In Alang, the centre of India’s ship-breaking industry, they deal with ships as big as 50,000 tonnes. The people who break them up for scrap are lonely men who usually come from eastern India, attracted by better wages than they would get at home — if there were any work for them there. They have no personal attachment to or cultural beliefs about the ships they take apart.

The contrast with another of India’s recycling enterprises — the one that deals with the tiniest of items, strands of human hair — is tantalising. When you break up a ship, the dismantled components acquire value. When you collect hair, it’s the combining of millions of individual strands into a new product that creates value. Collect enough hair and you can feed your family — or even, in rare cases, become a millionaire. Ship breaking brings the world’s waste to India; hair collecting carries India’s discards to the world.

One of us, Assa Doron, first encountered the hair business when he met a group of young boys scavenging for recyclables on the outskirts of Varanasi, in Uttar Pradesh. Carrying white polypropylene sacks full of stuff collected through the morning, the boys were happy to unload the day’s catch for inspection. At first glance, the contents looked like rubbish: disordered, moist and sordid. But as the British anthropologist Mary Douglas wrote, order is established by acts of elimination and discretion — by identifying items and judging their potential.

The boys sorted their collection on the muddy ground. They picked out strands of hair and separated them carefully from the rest of the refuse, which included a fluorescent-green flip-flops, empty henna bottles, a grey wristwatch, a green soda can, a white cassette tape, and various other items, all of which were put back into the bag. The clumps of hair were placed carefully into a plastic container, where they formed a substantial black mass. “We just pick it up along the way, anywhere, on the road and drains,” said one boy. “But what do you do with it?” Doron asked. The boys explained that they sold it to a nearby Bengali hair trader.

The boys lived in a slum that housed a community of poor migrants, mostly Muslims. Their huts were made of salvaged materials: gunnysacks and tarpaulins stitched together to form walls held in place by bamboo and metal poles. The roofs were a puzzle of corrugated iron and coloured plastic sheets weighed down with automobile tyres. Most of the inhabitants relied on waste work for income.

A few of the children described the scavenging routes they followed throughout the day. With specific rubbish heaps guarded as the prized territory of particular families, they tended to forage on larger, more formal rubbish sites near roadside bins. But this could be tricky because those sites were often under the jurisdiction of municipal cleaners (safai karmachari) who had first pick of whatever came to the site.

What was especially intriguing in this encounter in Varanasi was that the waste-pickers of this slum specialised in human hair. And it was everywhere. Bundles of it lay outside the huts, drying on plastic sheets. “The hair is washed and gathered until we have a large enough quantity, and then we sell it to Mr Khan,” explained one of the boys. Water was essential for cleaning the hair, and this community, unlike others, had ready access. Throughout the day, women and children armed with buckets waited their turn at a well.

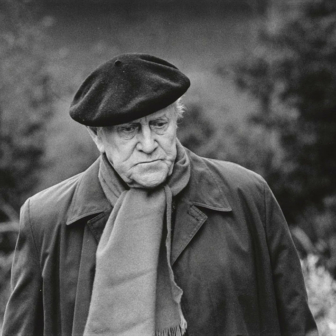

Mr Khan was a specialist, a necessary link in any chain that processes waste to give it new value. His humble office was across an alley opposite the slum, located in a small compound that served migrant rickshaw pullers from Bihar. During Doron’s visit a boy brought in a bag of hair to be weighed on large mechanical scales hanging from the ceiling. He was given ₹600 (about A$12) for 500 grams. The quick transaction represented the fruits of a few weeks of collecting.

The wad of hair was then added to one of the large gunnysacks lying against the wall, each stuffed with hair. Mr Khan described this as black, kaccha hair — raw hair. It fetched a better price than grey hair from the elderly, which he called pakka, or matured, hair. The most prized bags contained women’s long black hair, probably shaved for ritual purposes. Varanasi is a leading pilgrimage centre, and head-shaving rituals commonly mark key milestones of life.

The anthropologist Emma Tarlo examines the global hair industry in her fascinating book Entanglement. As she shows, the temples of southern India are famous for the pristine hair collected when pilgrims shave their heads there before worship. Although it is commonly known as temple hair, in professional circles it is called remi, or virgin, hair and is regarded as the purest in quality. This black gold sustains a multimillion-dollar global industry of wigs and hair extensions.

Indian women’s hair is coveted because it is usually unadulterated by dyeing, bleaching or streaking, and temple hair enjoys its reputation because much of it comes from devout rural women who have carefully groomed and oiled their hair for decades. Tarlo traces the commodity chain — whether it’s comb waste or temple tresses — as it travels along unanticipated routes, from Myanmarese hair-processing villages to Chinese factories to an international hair expo in Jackson, Mississippi. Entangled in social and cultural meaning, the global hair trade is anything but straightforward.

The specialist: weighing and bagging waste hair in Varanasi, 2015. © Assa Doron

Human hair has long been an object of fascination and reverence in India. For Hindus especially, writes researcher Eiluned Edwards, “the removal of hair is seen as an act of purification and, at a metaphysical level, represents the abandonment of ego (ahamkara), the extinction of individuality, which is a prerequisite of achieving the soul’s release, nirvana, or ‘perfect bliss.’”

Hair figures in various life-cycle rituals and pilgrimage rites. Hindus mostly speak of pilgrimage and sacrifice as a form of gratitude to God for granting good fortune, health or economic success. At Tirupati, the most famous pilgrimage centre in south India, thousands of pilgrims line up every day to have their heads shaved in purpose-built tonsuring halls, where barbers employed by the temple authorities do nothing but shave heads. Once shaved, pilgrims go to receive the blessing of the Tirupati deity.

Temple employees collect, clean and store the hair until it is auctioned to dozens of dealers eager to bid for premium material. At one auction in 2016, the Tirupati authorities reported a return of ₹50.7 million (about A$1 million). A year earlier, the starting bid for “first variety” hair, which is black and eighty centimetres or longer, was ₹25,500 (about A$505) a kilogram. The temple had only 1.3 tonnes of “first variety” to auction, but it had 194 tonnes of “fifth variety,” less than five inches long, with an opening-bid requirement of a mere ₹35 (about 70c) a kilogram.

This was a far cry from Mr Khan’s venture in Varanasi. The majority of the hair that came to him had been collected by scavengers. If he was lucky, he occasionally received high-quality long hair, usually from widows who shaved their heads to mark their new social status after seeking refuge in this sacred city. “This kind of lengthy hair,” Mr Khan explained, “could fetch up to ₹1500 per kilogram — but it is rare to get.” Most of the hair came from pavement barbers and the daily brushing of women; but another source, he added, was the countryside, where roving traders (pheriwalas) collected strands of hair that village women gathered from their combs and brushes.

So far, Doron had found four broad groups of participants in the chain that captures and gives new value to thrown-away things. There were the small boys who first caught his eye in Varanasi. They were connected indirectly to the women who discarded strands of hair. There were the pheriwalas, the travelling traders who collect hair on their rounds of small towns and villages, and there was Mr Khan, who aggregated what had been collected. In south India, there were the great temples, devotees, barbers and the authorities who organised the auctions. But to find out what happened after hair left Mr Khan’s premises, Doron was directed to Delhi.

There, on the top floor of a nondescript building near Paschim Vihar metro station, was Mr Ashok’s export business. Several women worked in a large room processing hair, some using large purpose-built combs called hackles to refine and measure it. Others packed bundles of hair. A couple of men worked on sewing machines that stitched wefts (loose hair sewn together to make a lock of hair). Outside, on a small verandah, black hair soaked in buckets of chemicals and treated hair dried on the balcony.

The adjacent room functioned as the front office, from where Mr Ashok, his wife and his brother conducted the business. The room had a large desk and brown leather sofas and was decorated with specimens of hair hanging on the walls — Brazilian, curly, raw, single, double-drawn and coloured. Everything was neat and clean.

Mr Ashok was the son of a farmer in a village near Agra. Like many of his generation, he found little appeal in following his father’s occupation. He completed vocational training at Ambedkar University and, in 2011, a master’s degree in business administration from Galgotia University on the outskirts of New Delhi. “I then began working in B2B [business to business],” he said, “in a job in sales as a marketing manager for three years. This way I could repay my [university] debt.”

The chain continues: a small-scale hair processing factory in New Delhi, 2015. © Assa Doron

Another dealer of comparable size but longer standing to Mr Ashok is Mr Sonu, whose trajectory illustrates the deep roots of waste traders. His grandfather, a Khatiik farmer from Haryana, came to the hair trade by chance in the 1970s. Most of the hair he procured ended up in Mumbai, intended for wigs and the entertainment business. Poor-quality hair was sold for stuffing mattresses. But Mr Sonu had bigger ideas for the business and looked beyond the domestic market. After some extensive web-based research, he decided to travel to Brazil, his first-ever overseas trip.

His parents disapproved of his frivolous adventure. “Why go to Brazil? Business is just here,” they told him. Eventually, he convinced them and set off for Brazil with a new passport and bundles of waste hair in a couple of suitcases. “It was amazing how fast I managed to sell the hair,” he said, “and the money covered my flight tickets and accommodation, and I even had some money left; I could not believe it.”

Mr Sonu began to travel regularly to Brazil, carrying suitcases full of hair. But smuggling hair in this way had its limits, as he discovered during the soccer World Cup of 2014. Airport security was beefed up, and the kilograms of hair in his luggage were confiscated. “That’s when I realised I must do things differently.”

Over the next few months he acquired the right documentation and licences and “lubricated the right people, otherwise nothing gets done here.” In 2015, he exported between fifty and one hundred kilograms a month to his Brazilian partner. “Business is getting better every day,” he said as he showed off recent text messages from clients in France, Angola and Spain. “Next month I am off to Norway. Have you been there?”

The hair trade earned its moment in the national limelight in 2015 when the president of India presented an award from the Federation of Indian Export Organisations to the self-styled king of waste hair for his company’s stellar export performance. A pioneer of the industry, D.C. Solanki claimed to be exporting an astonishing sixty tonnes of waste hair a month. “Last year,” he said, “my business was named the top export business in India. We are the largest traders in raw waste hair in India, which is used for wigs, hair extensions and many different products.”

A wall-size poster of India’s president with Mr Solanki and his family adorns the entrance to the company’s factory in north Delhi. “I don’t deal with temple hair, it’s too expensive; here we only use waste hair,” Mr Solanki said. “I have lakhs [hundreds of thousands] of workers all over India.” He was referring to the armies of freelance waste-pickers whose collections reached his factory through a chain of middlemen like Mr Khan in Varanasi.

The Solanki factory spans a whole block. At one end, a roofed bay contains hundreds of large polypropylene bags stuffed with hair. Once unpacked, the hair is processed in several large halls. The sacks of hair are piled at one end; brown boxes, ready for export, are stacked at the other. Workers comb, cut, measure, classify and weigh bundles of hair before packing and loading them onto trucks, destined mainly for China, Africa and Europe. The factory floor is a typical production line, but instead of producing automobiles or grading apples, workers use specialised tools to ensure quality and uniformity.

The colour code: hair being sized and packed in New Delhi, 2015. © Assa Doron

The male employees were dressed in dhotis and colour-coded t-shirts (yellow, orange and pink) that indicated their role in the factory. The yellow shirts operated in a hall that housed dozens of large plastic crates piled high with waste hair. Young men sat cross-legged on the concrete floor, combing the product on machines that looked like miniature fakir beds — long rectangular planks of wood fitted with nails pointing up. These were designed for refining large bundles of hair, after which it was measured for length and quality. The now-smooth hair was then divided into small, silky bundles, wrapped with different coloured ribbons, and placed in one of the plastic crates according to its grade and length.

This repetitive work continued in another large hall. The classified and colour-coded hair was measured again, trimmed to size and gently laid in cardboard boxes. Like glassware, luxurious hair has to be handled with care. The boxes were weighed and an information slip placed on top, noting the amount, type and length of hair. Once sealed, the boxes were moved to another large hall before being loaded onto trucks.

The trucks that took Mr Solanki’s processed hair to the airport might appear to be the end of the waste-transforming chain. The waste hair was purged of its former life, transformed into a commodity and subjected to the forces of the market. But hair is a commodity in a global market, and so it is subject — as are other recycled objects — to further surprises in the form of unexpected price fluctuations. In 2004, for instance, the hair industry received a setback as a result of the actions of a Jewish community in Brooklyn, New York.

In many Orthodox Jewish communities, women must cover their hair after marriage as a mark of modesty (tzniut). They wear head coverings (sheitel) such as hats, scarves or wigs. Wigs have become increasingly fashionable among Orthodox women, some investing thousands of dollars in wigs made of human hair. Often it is the best quality in the market — Indian hair. But in 2004, an Israeli rabbi who discovered that most human-hair wigs came from Indian temples deemed such wigs to be idolatrous and issued a ban. As the New York Times’s Daniel Wakin reported:

Synthetic wigs flew off the shelves yesterday at Yaffa’s Quality Wigs in the Borough Park section of Brooklyn. On the crowded streets of the neighbourhood, an increasing number of Orthodox Jewish women were seen wearing cloth head coverings, having left their wigs at home. Sarah Klein, a neighbourhood resident, said that until the confusion was cleared up, she would leave the house only if she wore a baglike snood.

As Emma Tarlo observes, the tainted wigs were seen as too vile and dangerous for anything other than destruction by fire. Orthodox Jewish women largely stopped wearing wigs made of Indian temple hair, and the Indian hair industry had to adjust to the shock of losing a section of its market.

This globalisation story is instructive in two ways. The most obvious is the complexity of the global chain of recycling. The boundaries between the informal and formal sector are blurred, entwined and interdependent. Strands of hair like those that first attracted Doron’s attention when he saw the boys pulling them out of the gutter in Varanasi can cause a minor religious panic in New York City, which in turn causes a temporary collapse in the demand for waste hair in the back lanes of north India.

These stories also highlight the less obvious qualities that inhere in waste and recycling. Material things have histories arising from everyday personal rituals as simple as combing hair. Waste can become highly symbolic and produce strong reactions, and even discarded hair can acquire abstract qualities. ●

This is an edited extract from Waste of a Nation: Garbage and Growth in India, published this month by Harvard University Press.