I FIRST read Frantz Fanon while working as an English teaching assistant in Martinique, a small French island in the Caribbean. For most people this part of the world means rum and beaches, and Martinique certainly has plenty of both. It also produces writers and thinkers in remarkable quantity. Raphaël Confiant, one of its leading contemporary novelists, has claimed that only Israel has more graduates and intellectuals per square kilometre. Several local writers have had their works awarded the most prestigious French literary accolades. And then there is Frantz Fanon.

I’d arrived in Martinique duly prepared for my teaching duties, a not insignificant fraction of my luggage allowance allotted to a heavy book of Russell Drysdale photographs that the artist had taken during an outback trip. It was not a successful teaching aide. Martinique is a stunning part of the world, and my students were not very interested, on the whole, in photos of desert landscapes so different from the natural beauty of their own island. The book – rather like my lessons, I suspect – would teach me more about Martinique than it would my students about Australia.

One of them, an effusive girl who never missed an opportunity to get up on her feet in the middle of class and dance, was a journalist for the school newspaper. At some point she decided that the English assistant would make an interesting subject for an article. Things got off to a slow start, however. My interviewer hadn’t thought to prepare any questions, and when she finally settled on asking me what Australia was like, my attempts at description made her eyes glaze over.

It was at this point that I pulled out the Drysdale book, happy to put those precious grams to use. We were flipping through its pages, more slowly than we had done in class, when we came across a photograph of nine small Aboriginal children posing in one of the jeeps Drysdale and his friends had taken outback. My interviewer erupted. “Oh yuk!” she cried out, reeling back from the desk. “Look how ugly they are! They’re so... black!”

I was too stunned to react. Not because she found those beautiful little children so ugly – although this was in itself shocking – but because this student, like most people on Martinique, was black. An undeniably pretty young woman, her complexion was nonetheless at least as dark, if not darker, than those of the children in the photograph.

When I related this story to one of my teaching colleagues, she shrugged. “You need to read Fanon,” was her only advice. I bought a copy of Black Skin, White Masks at the local bookshop, and inside that slender little book I found a text whose virtuosity of style was apparent to me despite my patchy French. I was reading Fanon through the linguistic equivalent of a welding mask, and even then he was too bright to stare at directly.

Black Skin was his first book, a chapter of which was published in the prestigious journal Esprit when he was just twenty-five years old. It remains one of the most remarkable texts about racism. It was my first encounter with Fanon, and he has remained with me ever since. Not because I found the “answer” to why my student had convulsed at the sight of all that black skin – Fanon had theories, of course, and his book draws heavily on the apparatus of psychiatry, as well as the existential philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre – but for something that it would be a mistake to say was much simpler: Fanon could write, and he was not afraid to describe what he saw happening around him.

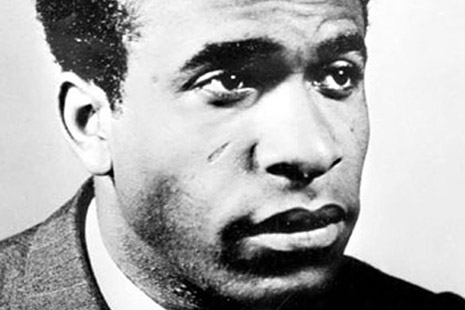

FANON died less than ten years after Black Skin, White Masks was published, succumbing to leukaemia at just thirty-six years of age on 6 December 1961. His short life was, however, of a breadth that’s difficult to grasp. At seventeen he left Martinique to fight with the Free French Forces against the German army, becoming a decorated soldier. After the war he studied medicine in Lyon, specialising in psychiatry.

In 1953 he took up a position at a psychiatric hospital in Blida, a city about forty kilometres southwest of Algiers. It was a fateful move. Algeria was still a part of France. Late the following year, on 1 November, the night was punctuated by the first strikes of what became the Algerian war. Fanon would side with the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale, or FLN, in the struggle to put an end to more than 120 years of French colonial presence. Expelled from Algeria in January 1957, he joined the political leadership of the FLN in Tunis and, while continuing his work in psychiatric hospitals, wrote articles for its newspaper, El Moudjahid. He also wrote two books.

The last of these, later translated into English as The Wretched of the Earth, had only just come off the press when he died. It was written in a double race against time. The Algerian war was grinding on in its seventh year, and negotiations over the Evian Accords, which would bring the conflict to an end, were yet to begin. Fanon was also seriously ill. He had always demanded a great deal of his body, and made no allowances for his declining health. As a psychiatrist he had run trials of sleep therapy for trauma victims of the war, but he himself only ever slept a few hours a night. The effort of producing one final book no doubt contributed to his rapid decline.

The Wretched of the Earth was widely condemned in France, even by many of those sympathetic to the Algerian cause, as an apology for violence. Fanon not only claimed that violence could serve as an organising force in the struggle for decolonisation; he also argued that it could act as a unifying force, a forge of national identity. In this context he considered that violence could be a beneficial praxis, an act that could “detoxify” an individual steeped in the rigid psychological structures of colonial society. Fanon described the process of decolonisation as “total, complete, absolute substitution,” and it was possible to interpret him to mean that, by killing a colonial oppressor, a downtrodden colonial subject could rise up as a “new Man.” It was certainly in this way that many, disciples and detractors alike, would read him.

Once the Algerian war came to an end Fanon was soon forgotten in France, and his intellectual legacy there has been modest. He was also erased from political discourse in Algeria, where his vision of a secular postcolonial world sat uncomfortably with the ideology espoused by the FLN as it tightened its control over the new Algerian state. Less than two years after his death, the Algerian parliament passed nationality laws under which Fanon would not have automatically qualified for citizenship.

While Fanon was neglected in his homelands, his works found an avid readership in the United States. He was particularly influential among intellectuals of the Black Rights movement. The 1968 edition of The Wretched, which its blurb described as “a veritable handbook of revolutionary practice and social organisation,” sold a million copies during the turbulent period of the Vietnam war. Since then, Fanon scholarship has remained active in American universities. In more recent years, however, even the most dedicated of Fanon scholars have felt the need to address the question: Is Fanon still relevant?

OF FANON’s three books, his first Algerian war book, A Dying Colonialism, has been neglected despite containing what, in my view, is some of the best writing Fanon ever produced. Published five years after the outbreak of conflict, the book was a plea to an apathetic French left to oppose the war and thereby help to bring it to an end.

Fanon sought to convince his readers of the futility of the war by demonstrating that what had taken place in Algeria was an irreversible social transformation. If the creation of an Algerian nation, independent of the French Republic, was no longer a matter of if, but when, then it made no sense to continue the war. Fanon developed his argument through a series of sociological analyses, presented as something like exhibits in a court case. One of the most fascinating of these studies concerns the radio. In the light of all the hype around the role of social networks in the Arab Spring, what Fanon was writing about communications technology in revolutionary Algeria more than fifty years ago makes for fascinating reading.

At the outbreak of the Algerian war in 1954, few non-European Algerians owned a radio. It was not simply a question of being able to afford one; according to Fanon, many non-European Algerians who could have owned a radio set did not. The only programs available were for the most part produced in Paris, and their burlesque content and erotic allusions could provoke “intolerable tensions” within an Algerian family. Fanon argued that the radio was seen as the voice of the colonial world, and as such carried an “extremely significant negative valency.” As local humour would have it, the radio was “the French speaking to the French.”

Attitudes to the radio changed dramatically when the FLN distributed leaflets announcing the creation of its own broadcaster. Voice of Free Algeria responded to the practical communications needs of the FLN leadership. It also responded, as Fanon put it, to the desire of the Algerian “to enter into the vast network of information… to introduce himself into a world where things happen, where the event exists, where forces act.” Newspapers, such as the one Fanon wrote for, could only have a limited impact among an illiterate population, and their distribution was difficult and often dangerous. The radio suffered from none of these drawbacks, and as cheap, battery-operated transistor radios became available throughout the 1950s, even the most remote villages, far from the electricity grid, could tune into the revolutionary broadcasts.

So began a war of waves. French technicians, their skills sharpened during the second world war, set about jamming the broadcasts. Fanon evokes the scene of a family huddled around a radio, straining to hear a signal so faint that often only the person closest to the speaker could make out what was being said. Where the details of a particular news item could not be detected through the fog of white noise, Fanon, in an astonishingly postmodern fresco, claimed that the family would simply invent their own story, thereby becoming authors and actors in the history of the revolution. What mattered was not so much the content, but the opportunity to participate in the construction of a narrative. For Fanon, it was a critical step towards the creation of a nation in the minds of the Algerian people.

Fifty years on and an information revolution later, what has changed? One of the most valuable insights into the role of communications technology in the Arab Spring is contained in an account of the Tunisian Revolution by Lina Ben Mhenni, who has emerged as one of its most prominent activists and bloggers. Despite all the hype about the unprecedented revolutionary potential of social media, there are striking parallels between the roles that Fanon and Ben Mhenni ascribe to the respective communications technologies of their time.

As Fanon did for the radio, Ben Mhenni cites statistics showing an exponential growth in the number of Tunisians signed up on Facebook, rising from less than 10 to almost 25 per cent of the population in a little more than a year. The implications for internet usage are clear. “Today,” she writes, “of a population of eleven million, almost all those of demonstration and voting age have direct access to the internet or a link to cyberspace.”

Activists like herself also had to contend with the internet equivalent of signal jamming. In Tunisia, the Ben Ali regime reacted to the increase in internet activism by censoring blogs critical of government policy; email and social network accounts were also hacked. As Ben Mhenni writes, far from being put off by these setbacks, internet censorship only confirmed her conviction that something needed to change. It was her own experience with internet censorship that provoked her to become an outspoken critic of the regime. From that point on, she began to construct her own narrative of her struggle against oppression.

Fanon and Ben Mhenni are in full agreement over the relationship between communications technology and social transformation. Fanon never suggested that the radio was somehow responsible for creating the revolution in Algeria. The Transistor-Radio Revolution sounds preposterous, yet the Arab Spring has become known as the Facebook Revolution.

For Fanon, like Ben Mhenni, communications technologies can allow people to share ideas and see beyond the rigid barriers of the oppressive society in place around them. Changes in the usage of the radio or the internet can be a sign that social transformation is under way. These technologies can act as a catalyst, and an essential one, but they are not the transformation itself. As Ben Mhenni has stated, social media may have brought people out onto the streets, but it was the courage of those people who remained in the streets, despite the threat of police retaliation, that toppled dictators.

The radio and the internet are, of course, very different communications technologies. The radio was so convenient for the FLN because its audience was, on the whole, illiterate. The contrast with the situation in Tunisia today could not be starker. Mohamed Bouazizi, whose self-immolation set off the mass protests that became the Arab Spring, was, like so many young Tunisian women and men, a university graduate without a decent job. When I travelled to Tunis earlier this year, everybody I met, even the young man who took me on a culinary tour of fried Tunisian specialities in the food shop where I would buy my lunch, was bilingual. Ben Mhenni herself blogs in three languages. Blogs can host media in any format, but they are above all a textual medium.

Perhaps the most significant difference lies in the individual nature of internet interactions. Fanon saw the radio as a hearth of the revolution that would draw a family together to hear the latest news. Ben Mhenni, on the other hand, describes a disparate network of activists, each tapping away at the keyboard of their own laptop – even when seated at the same table. Fanon suggested that the radio could become a powerful pedagogical resource in the construction phase of the Algerian nation. Ben Mhenni sees the internet not as a pedagogical tool, but as a forum for participatory democracy. At the very least, it is a space where individuals can record their personal narratives of their struggles to make the world a better place, and meet other, like-minded people.

Fanon concluded his book by suggesting that the radio had opened up “unlimited horizons” for those fighting for a free Algeria. The tragic reality is that in the aftermath of the war, the FLN installed itself as a single party and enforced a single narrative of Algerian history. Fifty years later, as the first anniversary of the Arab Spring approaches, the gains of that equally singular social movement also appear to be under threat. Might not this be the strongest argument for reading Fanon again? Like those involved in the upheavals across the Arab World, Fanon did not know what the future would bring. His books do, however, provide an insight into the enormous challenges which Algeria faced as it sought its independence from France, challenges which are no less daunting than those that the Arab Spring countries must also address. His books describe the extraordinary potential of revolutionary situations; his example serves as a reminder that an oasis in the distance may be a mirage. The communications technology may have evolved, but this is no guarantee that history will not repeat itself. •