To describe the 2016 US presidential election campaign as an extraordinary one for both Republicans and Democrats is scarcely a news-making statement. Yet, as the days and weeks go by, it becomes clearer that the Democrats have a manageable problem on their hands while the Republicans are faced with something altogether more challenging. The fact that a “nuclear” option is seriously being discussed underlines how far the Grand Old Party has travelled in recent years.

The challenge facing the Democrats is to preserve Barack Obama’s legacy, especially his seminal healthcare reforms, to build on the economic recovery, and to look for opportunities to break the legislative logjam imposed by the Republican-controlled Congress. On the basis of her experience and expertise, Hillary Clinton always seemed the logical choice. In fact, no other candidate in recent history has seemed so preordained, not even George W. Bush in 2000, and not even Jeb Bush in 2016.

Under such circumstances few would have predicted the emergence of senator Bernie Sanders, an independent, self-described socialist, as a serious challenger for the Democrat nomination. In many ways Sanders’s ability to generate hope and enthusiasm among his supporters is reminiscent of Obama’s Yes We Can campaign in 2008, and in giving voice to the left he is also emulating George McGovern in 1972. His idealism is in direct contrast to Clinton’s pragmatism, but his supporters seem more interested in his ideas than in whether he can implement them.

Sanders’s appeal is such that he has been able to beat Clinton in states like Nebraska, Kansas and Colorado, but despite this greater-than-expected regional diversity, all these are states whose electorates are made up mostly of white voters. As his poor performance in Mississippi showed, he has not been able to garner the support of African Americans and Hispanics. This will become an increasing problem as the primaries move to more diverse states, like Florida and California, with large numbers of delegates. Of course, Sanders is emboldened by his surprise win in Michigan, but Clinton has such clear leads among delegates (760 to 546) and super delegates (461 to 25) that it is very hard to see how Sanders can make up the difference.

While some observers are asking if the Sanders revolution has hit a wall, and while it is almost certain Clinton will go to the convention with a majority of delegates, Sanders doesn’t appear to be about to fall by the wayside – as Al Gore did in 1988 and Paul Tsongas did in 1992, in both cases having carried seven states early and then faltered. If Sanders’s February fundraising totals are an indicator (he raised US$42 million in one month), the political revolution he is calling for still has staying power.

By remaining in the race Sanders can push Clinton on her policies and, with sufficient delegates, he can also influence what happens at the nominating convention. Beyond this, he may have ambitions to build a reform movement; doing this through a third political party is very difficult, though, as Ross Perot discovered with his Reform Party. The key question is what will happen to Sanders’s youthful and enthusiastic followers – can Clinton capture them, or will Sanders, in supporting Clinton’s nomination, deliver them to her?

These are interesting times, then, for the Democrats, but an orderly process is unfolding. The Republicans, on the other hand, are in a state of unprecedented chaos.

This isn’t the first presidential race in which candidates have been poorly qualified; names like Ralph Nader, Ross Perot, Rick Santorum and even Ronald Reagan come to mind. It isn’t the first race in which bigotry and racism have raised their ugly heads; think George Wallace’s “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” speech in 1963. And it’s certainly not a first time for bitter, personal fights and nasty insinuations.

Donald Trump has engaged a significant (but not necessarily winning) segment of the population by capitalising on their anger, fears and sense of doing less well than less-deserving others. This is broadly what all candidates do, and they also need a strong streak of bravado and a substantial ego, which Trump has in spades.

What is different about the campaign Donald Trump is waging is its crudeness, its violent language and its utter disregard for the facts. When challenged, Trump’s default defence is simply to shrug off questions and attacks – like the recent one by Mitt Romney – or to engage in personal diatribes on social media. Until very recently the mainstream media has been complicit in this, failing to follow up on serious issues such as his tax returns and gleefully reporting every nasty remark or tweet. Worse, Trump has played these games so well that he has forced his opponents to joust on the same decidedly unpresidential playing field.

As a consequence, the Republican debates have degenerated into nothing more than dirty, demeaning schoolboy jibes. Trump’s campaign statements (it’s hard to call them policies) are based on the flimsiest of foundations, with little or no regard for accuracy, reality, or the constraints imposed by the constitution and the other, equally powerful branches of government a president must work with. His rallies seem to revel in violent threats to outsiders – whether they are illegal immigrants, Muslims or simply those who dare to disagree. As Roger Cohen of the New York Times has written, “Violence is woven into Trump’s language as indelibly as the snarl is woven into his features.”

Trump has captured his audiences and his voters not by reflecting his political capacities but by highlighting his fame and money. In return he is seen as a true outsider beholden to no one, and as a brilliant businessman, which in reality may not be true.

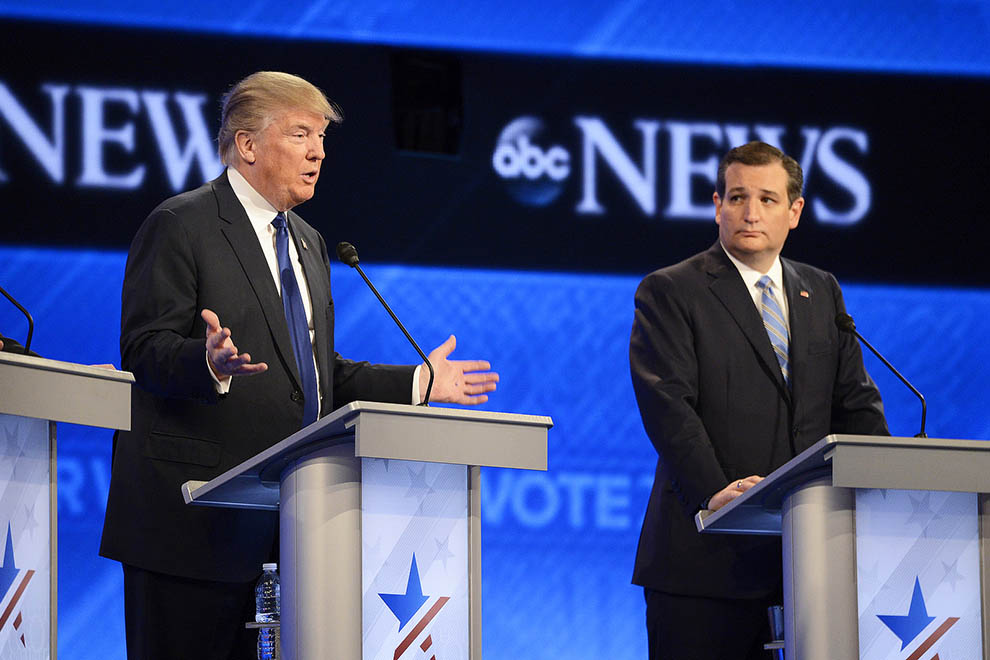

The situation is rendered more disastrous for the Republican Party because the only candidate who seems to have any chance of beating Trump – senator Ted Cruz – is seen by the establishment as just as scary as Trump. Cruz’s xenophobic and racist rhetoric echoes Trump’s but is just delivered in a less colourful way.

Currently Trump has 458 delegates, well ahead of Cruz, on 359. But he needs 1237 to win the nomination, and as long as Cruz continues to do as well as he has to date, and as long as Marco Rubio and John Kasich stay in the race, it’s hard to see how Trump can get there with a clear lead. That’s why Republicans concerned about the future of the party are hoping against hope that Rubio and Kasich win in their home states, Florida and Ohio respectively, on 15 March. Delegates in these states are awarded on a winner-take-all basis, so wins by these two candidates would deprive Trump of 165 delegates.

Ultimately, candidates like Trump and Cruz (and others like Sarah Palin) are creations of the very Republican Party that is now terrified of their power and influence. All the Republican candidates are capitalising on the anti-intellectualism that is increasingly prominent in American politics, especially on the right. Many Americans are ill-informed on issues like geography, history, climate change, Obamacare and even their own political system, and racial animosities and bigotry surface readily when times are tough and the environment encourages their expression.

Ben Fountain has argued in the Guardian that the Republican Party’s dog-whistle appeal to racism started after the Johnson administration enacted the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Many southern Republicans, led by Barry Goldwater, were enraged, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan refined that anger, and the party ended up with what conservative commentator Robert Kagan calls “racial derangement syndrome.” Since 2008 this has played out in Republican claims that Obama is anti-American, un-American or non-American, and that his policies are not only wrong but also subversive.

Finally, the Republicans’ obdurate obstructionism in Congress, their failure to come up with meaningful legislation, and most recently their refusal even to consider the president’s nominee for the vacant Supreme Court position have all taught party supporters that political institutions and traditions are there to be ignored or overthrown.

And so the GOP establishment faces what some call its nightmare scenario: Trump versus Cruz. The party’s efforts to disown or undermine Trump have been too half-hearted, too little, too late. Now, with no obvious, appealing alternative, they face the prospect of a race between two candidates who between them alienate a sizeable proportion of voters. (Interestingly, a battle between these two candidates may also alienate their mutual supporters.)

It has to be said that the GOP deserves to be in this dreadful quandary. After Mitt Romney’s defeat in 2012, a report commissioned by the party leadership found that its dismissal of minority concerns, intolerance towards gays, celebration of wealth, and fetishism of Ronald Reagan spelt doom for its electoral prospects. The report warned that although the gubernatorial wing of the party is flourishing, the federal wing is increasingly marginalised and out of touch; unless changes were made, it said, Republicans would find it extremely difficult to win a presidential election in the near future. Those recommendations have languished unaddressed.

Changes to the Republican primary process since 2012 have only made things worse. The GOP wanted to make sure its likely nominee emerged early enough to give him or her a strong chance in the general election, so they frontloaded Super Tuesday 2016 with primaries in a majority of southern states. That made life easy for Trump and Cruz and more difficult for Rubio and Kasich. Much now hangs on the results of Republican primaries on 15 March in Illinois, Missouri and North Carolina, as well as in Florida and Ohio, and on 22 March in Arizona and Utah. By 1 April, if this were a typical election campaign, the final candidate for the general election would be known.

But nothing is certain about the next few weeks. The options seem to be just three: Trump as the nominee, a brokered convention, or what has been referred to as the “nuclear option.” What would a brokered convention look like? Few precedents exist, and it is quite possible that a party unable to coordinate a plan to stop Trump despite the existential threat he poses might not be able to organise a coherent brokered convention. The nuclear option must start now: it would involve a clear declaration from authoritative voices that Trump is unacceptable as president, combined with a campaign to attack his character and temperament so hard-hitting that it would shock his ardent supporters into withdrawing their support.

Both these options would require some agreement about who the alternative candidate would be. It would also require much more bravery in the face of Trump’s demagoguery than has been seen to date. From time to time Trump has indicated that, if challenged, he would run as an independent candidate. The GOP should look to what happened in 1912, when former president Teddy Roosevelt, who had unsuccessfully sought the Republican Party’s nomination through the first-ever primaries (he won most of them, but not a majority of delegates), ran on his own ticket against William Howard Taft. Although Roosevelt’s was one of the most successful third-party candidacies in history, he split the Republican vote and a Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, won the presidency with 42 per cent of the popular vote.

The Republican leadership planned a dynastic restoration with Jeb Bush in 2016. Instead they triggered a revolt of their voters, enabled Trump – no conservative, and barely a Republican – to emerge as their leader, and potentially signalled the end of the party of Lincoln. •