In 1874, as she embarked on her sixtieth year, the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron paused to write a brief account of her extraordinary, late-flowering career. “‘Mrs Cameron’s Photography,’” she began, referring to herself in the third person, is “now ten years old.” Her work has “passed the age of lisping and stammering and may speak for itself, having travelled over Europe, America and Australia, and met with a welcome which has given it confidence and power.” It is a wonderful introduction, eliding photographer and photographs in a way that reflects Cameron’s understanding of the complex relationship between the two. The photographs, she tells us, are Mrs Cameron’s; she made them and she is determined to get that clear from the very start. She speaks with the confidence of someone who has arrived — who has, along with her photographs, become something of an institution.

There is a further note of triumph in those first few words. They seem to contain a reference to her earlier critics, usually photographers themselves, of the kind who value details and accuracy and precision and were not at all impressed by someone who seemed unconcerned with any of these. For such critics, the phrase “Mrs Cameron’s Photography” would typically preface a condescending reference to her inexpert handling of light or focus, or to her very evident mistakes with the photographic process itself.

Julia Margaret Cameron was born in India in 1815 and educated in France and England. In 1834 she returned to India and four years later married Charles Hay Cameron, who was employed in the Law Commission in Calcutta. Hay Cameron, who was twenty years his wife’s senior, retired in 1848 and the couple returned with their children to England. There, they were immediately introduced to the literary circle surrounding Julia Margaret’s sister Sara and her husband, and to luminaries such as Browning, Darwin, Tennyson and George Frederic Watts. Cameron was thus both outsider and insider, brought up mostly abroad but rapidly absorbed, in her early thirties, into London’s most exalted literary and artistic circles, an aristocracy of intellectual and creative endeavour.

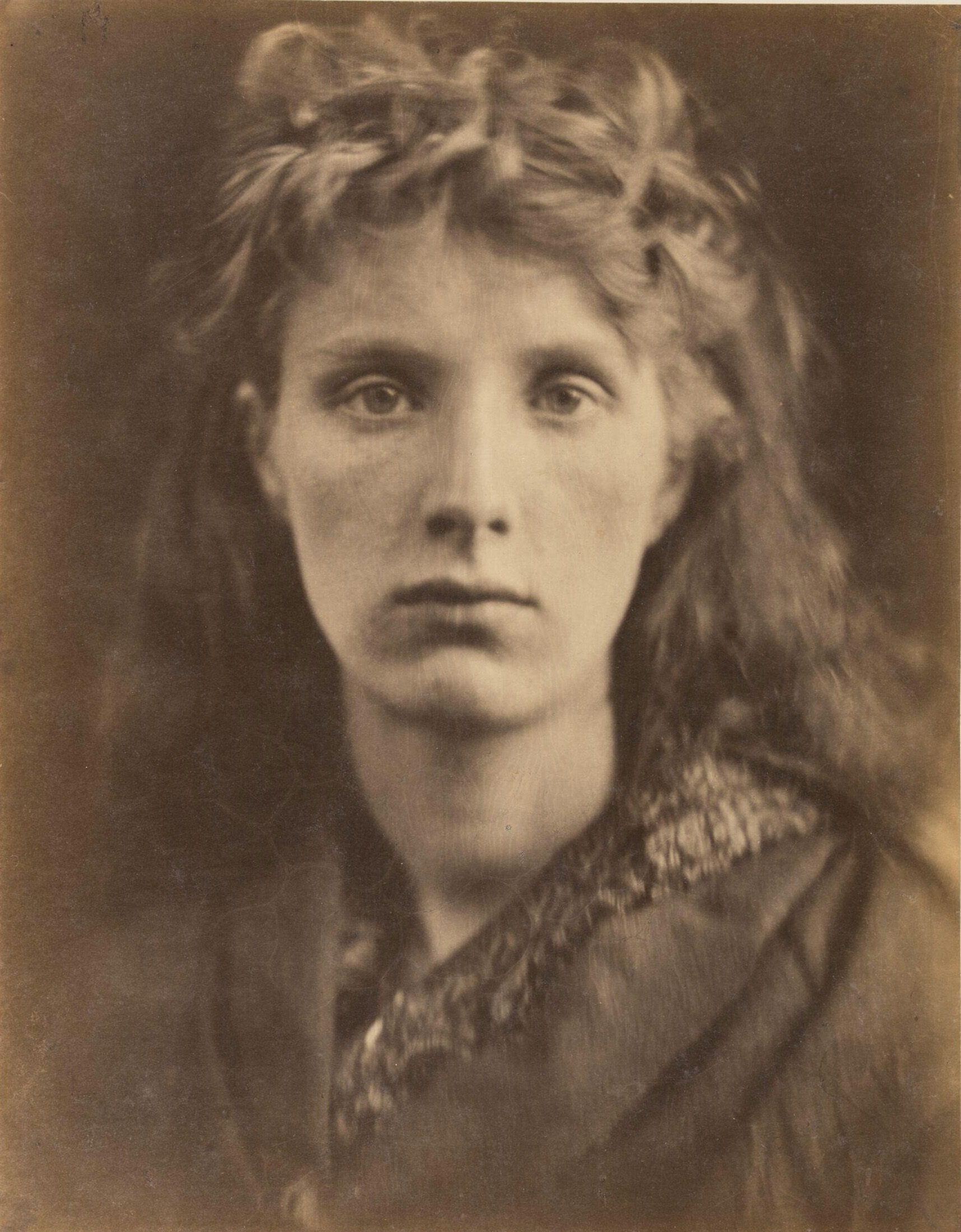

Cameron’s The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty (1866). Victoria and Albert Museum

Cameron exploited her connections to become one of the first celebrity photographers. But she also subverted notions of celebrity and entitlement by choosing housemaids and porters as her models, demonstrating that nobility of face and bearing were not necessarily confined to a particular social class. “Boatmen were turned into King Arthur,” her grand-niece, Virginia Woolf, remarked, and “village girls into Queen Guenevere.” Order was inverted in the interests of the image. “The parlourmaid sat for her portrait,” added Woolf, “and the guest had to answer the bell.”

When Cameron wrote that the viewing public had validated her work – had given it confidence and power – the “it” is clearly intended also to be read as “me.” Julia Margaret Cameron certainly acquired greater confidence – in herself and her technique – as her career progressed, but she seems to have started out with a fair measure too. From the very beginning she was able to rise above her literal-minded critics, partly because of her own innate determination and strength of character but partly too because she had the backing of those prepared to see the new medium as capable of producing art rather than being solely an instrument of record. In the same article, Cameron refers to photography quite simply as “the art,” but as to where the artistic impulse resided she was never exactly clear. Sometimes it seemed to come from her, sometimes from the camera – “it has become to me as a living thing,” she famously said of that cumbersome instrument – and sometimes from happenstance.

Cameron was fond of playing up the role of accident in the making of her photographs, sometimes telling stories against herself, of overexposures and smudges and scratches on the negative image, of printing the wrong way round and inadvertently coming up with something better, more evocative and more alive than the unsmudged, unscratched, right-way-round “original.” She recalled accidentally effacing her first attempt at a portrait “by rubbing my hand over the filmy side of the glass.” Just as Julia Margaret Cameron continues to give inspiration to late starters everywhere – she began her career at the age of forty-eight, after receiving her first camera as a gift from her daughter and son-in-law – so she continues to inspire the less technically assured of photographers by her demonstration of how it is possible to make a gloriously successful photograph without knowing, quite, how to make a photograph.

With this rather casual approach to the details of photography, Cameron was also deflecting attention away from technical matters, away from the importance of predetermined process, in favour of highlighting the role of chance in abetting the artistic eye. She gave due acknowledgement to chance because she understood, in a deeply instinctive way, that it is the very stuff of creativity.

In her catalogue of the exhibition of Cameron’s work showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Julia Margaret Cameron from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, curator Marta Weiss makes clear that where Cameron’s photographic practice is concerned, there are accidents and there are accidents.

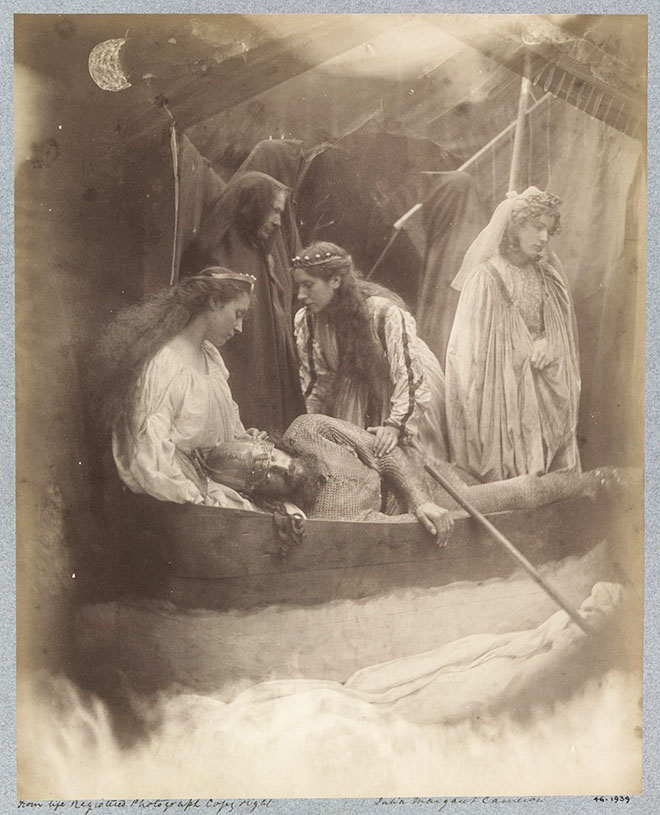

In a letter of 1869, Cameron expressed concern “about the problem of the ‘honey comb crack’” that had appeared on certain of her negatives and was, by a process “beyond any power to arrest,” relentlessly compromising them. Weiss points out that the cracks are visible in two images included in the exhibition, The Guardian Angel and The Dream, while noting drily that in the case of The Dream, Cameron, although “distraught by the cracking that befell the surface of the negative… seemed not to be bothered by the two smudged fingerprints in the lower right, which form a kind of inadvertent signature.” But Cameron’s interventions could also be deliberate: as an example, Weiss draws the viewer’s attention to So Like a Shatter’d Column Lay the King (below), one of Cameron’s illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, in which the photographer has stepped into the development process and scratched a moon onto the negative.

Cameron’s So Like a Shatter’d Column Lay the King, from a series of illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, taken in 1975. Victoria and Albert Museum

It is this interplay of chance and deliberation – did she mean it or didn’t she? – that helps to give Cameron’s photographs their power and depth. In her portraits and studies and tableaux, her subjects are posed and lit to emphasise stillness and continuity, dressed in costumes that evoke the past or in cloaks that evoke no particular time at all. We sense the director behind the camera, dictating the pose and the expression and keeping her subjects to their marks. The expressions are serene and contemplative, the eyes looking into the camera, or into the space to the right or left of the frame (Cameron returned often to profile studies – like that of Mary Hillier as Sappho, reproduced above), or downwards, as if to highlight the subject’s temporary withdrawal from the busyness of life.

In this sense, Cameron’s photographs seem to reject the bustle of the contemporary in favour of a dreamy, out-of-focus, semi-historical world where the women are beautiful and demure and the men are authoritatively thoughtful. And yet, with a combination of assertiveness and accuracy, Cameron would frequently annotate the printed image with the words “From the Life,” or variations on that phrase.

This quality of aliveness is what distinguishes Cameron from many of her contemporaries, and continues to underpin her reputation today as one of the greats. A photograph is inherently melancholy and backward-looking – it has been made in the past and it records the past. In a way, Cameron seems to embrace this quality in the way she poses and dresses and lights her subjects – almost invariably, they look pensive and vaguely sad. And yet we know they are acting, that these subjects have lives and preoccupations of their own, that they are not mere “subjects” but participants in a creative project. They are neighbours or nieces or friends of the photographer, elements in a network of connections that includes us as viewers.

Just as we know that actors have their own lives outside the play, so Cameron’s photographs remind us of lives outside the photograph. The very absence of accompanying visual detail concentrates the viewer’s attention on the face and the imagined life of the sitter, who has been captured in a moment of remission from that life, posing for the photographer and playing dress-ups. Cameron’s “mistakes” – the thumbprints and the smudges and the scratches – may have been accidental and may have been deliberate but either way they reinforce rather than detract from the overall impact of the images. (Marta Weiss quotes an early comment by the poet Coventry Patmore: “her mistakes were her successes.”) They contribute to the paradox that these formally composed photographs manage somehow to speak forcefully of the random exigencies of life.

Cameron’s Annie; ‘My First Success’, 1864. Victoria and Albert Museum

Cameron was ambivalent about crediting her actors. In what she called her “first perfect success,” Annie Philpot, the young ward of temporary neighbours of Cameron and her family, is pictured in a coat that seems a bit too large for her. She has the look of having been firmly buttoned into it, ready for her close-up. Her hair looks hastily and imperfectly brushed. (Cameron, like so many of the great portrait photographers, paid close attention to hair and headgear.) The light on the child’s hair and face is balanced by the glint of the second button on her coat. Annie and her coat dominate the frame; the background is a blur. The individuality of the girl is striking; it is a remarkable image, made all the more so by the knowledge that when Julia Margaret Cameron made it, in January of 1864, she had owned and operated her camera for less than a month.

In this sense, Cameron began as she was to continue; her early work includes some of her finest pictures, so much so that a mere year and a bit after she took up photography, the South Kensington Museum, predecessor of the V&A, purchased sixty-three of her images. That was in May of 1865, and was soon followed by the acquisition of a further seventeen a few months later and a further thirty-four a few months after that. Many of these images are included in the current exhibition.

Annie Philpot – the eternal child and “my best and fairest little sitter” – had a special place in the pantheon, a place which she retained, in Cameron’s eyes, throughout the ensuing years. Writing of Annie a decade later, Cameron went further. “I felt,” she recalled of that exciting day, “as if she had entirely made the picture.” Cameron seems here, if only for a moment, to relegate her own role to something analogous to the indifferent mechanism of her camera. But only for a moment. Weiss, in quoting this remark, goes on to balance it by referring to another assessment by Cameron of a favourite sitter, this time the dramatist and man of letters Sir Henry Taylor, who had also been a neighbour of the Camerons and with whom they remained lifelong friends. Sir Henry sat for over thirty portraits, evidently with patience and good humour. “He consented,” writes Cameron, “to be in turn Friar Laurence with Juliet, Prospero with Miranda, Ahasuerus with Queen Esther… and to do whatever I desired of him.” Virginia Woolf put it rather more astringently, describing Sir Henry, ever amenable to direction, as being habitually “covered in Tinsel.”

Sir Henry Taylor, a favourite sitter of Cameron’s, with Mary Ryan and Mary Kellaway in King Ahasuerus and Queen Esther, 1865. Victoria and Albert Museum

The American photography scholar Robin Kelsey devotes a chapter of his illuminating study, Photography and the Art of Chance, to Julia Margaret Cameron and her complex relationship to happenstance. In a world in which photography was becoming ever more regimented and rule-bound – “the mid-century portrait studio was engineered to subdue all forms of accident; head clamps and supporting stands limited unwanted bodily movement, and mirrors concentrated lighting to minimise obscuring shadows and permit sharp focus” – Cameron opened the image up to possibility, posing her clamp-free subjects for so long that they were bound to move, creating small shivers of vitality and aliveness in the final image.

Most persuasively of all, Kelsey identifies the central paradox of Cameron’s work, by which images of nostalgia and play-acting engender in the viewer, “despite the antimodern air of her sad madonnas,” feelings of hope for the future and confidence in the “irrepressibility of life.” Cameron seems to have anticipated, moreover, how crucial performance was to become as a way of negotiating modernity, how play-acting would increasingly be a means not of suppressing the self but of defining it. (Not that Cameron’s subjects always saw it that way; one child described her as a “benevolent tyrant” concerned only with extracting the best possible performance from her subjects.) Kelsey quotes a comment by the critic Janet Malcolm that will strike many viewers as true to the experience of looking at Cameron’s photographs: “we are always aware of the photograph’s doubleness – of each figure’s imaginary and real persona.”

Cameron was modern in other ways too, anticipating many of the characteristics and practices that were to be essential for a successful career in the new art of photography. She was relentlessly self-promoting, ensuring not only that the V&A would acquire examples of her output from early on in her career, but nudging, often quite hard, friends and acquaintances to praise her in public and preferably in print, thereby helping her to attract new clients and, even more importantly, enhance her reputation. She joined the Photographic Societies of London and Scotland to bolster her professional identity. She curated her own work, producing albums of her prints for presentation to friends and possible patrons.

Although she took pains to distinguish herself from the world of commercial photography, she understood the importance of endorsements, of competitions, and of having her work included in the international exhibitions that were held from time to time in various parts of the world – including in Australia, where photographs by Cameron could also be seen by visitors to Government House in Sydney. A guest in the 1870s, fortunate enough to get as far as the drawing room, would have been able to admire twenty or so of Cameron’s images belonging to the governor, Sir Hercules Robinson. Robinson also sat for Cameron; his portrait survives as a gold-bordered carte de visite, the miniature format that she was fond of using to advertise her wares.

Cameron understood the importance of copyright. The Copyright Act of 1862 had ensured that photographs were eligible for registration. “From May 1864 to October 1865,” Marta Weiss notes, “Cameron registered 508 photographs.” Even as her reputation, whether among her critics or her admirers, rested on her preparedness to overlook or simply bypass the “rules” of photography, when it came to asserting her rights as an artist, including her right to be identified, she was scrupulous in her attention to detail. When she wrote, on the day she completed her photograph of Annie Philpot, that she was her “best and fairest little sitter,” she also took time to note down the details of the image for posterity, and in the process unequivocally staked her claim to authorship. “This photograph,” she wrote, “was taken by me at 1pm January 29th Printed Toned – fixed and framed all by me and given as it now is by 8pm the same day Jan 29th 1864. Julia Margaret Cameron.”

Cameron may have occasionally left an inadvertent signature on her images – caused by her thumb, perhaps, or the brush of her clothing or her elbow against the plate – but she would also intentionally mark the plate to achieve a particular effect or, in at least one case, highlight her Madonna’s eyebrows with ink on the finished print. By her habit of intervention Cameron would in effect impress herself on the image, just as she would record her name on the plate or the print or the mount. In that sense, her signature was very advertent indeed. •

Julia Margaret Cameron from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2015

Julia Margaret Cameron: Photographs to Electrify You with Delight and Startle the World

By Marta Weiss | Victoria and Albert Museum | $55

Photography and the Art of Chance

By Robin Kelsey | Harvard University Press | $69