Don’t Mention the War: The Australian Defence Force, the Media and the Afghan Conflict

By Kevin Foster | Monash University Publishing | $24.95

LOTS of things weren’t mentioned in the public reporting of Australia’s longest war. Right to the end, terrible things were left unsaid.

Consider some of the things that happened around October last year, when Tony Abbott announced that most of Australia’s troops in Afghanistan would be home by Christmas after a twelve-year involvement that had ended, he said, in neither victory nor defeat, just the hope that maybe we had made things better.

Just two weeks earlier, ten Afghan police, eight insurgents and three civilians were reported killed in a district of Uruzgan province that Australian troops claimed to have helped liberate three years ago. The toll was equal to half the entire number of all Australian deaths in Afghanistan in twelve years. If their deaths rated a mention in the Australian news media, I missed it.

More Afghans were reported killed in Uruzgan in the following weeks, as Australian troops packed the last of their gear, leaving no trace that they and thousands of their comrades had passed through the sprawling multinational base at Tarin Kowt. The victims included a boy who rode his bike over a roadside explosive and three aid workers hit by a bomb.

In late November, Afghan media reported that three local polio awareness workers had been hanged by unknown killers in Uruzgan’s Chora district, a place familiar to hundreds of Australian soldiers. They didn’t seem to rate a mention in our media, either, even though Australian taxpayers have funded polio eradication programs in the province.

On 16 December, the day the Australian Defence Force, or ADF, announced that the last of our troops had left Tarin Kowt, four boys aged between six and eight were reported killed by a bomb planted in a place they used as a playground. Two days later, an Afghan policewoman and a female teacher were reported hanged and shot in Tarin Kowt district – the result of either a family feud or insurgent action, according to the media accounts, some of which were accompanied by gruesome pictures.

All of these deaths were reported by the Afghan media, in English, and some were picked up by international news agencies. Details, sometimes conflicting, were scant. Causes and context were missing. But it didn’t take any skill to find out more using Google. In the two months between Abbott’s announcement that the troops were finally coming home and the abandonment of Tarin Kowt, I counted thirty-six Afghan deaths in Uruzgan, most of them civilians – almost certainly an incomplete count. This means that at least as many Afghans died violent deaths in Uruzgan in those two months as Australians lost their lives during the entire war.

It’s a fact of life in traditional news reporting that deaths in distant, complex, foreign countries are less newsworthy than Australian losses anywhere. But even allowing for that cold calculus, the lack of Australian reporting of those Afghan deaths helps confirm what Kevin Foster, in his revealing book Don’t Mention the War, condemns as a “critical failure of coverage” that has left the public ignorant of the Afghan war and our role in it.

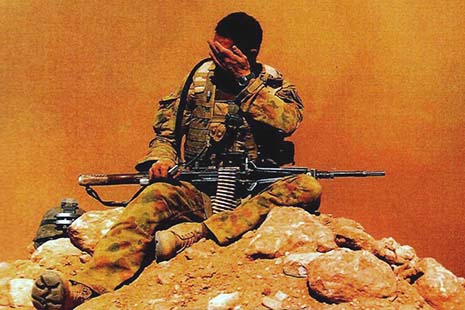

Apart from a tiny handful of extraordinary exceptions – the work of the ABC’s Sally Sara comes to mind – news reporting of Australia’s role in the war scarcely featured ordinary Afghans. As Foster puts it, the battle for their country mattered to the Australian media and the public “only in so far as it provide[d] a platform for deeds of valour and sacrifice that showcase [our] essential national qualities.” Even that level of interest was shallow, and the reporting of those deeds was often little more than a caricature.

Foster argues convincingly that the ADF’s determination to keep an iron grip on information, based on an entrenched cultural disdain for journalists, a resistance to scrutiny, and an obsession with protecting its reputation, meant that what it was actually doing in Afghanistan remained a mystery. While he attributes authorship of this mystery to the ADF hierarchy, supported at times by politicians, journalists don’t escape his censure. His book is an indictment of the lack of commitment by Australian editors to covering the Afghan war.

Foster, who teaches media and cultural studies at Monash University, traces how and why the ADF and the Department of Defence went out of their way to obstruct media coverage, and to what effect. He compares Australia’s attitude to independent scrutiny to that of our allies in Afghanistan, particularly the Dutch and Canadians, and finds Australia performed poorly on almost every count. Drawing on the historical record and his original research, Foster reaches a dispiriting and sobering conclusion: “The war in Afghanistan has not only been the nation’s longest military commitment, it has also been the worst-reported and least-understood conflict in Australian history.”

THE Australian military’s particular and virulent aversion to journalists and journalism has a long history, as old as the Anzac legend itself. The cameraman Neil Davis, who came across the Australian army’s obstruction in Vietnam, characterised it as “the feel free to fuck off” approach to public relations.

Given the role of journalists, from C.E.W. Bean onwards, as creators, scribes and acolytes of the Anzac legend, there is a dazzling irony here. The latest evidence, based on an army assessment of media coverage once reporters were finally given access to the troops in Afghanistan, suggests that many Australian journalists instinctively abandon detachment once they get close to our soldiers. Perhaps that’s why they call it embedding. Yet despite all that journalists have done for the army in helping it achieve a public position of “respect bordering on reverence,” Foster finds little evidence that the defence hierarchy understands the role of the media, let alone feels even a pinch of gratitude.

Instead, suspicion endures. Foster argues that the standoff was reinforced by the Vietnam war, after which the army acquired a misremembered “lesson” – that the American and Australian defeat was due to graphic and biased reporting that undermined popular support for the war.

Unlike the US military, the Australian army failed to unlearn this false lesson. In 2006, when Australian troops returned to Afghanistan in force, journalists were kept on a tight leash, restricted to brief, tightly scripted “bus trips.” Largely confined to the Tarin Kowt base, rarely venturing “outside the wire,” they were exposed to what even their army minders admitted were little more than “dog and pony shows.” While the United States saw clear benefits in allowing access, Foster shows how the ADF stuck to its old tactics of keeping the media at arm’s length, denying them freedom of movement, impeding their access to troops in the field, vetting their reports and shadowing their every move.

The contrast with what our Dutch and Canadian allies offered their journalists – and, by extension, the public – was stark. When it came to the media, Foster says, it was hard to believe we were all on the same side. From the start of their commitment in Uruzgan, the Dutch had a largely transparent system of media embedding, in which journalists were given access to troops on operations. For political reasons, the Dutch were determined to ensure the public was presented with “a realistic picture of what the mission entailed and the hazards it brought.” Reporters were given access to all aspects of army operations – including Special Forces, an access unthinkable in the Australian context. Equally unthinkable was the freedom given to Dutch reporters to “disembed” – to leave the base and report from civilian areas, and then re-embed.

For a time, the Canadians, operating in Kandahar, were even more open than the Dutch. Their reporters, too, could disembed and, unlike the Dutch and Australians, weren’t vetted by military officers for possible breaches of operational security. Shocked by the Canadian openness, the ADF was reported to have complained that Canada’s policy was “too liberal,” and four Canadian reporters lost their embedded places as a result.

Facing pressure from the media, a few politicians and even some within army ranks who felt the work of the troops was being ignored, the ADF tentatively opened up. Australian troops had been in Afghanistan on and off for a decade before an embedding program was introduced in 2010–11. More reporters were embedded in twelve months than the entire number over the previous ten years. Journalists usually were embedded for twenty-one days – although their actual time in Afghanistan might be only two weeks once travel and transit times were accounted for. There was no transparency in the selection process. Special forces were totally off limits. Under the rules – drafted without consultation with the media – reporters were to be escorted at all times and were to adhere to the directions of their escort. Stories and pictures were to be vetted before transmission – a rule that was not always enforced and was in any case unenforceable once reporters returned to Australia. There was no provision for disembedding – if you left the base, you couldn’t return and had to make your own way back to Australia.

At its height, the embedding scheme meant there were always one or two media crews in country. Generous by ADF standards, this was a miniscule presence compared to that of the Canadians who, with twice as many troops in Afghanistan as Australia had, offered their media forty times as many embedding opportunities.

Adopted reluctantly, the embedding program had clear benefits for the army, according to one of the scheme’s advocates, Lieutenant Colonel Jason Logue. In a review of the scheme published last year, Logue found that the media coverage that resulted was, overall, favourable towards the army. It was aligned with the messages the army was keen to promote – that the ADF looked after the troops, whose behaviour was beyond reproach and who were “making progress towards strategic goals.” While embedding was sought by journalists who argued it was in the public interest, it obviously doesn’t always lead to critical journalism that informs the public. Most embedded reporters, according to Foster, flew out of Afghanistan after fleeting visits that left them and their readers, listeners or viewers little wiser about the conflict.

But if officers like Logue see benefits from greater openness, they face entrenched resistance. While media restrictions were often justified on security grounds, the evidence suggests the resistance was overwhelmingly based on the army’s obsession with maintaining its image and reputation, its “brand.” Logue, for instance, quotes Lieutenant Colonel Darren Huxley, a former commander of the Uruzgan taskforce, who, despite the evidence, clings to the suspicion that embedded reporters are interested only in the army’s failings and “their own profile and professional gain.” Lieutenant colonels presumably are immune from thoughts of career advancement when they take to the field.

Don’t Mention the War sheds a revealing light on how one of our most important institutions resists independent scrutiny and open communication about what it does in the public’s name. The resistance recorded and analysed by Foster suggests to me that, despite overwhelming public esteem for the armed forces – esteem enhanced by journalists who surrender their professional detachment once embedded – when it comes to the media our army remains insecure, strangely lacking in self-confidence and more than a bit timid.

Foster attributes this to the army’s culture. I suspect it goes wider than that. Perhaps the army’s aversion to open communication and media freedom might simply reflect a broader national trait, deeply enthrenched in our political, government and bureaucratic culture. That culture is expressed in a closed, defensive officiousness, where all official information is assumed to be confidential except when someone in authority deigns to release it. In that sort of political environment, openness, engaging with the media and practices like embedding are impositions to be endured with gritted teeth and pinched nostrils.

Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, cited in Foster’s book, offers reluctant support for embedding as an unpleasant obligation that the army has to endure because it helps maintain public support for the army’s wartime mission. Presumably Campbell, now the military leader of Operation Sovereign Borders, sees no military need for the media to know firsthand what our navy does when it turns around asylum seekers in an operation shrouded in extraordinary secrecy, even by Australian standards. Democratic principles – like the public’s right to know what’s being done in its name – don’t get a look-in. •