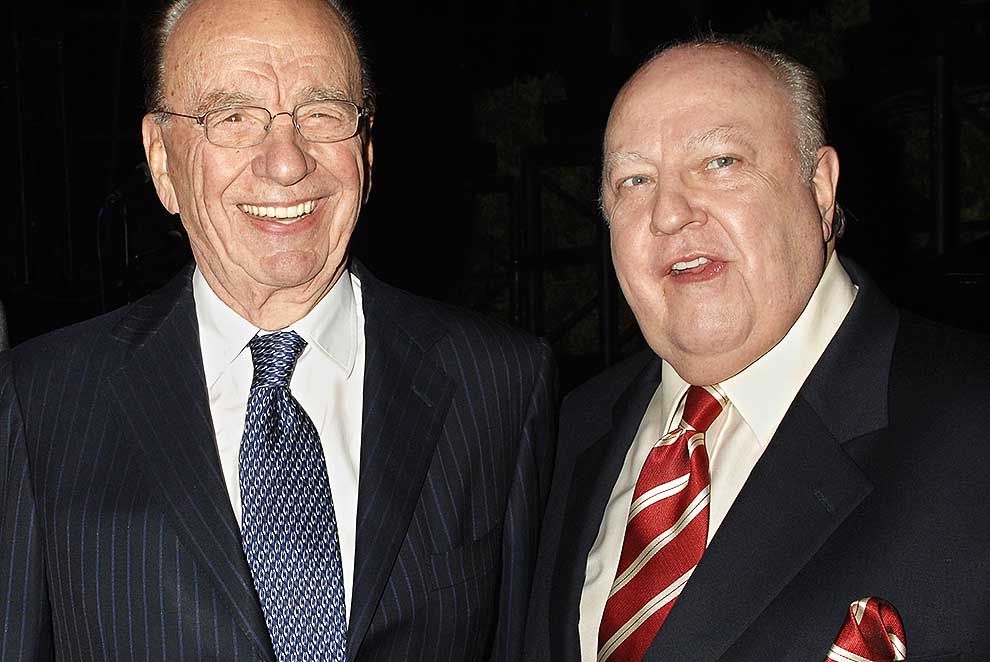

In what was a very ugly year, one of the ugliest things I read was an account of how the dictatorial head of Fox News, Roger Ailes, ran the network. He installed a CCTV system throughout the New York headquarters of the Rupert Murdoch–owned cable television network, essentially creating a surveillance state. Spying Rupert’s son James smoking a cigarette outside the office one day, Ailes remarked to his deputy Bill Shine: “Tell me that mouth hasn’t sucked a cock.”

It’s hard to know which is uglier, the casual homophobia or the creepy surveillance of anyone and everyone connected to Fox, including the proprietor’s son, one of the most senior executives in News Corporation.

That we know this happened is thanks to the reporting of Gabriel Sherman, media writer for New York magazine, who in July 2016 broke the story of the women who alleged that Ailes had sexually harassed them at Fox News. Unlike a later scandal, when Donald Trump’s boasts of grabbing women by their genitals failed to derail his presidential campaign, these revelations had a measurable impact: Ailes’s departure from the television network he had launched for Murdoch in 1996.

I say departure because it is hard to know what word to use when one of the most powerful men in the American media can (a) be forced to leave in disgrace the television network he led so successfully for two decades but (b) receive a massive payout to do so. To be plain: the penalty for being a serial sexual harasser of women was a cheque for US$40 million.

Ailes strongly denied the allegations, but he did leave Fox. No doubt part of the payout was to help him deal with lawsuits brought against him by Fox anchors Gretchen Carlson and Andrea Tantaros.

But just as sexual harassment is about power rather than sex, so Ailes’s payout is about the power he wields rather than justice for the eighteen women who, according to Sherman, came forward in the wake of Carlson’s original allegations to describe a network that operates “like a sex-fueled, Playboy Mansion–like cult, steeped in intimidation, indecency and misogyny,” as Tantaros’s lawsuit puts it.

Power is what Ailes has always wanted. He may have lost much of it now, and it may be that the network he moulded so carefully has been overtaken in influence by far-right websites like Breitbart. But amid the anxiety about former Breitbart chair Steve Bannon’s becoming senior adviser to president-elect Donald Trump, it is easy to forget the role Ailes has played in shaping how both media and politics operate today.

Gabriel Sherman’s The Loudest Voice in the Room: How the Brilliant, Bombastic Roger Ailes Built Fox News – and Divided a Country is essential reading on this score, especially since it was scarcely mentioned in Australia when it was released in 2014. Sherman shows how the seeds of Ailes’s downfall lay in his openly sexist comments about women, his offer in the 1980s to a prospective employee of a pay rise if she had sex with him, and later, at Fox, his insistence that his camera operators focus on women’s legs. At one meeting he barked that he hadn’t spent good money on a glass desk on set for his presenters to be wearing pantsuits.

Sherman’s reporting prepared the ground for women to speak out against Ailes, and for that alone we should be grateful. By 2014 Ailes had become not only one of the most powerful but also one of the most feared media executives in the most powerful country in the world. Researching the book wasn’t risk-free for Sherman: in 2012, according to CNN’s media reporter, Brian Stelter, Ailes directed underlings to build a dirt sheet about him.

The Loudest Voice in the Room reveals in exhaustive detail the extent to which, from very early in his career, Ailes fused the worlds of politics, journalism, public relations and entertainment. It is not simply his trajectory from media adviser for 1968 presidential candidate Richard Nixon to cable network news executive, though that is central to his history, it’s also the fact he has muddied the distinct values of these roles along the way, and there is little evidence he has ever seen anything much wrong with that.

Ailes was hired in 1974 by Television News Incorporated, or TVN, for his public relations skills, but he so impressed the board of the fledgling network that he was made news director a few months later. He saw no conflict of interest, though, in TVN’s offering a paid “image consulting” service to corporate executives. “It seemed appropriate to Ailes that a news organisation could offer PR advice to the very powerful people its journalists were covering,” Sherman writes.

In the early 1990s, when Ailes was setting up a business news network for NBC, he drew a US$5000 monthly consulting salary from tobacco company Philip Morris to provide PR advice. According to internal Philip Morris memos, it was suggested that Ailes should prime Rush Limbaugh, the conservative talk radio host, “to go after the antis for complaining” about a big tobacco PR campaign to protect its markets.

From early in his career, Ailes showed great flair for producing entertaining television. He had studied Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films for the Nazis, and particularly admired her use of camera angles, discussing with a colleague how placing the camera below a subject’s eye height “gives him dominance,” making for a “hero shot.” He understood the power of the visual and how it could overleap rational thought and bury itself in a viewer’s gut.

When he was setting up Fox News, he recruited one of his early bosses from his time on a daytime chat program, The Mike Douglas Show, Chet Collier, who would say, “Viewers don’t want to be informed; they want to feel informed.” By now it was 1996, and Ailes and Murdoch had executed a piece of “messaging jujitsu” by giving their new service the slogans “Fair and Balanced” and “We Report, You Decide.” However much the content on Fox News has been shown to be anything but fair and balanced, it remains true that the slogans tapped into a scepticism, even a hostility, towards the mainstream media.

That scepticism has something to do with the fact that the bulk of journalists and editors hold more progressive or “liberal” political views than many of their compatriots, but it also reflects audiences’ intuition that the news media is never as objective as it likes to say it is. This is only partly a product of the gap between journalists’ reporting and their personal beliefs. Mainly it’s a result of trying to pretend that the messy and rushed process of news gathering, especially for complicated and contested issues, can be smoothed away and the news presented objectively by “voice of God” news presenters.

“Ailes had proclaimed to the New York Times that television was ‘the most powerful force in the world,’” writes Sherman. “And yet the network’s slogan was built on the premise that ‘it was up to you to decide if we’re fakers or if we’re telling the truth,’ as Messer [one of the ad men who came up with the ‘We Report, You Decide’ slogan] said. What Ailes was selling, at its heart, was not news, but empowerment. Fox was putting forth the notion that its audience could come to their own conclusions, while ‘feeling informed.’”

Over the next two decades, having performed this twist, Ailes proceeded to junk long-held standards of journalism and use his network primarily as a propaganda vehicle.

Initially, Fox was staunchly behind the Republican Party, which primarily took the form of tearing down the Democrat presidency of Bill Clinton. When the story broke in 1998 about an affair between Clinton and White House intern Monica Lewinsky, Ailes immediately set up a new evening program called Special Report and assigned five producers and correspondents to cover every aspect of special prosecutor Kenneth Starr’s investigation of the affair.

When the al Qaeda terrorist attacks occurred on 9/11, Fox outdid all its competitors in its belligerent patriotism and its denunciation of anyone questioning either the link between the attacks and Saddam Hussein or the need to invade Iraq.

During the 2004 presidential campaign, Fox gave extensive, uncritical airtime to the so-called Swift boat controversy. As Sherman notes, where the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal at least had at its core a real story, the Swift allegations began as a campaign commercial that sparked a “cable-ready controversy over what the underlying facts might be.” The key point is that the controversy rather than the story became the prime driver.

By the mid 2000s, Fox had become a “perpetual conflict machine” that had fans rather than viewers. As Sherman notes, by 2009 its audience was more than double that of its cable rivals, CNN and MSNBC, and by 2016 it was earning US$1 billion annually, accounting for a fifth of 21st Century Fox’s annual profits.

Ailes began to experience delusions of grandeur, signing up to commentary positions five of the prospective Republican Party presidential nominees for the 2012 election and proclaiming that, though profits were strong, “I want to elect the next president.” But when the Republican Party leadership didn’t do what Ailes wished, Fox turned to increasingly extreme right-wing political movements such as the Tea Party, whose influence was fanned, if not impelled, by the network.

After the disappointing performance of Republican candidate Mitt Romney in the 2012 election, and with another four years of Democratic president Barack Obama in prospect, Fox News’s ratings and influence began to dip. At the same time, social media was becoming more and more important. It was a communication channel that bypassed mainstream media and so reduced its profitability. It was also a potent mechanism for fanning not just the controversies baked into Fox’s modus operandi but also wilder, even unhinged, conspiracy theories.

Ailes didn’t want to invest in new technology, such as touchscreens and holograms, believing that his viewers, predominantly older white males, preferred the simplicity of a traditional television newscast.

Then, of course, came the ascendancy of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential campaign. The two men have been friends, and both have trafficked successfully in exploiting people’s fears. But Ailes was forced to leave Fox News just hours before Trump accepted the Republican Party presidential nomination in July.

Sherman reported in October that Ailes had briefly offered Trump advice during his preparation for the presidential debates. But since then, Ailes has not featured publicly in stories about Trump’s transition team and has largely faded from view. Now, as the world awaits the full impact of a Trump presidency and new words such as “alt-right” and “post-truth” are respectively being short-listed for and winning the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year, it is important to remember, as Jelani Cobb wrote recently in the New Yorker, that we should really call out these shiny lexical baubles for what they are: fascism and propaganda.

There is much to be fearful of in a media world that has been so profoundly marked by the likes of Roger Ailes, but it shouldn’t be forgotten that his demise was spurred by old-fashioned shoe-leather reporting. Sherman interviewed 614 people for his book and employed two fact-checkers, Cynthia Cotts and Rob Liguori, who between them spent 2098 hours vetting his manuscript for “accuracy and context.” The endnotes come to ninety-eight pages. Since the book’s publication, Sherman has written a further thirty-three articles for New York magazine about Ailes’s travails.

Ailes and his entourage did everything they could to smear Sherman. He was called a “phoney journalist” – by Fox presenter Sean Hannity, of all people. Breitbart devoted 9250 words to denigrating him, including quoting an anonymous Fox source who described him as “Jayson Blair on steroids” – a reference to the disgraced former New York Times journalist who fabricated articles and abused drugs (and evidence, if it were needed, that those at Fox have undergone total ironyectomies).

The smear campaign didn’t work. There are all sorts of reasons for Ailes’s demise – not least Rupert Murdoch’s gradually loosening grip on corporate power and the rising influence of his two sons, who both loathe Ailes. But the adherence in Gabriel Sherman’s work to facts and to fairness – he gave Ailes many opportunities to present his version of events – is a much-needed reminder of long-established journalistic virtues and cause for at least some optimism in what was, as I noted at the outset, a very ugly year. •