Cyril Frank Elwell: Pioneer of American and European Wireless Communications, Talking Pictures and Founder of C.F. Elwell, Limited (1921–1925)

By Ian L. Sanders and Graeme Bartram | Second edition, revised and expanded | Castle Ridge Press | US$43.50 | 189 pages

Cyril Elwell has not left many traces. Stanford University’s archives hold multiple drafts of an autobiography no one would publish. The Palo Alto Times carried a one-column obituary when he died in 1963. His name is on a plaque outside a house in Silicon Valley where, according to the inscription, other people did something that “led to modern radio communication, television and the electronics age.”

It’s true that Elwell gets much of a long chapter in Hugh Aitken’s fine history of early twentieth-century American wireless because of his role in a “revolution in the art of radio.” But it has taken Ian Sanders and Graeme Bartram to do what Elwell himself couldn’t manage through all those autobiographical fragments in the Stanford archives — piece together and publish a comprehensive account of the work and life of this important Australian link to the early days of Silicon Valley.

About a decade after Leland Stanford Junior University opened its doors in the 1890s, the Australian-born Elwell began a BA in electrical engineering. Stanford, as Sanders and Bartram write, was set up to teach “the traditional liberal arts and the technology and engineering that were… changing America.” Its four-year electrical engineering course and related work program quickly acquired a reputation that reached young Elwell in Sydney via an American working at the Ultimo Powerhouse. On a lecture tour of Australia the year Elwell graduated, Stanford’s founding president, David Starr Jordan, mentioned this “most brilliant Australian student” to the Brisbane Telegraph.

“It cannot have been unusual in Australia in 1902 for a young man with a technical bent to want to study electrical engineering,” writes Aitken. “What was distinctive about Elwell was his bullheaded determination that, with no financial support from his family, with the slimmest of cash resources of his own, and with no assurance whatever that his previous education would gain him admission, he was going to study electrical engineering in America, and not just any university, but at Stanford in particular. And it must have been this determination, this confidence that the thing could and would be done, that gave him the aid and encouragement of people on whom he had no claim except friendship.”

Elwell was born in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond in 1884. There is no official record of the death of his birth father, an American from Rochester, New York. Cyril took the surname of his mother Clothilda’s second husband, an English journalist who became the Sydney Morning Herald’s principal state political reporter. After Thomas Elwell died of kidney disease on Cyril’s eleventh birthday, Clothilda married the owner of Sydney’s Grosvenor Hotel. Aitken suggests that Elwell “became accustomed to abrupt change, and perhaps learned not to commit himself too completely to any given state of affairs.”

Living at the hotel with his family, he learned about electricity from a German engineer who maintained the electrical systems: at the time, being “lighted throughout with Electric Light and Gas” was luxury. In 1900, after finishing school at nearby Fort Street High, he travelled in Europe with his family for six months. They visited the Universal Exhibition in Paris, where one of the hit attractions was Valdemar Poulsen’s “telegraphone,” a recently patented magnetic wire recorder the Danish inventor had used to record the voice of the Austrian emperor.

Back in Australia, Elwell did a course in physics at Sydney Tech then started an apprenticeship with the Electrical Section of the NSW Railways, where he worked upgrading the Ultimo Powerhouse to supply electricity to Sydney’s trams. Deciding he wanted to study electrical engineering at the university he had heard about from the visiting American, Elwell worked his passage to San Francisco then studied further to pass the entrance exam.

He remained a “big current” man through his studies at Stanford, undertaking a final-year project on the design of high-current transformers for electrical smelting furnaces and then landing a job with a Californian steel company. He was not especially interested in the “small currents” of telephone and telegraph engineering when one of his Stanford professors recommended him to the Oakland bankers backing a local wireless telephone start-up.

Elwell responded as he would many more times in his career: he took a big risk, made something remarkable happen, got an even better idea, fell out with people he really needed to get on with, and moved on to something else.

Early “spark” wireless transmitters generated intermittent electrical emissions that worked well enough for the dots and dashes of telegraph signalling. Elwell was one of the pioneers of a new method, “continuous waves.” Working for the start-up in San Francisco, he made enough progress with spark apparatus to persuade the Oakland Tribune that the wireless telephone was “assured of success.” But he convinced himself of the opposite: that intelligible sounds could not be transmitted over long distances without continuous electromagnetic waves.

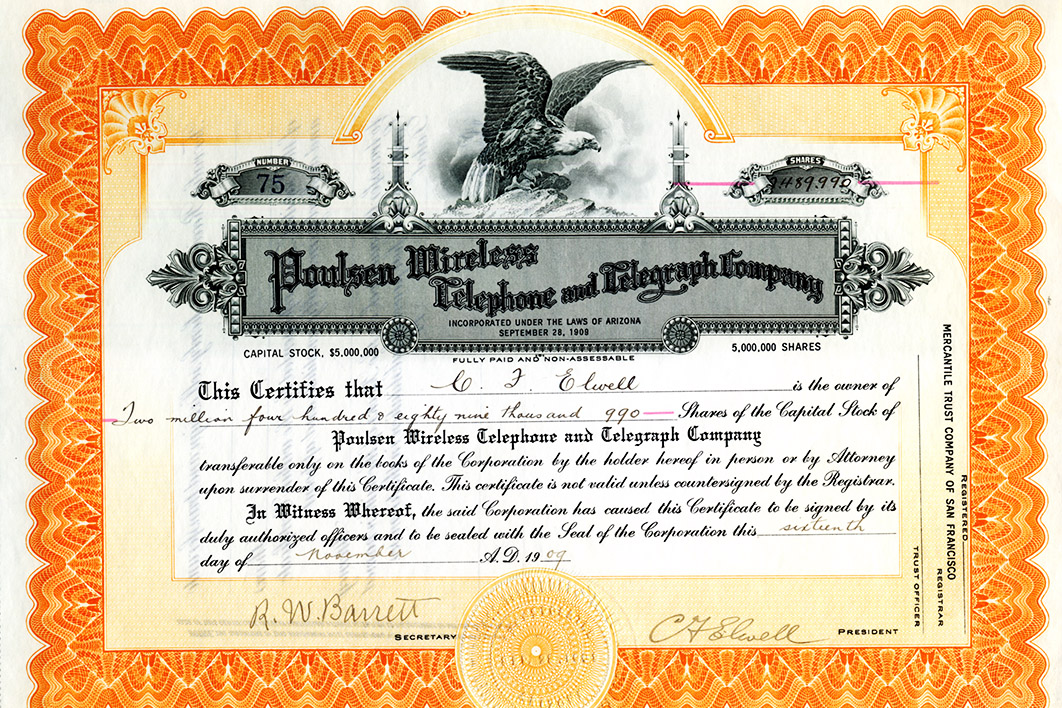

Different inventors developed three ways to generate these waves. One, patented by the Dane Valdemar Poulsen, was the “arc.” Poulsen used this technology to communicate by telephone across a distance of 270 kilometres in 1907. Elwell bought US rights to the “Poulsen arc,” demonstrated the equipment in San Francisco, and set up a company with himself as president and chief engineer and David Starr Jordan, the Stanford president, as a founding investor. Stations opened in Stockton and Sacramento in 1910. A third, at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach, became a giant landmark for local shipping. Elwell developed the equipment, including a better receiver. Other stations followed in cities like Seattle and Portland on the west coast, Kansas City and Chicago in the east, and, in 1912, Honolulu.

Despite its impressive technical achievements, the company struggled to make money. It was recapitalised and renamed, twice. In the process, Elwell lost control of it. From 1911, the person with that revered Silicon Valley moniker, the founder, was an ordinary director and only a small shareholder in what was now the Federal Telegraph Company.

Technological translator: Cyril Elwell (fifth from the left) at a Federal Telegraph Company reunion in Palo Alto in 1956. Lee de Forest is third from the left. History San José

Wireless telephony was the goal, but continuous waves also had important benefits for wireless telegraphy. They could be tuned to particular frequencies and they didn’t dissipate electrical power to the same extent as spark transmissions. When Elwell travelled to Washington in 1912 to try to sell Federal Telegraph’s technology, the US navy already had equipment that could feed into an antenna twice the power that Elwell’s could. But when a test was set up to communicate across America with San Francisco, observers were stunned to find Federal Telegraph’s Honolulu station listening in as well. This “unheard of” distance provided big possibilities for US military command.

Federal got a contract for a station in the Panama Canal Zone in 1913. It went into service two years later. Others followed in the Philippines, Pearl Harbor, San Diego, Puerto Rico, Guam, Samoa, New York, Annapolis and Lafayette, France. By the end of the first world war, the US navy’s oceanic communication system was the world’s best and Washington, DC could communicate with ships anywhere in the Caribbean, the Pacific and the Atlantic.

By then, though, Cyril Elwell was long gone from the company that supplied all the transmitters. Sanders and Bartram say he disagreed with the level of expenditure needed to extend the company’s network to Japan and China. Other directors were given an ultimatum: they could have the engineer and founder, or they could have the financier who now controlled the company. They picked the financier. One of Elwell’s own hires, Leonard Fuller, took over the engineering and went on to design what Aitken calls “the third and greatest generation of arc transmitters.”

Based in London from May 1913 and Paris from 1916 to 1920, Elwell worked as “a kind of freelance engineer” for anyone who paid, among them the Royal Navy (which used the Poulsen arc system on all its vessels by the end of the war), the British Post Office, the governments of France and Italy, and the company holding the Poulsen patents for the British Empire. A major coup was the selection of Elwell–Poulsen’s system ahead of Marconi’s and other competitors’ for two large stations near Oxford and Cairo in the early 1920s, the first steps in Britain’s long-delayed Imperial Wireless Chain. Marconi’s new shortwave “beam” system dominated later British stations, and valves overtook arcs as the technology of choice for generating continuous waves.

Building a big, Californian-style home in Surrey in the 1920s, Elwell became something of a “local celebrity,” write Sanders and Bartram. He was an early investor in the Mullard Radio Valve Company (eventually bought by Philips) and claimed to have made a lot of money from it, though Sanders and Bartram say “the scope of [his] involvement following its formation in 1920 is unclear.” He established a company, C.F. Elwell Limited, hoping to profit from the boom in radio broadcasting in the 1920s, but the enterprise was not a success, and he “all but erased the episode from his later recollections of history.” The second part of this handsome, expanded edition is filled with pictures and descriptions of the “Aristophone,” “Statophone” and other receivers that C.F. Elwell Limited manufactured in Britain.

Elwell also set up a company to manufacture and market “talking pictures” equipment, licensing American Lee de Forest’s Phonofilms system for Britain and its overseas territories in 1923. The company was liquidated in 1929 as better technologies developed by bigger corporations came to dominate the retooling of cinemas for “talkies.”

De Forest and Elwell had history. Elwell gave de Forest a job in 1911 at Federal Telegraph. There, in the laboratory and factory on the corner of Emerson Street and Channing Avenue in Palo Alto, as the commemorative plaque now reads, “with two assistants, Lee de Forest, inventor of the three-element radio vacuum tube, devised in 1911–13 the first vacuum tube [valve] amplifier and oscillator.” Amplification of tiny signals was a crucial advance that made long-distance telephony, broadcasting, talking pictures and much else possible, hence the further tribute that “worldwide developments based on research conducted here led to modern radio communication, television and the electronics age.” Elwell’s role was to have founded the company where de Forest and his assistants did this work. He was never happy with the credit de Forest got, especially his later self-styling as the “father of radio.”

Elwell married twice. Two of the four children he had with his first wife, Ethel, died very young, one at six weeks, the other just before his fourth birthday. Ethel died in 1927, aged thirty-seven. Two years later, Elwell married Helen Hubbard, the resident piano player at British Talking Pictures, where he was working as an adviser. They had a daughter in 1932.

By the 1930s, Sanders and Bartram say, Elwell’s technical skills had “lost their edge.” He was commissioned to design and construct transmitters for the BBC, and some stations for the early-warning radar system constructed along the English coast before and during the war. In 1940, he took his family to live in the United States. From 1947, he consulted to the young Hewlett-Packard, another Silicon Valley start-up founded by Stanford graduates, where he was remembered as “extravagantly garrulous,” a ready source of “tales of de Forest’s perfidy.”

For contemporary entrepreneurs dreaming of founding disruptive enterprises, “Cy” Elwell’s story is cautionary. These biographers conclude he was “visionary” — about continuous wireless waves, talking pictures and television — but “not a particularly deep-thinking theorist.” He was a “highly competent, practical implementer of engineering concepts” with “little tolerance for those who questioned his technical judgement.” Efficient, cold even, in dealing with engineering challenges, he could be emotional in personal interactions and boardrooms.

Success in what came to be called Silicon Valley always needed more than big ideas, certainty and self-confidence. Elwell was “torn between the need to act alone — where he had the best chance to receive credit for what he saw as his exceptional technical foresight — and the need for funding which could only come from large, established enterprises.”

Hugh Aitken calls Elwell a “technological translator,” someone who “worked at the interface between the laboratory and the marketplace.” With continuous waves, he “engineered a shift from the world of purely technical criteria… to a world where market considerations played a major role,” but paid heavily for it. “As control shifted from the individual innovator to the corporate institution, as technical development became increasingly a function of market performance, stresses appeared that in the end made joint action impossible.” •