the following sonnet:

To C.R.

You gave me courage once that was denied

To those that fed on flowers of phantom seeming:

To those whose only courage was their

dreaming: You gave me courage permanent and wide.

You gave me courage, that is worth a lot

At this dull moment, in this arch of time

Courage is all my heart puts into rhyme

Courage, the plant we grow in this neat plot

The plant that seemed to perish when the wind

Blew swift and hard across Hungarian steppes:

Our world then seemed to shatter, to its depths

Among those who lived harder: though you’ll find

A love of life, that clings, just like a burr:

A depth of knowing, that no breeze can stir.

A.P.

“I could not have been more moved,” Cedric responded. “The differences in our political appreciation of current events troubled me not at all, the general motif of the lines made me realise, perhaps for the first time, that each of us has influence and that influence we can use for better or for worse. And that it takes thought to use it for the better.”

Not all recipients of Aileen’s personal poems were as generous. Dorothy Hewett’s first novel, Bobbin Up, was published in 1959, but only after it had caused a stir among Communist Party officials. Although it depicted the lives of working-class women in a Sydney spinning mill, it was criticised by the moralistic party men for its frank depiction of sex and its “language.” In an autobiographical article in Overland in 1960, Dorothy wrote that at the launch party she “was presented with a very soppy poem written to me by Aileen Palmer, the daughter of Vance and Nettie.” She was clearly disturbed by Aileen’s appearance, continuing, “The next day Aileen in an old and tatty overcoat took me out to lunch and afterwards to meet her mother.”

Cedric Ralph’s and Dorothy Hewett’s contrasting reactions to Aileen’s poetic gestures contain a certain irony: the older man who saw himself as Aileen’s non-judgemental friend understood something new, while the young woman celebrating the publishing of her controversial novel saw only a dishevelled madwoman “looking like a bag lady.”

On the last page of the excerpt Penelope Pollitt sent me from her father’s memoir I finally found out how the portrait of the young Aileen Palmer came to be in her possession. Cedric Ralph wrote:

I felt myself extremely lucky to call on Aileen just as she was organising for sale her old home in Ridgeway Avenue Kew. She was getting rid of unwanted furniture. I asked her “What is to happen to your portrait?” (It was a painting in the Meldrum style and had been hanging for years in her workroom.) She replied “It is for sale.” The price she mentioned as that of her valuer’s was I thought very modest; so I was very happy that it came into my prized possession.

The question that immediately came to my mind on reading this was why Aileen was selling her portrait, painted at a time when she was living in London among friends and writing a novel about the Spanish civil war. She seemed to be thriving then in a way she never did after she returned to Australia. It is not a question I can answer. Interestingly, two other portraits of her did end up in the National Library. Perhaps it is significant that she kept this portrait with her at Ardmore after her parents died, apparently shifting it from the living room to her “workroom,” where Cedric had seen it. It is likely that after Nettie died in 1964 she moved her study to the closed-off upstairs verandah where Vance had always worked, the room that caught the sun and was less gloomy than the rest of the house. As she took in boarders to supplement her finances, she probably saw friends there rather than in the shared living room.

Ardmore was sold in 1977 when Aileen was in her early sixties. Helen stayed living in Sydney until her death in 1979 while Aileen moved into a flat in Reservoir on the other side of Melbourne. The move was not a success and she was to spend much of her remaining years in a ward for long-term patients at Larundel mental institution, dying in 1988 in a psychiatric nursing home in Ballarat, the last of the Palmer family.

Unlike a novel, a biography is never finished, complete within the pages of the text. Writing biography is risky: new material can shed a different light on aspects of the life one has written and conclusions the biographer has drawn may be altered or even debunked; on the other hand, unexpected rewards may come even years after a book is published. It is as though the biographer is in a continuing conversation, if not with, then certainly about, the people she has spent years researching.

Finding Aileen Palmer’s lost portrait did not reveal any crucial new “evidence” about her life, but it has enabled me to cover what Penelope Pollitt saw as an important missing piece of it, that is, the importance to Aileen’s life of the Kew branch of the Communist Party. Cedric Ralph’s memoir — especially his poignant account of the silent lunches he spent with her at her request when she was in a state of depression — adds richness to Aileen’s story. They are a testament to the importance of friendship, even if the “lean and elegant” Cedric and the chain-smoking Aileen in her “old and tatty overcoat” must have appeared an odd couple to the other diners.

Out of the shadows: the portrait of Aileen Palmer hanging on Penelope Pollitt’s wall with three portraits of Cedric Ralph. Sylvia Martin

When Penelope invited me to come and see the portrait I thought she might bring it out of storage for the viewing. Instead, I found it hanging on her living-room wall with three portraits of her father by different artists. The portrait of Cedric Ralph immediately above Aileen’s is by Noel Counihan, who was a friend of the Palmers and who painted the well-known portrait of Vance that accompanies the entry on him in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. The other two portraits are by A.R. (Rem) McLintock (bottom left, painted because McLintock disliked the Counihan portrait) and Miklos Szilagyi (top left). Looking at the lost portrait in full colour hanging in the company of this friend, a member of the party she devoted her life to, it struck me that Aileen had finally moved beyond the shadow of her parents into the light. ●