The Sea, the Sea

By Iris Murdoch | Vintage | $12.95

TO COINCIDE with the recent exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum of British Design 1948–2012, Vintage Books asked seven of the featured designers to “rethink the cover art for a selection of the most unforgettable, ground-breaking and life-changing British novels of the last seven decades.” For many, this will be another chapter in the increasingly uplifting story of the marriage between publishing and design, a marriage that is now back on the upward curve following several decades of what seemed irreversible decline. Like radio after the introduction of television, or television after VHS, the conventional book – the book as physical object – will, having survived through a bit of a rough patch, recover and thrive in the face of the new technologies, harnessing those very technologies to reach new readers and retain old ones. For those who support this version of recent history, the defining moment came a year ago, at the end of Julian Barnes’s speech accepting the 2011 Man Booker Prize for his novel The Sense of an Ending, in which he acknowledged the role of the book’s designer, Suzanne Dean, in his success. A book, he said, has to be more than the words on the page or on the screen. It “has to look like something worth buying and worth keeping.”

For others, the new technologies have already won; the current renaissance in book design will be brief, a last flowering before the inevitable triumph of the e-book, a format which is already, according to some reports, outselling old-style hard copy. Only last month, Amazon launched the Kindle Paperwhite, offering a more “paper-like” – or better – reading experience and faster page-turning times. (How fast, when it comes to page-turning, is fast enough?) It may well be, though, that in the end these two views converge; that the e-book will indeed triumph, but only after it has mastered the capacity to mimic not just the look and feel of paper but the look and feel of the book as a designed object, an object to be kept and even on occasions displayed and admired, its appearance serving as a continuing reminder of the experience of reading it. In such a scenario, the role of the book designer, so recently revived and recognised anew, will not fade away again but will continue to be central to both a book’s initial impact and its long-term survival.

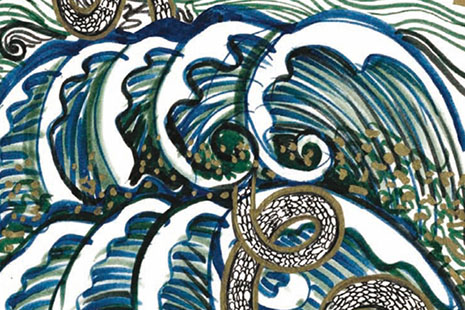

For this seven-volume set of “designer classics” Vintage commissioned work not from specialists in book design but from people who have made their creative reputations in other, related fields – advertising, architecture, interiors, textiles. Among them is the fashion designer Zandra Rhodes, now in her early seventies, who has been paired up with Iris Murdoch’s Booker Prize winner from 1978, The Sea, the Sea. Rhodes’s Hokusai-like cover, with its near-repeat pattern of crashing waves, echoes the repetitive structure of the novel, and the ways in which things, however much you try to escape them, will just keep on coming at you – in waves. (“Hokusai would love it,” says one of the novel’s more enigmatic characters, as he contemplates the boiling sea.) The would-be escapee is Charles Arrowby, a luminary of the theatre who chooses in his later years to leave worldly success behind and retire to a house by the sea, to think and write and cultivate detachment. Among the complex web of past relationships that preoccupy and in some cases pursue him, the novel increasingly focuses on his rediscovery of his lost, first love, a woman called Hartley Fitch.

In a novel that flaunts its use of improbable coincidence, the reappearance of Hartley in Charles Arrowby’s life – she’s living just down the road – is especially startling. Hartley, now in her sixties, is no longer the beautiful young girl with whom Charles was infatuated. Studying her with forensic care, he notes that “the eyes were thickly encased in wrinkles, the eyelids were brown and pitted as if stained, the cheeks were flabby,” only to conclude “how really unchanged that dear face was, and how little it mattered to my love that she was old.” Among the many, many things that this novel is about – some of them, such as the idea that we are all performers, acting our lives, have become, if anything, over-familiar as cultural themes – is the nature of old age, and what it means to reconcile the old self with the younger version, “to blend the present with the far past.” Charles Arrowby tries to recapture the past he remembers, going so far as to kidnap and imprison a reluctant and frightened Hartley, but he cannot direct real lives as he would a play, and must confront the fact that the past cannot be remade, or re-enacted in ways that change the ending.

In 1978, when The Sea, the Sea was first published, the e-revolution was just beginning. Murdoch herself wrote all her novels by hand, continuing to resist the lure of keyboard and screen. The characters in the novel communicate by letter; Charles Arrowby’s house is not connected to the telephone. Friends and acquaintances from the past are reunited by the boldness of the plot and Murdoch’s extravagant way with coincidence and not, as they would more plausibly be today, by means of an internet search or a reunion organised through Facebook. With its descriptions of forbidding rocks and dangerous waters, The Sea, the Sea has an almost pre-industrial air about it – shades of Gormenghast – and yet it strikingly anticipates a key dilemma of the digital age, the problem of how to deal with the increasing accessibility of our own pasts, and the tendency for those pasts to pop up unexpectedly. We need no longer rely on chance and coincidence to reintroduce us to our earlier selves. Technology will do it for us. To quote from another and more recent meditation on this theme, Jennifer Egan’s brilliant A Visit from the Goon Squad, which won the US National Book Critics Circle Award for 2010, “the days of losing touch are almost gone.”

In the face of all this connectedness, of the inescapability of our own autobiographies, The Sea, the Sea speaks up for the twin virtues of pressing on and letting go. Hartley’s husband Ben, who may or may not be a war hero and may or may not be abusive to his wife, puts it bluntly. “You don’t have to see people now because you saw them once or went to school with them or what.” As with all Murdoch’s fiction, it is of course rather more complicated than that. “How can old people be happy?” Charles recalls himself wondering as a youth. Perhaps by accepting that loose ends “can never be properly tied,” that “one is always producing new ones” and that, moreover, “time, like the sea, unties all knots.” Or perhaps by the traditional method of setting off for Australia, as Ben and Hartley do, in what reads like a parody of a new start. “Sydney harbour,” imagines Ben, “Sydney opera house, cheap wine, kangaroos, koala bears, the lot, I can’t wait.” Or perhaps, more realistically, by continuing to live and work and participate, without becoming overly preoccupied with opportunities missed and loves lost and paths not taken. Which makes Zandra Rhodes, still going strong, an even more appropriate choice as cover designer. •