Twenty years ago today, Jeff Kennett’s Liberal premiership of Victoria came to an end. He had led the Garden State’s most radical government for at least a generation, privatising major state utilities, cutting chunks out of the public service and shrinking social spending. Schools across the state had been shuttered, huge new infrastructure projects launched in inner Melbourne, open-slather development encouraged in the suburbs. The state’s political economy had been rearranged to the extent that some academics asked if a revolution had taken place.

When he was elected seven years earlier, in 1992, Kennett had inherited a state hit hard by Paul Keating’s “recession we had to have.” Government debt had gone through the ceiling, unemployment had spiked, a state-owned bank and a major building society had collapsed, the population was shrinking and all manner of services had been crippled by rolling industrial action. Though Kennett dealt with these crises with brutality and even callousness, and though many of his cures would later be seen as worse than the disease, Victoria had performed a remarkable recovery by 1999.

We might expect the electorate to reward the party presiding over such a recovery, regardless of how it had come about. That certainly seems to have been what the Liberals were banking on ahead of that year’s election. But despite the expectation of an effortless win, Victorians took the opportunity to dispatch Kennett and replace him with Labor’s Steve Bracks.

It’s easy to forget just how surprising that result was. Bracks went on to be an incredibly popular premier, retiring well before the electorate had the chance to turn sour on him. The Labor Party still wheels him out when it is feeling nervous — as it was before the 2012 Melbourne by-election, for instance. So it’s tempting to regard his rise as somehow inevitable. Of course his low-key approach was more attractive than Kennett’s combative style; of course people felt bruised and weary after six years of relentless reform; of course rural Victoria felt neglected and was ready to shift allegiance.

But it wasn’t “time” in Victoria in the sense that it had been time for Labor’s Gough Whitlam in 1972. Indeed, Bracks’s victory over Kennett very nearly didn’t happen; on election night, and on the night after, and for four whole weeks following polling day on 18 September 1999, it wasn’t clear who would lead the state into the new millennium. For a full month, Victorians had no idea whether the state was taking a breath before plunging into another few years of Kennett-era hyperactivity, or whether respite was coming with the more cautious, easygoing, no-surprises Bracks.

Kennett had been soaring in the opinion polls before the election — so much so that Labor decided there was little mileage in attacking him personally — and the Coalition had a healthy margin of thirteen seats in an eighty-eight-seat chamber. Channel Nine was so sure the election would be boring it decided to wrap its election night coverage around its Rugby League broadcast. (Sure, the Melbourne Storm were in the preliminaries for the first time, but still, this was footy-mad Victoria.) Journalist George Megalogenis reported that Bracks’s reaction to a poll in the Australian predicting a cliff-hanger result was a suspicion that “the Australian is on drugs.”

Quite early in the evening, though, it was clear something had gone wrong for the Coalition. Voters had swung against the government, particularly in regional towns, to a totally unexpected degree: by 7.2 per cent in Ripon, by 8.1 per cent in Bendigo East, by 9.4 per cent in Gisborne. Labor’s targeting of the regions had been much more successful than even it had anticipated. (“Victoria has a new Country Party,” said political scientist Brian Costar on ABC radio that night, “and its name is the Labor Party.”)

Even on the night, the future premier remained cautiously pessimistic, suggesting victory was many steps away yet. But across town, Kennett sounded remarkably like a man defeated. “I think the public has decided to return a Labor government,” he told supporters at the Hilton Hotel. “If that is the case I will accept that decision with grace and get on my white charger and ride into the sunset. In accepting responsibility I have always said they either love Kennett or they hate him. Looks as though the vast majority, or the majority, probably hate him.” The cream, as journalist Peter Coster remarked in the Herald Sun, had indeed been sucked out of the Kennett cowlick.

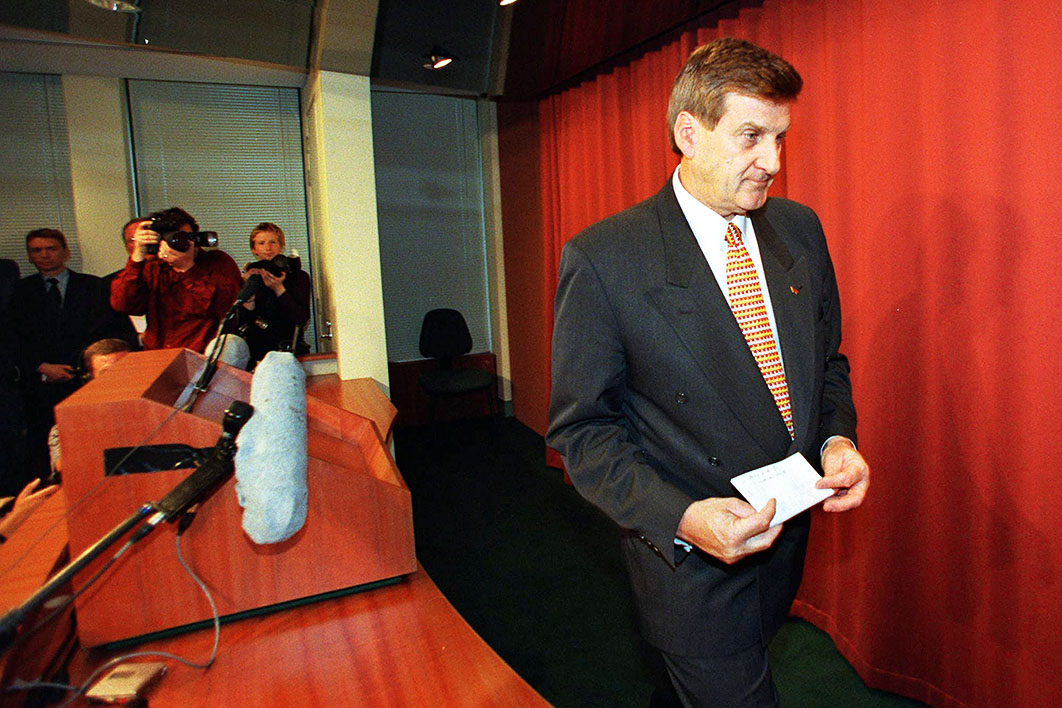

By next morning, though, it was apparent that the game was by no means over. At an impromptu press conference, Kennett said he was off the charger and back in his office, where he could see “a fair range of options… from a close Coalition win to a hung parliament to a Labor win.” The papers were reporting forty-two seats for the Coalition and forty-one for Labor, with forty-five needed for a clear majority. A clutch of seats remained too close to call: Mitcham and Carrum in the suburban southeast, Swan Hill up in the north, and Gippsland East.

And then there was Frankston East. On polling day, Trish McLellan, wife of the incumbent member, Peter McLellan, arrived at his unit to find her husband had died of a heart attack overnight. The fifty-six-year-old Liberal-turned-independent had been in high spirits on election eve: having managed to more than double his margin at the previous election, he felt he could capitalise on public antipathy towards Kennett now that he had gone independent in that close marginal seat. His death meant the electoral commission had to declare the Frankston East poll invalid, with a re-run to occur at a later date.

By the end of the week following the election, it seemed possible that Kennett could be back with a majority. An independent — abalone diver and first-time candidate Craig Ingram — had taken Gippsland East with a whopping 22 per cent swing, but the Nationals were edging ahead of another independent (and notorious Australian Rules ruckman), “Big Carl” Ditterich, in Swan Hill. What’s more, the count in Geelong, which had been in Labor’s column, had tightened tremendously: by the Friday, Labor’s Ian Trezise was just twenty votes ahead of Kennett’s housing minister, Ann Henderson.

If the Coalition could hang on to both Swan Hill and Geelong it would reach forty-four seats and push Labor back down to forty. With a win later in Frankston East, Kennett could grab a miracle majority; even if he lost that seat, Labor would find it impossible to form government without Geelong. With the full crossbench onside, Labor’s best-case scenario seemed to be forty-four seats apiece. That would almost certainly lead to a fresh election, at which voters who had wanted to register a protest vote rather than change the government would, Kennett assumed, come to their senses. It was, for a few days of close counting, a tantalising prospect for Liberals.

Overnight on Friday, though, Labor won Geelong. Trezise was ahead by sixteen votes, with only fifteen overseas ballots left to arrive, making it potentially a victory by just one vote. If the result survived a recount, the possibility of a Kennett majority was more or less foreclosed. Over the days that followed, Labor hung on to Mitcham and won Carrum, both by less than 400 votes.

And so the state’s political correspondents shifted their gaze to the three crossbenchers who might hold the fate of the state in their hands. To win, Labor would not only need the support of all three — it would also need to win the Frankston East re-run. Kennett needed just two of the crossbenchers — or one, if he could somehow wrangle Frankston back to his column. Those three independents — Susan Davies (Gippsland West) and Russell Savage (Mildura), both veterans, and first-timer Craig Ingram — exploited their newfound importance to the hilt by negotiating as a bloc with Kennett and Bracks.

On 25 September, as the Kangaroos walloped Carlton in the 1999 AFL grand final, the troika published a charter setting out their joint demands. The list included the reversal of some of Kennett’s most controversial policies, most notably his stripping away of powers of the state’s auditor-general, as well as a judicial inquiry into an ambulance services scandal and major reforms to the state’s upper house. Steve Bracks gave a more-or-less immediate in-principle thumbs up to the entire charter.

Kennett did not. Though he offered what can only be described as humiliating concessions through the first weeks of October — to deal with the ambulance scandal that had played out on his watch; to restore powers to the auditor-general; and to moderate his behaviour and be more consultative — he stopped short of accepting changes to the Legislative Council, offering only an inquiry. Constitutional reform was not something electors had been voting on during the recent campaign, he argued; there was no mandate for such a change. And he warned that, without the support of the Coalition, Labor could not reform the upper house — where the conservative side of politics held a strong majority — either.

In any case, it appears that Kennett never thought he could win over the entire bloc. His hopes rested on gaining the support of the two more conservative MPs in the group: Savage, the former police officer, and Ingram, the self-described conservative from a Nationals area. Susan Davies — a one-time Labor candidate who had described Kennett as a “bully” who needed to be stood up to — was never counted as likely to back Kennett.

The courting, especially of the politically inexperienced Ingram, grew more and more intense through October. Kennett, aided by Nationals leader Pat McNamara, promised to back Ingram’s wish for more water to be directed into the Snowy River. Bracks managed to get Ingram into a meeting with NSW premier Bob Carr, who had a key role to play in any Snowy deal. Although Carr made no promises, the access seemed to impress the as-yet-unsworn MP. Carr also released a letter from Kennett showing that not so long ago the Victorian premier had been less than enthusiastic about environmental flows for the Snowy.

All the while, anticipation built over the Frankston East re-run, scheduled for 16 October. To have a hope of forming a minority government, Labor had to win that Saturday. Its candidate, Matt Viney, a pollster for the party, pulled out all stops. He ploughed his own funds into a campaign video — an actual VHS tape to be delivered to every household in the district. The party dispatched a young Daniel Andrews from the state office to oversee the ground operations. Steve Bracks’s face appeared on billboards up and down the shopping strip — something the man himself seemed visibly squeamish about when he visited the seat, according to the Age’s Sandra McKay.

Jeff Kennett, meanwhile, promised a $39 million funding boost for Frankston Hospital. Members of Victoria Police’s 160-strong Force Response Unit were sent down to Frankston for high-visibility foot patrols, eliciting outrage not only from Labor but also from Police Association assistant secretary Paul Mullett, who told the Age that the timing was just a little too cute. Trish McLellan announced that, days before his death, her late husband Peter had endorsed the Liberal candidate, Cherie McLean, and a leaflet circulated quoting the freshly buried MP as saying, “If I don’t win I hope Cherie does.”

The desperation in both campaigns was palpable. The whole state was watching. Under normal circumstances, Frankston East was a fairly natural if marginal Labor seat — but no one knew how local voters would respond to having the casting vote on which party would form government.

And even if Frankston East went for Matt Viney and Labor, would it be enough to avert a fresh election? Some constitutional experts found themselves explaining to disbelieving reporters that the final decision — to accept a Labor minority government, or go to a fresh election — rested with the governor, Sir James Gobbo (a family name nowadays associated more with police misconduct). Would Sir James accept the crossbenchers’ written assurances that they would support Labor? Indeed, would he recognise the support of Craig Ingram, not yet a sworn-in MP? Or would he feel it was safer to reconvene parliament and have the question tested on the floor? If Kennett lost the seemingly inevitable no-confidence vote, might he advise the governor to dissolve parliament and call a fresh election, as per Westminster custom? Would the governor refuse that request and commission Bracks, or might he be tempted to turn back to the people? Just a month ahead of the 1999 national referendum on the republic, the fate of Victoria’s government looked like it might rest on the vagaries of vice-regal discretion.

In the end, of course, there was no last-minute constitutional skulduggery, no fresh election. Labor triumphed in Frankston East, Matt Viney winning a shade under 55 per cent of the two-party vote. The following day, Bracks’s chief aid, Tim Pallas, would fly east to Gippsland and then all the way north to Mildura to collect the signatures of all three independents on a memorandum of understanding to be presented to Gobbo as evidence of Labor’s majority support — evidence Government House would find satisfactory. After a full month of grasping for a political lifeline, Kennett would relent, resigning as premier and as leader of the Liberal Party.

Things very nearly didn’t turn out that way. Perhaps Kennett could have swung a fresh election — and perhaps, knowing how close things were, he could have run a winning campaign. Or, as Russell Savage later suggested, perhaps the Coalition could have retained government if Kennett had resigned the leadership; perhaps a different leader, with a more conciliatory style, could have won those three over.

Tiny quirks of fate — the small group of voters who decided the result in Geelong; one man’s weak heart in Frankston East; a former abalone diver’s interest in the Snowy River; the latitude afforded to a memorandum of understanding by the chap in Government House — turned out to be as important as the large swing in the mood of the electorate. Cunning, skill, good rhetoric, effective fundraising — all these things are vital in politics. But so too, it seems, is good luck. •

An editor’s error in the date of the Kennett government’s “demise” was corrected on 17 October 2019