TO MANY people, the composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks’s greatest contributions to posterity might seem to be as benefactor and role model. When she died in 1990, she left her home in Sydney as a rent-free “haven” (her word) for mid-career composers. Since it opened, a succession of them have lived there, including Gordon Kerry, Julian Yu, Liza Lim, Elena Kats-Chernin, Matthew Hindson, Paul Stanhope and Mary Finsterer. I spent two years in the house from early 1998 to the start of 2000, and Julian Day will be the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Fellow for 2013, the residency now coming with $20,000 of spending money from the Australia Council.

As a female role model in a still male-dominated profession, Glanville-Hicks is equally significant. She would have bridled at the word “feminist,” but that’s what she was – strong-willed, quick-witted and sharp-tongued, she believed that women succeeded at composition by being better than men.

But how good was she? That’s the nagging question. This is the month of her centenary (she was born in Melbourne on 29 December 1912), and artists’ centenaries are, by convention, a time for assessing and reassessing reputations.

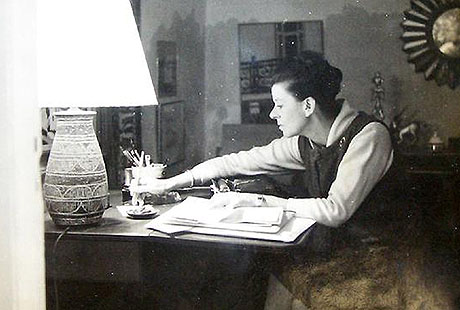

Biographically speaking, Peggy has always had a strong reputation – indeed she is one of two Australian composers known throughout the profession and routinely referred to by her first name alone. The other is Percy. Like Grainger, she had a colourful life, some details of which are better known than her music. She began her studies with Fritz Hart in Melbourne but left Australia in 1931 to pursue her vocation in Europe, first at the Royal College of Music in London, where she studied with Ralph Vaughan Williams, who liked her and recognised her talent, then in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. Following some early successes, including a performance of her Choral Suite conducted by Adrian Boult at a concert of the International Society for Contemporary Music, she sailed in 1941 for New York with her husband and fellow Boulanger pupil Stanley Bate. There, she found herself assistant to the composer–critic Virgil Thomson, writing reviews for the New York Herald Tribune.

The marriage didn’t last. Bate was not only homosexual, but was also filled with self-loathing and brimming with violence, the brunt of which Peggy bore. There followed a second failed marriage and a sequence of attractions and love affairs with other men, nearly all of whom were gay. They included the choreographer John Butler and the writer and composer Paul Bowles. Peggy’s female friends included Anaïs Nin. In 1958 she moved to Greece, where she felt she could live well, yet cheaply. In 1966, a brain tumour sent her suddenly blind, but after an epic operation to remove it, her sight returned. In exchange, however, she lost her sense of smell and her ability to compose. She returned to Australia in 1975, eventually buying the house in Ormond Street, Paddington, that is now the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Composers’ House. Although there was much talk and plenty of plans, there was no more music.

Still, by the time she stopped composing in 1966, she had produced a body of work that included instrumental and chamber music, orchestral works, concertos, songs and five operas in collaboration with the likes of Thomas Mann, Robert Graves and Lawrence Durrell. The Durrell opera, Sappho, was the last. Commissioned by the San Francisco Opera with Maria Callas in mind for the title role, the piano score was completed in 1963 but rejected by the company. Until recently, it had never been heard, but a new recording, out for Peggy’s centenary, puts that right. Conducted by Jennifer Condon, whose obsession with the piece secured an impressive cast and orchestra, funding, studio dates and the interest of a London-based record label, the double CD set crystallises many of one’s perceptions about Peggy’s work, its weaknesses as well as its strengths.

Stylistically, Peggy was her own woman. There is no one quite like her; she really did have a musical idiolect. One senses the influences of both her main teachers – Vaughan Williams’s modality, though taken to extreme, and Boulanger’s neoclassicism in the sometimes motoric rhythms and spiky textures – but she makes them her own and adds the influences of India, Indonesia and Greece. In the early 1960s, none of these attributes was meant to be a part of modern music (Peggy was both behind the times and ahead of her time), so one can picture Kurt Adler of the San Francisco Opera receiving the score, playing through the rather overblown rhetoric of the overture with its Aeolian modality, and hearing only the soundtrack to a dozen toga flicks. The fact that the composer of Sappho arrived at this sound by an entirely different route to, say, Dimitri Tiomkin, is neither here nor there.

But that is not to dismiss Sappho, merely to attempt to explain its rejection and subsequent neglect. There is so much good music in the piece that it is a great pity it has been dormant for fifty years, and a tragedy that Peggy heard it only in her imagination. The heroine’s final, emotional peroration – marvellously well sung by Deborah Polaski on this new recording – is a latter-day Liebestod.

Perhaps the key to Peggy’s art is that she was a miniaturist. (The same is true of Percy.) Sappho is certainly episodic – so is many a good opera – and Peggy’s entire output wildly uneven, but there are plenty of gems: individual movements and songs, and smaller works such as the harp sonata that Marshall McGuire has championed now for twenty years. In particular, there really is nothing quite like the wonderful Paul Bowles songs, Letters from Morocco, or the brightly sparkling Etruscan Concerto or the profoundly lyrical concerto for viola and chamber orchestra, Concerto romantico.

Of course, creating a personal voice is not the be-all and end-all of composing. Some very minor composers have succeeded in this. But neither is it to be sniffed at. And there is one quality in Peggy’s music that strikes me as very rare indeed. There is something about the music that makes you want to admire it. When you find you don’t, you are genuinely disappointed, but when you do – I am thinking, for example, of the third of those Letters from Morocco – you are transported somewhere unique. The words that Bowles wrote to Peggy in that very letter describe the experience quite well.

“There are concerts here – too beautiful to imagine – in the Dar Batha,” he wrote, “with fountains all splashing on the terraces, and the moon shining above the cypresses. I go, of course, and listen…” •