Updated 16 February 2016

The Labor Party might have the edge as Western Australians prepare to vote in the general election on 11 March, but it would be wrong to believe the result is cut and dried. Too many variables are in play for the result to be predicted with any confidence.

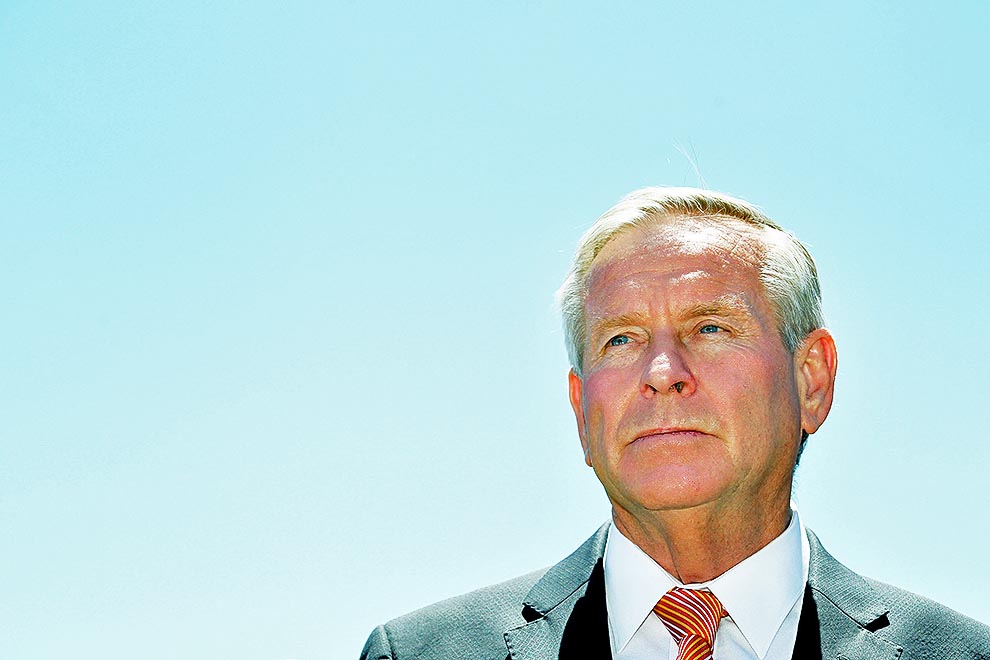

One variable is the unpredictability of campaigning. A word out of place or unexpected economic news – good or bad – could well have a significant impact on the political pendulum. But two other factors are combining to make it tough for Liberal Colin Barnett to become the first WA premier to achieve a third consecutive victory since four-year terms were introduced in 1989.

The first is the “It’s time” factor. Barnett has been premier since September 2008, making him the state’s fifth-longest-serving leader. He has seen five prime ministers come, and four prime ministers go. He trails Labor leader Mark McGowan in the “preferred premier” polls and shares with many leaders the problem of being perceived as “arrogant.” Certainly he has no claims to be populist, but his supporters see him as a strong leader.

The reality is that, aged sixty-six years, he would have preferred to hand over the leadership twelve months ago. But by then the obvious successors had disappeared. Christian Porter, who had served as treasurer and attorney-general, jumped ship into the federal arena and is now social services minister. The accident-prone Troy Buswell, another treasurer, committed one indiscretion too many and quit politics. Barnett was left with no obvious heir.

The second factor is the impact of WA’s roller-coaster economy on state finances. Barnett, a trained economist, initially boasted that he would never preside over a budget deficit. That was back in the days of billion-dollar surpluses. This year the budget deficit is tipped to be north of $3 billion, with state debt pushing beyond $30 billion. Debt was just over one-tenth of that amount when he took over in 2008.

In fairness to the premier, his term has coincided with a slump in royalty revenue following the crash in world prices for resources, as well as the collapse in the state’s returns from the goods and services tax. The latter will cost Western Australia about $3.5 billion this year compared to the amount it would receive if the GST pool were redistributed on a population basis. Regardless of the merits of the Commonwealth Grants Commission’s formula for spreading GST proceeds, that amount would leave a big hole in any budget.

By comparison, Mark McGowan has been a steady hand on the Labor tiller since gaining the leadership in January 2012. He was a minister in the last Labor government and oversaw the approval of Barrow Island as the base for the massive Gorgon LNG project, as well as the successful introduction of small wine bars in the state.

A naval lawyer before entering politics, the forty-nine-year-old McGowan survived an audacious challenge to his leadership from former foreign affairs minister Stephen Smith early last year. Although he isn’t in parliament, Smith offered himself as an alternative leader with the vision to take the party into government. Put to the test, his supporters vanished and the challenge evaporated, but not before McGowan’s leadership got up a fresh head of steam.

With unemployment nudging 7 per cent – the highest level for years – the economy, the state’s finances and jobs are key election issues. “An economy in transition” has been the government’s mantra for the past twelve months as it seeks to find new employment opportunities. Barnett has taken over the tourism portfolio and promoted the potential for more jobs throughout the state.

Labor has produced a comprehensive jobs policy that also includes a boost for tourism. But this comes with a questionable pledge to revive the manufacturing sector, including a promise to restore the state’s rail-car industry to provide rolling stock for a planned $2 billion–plus expansion of the suburban rail system.

The government damned the policy – “a nice idea” – with faint praise, adding that a major export market would be needed to guarantee efficiencies. McGowan responded by stating that Western Australia buys carriages made in Victoria and Queensland, and if those states can do it then so can Western Australia.

Privatisation is also shaping as a key issue. The Liberals are keen to push through the sale of several publicly owned assets, including a partial privatisation of Western Power – the poles and wires – estimated to raise a potential $11 billion. The Liberals would use the bulk of this money to retire debt and the rest for infrastructure. The TAB is also likely to go on the market if the Liberals have their way.

An issue infuriating environmentalists is the Perth Freight Link, designed to improve the connection of the Roe Highway to the port of Fremantle. Strong protests have been aroused by the fact that, when complete, it will run through part of a wetlands region.

National Party leader Brendon Grylls, meanwhile, has attracted the ire of mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton over his plan to increase the charge for extracting iron ore from 25c per tonne, which was set in the 1960s, to $5. He says the revenue would go a long way to solving the government’s budget problems. But he has received no support from the other parties, and the mining lobby has unleashed a ferocious $2 million advertising campaign claiming that the policy, if implemented, would make the industry less competitive and cost thousands of jobs.

Grylls is fighting for his political life in the seat of Pilbara, in the heart of iron ore country. But he is also aiming to head off the assault on the regional vote by One Nation, which polled 55,000 of the state’s Senate votes last year without really trying. Now the party is planning a major assault in the state poll, and support – especially in regional areas – is growing.

That’s why the Liberals have controversially agreed to preference One Nation ahead of the Nationals candidates in three non-metropolitan upper house regions, in return for One Nation preferences in the Legislative Assembly. That’s in stark contrast to the 2001 election, when the Liberals placed One Nation candidates last. (One Nation reciprocated by placing most sitting members last, and Labor won.)

The Liberals-One Nation preference deal has drawn strong criticism, especially from Labor and the Greens. But growing support for One Nation could prove to be the surprise packet when the votes are counted. And if the Liberals can get enough One Nation preferences to get them over the line, its criticism they'd be happy to wear.

Labor must win ten seats this time, with a uniform swing of 10 per cent, to gain power. It’s a tall order, but in a dynamic political climate, anything is possible. •