Windsor’s Way

By Tony Windsor | Melbourne University Press | $32.99

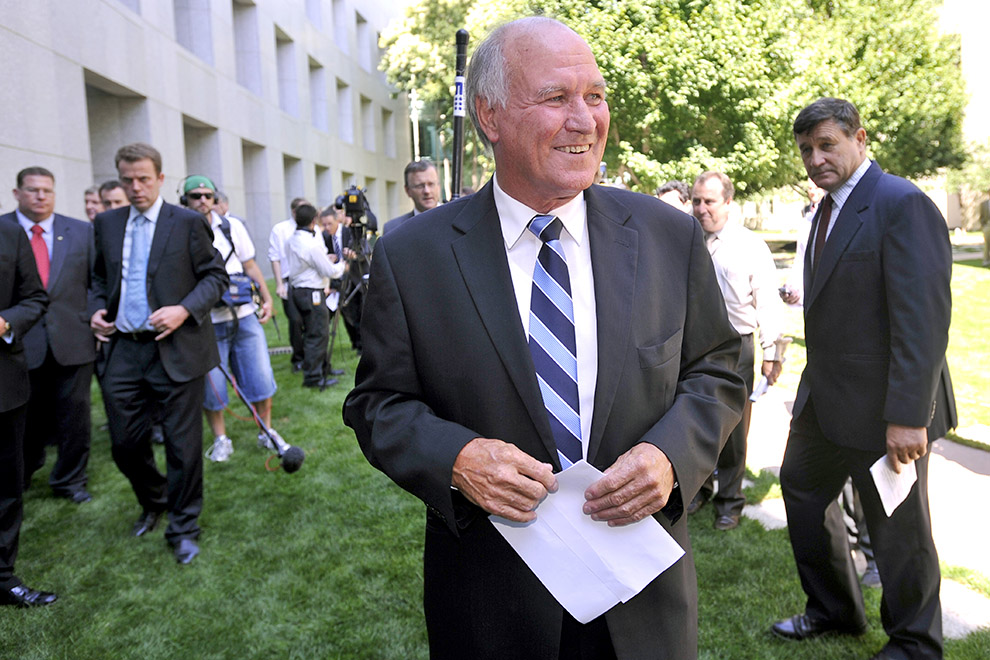

A funny thing happened to Tony Windsor on his way to reclaiming the seat of New England at the 2010 election. His political opponents wanted to congratulate him.

Normally no one from the big parties ever rings on election night to congratulate an independent MP. But that year, not long after Windsor had appeared on television to claim victory in his seat for an impressive fourth time, Joe Hockey left a message on his voicemail.

Later in the evening, prime minister Julia Gillard called up to wish him well. And even later, in the wee small hours, opposition leader Tony Abbott called up for a quick chat.

So why were all the big party bigwigs phoning this relatively obscure rural MP? Well, as everyone in the country from Antony Green down could see at the time, the forty-third federal parliament was heading towards a tight finish. So tight, in fact, that it was just possible Windsor was on the cusp of becoming a very powerful player indeed.

Over the course of the following week the counting went on. Then, in short order, Adam Bandt won the seat of Melbourne for the Greens and declared for Labor; and Tony Crook, a Western Australian National, but not a Coalitionist, ousted the Liberal’s Wilson Tuckey in the seat of O’Connor and threw his support behind Tony Abbott. In a 150-seat parliament it was now a seventy-three-all tie between Labor and the Coalition.

Just four independents were left to decide who would govern the country for the next three years: former intelligence analyst Andrew Wilkie, the member for Denison in Tasmania; the eccentric former National Bob Katter in the Queensland seat of Kennedy; the voluble former National Rob Oakeshott in the NSW seat of Lyne; and, of course, Windsor.

Wilkie soon announced he’d cut a deal with Labor on poker machine reform, and then there were three. Australia now entered a glorious seventeen days of political limbo while the remaining independents came to their decision on who would get their support to form a minority government.

Other democracies do this all the time – and with a lot less fuss and media outcry than Australia managed in 2010. Denmark, for example, hasn’t had a majority government for over a century, and it’s clearly one of the best-run countries on earth.

Eventually, Katter stuck with his roots and backed Abbott; not long after, Windsor and Oakeshott bravely went with Gillard.

The Great Experiment in Minority Government had begun – except it wasn’t really that much of an experiment at all. We’d had a federal minority government once before – back in the 1940s – and what was occurring now was really just the smooth whirring of the constitution as it clicked into place. But try telling that to an overexcited media and a citizenry with little sense of history and even less knowledge about how their nation is governed.

So how did Windsor arrive at his momentous and – in some quarters – unexpected decision? Like most things in politics, it was a mixture of policy and the personal.

One of the reasons Windsor entered politics in the first place was his belief that rural Australians had been shortchanged by the Australian political system. He’s consistently said throughout his twenty-year political career that “with 30 per cent of the vote, country Australia has the potential to have the balance of power – irrespective of who is in power… – and influence the political process far more than it has in the past.”

If Windsor was going to get an opportunity to be a kingmaker, the new king – whoever it turned out to be – was going to have to deliver for rural Australia. For Windsor, delivering for the Bush meant getting the National Broadband Network up and running, acquiring a seat for himself at the table when the Murray–Darling was discussed, and making sure of a commitment to fighting climate change via a carbon price.

But most importantly, Windsor wanted to go with the side that was most likely to deliver a stable, workable parliament that lasted the full three years. To do that, he would have to judge the leadership qualities of Tony Abbott and Julia Gillard. And so, at the heart of this fascinating behind-the-scenes political memoir, is the story of Windsor’s relationship with these two leaders.

It’s pretty clear that Windsor didn’t much like Abbott at the beginning of the process. And that after seventeen days of negotiating with him, he didn’t much respect or trust him either.

He realised pretty early that Abbott’s bullying, rugby-forward style of politics was never going to work in a minority government. He was also concerned that Abbott’s flaws would become more apparent once in office. As he famously told parliament, Abbott had literally begged for the job of prime minister, “and the only codicil [he] put on that was: ‘I will do anything, Tony, to get this job; the only thing I wouldn’t do is sell my arse.’”

It is equally clear from Windsor’s Way that its author admires Julia Gillard immensely. She was calm, honest and ready to negotiate. At some political cost, he went with her, and she delivered for him.

To some extent, how history judges Tony Windsor will depend on how it judges Australia’s last three prime ministers, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott. Because Windsor chose Gillard over Abbott and acted as a very effective Praetorian Guard in her defence against Rudd – as he was always quick to point out, the deal to allow Labor to form a minority government was with Gillard, not Rudd – their names will be forever linked.

But that is not to play down Windsor’s own achievements. His was a rare voice in Australian politics: vernacular, unprocessed by spin, and truth telling. He writes this, for example, about the major parties and their dissembling habits:

They just bullshit their way through the election campaign and then suddenly they find something’s not quite right when they’re in office, something they claim they didn’t know and couldn’t have taken into account when doing their sums.

His enemies in parliament and the media – chiefly News Corp – must have celebrated when he chose not to contest New England for the fifth time at the 2013 election. But unfortunately for them, the Windsor legacy looks like living on.

As another new book, Minority Policy: Rethinking Governance when Parliament Matters, written by two former advisers to minority politicians ably demonstrates, the continued existence and growth of small parties and independents has the potential to revolutionise Australian politics. Brenton Prosser used to work for Senator Nick Xenophon and Richard Denniss was an adviser to both the Democrats’ Natasha Stott Despoja and Bob Brown of the Greens. They predict a bright future for any budding Tony Windsors out there.

And if the man himself is to be believed, he might be back himself one day. As he says towards the end of this engaging and informative memoir, “Now that I am refreshed and still interested and concerned about where our nation is heading I would not rule out a return to politics… Watch this space.”

Could we see a new Windsor campaign sometime soon, with a launch hosted by a certain redheaded former PM? •