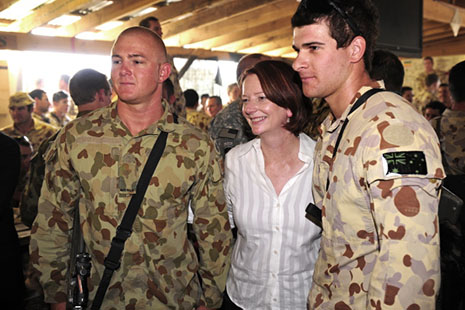

BARACK OBAMA wants American troops out of Afghanistan, starting next July. His commander in Afghanistan, General David Petraeus, wants to keep fighting indefinitely in what he acknowledges is an unwinnable war. Where should good friends of America stand? Julia Gillard refuses to follow the US president by nominating 1 July next year as the starting date for the withdrawal of Australian troops. But she stopped well short of promising General Petraeus to keep them there for decades when the two met briefly in Afghanistan during her eleven-hour visit on 2 October.

The issue has been complicated by the Coalition’s decision to go back on its support for Australia’s existing contribution of 1550 troops on the ground and another 800 as back-up in the region. It now wants to send more troops, backed by Australian fighter planes, tanks, heavy artillery and attack helicopters. Adding to the complexity is the decision by the director of military prosecutions, Brigadier Lyn McDade, to charge three members of a commando unit with serious offences, following a night raid in a village housing compound in which five children and an adult were killed.

The politically puzzling question is why Ms Gillard doesn’t do more to back President Obama’s initial withdrawal date. Apart from ruling out tanks as unsuited to the terrain, she says she will send more troops and weaponry if the Australian Defence Force requests it. Perhaps the senior echelons of the ADF will not ask for more – their ranks are not dominated by bellicose warriors hellbent on sending the lower ranks off to an unending war. But President Obama could certainly do with some support, as is made clear in Bob Woodward’s new book, Obama’s Wars, in which the veteran Washington Post journalist gives an unsympathetic account of the president’s efforts to extricate the nation from Afghanistan.

In a nationally televised address on 31 August, President Obama gave a powerful explanation to the American people for his decision to end the US combat mission in Iraq and start doing the same in Afghanistan. “We have spent over a trillion dollars at war, often financed by borrowing from overseas,” he said. “This, in turn, has short-changed investments in our own people, and contributed to record deficits… Too many families find themselves working harder for less, while our nation’s long-term competitiveness is put at risk.” Referring to his plan to begin withdrawing from Afghanistan next July, he said, “Make no mistake: this transition will begin, because open-ended war serves neither our interests nor the Afghan people’s.”

The reason for making this unequivocal declaration is understandable in the light of Woodward’s revelations about the stiff resistance President Obama faces from General Petraeus. After the president asked him for a range of options to exit Afghanistan, General Petraeus gave him only the single option of an open-ended increase of 40,000 in troops. Petraeus told Woodward, “You have to recognise also that I don’t think you win this war. I think you keep fighting… You have to stay after it. This is the kind of fight we’re in for the rest of our lives and probably our kids’ lives.”

Woodward shares this type of American “exceptionalism,” which utterly ignores the parlous state of the US economy. So did the Washington Post in its 29 September editorial on Woodward’s book, in which it complained, “Obama repeatedly cites the cost of the war and the need to shift resources to domestic priorities – though spending on Afghanistan is well below 1 per cent of US gross domestic product.”

If the war continues indefinitely it will create an enormous toll in maimed veterans and a dollar cost to the US government that will soon reach 1 per cent of GDP a year. (To put this figure in perspective: if Australia spent 1 per cent of GDP waging war in Afghanistan the cost would be $13 billion a year, quite a bit higher than the $1.2 billion we currently spend on the deployment.) The US Congressional Budget Office projects that the fiscal deficit will be well over 3 per cent of GDP after 2020 — a recipe for economic malaise. Yet, unlike Obama, many members of the American political class presume that the United States has no need to control its vast military spending, let alone acknowledge the recent folly of starting an economic war against China, the country that funds its deficits.

DURING her visit to Afghanistan, Ms Gillard said that the ADF’s mission is to train the Afghan National Army so it can make sure the country “does not again become a training ground and a place that sponsors violence and terrorism that is visited on innocent people around the world.” She said that the chief of the ADF, Angus Houston, has advised her that Australia’s specific responsibility to train the army’s 4th Brigade would probably be completed in two to four years. Ms Gillard said a phased withdrawal would then begin (in other words, possibly as late as 2014).

There is no way to guarantee that a country will never be used as a base by a small group determined to undertake a terrorist attack. Nevertheless, there seems a reasonable chance that the Taliban would stick to its longstanding policy of never engaging in international terrorism if it regained formal power in southern Afghanistan or throughout the country. Many analysts consider that, in order to retain its renewed governing role, the Taliban would not repeat the mistake it made when it was in power before 11 September 2001. Back then, it let al Qaeda set up infantry training camps for the Taliban’s own soldiers but also let it run separate courses for grooming foreigners as terrorists. That decision ignored the fact that al Qaeda ultimately has very different interests from the Taliban’s. (See James Fergusson, “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” Prospect, September 2010.)

A former terrorism analyst with the Australian Federal Police, Leah Farrall, estimates that al Qaeda only has about 200 members — the same as ten years ago. She argues that the organisation is keen for foreign troops to stay in Afghanistan because it helps its recruiting drive when westerners kill people in Islamic countries. In contrast, the Taliban wants to expel foreign military forces. Supporters of a protracted foreign presence often ignore this crucial distinction.

Many Australian politicians seem to regard the Taliban as synonymous with the Arab-led al Qaeda. Although there certainly are dedicated Islamists within the loose alliance of Afghan insurgents and resistance fighters, its ranks also include disaffected farmers, minor criminals and drug traffickers, as well as impoverished people who, as Ms Gillard accepts, are motivated to go on the Taliban payroll by the need to feed their families.

While Australian infantry train the 4th Brigade, a 300-strong special forces contingent conducts offensive operations to kill suspected members of the Taliban. In contrast to traditional infantry, the special forces engage in state sanctioned killing of particular individuals on lists compiled from intelligence information, sometimes from dubious sources. Consequently, innocent people are sometimes killed because the information is wrong. On other occasions, Australians have killed police, a district governor, children and other civilians in bungled operations. Apparently, no members of al Qaeda have been killed.

No one knows how many Australian-trained Afghan troops will end up fighting for the government, going over to the Taliban, or deserting. Journalists in Afghanistan have been told that equipment supplied to trainees by Australia has been used in improvised explosives fabricated by the Taliban. If the Taliban pay more, or look like winning, a significant proportion of the trainees could switch sides. In these circumstances, there is no reason why Australia should not begin withdrawing its troops well before the end of 2014.

Given that the special forces are not contributing to the mission of training the 4th Brigade, they should be withdrawn before Christmas, or July 2011 at the latest. President Hamid Karzai’s government could hardly complain. It’s almost nine years since the Taliban was deposed – more than enough time for the new leaders in Kabul to gain sufficient public and local military support to establish security. Apart from the fact that it is too corrupt and inept to win widespread respect, the government has no motive to provide for security when western troops remain to save its neck.

Against this backdrop, Ms Gillard went beyond the requirements of standard diplomatic palaver when she said after stopping in Kabul, “I also had the opportunity to meet with the president of Afghanistan, so that was very enjoyable.” She also told the ABC’s 7.30 Report on Tuesday that she did not raise the issue of corruption with Karzai.

FOR the last twelve months the special forces have supplemented their assassination programs with less aggressive operations intended to win hearts and minds. But their withdrawal would prevent a repetition of the appalling episode on 12 February last year when the five children were killed. Unfortunately, the ADF’s investigative service was not asked to examine what happened until mid 2009. It then set out potential grounds for charges in its report to Brigadier McDade in November. She asked for further investigations, and waited for an obligatory response from the ADF to her conclusions, before announcing on 27 September that she would lay charges including manslaughter, dangerous conduct, failing to comply with a lawful general order and prejudicial conduct.

The charges provoked a torrent of abuse against Brigadier McDade on various websites. Many comments were from people who clearly don’t know what happened but started from the premise that no one should ever be charged with anything they do in war. Those charged are entitled to the presumption of innocence, but the process followed so far accords with the rule of law. The ADF fully supports the requirement that its members obey the rules of war. An independent investigator examined the operation and an independent prosecutor laid charges under a new military justice system. The parliament had intended that a special division of the federal court hear any charges, but the High Court has thrown doubt over its validity. A court martial will now hear the charges in a heated atmosphere that will test the impartiality of its members.

After the raid, the Afghan government complained publicly that Australian troops had not followed a NATO directive that local soldiers must be included in this type of operation. The directive also requires foreign troops to retreat if there is a risk of civilian casualties — one reason being that botched operations bolster support for the Taliban.

Unhappily for the completeness of the case, it appears that the investigators were not allowed to travel to the village to inspect the house, nor to interview witnesses who still live there or have shifted to Kandahar. Some of them have told journalists that they feared the Taliban was attacking them. They say that the Australian forces wrongly believed that a senior member of the Taliban was present – a claim that defence sources unofficially confirmed after the ADF subsequently announced that the special forces killed this particular suspect several weeks later at a different site.

The evidence before the court martial is expected to explore whether planners undertook the normal level of surveillance before the raid, and whether there was a sudden change of plan on the night. Usually, surveillance would have detected the presence of a large number of women and children in the house, but there might be an explanation for why it seems to have failed on this occasion.

Perhaps it will not be possible to establish whether the Afghan man who allegedly fired on the troops from a room within the house was an insurgent or simply someone trying to protect his family (or both). Either way, those charged have said they were entitled to defend themselves. A key issue is likely to be whether one or more of the troops threw a hand grenade, or continued to fire, well after it became clear that children were in danger. The answers are now matter for the court martial. (One possible alternative would have been for Brigadier McDade to refer aspects of the case to the Commonwealth director of public prosecutions, but it is hard to argue she was not entitled to lay the charges.)

The court martial is not expected to conclude until well after the proposed debate on Afghanistan that the government has agreed to hold before parliament is due to rise on 25 November. Although it won’t happen, parliamentarians should be allowed a free vote, unshackled by party discipline, so they can canvass the full range of issues raised by our continuing participation. •