Beyond Communal and Individual Ownership: Indigenous Land Reform in Australia

By Leon Terrill | Routledge | £95

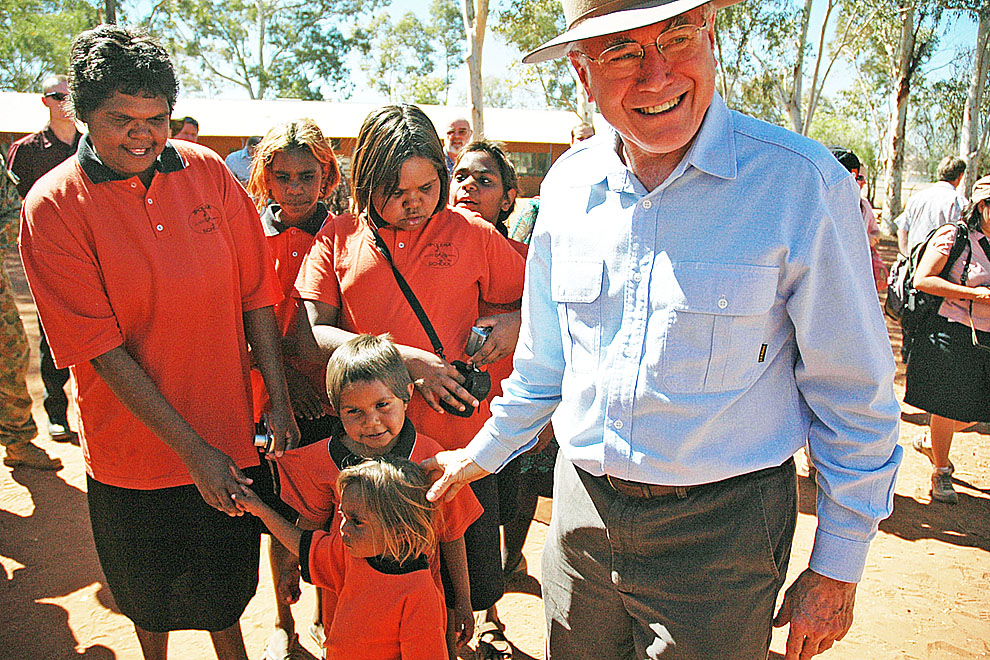

Indigenous land has been on the nation’s political agenda for the half-century since the Yolngu people failed in their bid to have their land rights recognised in late 1968. The first phase revolved around the subsequent Woodward royal commission and the enactment of statutory land rights schemes, initially in the Northern Territory. These reforms were driven by the Whitlam government, and particularly by the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, led by H.C. “Nugget” Coombs. That phase ended in 1985 when the Western Australian premier, Brian Burke, persuaded prime minister Bob Hawke to kill off the federal government’s proposed national land rights scheme.

The second phase, which can be interpreted as a direct judicial response to those decisions, was the legal revolution sparked by the High Court’s Mabo decision. At the core was the Native Title Act, which became law in 1993 and was amended in 1998, 2007 and 2009.

Leon Terrill’s excellent book provides the first comprehensive analysis of the third phase of national land rights policies. Here, the focus has shifted to changes in the management and use of Indigenous land through a process Terrill refers to as Indigenous land reform. Although he is primarily concerned with developments in the Northern Territory, he makes clear that the issues have national application and implications.

This third phase will inevitably spill over into policy debates about native title tenure and create pressure for further changes to the Native Title Act over coming decades. It involves three key components. First, the federal government introduced a “township leasing” system in NT Indigenous communities, under which government entities are granted head leases that they then sublease. Second, during the NT Emergency Response the federal government compulsorily acquired five-year leases over seventy-three “prescribed communities.” And third, under “secure tenure” policies introduced in Aboriginal communities across remote Australia, the federal government now requires community landowners to grant forty-year leases to relevant social housing authorities.

These reforms add up to an effort by government to formalise tenure and open up opportunities for greater economic development in remote communities. The implicit assumption driving these reforms – and often the explicit rhetoric – is that a lack of clear property rights, and the communal and inalienable nature of the rights that do exist, has impeded economic and commercial activity in these communities.

Terrill very usefully surveys the relevant international literature and the terms of the political and policy debate that presaged the policy changes. These chapters of Beyond Communal and Individual Ownership disentangle the complex theoretical literature and expertly unravel the threads pertinent to Indigenous Australian contexts.

Terrill is strongly and persuasively critical of the quality of the political debate about these issues, identifying the widespread use of loose language and concepts, and the substantial mismatch between the rhetoric justifying the reforms and the results to date. In particular, he argues that the focus on the binary choice between communal title and individual title has diverted the debate away from the issues that are most salient for remote communities.

This narrow and potentially unproductive framing reflects the fact that many conservatives use land tenure as a proxy for a much broader critique of Indigenous culture and worldviews. But a counter-reaction from the left of the political spectrum (which includes the two major NT land councils), which sees any potential change as threatening, has also contributed to the ideological polarisation.

Terrill also argues persuasively that the reforms have been poorly implemented. He sets up this argument with a chapter succinctly describing the institutional structures applying on Aboriginal land in the Northern Territory – primarily under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act – and a chapter outlining the social and micro-political relationships that permeate community life in remote townships and settlements.

These places are a mix of landowners with both customary and statutory rights, and occupiers/residents who only have informal rights based on accommodations reached over time with the landowners. (In a sense, these informal rights can be interpreted as an extension of traditional rights to forage or enter another person’s estate or country.) He also canvasses with approval the anthropological literature that sees these places, and the “Indigenous” organisations that operate within them, as occupying an “intercultural” space where every aspect of governance is framed according to the social/cultural location of the observer. Given these realities, government-initiated policy changes are inevitably open to resistance, reinterpretation and ultimately failure if they are handled insensitively.

Terrill outlines the elements of an alternative land reform policy. Rather than proposing a specific model of land reform, he opts for the safer approach of identifying the key principles any policy should adopt. He argues that it must recognise three “cardinal” issues: the nature of market conditions applying to the relevant communities, the desired model of governance sought in these locations, and the basis for benefit provision arising from or mediated through the planned structures.

These are highly abstract and implicitly value-laden concepts, and while they potentially provide an analytical framework they do not provide a road map or a guide to policy-making. With the nuts and bolts of policy-making inherently pragmatic and practical, “policy-making by template” would be bound to fail.

Terrill uses this framework to criticise the design elements of the land reforms undertaken to date. In particular, he argues that they have under-recognised the advantages of the pre-existing informal tenure arrangements. Significant social upheaval has arisen from the fact that the reforms prioritised landowners over occupiers and injected increased rent income into landowners’ pockets. As a consequence, the reforms have increased the risks of conflict between landowners and residents.

Terrill’s view is that land reform ought to ensure that the underlying land use authority in each location is structured to act in the interests of all community residents rather than just landowners, who often comprise a minority of residents and may actually reside elsewhere.

At the core of Beyond Communal and Individual Ownership are two chapters describing the recent reforms, outlining their genesis and operation, and assessing their performance, particularly in comparison to the political and policy rhetoric that preceded their implementation.

Importantly, Terrill links the various initiatives and demonstrates their common assumptions and elements, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the totality of the policy changes in this third phase of land rights. In particular, he expertly links the changes in legislation with the changes in housing policy. He also draws connections between the financial outcomes of land reform and government welfare policy, and the influential concern to counter welfare dependency.

This holistic analysis is especially important because the third phase of land reform is far from complete. Terrill’s analysis will assist immeasurably in understanding and shaping further land reform initiatives as they emerge over coming decades. For this reason alone, it is worth looking in more detail at some points of policy or political significance arising from his analysis.

The first key reform of the third phase, township leasing, is on the face of it a relatively minor reform, both in conception and implementation. As Terrill notes, it involves a new mechanism in section 19A of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act that was already implicit in section 19, albeit with specific lease terms and an executive director of township leasing to hold head leases and allocate subleases. The modesty of the reform is also reflected in the minimal take-up of the township leasing model, and the slow uptake of subleases by individuals and businesses within those townships.

Yet the new section has had a bigger impact than might have been expected. Terrill spends some time exploring how the head leases negotiated by government have been loaded up with constraints that run counter to the government’s rhetorical commitment that the subleases will be as close to freehold as possible. He also makes the point that the reforms have led to a much greater focus on the use of section 19 leases within remote communities on Aboriginal land, a development he doesn’t see as necessarily desirable. Nevertheless, the increasing formalisation of tenure across remote communities is the substantive and probably unintended consequence of the reforms.

This formalisation has occurred because the two major NT land councils have responded to the prospect of township leasing by aggressively pushing the use of standard section 19 leases, and because traditional owners have increasingly realised that informal tenures provide limited opportunities for recompense for the use of their land.

The second key reform, the compulsory acquisition of five-year leases over seventy-three prescribed communities as part of the NT Emergency Response, never had a well-articulated rationale. Its sole purpose appeared to be to pave the way for unconstrained access to communities by Commonwealth officials, particularly Australian Defence Force personnel (in the early phase of the Emergency Response) and government business managers.

Nevertheless, Terrill treats the acquisition of the leases as part of the broader land reform process and makes a number of critical comments about the legacy of these leases. There is a dearth of information about the motivations in play, but the proposal to take control of townships does align, albeit imperfectly, with the rhetoric about clearer property rights that has been so influential among conservative voices.

While it is clear that the “shock and awe” arrival of Australian Defence Force personnel and the combined force of the Emergency Response left deep and enduring scars on communities, these scars were not solely due to the five-year leases. Indeed the tangible changes in communities as a result of the leases were miniscule, and it was left to the federal Labor government to negotiate and pay the just terms compensation that was necessary to ensure the leases were a valid exercise of Commonwealth power.

The real significance of the compulsory acquisition is that it highlights the risks and complexity involved in pursuing policy reform on the run and acts as a warning of what an alternative model of land reform in the Northern Territory might have looked like. Had the Commonwealth decided to acquire the underlying freehold title and move to a freehold allocation approach, the narrative of continuing Indigenous dispossession would have been reinforced and confirmed, the cost to government would have been huge, immediate litigation would have been inevitable, and the broad approach to land reform in remote Australia would have been placed on a radically different footing.

The third land reform Terrill deals with is the so-called “secure tenure” change in the provision of remote housing, and its two components, home ownership and social housing provision. Terrill goes to some lengths to spell out the problematic history of government attempts to encourage home ownership in remote communities, and highlights the almost total failure of Coalition and Labor governments to make much progress. While home ownership ought to be available to all citizens (and in theory is available via long-term leases under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act), the reality is that the vast majority of remote residents are relatively poor and disadvantaged, and many are on welfare and/or do not have stable or secure jobs; many also have low levels of financial literacy, and have highly mobile lives that make living continuously in one location inconvenient.

Advocating home ownership as an unalloyed positive for any citizen, let alone disadvantaged Indigenous citizens, is problematic. Of course, the alternatives, social or community housing, also have their disadvantages, and there may well be different factors at play in locations like Cape York compared to the Northern Territory.

In relation to the reforms of social housing, Terrill makes a major contribution by spelling out the linkages between housing policy and land tenure. Of all the reforms implemented to date by government, the “secure tenure” reforms have had the most significant impact on the daily lives of Indigenous residents of remote communities. They have also been the most widespread, operating across all jurisdictions, and among the most contentious and difficult to implement, based as they are on governments effectively telling communities that they will not invest in new housing stock unless the communities (technically the landowners) agree to grant forty-year leases.

The context to these reforms included decades of underinvestment in remote housing by the state and territory governments, extremely high levels of overcrowding in virtually all remote communities, and extremely poor levels of repairs and maintenance. In 2008, these shortcomings led the Commonwealth to allocate $5.5 billion nationally over ten years under the National Partnership on Remote Indigenous Housing, an extraordinary surge in resources for remote housing. Of course, the political impetus was strongly shaped by the wider concerns about poor health, community dysfunction and welfare dependence that had led to the Emergency Response.

Terrill lays out a range of arguments critical of the social housing reforms: the term “secure tenure” is a misnomer and not consistent with accepted definitions; the policy intention has been “to implement a strategic reduction in tenure security for Aboriginal residents”; the scheme has imposed excessive conditions on tenants in tenancy agreements and removed the ability to transfer residency within families; and the consequence of all these changes has been to reduce the autonomy of residents. These changes are “inherently interventionist,” he correctly notes, “in that they deliberately impose a greater role for governments and a lesser role for community organisations.”

Terrill’s critique places most emphasis on the new responsibilities imposed on tenants, and under-emphasises the new landlord responsibilities imposed on government. Recent media coverage of poor or non-existent maintenance of community housing by Territory Housing suggests that the implementation of the reforms has left much to be desired, with over 600 outstanding maintenance issues being identified in one community alone. Yet it is crystal clear that government is now responsible for community housing and can be held legally accountable for its landlord obligations.

Beyond Communal and Individual Ownership provides the first comprehensive analysis and assessment of the third phase of Indigenous land rights. Leon Terrill has untangled what is, even for those with an interest in these issues, a tight knot of culture, history, demography, anthropology, federalism, bureaucracy, law and politics. It is a considerable achievement.

What emerges is that the structural and institutional forces at work in remote Australia – the laws, the key organisations, and the intricate interplay of interests shape and determine much more than is generally acknowledged. Moreover, the land reform process is still in flux. The directions of reform might be reasonably clear, but the details are not set in concrete and will be shaped for good or bad by the interplay of stakeholders and politics. The decisions reached will in many respects determine the shape of remote communities and the opportunities of their residents for decades to come.

Beyond Communal and Individual Ownership provides us with an entry point into that policy space, a vision of the policy alternatives that might be pursued in the future, and an analysis of the issues that will need to be addressed and determined whichever course is adopted. This is a very substantial achievement in itself.

Priced at £95, this book is clearly targeted at the research library market rather than individual purchasers. Nevertheless, it is essential reading for anyone who is keen to understand Indigenous land reform in recent years, and who wishes to think seriously about the direction of land rights and native title policies in Australia over the coming decades. •