The Worst Woman in Sydney: The Life and Crimes of Kate Leigh

By Leigh Straw | NewSouth | $29.99

The doors of Tilley’s Devine – the cafe established by Pauline Higgisson, a single mother of two, with funds from a federal community employment scheme – opened in the Canberra suburb of Lyneham in the spring of 1984. Thirty-two years later, Tilley’s is one of the capital’s most treasured landmarks, long the venue for gigs by musicians of local and international standing, and still a bar with a certain cachet. It’s hard to believe, entering it now, that its beginnings were so bedevilled by vilification and controversy.

It would be easy to assume that the controversy arose over the choice of name. Tilly Devine was one of two legendary Sydney crime bosses distinguished by the fact of their sex. The other, Kate Leigh, is the subject of this new biography. Between them, from the 1920s to the 1940s, these women controlled most of the sly grog, cocaine and prostitution rackets in Australia’s harbour city; in fact, given their shared history, the Canberra cafe might just as well have been named for Kate. In the eyes of decent society, they were both bad women, and very clever to boot, and which of them was the worst was the source of endless speculation.

The controversy in Canberra, though, was not about Tilly Devine’s reputation. It centred on the stipulation that the cafe was for women. A man was not allowed on the premises unless he was accompanied by a woman. Tilley’s was the quintessential feminist project; the tables, so to speak, were turned. After decades of being banned from public bars unless escorted by men, we women had a place of our own. The problem was that it was funded by taxpayers’ money, and many men complained. Eventually they were allowed to come on their own. Despite the concession, the venue was long the centre of Canberra’s lesbian subculture, especially on Friday nights.

Feminism in the 1980s was a complicated matter, as it is now. The fact that Tilly Devine made her fortune running brothels and certainly showed no pronounced antipathy towards men didn’t seem to sully our admiration for her, in spite of our conflicted stand on prostitution. Draped in furs and dripping with diamonds, she willingly used the feminine wiles that we feminists emphatically rejected. Nothing she did improved the status of women; indeed, it could be argued that she made the lives of many worse. So was she a role model? Was it really because Tilly – like Kate, her rival – was successful in a field where men dominated? Could it have been that trivial? Or was it about something more?

With women like these, I’m suggesting, we are entering the realm of archetypes. By our very nature, feminists are transgressive, at least in the patriarchal order of things. It doesn’t matter how we dress, whether or not we are beautiful or comely, our very being disturbs. It’s true that if men shared their power with women, if there were less segregation of genders into separate spheres of activity, then men as well as women would benefit. The world would be a better place for it, for feminism is a movement about justice. But as long as there’s a fight on our hands, we will disrupt things and be deemed ugly, even bad. Go ask Julia Gillard or Hillary Clinton. So a feeling bursts out now and again that if we’re going to be seen as bitches or witches, we may as well have the fun that goes with it. And even when women are as meek as we’re supposed to be, there’s a fascination there, all the greater perhaps because we’ve been conforming.

All this is speculative, of course, and this is where the biographer comes in, to land us on solid ground. Leigh Straw has set herself the task, and it hasn’t been easy. For all their notoriety, and the fact that their stories are strewn through a variety of sources, neither Tilly Devine nor Kate Leigh has ever been honoured with a book-length biography before, possibly because of problems I’ll come to.

But first, here are the bones of Kate Leigh’s story, as laid out in The Worst Woman in Sydney. Born Kathleen Beehan in Dubbo in 1887, Leigh was eighth in a family of ten children. Her father Jack was a boot- and shoemaker, her mother Charlotte worked at home (and with a family of ten to look after, worked very hard). The family was poor, as many were at that time, and like most kids in poor neighbourhoods, urban or rural, Kate spent her days playing in the street and looking after her two younger brothers. Her wildness soon came to the attention of the local police, though, and at sixteen she was sent, with her parents’ blessing, to the recently opened industrial school for girls in Parramatta, 400 kilometres from home.

Straw, a historian, is very good at setting the scene for each stage of her subject’s life. The industrial school was merely the latest iteration of the infamous Parramatta Female Factory, established soon after white settlement to house the most refractory of the female convicts. It was a miserable place where inmates were routinely abused (until it was closed in 1974), and Kate spent her time there being prepped for domestic service. Although she couldn’t wait to turn eighteen and be released, as Straw observes, “It was the perfect kind of training for the life that awaited her in the working-class slums of eastern Sydney.”

Not long after her release, she met a petty crook and opium addict named Jimmy Lee and bore their child, a daughter, Eileen. Jimmy and Kate married two years later, but eight years after that he absconded, and Kate was left to fend for her daughter and herself. (To remove the stigma of his Chinese name, she changed it to Leigh.) Alone and poor, with no family support, she gravitated to Darlinghurst and then Surry Hills, where over the years she would come to be known as Queen of the Hills or, even more affectionately, simply Mum. This, despite the empire she built running a string of sly-grog shops – the biggest boost to her fortune coming, of course, from the state government’s imposition of the dumbcluck six o’clock closing time for pubs, which created the six o’clock swill.

Leigh came into her own in the 1920s, when she cornered the market in cocaine. In business parlance, she had diversified, making her money now from drugs and prostitution as well as sly grog. Both Leigh and Devine were prominent figures during Sydney’s horrific razor wars (described in Larry Writer’s Razor: Tilly Devine, Kate Leigh and the Razor Gangs and, more or less accurately, in the TV series Underbelly Razor). But, unlike Devine, Leigh prided herself on never being charged with prostitution and abstaining from liquor and drugs. She was imprisoned several times, was not afraid to use a gun and did kill a man, though she claimed it was self-defence. She married three times but, unsurprisingly, none of the marriages stuck.

By the 1950s, in her seventies, Leigh had become a matriarch of her community, the model for Delie Stock in Ruth Park’s Harp in the South. She was beloved for her acts of charity, including providing bail for first offenders to keep them from lives of crime, and hosting annual Christmas parties for the Surry Hills children. In stark contrast to Devine, who moved to seaside Maroubra when she could afford to, Leigh stuck with her working-class suburb, and when she died she was mourned. By then, in 1964, both she and Devine had already lost control of the crime scene to newcomers like Abe Saffron. An era had truly ended.

For all the fascination in Leigh’s story, Straw has been hobbled in piecing it together. The problem lies with the sources. Leigh, like Devine, was a consummate self-promoter and had ongoing, sometimes stormy relations with the press, which no doubt coloured the reporting. Yet other sources were hard to come by. Leigh wrote few letters and never kept a journal; her profession necessitated a degree of secrecy, never mind her limited education. There are the police records but they are sparse; Leigh was adept at keeping clear of the law. So while all biographies require a degree of imagination, hers would demand more than most.

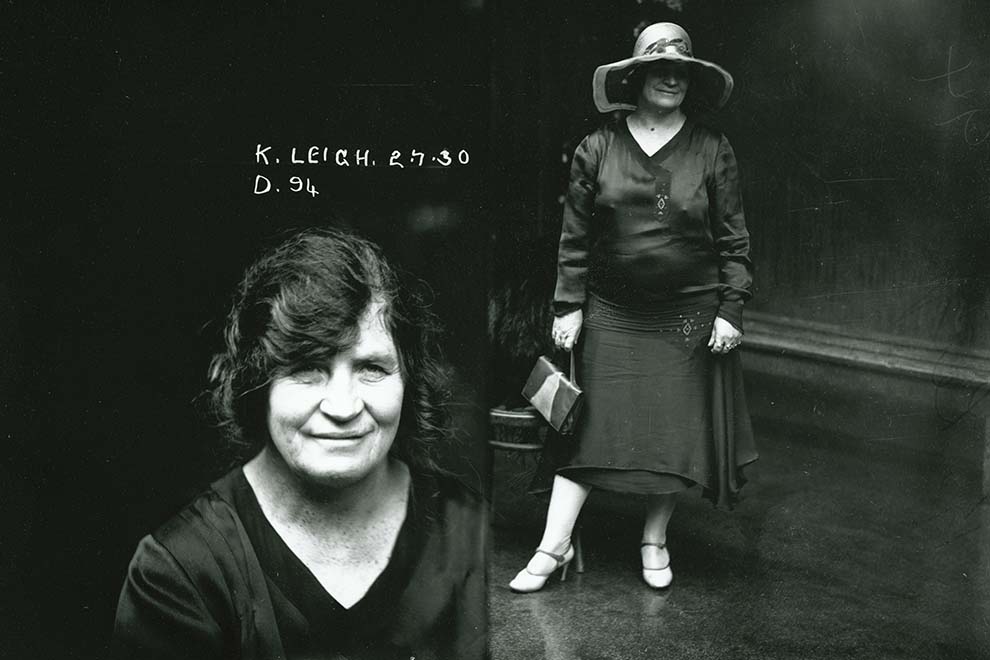

Straw deals with this in not always satisfactory ways. The structure is ordered thematically instead of chronologically, and this works well, each theme adding successively to the reader’s familiarity with the subject. But it also leads to repetition, some of which can seem like padding. And Leigh herself remains a somewhat elusive figure (though a lot can be gained from her photos). To compensate, Straw intersperses the text with short, fictionalised chapters – a ploy that takes tremendous skill to pull off, and when it succeeds, raises the question: why not a novel?

Was Kate Leigh a bad woman, the worst in Sydney? Straw finds it necessary to keep reminding us that she was. But despite the biography’s shortcomings, she has succeeded in presenting us with a character who’s more good than evil – a woman who is the product of an impoverishment difficult for us to imagine, who had the grit to overcome it, and who repaid with loyalty the community that supported her.

Sydney’s Surry Hills would be unrecognisable to Kate Leigh, were she alive today. The irony is that it is only as a result of its remarkable gentrification that Leigh has finally received her due. On 10 March 2012, twenty-eight years after the launch of Canberra’s Tilley’s and forty-eight years after Leigh’s death, the cafe Sly was opened at 212 Devonshire Street, one of her homes and grog shops. About time, I say. For reasons complex and conflicted, we do love our bad women – not least because through them we recognise the bad lurking in ourselves. •