THE history of bossa nova is uniquely unconventional. The blues, country & western, jazz, rock & roll: all these great American forms of popular music had lowly beginnings. Because they were lowly, we can’t be certain of how or when they came into being – their inventors were not the sort of people to write things down. The blues seems to have begun among black share croppers in the Mississippi delta; country & western music is the Americanisation of European folk music among poor, white rural communities across the southern states; the first jazz pianists practised in the back parlours of New Orleans brothels, and the first jazz combos played the cast-off instruments of Confederate marching bands (clarinet, trumpet and trombone), combining them with a rhythm section from the plantations (banjo, tea-chest bass, and washboard). Rock & roll fused all these. Not much privilege there, then. And in Europe, going right back to the Renaissance, all the great music and dance crazes had begun with the peasantry, even if they ended up at court.

Bossa nova was different. Middle-class and modernist, the music was rhythmically complex and the lyrics witty, sophisticated and optimistic. Also, from the outset, the “new trend” was design-conscious. And we have a precise starting date. It was 1958; boom time in Brazil. Six years later, as “The Girl from Ipanema” entered the US charts, there were tanks in the streets of Rio de Janeiro and bossa nova was finished.

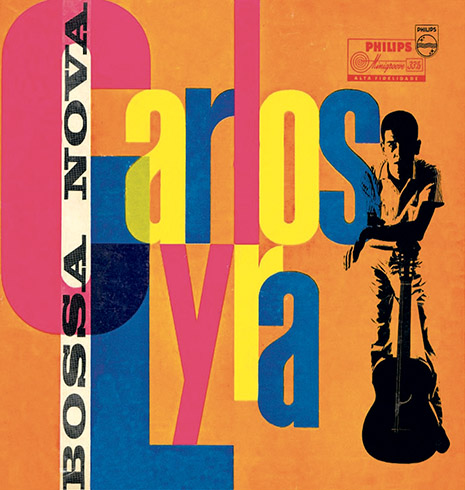

Bossa Nova and the Rise of Brazilian Music in the 1960s is the title of a startlingly handsome new volume “compiled” by Gilles Peterson and Stuart Baker. The shape, size and weight of a boxed set of LPs, it features the artwork for more than a hundred record covers along with a brief history of this highly infectious music. There is also a double-CD compilation going by the same title (though available separately), and this comes with its own seventy-page booklet.

In the early 1960s, most people outside Brazil got their bossa nova from Stan Getz, the West Coast purveyor of sultry tenor sax solos who, together with guitarist Charlie Byrd, released Jazz Samba to wide appreciation in 1962. Doubtless one reason for the record’s success was the very natural fit between the two styles of music, which is not surprising when one considers that the influence of cool West Coast jazz on Brazilian samba had produced bossa nova in the first place. But the reasons for its flowering were mostly political.

Brazilian politics in the middle of the twentieth century were dominated by the figure of Getúlio Vargas. He came to power in 1930, installed in the presidency by a military coup. A self-styled “father of the poor,” Vargas set about modernising his country, developing its industry and attempting to forge national unity through an Afro-Brazilian identity that involved promoting carnival and establishing samba as the national music. From this distance, it sounds like fun, but Vargas’s methods were repressive and fascistic. In 1934, he dismissed the parliament and ruled as dictator. Following his resignation in 1945, Brazil was returned to democracy and Vargas himself stood, successfully, for the presidency in 1951, a term that ended with his suicide three years later.

A succession of failed governments finally led to the election, in 1956, of Juscelino Kubitschek with the promise of “fifty years of progress in five,” and Oscar Niemeyer’s plans for the modernist jungle capital, Brasilia. Clearly they also needed a new music.

Poet, playwright and lyricist Vinicius de Moraes had also been a diplomat, his most recent posting in Paris putting him directly in touch with many of the newest ideas in contemporary theatre and philosophy, and indirectly with West Coast jazz. His 1956 play, Orfeu da Conceição (better known as the 1959 film, Black Orpheus), had set designs by Niemeyer and music by the pianist/composer Antônio Carlos Jobim.

Only one piece of the bossa nova jigsaw puzzle was missing. João Gilberto sang and played the guitar with a lightness of touch and sharply syncopated rhythmic sense that would become one of the musical style’s hallmarks, and he played on a new record featuring the songs of Vinicius and Jobim. One of these was “Chega de Saudade,” or “No More Blues.”

This was in 1958, the same year Brazil’s football team (starring the brilliant seventeen-year-old, Pelé) won the World Cup. National pride was at its zenith. You hear it in the music, which is confident, optimistic and cool. You also see it on the album covers, and while Peterson and Baker’s text might tell the story of bossa nova engagingly enough, it is this boldly sophisticated artwork that is the glory of the book. It is also the artwork that lets us appreciate how much of a moment in history bossa nova really was. If you want a retro coffee table, look no further. •